Changing the Game: Title IX, Gender and Athletics in American Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

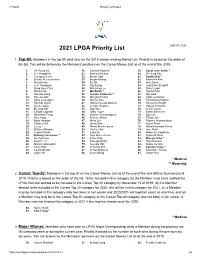

2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021

1/7/2021 Priority List Report 2021 LPGA Priority List JAN-07-2021 1. Top-80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the 2019 season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the 2019. 1. Jin Young Ko 30. Caroline Masson 59. Sarah Jane Smith ** 2. Sei Young Kim 31. Azahara Munoz 60. Wei-Ling Hsu 3. Jeongeun Lee6 32. Bronte Law 61. Sandra Gal * 4. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Megan Khang 62. Katherine Kirk 5. Nelly Korda 34. Su Oh 63. Amy Olson 6. Lexi Thompson 35. Ally Ewing 64. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 7. Sung Hyun Park 36. Mi Hyang Lee 65. Stacy Lewis 8. Minjee Lee 37. Mo Martin * 66. Gerina Piller 9. Danielle Kang 38. Suzann Pettersen ** 67. Mel Reid 10. Hyo Joo Kim 39. Morgan Pressel 68. Cydney Clanton 11. Ariya Jutanugarn 40. Marina Alex 69. Pornanong Phatlum 12. Hannah Green 41. Nanna Koerstz Madsen 70. Cheyenne Knight 13. Lizette Salas 42. Jennifer Kupcho 71. Sakura Yokomine 14. Mi Jung Hur 43. Jing Yan 72. In Gee Chun 15. Carlota Ciganda 44. Gaby Lopez 73. Sarah Schmelzel 16. Shanshan Feng 45. Jasmine Suwannapura 74. Xiyu Lin 17. Amy Yang 46. Kristen Gillman 75. Tiffany Joh 18. Nasa Hataoka 47. Mirim Lee 76. Pajaree Anannarukarn 19. Charley Hull 48. Jenny Shin 77. Austin Ernst 20. Yu Liu 49. Nicole Broch Larsen 78. Maria Fernanda Torres 21. Brittany Altomare 50. Chella Choi 79. -

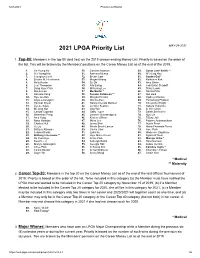

2021 LPGA Priority List MAY-24-2021

5/24/2021 Priority List Report 2021 LPGA Priority List MAY-24-2021 1. Top-80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the 2019 season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the 2019. 1. Jin Young Ko 30. Caroline Masson 59. Sarah Jane Smith ** 2. Sei Young Kim 31. Azahara Munoz 60. Wei-Ling Hsu 3. Jeongeun Lee6 32. Bronte Law 61. Sandra Gal * 4. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Megan Khang 62. Katherine Kirk 5. Nelly Korda 34. Su Oh 63. Amy Olson 6. Lexi Thompson 35. Ally Ewing 64. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 7. Sung Hyun Park 36. Mi Hyang Lee 65. Stacy Lewis 8. Minjee Lee 37. Mo Martin * 66. Gerina Piller 9. Danielle Kang 38. Suzann Pettersen ** 67. Mel Reid 10. Hyo Joo Kim 39. Morgan Pressel 68. Cydney Clanton 11. Ariya Jutanugarn 40. Marina Alex 69. Pornanong Phatlum 12. Hannah Green 41. Nanna Koerstz Madsen 70. Cheyenne Knight 13. Lizette Salas 42. Jennifer Kupcho 71. Sakura Yokomine 14. Mi Jung Hur 43. Jing Yan 72. In Gee Chun 15. Carlota Ciganda 44. Gaby Lopez 73. Sarah Schmelzel 16. Shanshan Feng 45. Jasmine Suwannapura 74. Xiyu Lin 17. Amy Yang 46. Kristen Gillman 75. Tiffany Joh 18. Nasa Hataoka 47. Mirim Lee 76. Pajaree Anannarukarn 19. Charley Hull 48. Jenny Shin 77. Austin Ernst 20. Yu Liu 49. Nicole Broch Larsen 78. Maria Fernanda Torres 21. Brittany Altomare 50. Chella Choi 79. -

Women in Golf

WOMEN IN GOLF T HE P LAYERS, THE H ISTORY, AND THE F UTURE OF THE SPORT DAVID L. HUDSON,JR . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hudson, David L., 1969– Women in golf : the players, the history, and the future of the sport / David L. Hudson, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–275–99784–7 (alk. paper) 1. Golf for women—United States. 2. Women golfers—United States—Biography 3. Sex discrimination in sports—United States. 4. Ladies Professional Golf Association. I. Title. GV966.H83 2008 796.3520922—dc22 2007030424 [B] British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by David L. Hudson, Jr. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007030424 ISBN: 978–0–275–99784–7 First published in 2008 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48-1984). 10987654321 To the memory of my beloved grandmother, Rose Kostadin Krusa, who loved the great game of golf with all of her beautiful soul and spirit. C ONTENTS Acknowledgments ix 1. Golf’s Origins 1 2. Early Greats of the Game 9 3. Joyce Wethered—The Greatest Female Golfer Ever 19 4. The Babe and the Berg...and Louise Suggs 29 5. -

Swinging Around Golf

The Agavvam Hunt club recently hon- ored pro Fred Dinger at a testimonial banquet for his 40 years of service . Tom Maries, former pro at Lake Forest, Hudson, O., is now at Tippecanoe CC, Canfield,. Ohio ... The Clear View public course (near Myrtle Creek, Ore.) opened its newly built nine April 10 . A. F. (Bud) Nash designed Scothurst CC, Lumber Bridge, N. C., which will open its 18 this summer. Kirby Bowman, a Siloam, N. C. farmer, is developing a 9-hole course on his farm . May 1 is the opening of the Par-3 course constructed by Bob Coppock, Yucca Valley, Calif. Bill Byers now supt. of the Des Moines (la.) G&CC . A new and large addition is being made to the clubhouse of the Traer, (la.) GC. SWINGING Rifle (Colo.) Creek GC has added a new cocktail lounge, a storage room for AROUND personal belongings and golf carts, plus a storage area for electric cars, according GOLF to Mr. and Mrs. Jim LeDonne, managers . Sherwood Development Co. has plans for an 18-hole course and 1,220 homes News of the Golf at the Twin Lakes CC about six miles from downtown Tacoma, Wash. Build- World in Brief er and designer is A1 Smith . Smith also designed two courses now under con- By HERB GRAFFIS struction in the Bellevue, Wash, area, Brae Burn and Tam O'Shanter. A deep-drilled well will furnish water for the Twenty-nine Palms (Calif.) GC and home sites that are being developed . Bill Zimmerebner, pro, at Burns Park Front Cover municipal course, says that the North Little Rock, Ark. -

Lynn Adams 1 1983 Kathy Ahern 3 1972 Shi Hyun Ahn 1 2003

Lynn Adams 1 1983 Kathy Ahern 3 1972 Shi Hyun Ahn 1 2003 South Korea Kristi Albers 1 1993 Amy Alcott 29 1991 Helen Alfredsson 5 2003 Sweden Danielle Ammaccapane 7 1998 Janet Anderson 1 1982 Donna Andrews 6 1998 Jody (Rosenthal) Anschutz 2 1987 Debbie Austin 7 1981 Marisa Baena 1 2005 Colombia Pam Barnett 1 1971 Sharon Barrett 1 1984 Tina Barrett 1 1989 Barbara Barrow 1 1980 Patty Berg 60 1962 Susie (Maxwell) Berning 11 1976 Missie Berteotti 1 1993 Silvia Bertolaccini 4 1984 Argentina Jane Blalock 27 1985 Jocelyne Bourassa 1 1973 Canada Nanci Bowen 1 1995 Pat Bradley 31 1995 Murle (Lindstrom) Breer 4 1969 Jerilyn Britz 2 1980 Vivian Brownlee 1 1977 Bonnie Bryant 1 1974 Barb (Bunkowsky) Bunkowsky-Scherbak 1 1984 Canada Betty Burfeindt 4 1976 Brandie Burton 5 1998 Carole Jo (Skala) Callison-Whitted 4 1974 Donna Caponi 24 1981 JoAnne Carner 43 1985 Nicole Castrale 1 2007 Silvia Cavalleri 1 2007 Italy Mei-Chi Cheng 1 1988 Taiwan Dawn (Coe) Coe-Jones 3 1995 Canada Janet Coles 2 1983 Maria (Astrologes) Combs 1 1975 Kathy Cornelius 6 1973 Jane Crafter 1 1990 Australia Paula Creamer 4 2007 Clifford Ann Creed 11 1967 Fay Crocker 11 1960 Uruguay Mary Lou Crocker 1 1973 Elaine Crosby 2 1994 Betsy Cullen 3 1975 Heather Daly-Donofrio 2 2004 Beth Daniel 33 2003 Laura Davies 20 2001 England Dorothy Delasin 4 2003 Florence Descampe 1 1992 Belgium Laura Diaz 2 2002 Judy (Clark) Dickinson 4 1992 Helen Dobson 1 1993 England Betty Dodd 2 1957 Wendy Doolan 3 2004 Australia Dana (Lofland) Dormann 2 1993 Moira Dunn 1 2004 Dale (Lundquist) Eggeling 3 1998 Gloria -

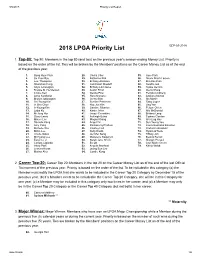

2018 LPGA Priority List SEP-05-2018

9/5/2018 Priority List Report 2018 LPGA Priority List SEP-05-2018 1. Top-80: Top 80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the previous year's season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the previous year. 1. Sung Hyun Park 28. Chella Choi 55. Jane Park 2. So Yeon Ryu 29. Katherine Kirk 56. Nicole Broch Larsen 3. Lexi Thompson 30. Brittany Altomare 57. Kim Kaufman 4. Shanshan Feng 31. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 58. Sandra Gal 5. Ariya Jutanugarn 32. Brittany Lincicome 59. Ayako Uehara 6. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Austin Ernst 60. Alena Sharp 7. Cristie Kerr 34. Gerina Piller 61. Pernilla Lindberg 8. Anna Nordqvist 35. Haru Nomura 62. Azahara Munoz 9. Moriya Jutanugarn 36. Jenny Shin 63. Mo Martin 10. Sei Young Kim 37. Suzann Pettersen 64. Gaby Lopez 11. In Gee Chun 38. Hyo Joo Kim 65. Jing Yan 12. In-Kyung Kim 39. Caroline Masson 66. Peiyun Chien 13. Lydia Ko 40. Karine Icher 67. Ally McDonald 14. Mi Jung Hur 41. Jacqui Concolino 68. Brittany Lang 15. Stacy Lewis 42. Ashleigh Buhai 69. Cydney Clanton 16. Minjee Lee 43. Megan Khang 70. Wei-Ling Hsu 17. Danielle Kang 44. Angel Yin 71. Sun Young Yoo 18. Amy Yang 45. Pornanong Phatlum 72. Laura Gonzalez Escallon 19. Michelle Wie 46. Charley Hull 73. Olafia Kristinsdottir 20. Mirim Lee 47. Nelly Korda 74. Ryann O'Toole 21. Lizette Salas 48. -

India in Complete Control of Three Portuguese Enclaves

-I LOW T~DE 12/20 0 7 AT 2u44 12/21 0 7 AT 0932 VOlo 3 No. 998 KWAJALEIN, MARSHALL ISLANDS WEDNESDAY 20 DECEMBER ~96~ FIGHTING ~TOFPfO I~ CONGO INDIA IN COMPLETE CONTROL OF CI TV; TSHOlvlBE OFF TG ~(d:' TI NG THREE PORTUGUESE ENCLAVES vV ITH CfNTRAL, GOV 8 T PRF]1! [R BtlGAUM, ~NDIA, DEC. 19 {UPI )-INDIAN TROOPS OVERWHELMED 16,000 PORTUGUESE NDOlA, NORTHERN RHODESiA, DECo i9 lROOPS ENTRENCHED IN THE Go AN CAPITAL Of PANGIM IN A fiERCE BATTLE EARLY TO (UPI )-KATANGA PRESIDENT Mo'sE TSHOMBE DAY AND THE MllL!TARY COMMANDER Of GOA SURRENDERED, THE INDIAN ARMY ANNOUNCED. fLEW Off TO KITONA WITH U.S. AMBASSADOR THE ACT'O~ MEANT THAT INDIA WAS IN COMPLETE CONTROL Of PORTUGAL'S THREE EDMUND A. GULLION TODAY fOR A CONfER ENCLAVES !N LiTTLE MORE THAN 24 HOURS AfTER LAUNCHING ITS INVASIONS. ENCE WITH CONGO CENTRAL GOVERNMENT ThE CAPTURE Of PANGIM HAD BEEN EXPECTED AT ANYTIME SINCE LAST MIDNIGHT, BUT PREMIER CYRILLE AOOULA. 1HE 'ND~ANS SA!D THEY DELAYED THEIR OffENSIVE BECAUSE THEY fEARED THERE WOULD THE MEETING WAS BROUGHT ABOUT THROUGH BE HEA~Y CIVILIAN CASUALTIES If THEY ATTACKED IMMEDIATELY. A MASSIVE UNITED NATIONS ATTACK O~ INDIAN OfFICIALS SAID THERE WAS hVERY HEAVY fiGHTING" AfTER DAWN BUT THE TSHOMBE'S fORCES IN ELiSABETHV~lLE PORTUGUESE LAiD DOWN THEIR ARMS AfTER A fiNAL, 50-MINUTE MORTAR BARRAGE. AND PRESIDENT KENNEDY'S EfrO~TS TO (PORTUGUESE REFUGEES WHO ARRIVED IN KARACHI, PAKISTAN, fROM GOA TODAY TOLD RESOLVE THE CONGOYS TURMOil. A ~ARRO_!NG TALE Of AN AIR ESCAPE DURING AN INDIAN ARTILLERY ATTACK AND A NIGHT ~T COULD PROVIDE A DRAMAT!C BR£A~~ Fk~GH~ FROM PANGiM WITHOUT LIGHTS TO AVOID INTERCEPTION. -

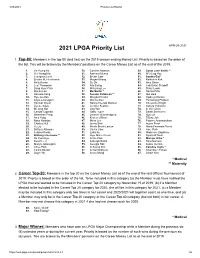

2021 LPGA Priority List APR-26-2021

4/26/2021 Priority List Report 2021 LPGA Priority List APR-26-2021 1. Top-80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the 2019 season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the 2019. 1. Jin Young Ko 30. Caroline Masson 59. Sarah Jane Smith ** 2. Sei Young Kim 31. Azahara Munoz 60. Wei-Ling Hsu 3. Jeongeun Lee6 32. Bronte Law 61. Sandra Gal * 4. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Megan Khang 62. Katherine Kirk 5. Nelly Korda 34. Su Oh 63. Amy Olson 6. Lexi Thompson 35. Ally Ewing 64. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 7. Sung Hyun Park 36. Mi Hyang Lee 65. Stacy Lewis 8. Minjee Lee 37. Mo Martin * 66. Gerina Piller 9. Danielle Kang 38. Suzann Pettersen ** 67. Mel Reid 10. Hyo Joo Kim 39. Morgan Pressel 68. Cydney Clanton 11. Ariya Jutanugarn 40. Marina Alex 69. Pornanong Phatlum 12. Hannah Green 41. Nanna Koerstz Madsen 70. Cheyenne Knight 13. Lizette Salas 42. Jennifer Kupcho 71. Sakura Yokomine 14. Mi Jung Hur 43. Jing Yan 72. In Gee Chun 15. Carlota Ciganda 44. Gaby Lopez 73. Sarah Schmelzel 16. Shanshan Feng 45. Jasmine Suwannapura 74. Xiyu Lin 17. Amy Yang 46. Kristen Gillman 75. Tiffany Joh 18. Nasa Hataoka 47. Mirim Lee 76. Pajaree Anannarukarn 19. Charley Hull 48. Jenny Shin 77. Austin Ernst 20. Yu Liu 49. Nicole Broch Larsen 78. Maria Fernanda Torres 21. Brittany Altomare 50. Chella Choi 79. -

U.S. Women's Open 1

U.S. Women’s Open 1 U.S. Women’s Open Championship Record Book 2020 2 U.S. Women’s Open Jeongeun Lee6 Wins the 2019 Championship Jeongeun Lee6 of the Republic of Korea broke out of a pion So Yeon Ryu finished tied for second place, two strokes crowded leader board with three back-nine birdies and with- back at 4-under 280, while Boutier was in a group of five stood some late struggles to shoot 1-under-par 70 and win players at 3-under 281. the 74th U.S. Women’s Open Championship by two strokes over a trio of players at the Country Club of Charleston. Lee6’s final round of 70 was her eighth under-par effort in 12 career U.S. Women’s Open rounds. Lee6 finished fifth in her Lee6, who turned 23 during championship week, earned $1 championship debut in 2017 at Trump Bedminster and tied for million in notching her first victory in the United States. The 17th last year at Shoal Creek. six-time winner in three seasons on the Korea LPGA Tour, who is in her first full-time season on the LPGA Tour, shot 70-69- Her victory marked the 18th victory in the last 36 major 69-70 for a 6-under-par total of 278. championships for players from the Republic of Korea, and she is also the 11th different player in 11 years to win the U.S. “She couldn’t imagine coming this far,” said Jennifer Kim, Women’s Open and the ninth different player to win a major Lee6’s manager and translator. -

Tournament Records

Table of Contents Welcome from CP . 2 Celebrating the CP Women’s Open . 3 Contacts . 4 Tournament Fact Sheet . 5 Daily Schedule . 6 Television Broadcast Schedule . 7 Tournament Yardage and Par . 8 Total Purse . 9 About Magna Golf Club . 10 Course Fact Sheet . 11 CP Has Heart: SickKids Foundation/Southlake Regional Health . 12-15 Tournament Results (since 1966) . 16-66 Summary of Winners . 67 Best Canadian Performances . 68 Leading Canadian Money Winners . 69-70 Daily Low Scores . 71-73 Tournament Records . 74-75 1 2019 CP Women’s Open Welcome to the 2019 Canadian Pacific Women’s Open I’m pleased to welcome contenders and fans to the 2019 CP Women’s Open at the world-renowned, Magna Golf Club in Aurora, Ont . CP is very proud to celebrate the 6th year as the title sponsor of Canada’s National Women’s Open Golf Championship . The CP Women’s Open continues to attract elite players from around the world, and this year is no exception . We’re thrilled to support our two tournament ambassadors, 2016 Canadian Golf Hall of Famer Lorie Kane and Major LPGA Champion Brooke Henderson, and our 2019 charity ambassador Kyle Hayhoe . A railroad serves as the arteries of a nation; at its heart is community and the people who make up these communities . Through our CP Has Heart program, we continue to demonstrate our commitment to the communities in which we live and operate . We’ve made it our mission to help improve the heart health of everyone in North America – men, women and children – through our strategic partnerships, sponsorships, activities and contributions that aid cardiovascular research and help fund the very best equipment for cardiac patients . -

Priority List Report

Priority List Report https://ocs-lpga.com/pmws/membindx.htm?v=6.3.6 2018 LPGA Priority List MAY-08-2018 1. Top-80: Top 80: Members in the top 80 (and ties) on the previous year's season-ending Money List. Priority is based on the order of the list. Ties will be broken by the Members' positions on the Career Money List as of the end of the previous year. 1. Sung Hyun Park 28. Chella Choi 55. Jane Park 2. So Yeon Ryu 29. Katherine Kirk 56. Nicole Broch Larsen 3. Lexi Thompson 30. Brittany Altomare 57. Kim Kaufman 4. Shanshan Feng 31. Jodi Ewart Shadoff 58. Sandra Gal 5. Ariya Jutanugarn 32. Brittany Lincicome 59. Ayako Uehara 6. Brooke M. Henderson 33. Austin Ernst 60. Alena Sharp 7. Cristie Kerr 34. Gerina Piller 61. Pernilla Lindberg 8. Anna Nordqvist 35. Haru Nomura 62. Azahara Munoz 9. Moriya Jutanugarn 36. Jenny Shin 63. Mo Martin 10. Sei Young Kim 37. Suzann Pettersen 64. Gaby Lopez 11. In Gee Chun 38. Hyo Joo Kim 65. Jing Yan 12. In-Kyung Kim 39. Caroline Masson 66. Peiyun Chien 13. Lydia Ko 40. Karine Icher 67. Ally McDonald 14. Mi Jung Hur 41. Jacqui Concolino 68. Brittany Lang 15. Stacy Lewis 42. Ashleigh Buhai 69. Cydney Clanton 16. Minjee Lee 43. Megan Khang 70. Wei-Ling Hsu 17. Danielle Kang 44. Angel Yin 71. Sun Young Yoo 18. Amy Yang 45. Pornanong Phatlum 72. Laura Gonzalez Escallon 19. Michelle Wie 46. Charley Hull 73. Olafia Kristinsdottir 20. Mirim Lee 47. -

Madill Record ‘In the Arms of Lake Ttexoma’Exoma’

Thursday, Aug. 20 Friday, Aug. 21 Saturday, Aug. 22 Sunday, Aug. 23 Monday, Aug. 24 Tuesday, Aug. 26 Wednesday, Aug. 27 Heat Advisory High Temp: 92 High Temp: 93 High Temp: 95 High Temp: 97 High Temp: 97 High Temp: 96 High Temp: 96 Sunny Mostly Sunny Sunny Mostly Sunny Sunny Mostly Sunny Sunny The Madill Record ‘In the Arms of Lake TTexoma’exoma’ Vol. 125 — Number 59 Madill, Marshall CountyCounty,, OK 73446 — ThursdayThursday,, August 20, 2020 12 Pages in 2 Sections — $1 Changes coming to Marshall County Shalene White • The Madill Record Summer Bryant • The Madill Record The business that used to be known as Smiley’s (left) was purchased by ASAP Energy. They have been working on remodeling it to fit the business’ motif and plan to open soon. Super C Mart (right) placed a sign on the lot marked for the new building. The new location is one half of a mile east of their current location. High speed chase starts chain reaction By Shalene White to a black 1991 Harley David- and an older gentleman sitting through William Ray Park, tification and $319. detained. [email protected] son XTC; nowhere close to the in a white pickup. Beshirs down Rogers, and by Trinity After EMS loaded Dodd into Officers found more in- “Crotch Rocket.” Finding out followed a hunch again and Baptist Church, it proceeded the ambulance, and later flown dividuals as they swept the An incident on August 11 this information led officers to recommended surveying the down Highway 377. Reaching to Medical City Plano in critical house.