Why Emojis Should Not Satisfy the Statute of Frauds’ Writing Requirement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpha • Bravo • Charlie

ALPHA • BRAVO • CHARLIE Inspired by Alpha, Bravo, Charlie (published by Phaidon) these Perfect activity sheets introduce young people to four different nautical codes. There are messages to decode, questions to answer for curious and some fun facts to share with friends and family. 5-7 year olds FLAG IT UP These bright, colorful flags are known as signal flags. There is one flag for each letter of the alphabet. 1. What is the right-hand side of a ship called? Use the flags to decode the answer! 3. Draw and color the flag that represents the first letter of your name. 2. Draw and color flags to spell out this message: SHIP AHOY SH I P AHOY FUN FACT Each flag also has its own To purchase your copy of meaning when it's flown by 2. Alpha, Bravo, Charlie visit phaidon.com/childrens2016 itself. For example, the N flag by STARBOARD 1. itself means "No" or "Negative". Answers: ALPHA OSCAR KILO The Phonetic alphabet matches every letter with a word so that letters can’t be mixed up and sailors don’t get the wrong message. 1. Write in the missing first letters from these words in the Phonetic alphabet. What word have you spelled out? Write it in here: HINT: The word for things that are transported by ship. 2. Can you decode the answer to this question: What types of cargo did Clipper ships carry in the 1800s? 3. Use the Phonetic alphabet to spell out your first name. FUN FACT The Phonetic alphabet’s full name is the GOLD AND WOOL International Radiotelephony Spelling Alphabet. -

UNIT 2 Braille

Mathematics Enhancement Programme Codes and UNIT 2 Braille Lesson Plan 1 Braille Ciphers Activity Notes T: Teacher P: Pupil Ex.B: Exercise Book 1 Introduction T: What code, designed more than 150 years ago, is still used Whole class interactive extensively today? discussion. T: The system of raised dots which enables blind people to read was Ps might also suggest Morse code designed in 1833 by a Frenchman, Louis Braille. or semaphore. Does anyone know how it works? Ps might have some ideas but are T: Braille uses a system of dots, either raised or not, arranged in unlikely to know that Braille uses 3 rows and 2 columns. a 32× configuration. on whiteboard Here are some possible codes: ape (WB). T puts these three Braille letters on WB. T: What do you notice? (They use different numbers of dots) T: We will find out how many possible patterns there are. 10 mins 2 Number of patterns T: How can we find out how many patterns there are? Response will vary according to (Find as many as possible) age and ability. T: OK – but let us be systematic in our search. What could we first find? (All patterns with one dot) T: Good; who would like to display these on the board? P(s) put possible solutions on the board; T stresses the logical search for these. Agreement. Praising. (or use OS 2.1) T: Working in your exercise books (with squared paper), now find all possible patterns with just 2 dots. T: How many have you found? Allow about 5 minutes for this before reviewing. -

Seeing Emoji Rendering Differences Across Platforms

What I See is What You Don’t Get: The Effects of (Not) Seeing Emoji Rendering Differences across Platforms HANNAH MILLER HILLBERG, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA ZACHARY LEVONIAN, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA DANIEL KLUVER, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA LOREN TERVEEN, GroupLens Research, University of Minnesota, USA BRENT HECHT, Northwestern University, USA Emoji are popular in digital communication, but they are rendered differently on different viewing platforms (e.g., iOS, Android). It is unknown how many people are aware that emoji have multiple renderings, or whether they would change their emoji-bearing messages if they could see how these messages render on recipients’ devices. We developed software to expose the multi-rendering nature of emoji and explored whether this increased visibility would affect how people communicate with emoji. Through a survey of 710 Twitter users who recently posted an emoji-bearing tweet, we found that at least 25% of respondents were unaware that the emoji they posted could appear differently to their followers. Additionally, after being shown how one of their tweets rendered across platforms, 20% of respondents reported that they would have edited or not sent the tweet. These statistics reflect millions of potentially regretful tweets shared per day because people cannot see emoji rendering differences across platforms. Our results motivate the development of tools that increase the visibility of emoji rendering differences across platforms, and we 1 contribute our cross-platform emoji rendering software to facilitate this effort. 124 CCS Concepts: • Human-centered computing → Empirical studies in collaborative and social computing KEYWORDS Emoji; computer-mediated communication; cross-platform; rendering; invisibility of system status ACM Reference format: Hannah Miller Hillberg, Zachary Levonian, Daniel Kluver, Loren Terveen and Brent Hecht. -

Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis As Evidence Erin Janssen St

St. Mary's Law Journal Volume 49 | Number 3 Article 5 6-2018 Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence Erin Janssen St. Mary's University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Evidence Commons, Internet Law Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Erin Janssen, Hearsay in the Smiley Face: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence, 49 St. Mary's L.J. 699 (2018). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal/vol49/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Mary's Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Janssen: Analyzing the Use of Emojis as Evidence COMMENT HEARSAY IN THE SMILEY FACE: ANALYZING THE USE OF EMOJIS AS EVIDENCE ERIN JANSSEN* I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 700 II. Background ............................................................................................. 701 A. Federal Rules of Evidence ............................................................. 701 B. Free Speech and Technology ....................................................... -

Multimedia Data and Its Encoding

Lecture 14 Multimedia Data and Its Encoding M. Adnan Quaium Assistant Professor Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology Room – 4A07 Email – [email protected] URL- http://adnan.quaium.com/aust/cse4295 CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 1 Text Encoding The character by character encoding of an alphabet is called encryption. As a rule, this coding must be reversible – the reverse encoding known as decoding or decryption. Examples for a simple encryption are the international phonetic alphabet or Braille script CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 2 Text Encoding CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 3 Morse Code Samuel F. B. Morse and Alfred Vail used a form of binary encoding, i.e., all text characters were encoded in a series of two basic characters. The two basic characters – a dot and a dash – were short and long raised impressions marked on a running paper tape. Word borders are indicated by breaks. CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 4 Morse Code ● To achieve the most efficient encoding of the transmitted text messages, Morse and Vail implemented their observation that specific letters came up more frequently in the (English) language than others. ● The obvious conclusion was to select a shorter encoding for frequently used characters and a longer one for letters that are used seldom. CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 5 7 bit ASCII code CSE 4295 : Multimedia Communication prepared by M. Adnan Quaium 6 Unicode Standard ● The Unicode standard assigns a number (code point) and a name to each character, instead of the usual glyph. -

Speaking the Same Language: Data Standards and Disruptive Technologies in the Administration of Justice

Speaking the Same Language: Data Standards and Disruptive Technologies in the Administration of Justice David Colarusso* & Erika J. Rickard** I. INTRODUCTION While the legal profession is coming to grips with technological disruption, practitioners serving the needs of those with low and moderate-incomes find themselves struggling to keep up.1 Insufficient resources clearly impede large- scale technological improvements. Yet, the rise of civic coding and the growing legal technology sector suggest an untapped pool of civic and private resources ready to help address this shortfall.2 We argue that state trial courts are best positioned to leverage these resources for the benefit of low and moderate- income individuals by addressing a key structural impediment to innovation: the lack of clearly-defined judicial data standards. In private practice and legal education, innovative technologies have fueled competition from companies that provide document automation to the general public and leverage machine intelligence to remove the work of repetitive tasks, including matters involving rudimentary questions of judgment.3 While * Data Scientist, Massachusetts Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS); J.D., Boston University School of Law (2011); M.Ed., Harvard Graduate School of Education (2002). The opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not reflect those of CPCS or the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. ** Associate Director of Field Research, Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School, and Commissioner, Massachusetts Access to Justice Commission; J.D., Harvard Law School (2010). Portions of this Article derive from presentations made by the authors at the 2016 Suffolk University Law Review’s Legal Technology Symposium entitled, “A New Era of Lawyering: Integrating Law Practice with Innovative Technology.” Additional portions were adapted from a CPCS blog post accompanying a public comment in reply to the Massachusetts Trial Court’s 2016 proposed rule change regarding access to court records. -

How to Speak Emoji : a Guide to Decoding Digital Language Pdf, Epub, Ebook

HOW TO SPEAK EMOJI : A GUIDE TO DECODING DIGITAL LANGUAGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK National Geographic Kids | 176 pages | 05 Apr 2018 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007965014 | English | London, United Kingdom How to Speak Emoji : A Guide to Decoding Digital Language PDF Book Secondary Col 2. Primary Col 1. Emojis are everywhere on your phone and computer — from winky faces to frowns, cats to footballs. They might combine a certain face with a particular arrow and the skull emoji, and it means something specific to them. Get Updates. Using a winking face emoji might mean nothing to us, but our new text partner interprets it as flirty. And yet, once he Parenting in the digital age is no walk in the park, but keep this in mind: children and teens have long used secret languages and symbols. However, not all users gave a favourable response to emojis. Black musicians, particularly many hip-hop artists, have contributed greatly to the evolution of language over time. A collection of poems weaving together astrology, motherhood, music, and literary history. Here begins the new dawn in the evolution the language of love: emoji. She starts planning how they will knock down the wall between them to spend more time together. Irrespective of one's political standpoint, one thing was beyond dispute: this was a landmark verdict, one that deserved to be reported and analysed with intelligence - and without bias. Though somewhat If a guy likes you, he's going to make sure that any opportunity he has to see you, he will. Here and Now Here are 10 emoticons guys use only when they really like you! So why do they do it? The iOS 6 software. -

Designing the Haptic Interface for Morse Code Michael Walker University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-31-2016 Designing the Haptic Interface for Morse Code Michael Walker University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons, Communication Commons, and the Neurosciences Commons Scholar Commons Citation Walker, Michael, "Designing the Haptic Interface for Morse Code" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6600 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Designing the Haptic Interface for Morse Code by Michael Walker A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering College of Engineering University of South Florida Major Professor: Kyle Reed, Ph.D. Stephanie Carey, Ph.D. Don Dekker, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 24, 2016 Keywords: Bimanual, Rehabilitation, Pattern, Recognition, Perception Copyright © 2016, Michael Walker ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Kyle Reed, for providing guidance for my first steps in research work and exercising patience and understanding through my difficulties through the process of creating this thesis. I am thankful for my colleagues in REED lab, particularly Benjamin Rigsby and Tyagi Ramakrishnan, for providing helpful insight in the design of my experimental setup. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ -

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech

The Emoji Factor: Humanizing the Emerging Law of Digital Speech 1 Elizabeth A. Kirley and Marilyn M. McMahon Emoji are widely perceived as a whimsical, humorous or affectionate adjunct to online communications. We are discovering, however, that they are much more: they hold a complex socio-cultural history and perform a role in social media analogous to non-verbal behaviour in offline speech. This paper suggests emoji are the seminal workings of a nuanced, rebus-type language, one serving to inject emotion, creativity, ambiguity – in other words ‘humanity’ - into computer mediated communications. That perspective challenges doctrinal and procedural requirements of our legal systems, particularly as they relate to such requisites for establishing guilt or fault as intent, foreseeability, consensus, and liability when things go awry. This paper asks: are we prepared as a society to expand constitutional protections to the casual, unmediated ‘low value’ speech of emoji? It identifies four interpretative challenges posed by emoji for the judiciary or other conflict resolution specialists, characterizing them as technical, contextual, graphic, and personal. Through a qualitative review of a sampling of cases from American and European jurisdictions, we examine emoji in criminal, tort and contract law contexts and find they are progressively recognized, not as joke or ornament, but as the first step in non-verbal digital literacy with potential evidentiary legitimacy to humanize and give contour to interpersonal communications. The paper proposes a separate space in which to shape law reform using low speech theory to identify how we envision their legal status and constitutional protection. 1 Dr. Kirley is Barrister & Solicitor in Canada and Seniour Lecturer and Chair of Technology Law at Deakin University, MelBourne Australia; Dr. -

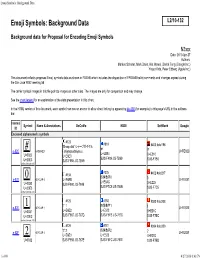

Emoji Symbols: Background Data

Emoji Symbols: Background Data Emoji Symbols: Background Data Background data for Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols N3xxx Date: 2010-Apr-27 Authors: Markus Scherer, Mark Davis, Kat Momoi, Darick Tong (Google Inc.) Yasuo Kida, Peter Edberg (Apple Inc.) This document reflects proposed Emoji symbols data as shown in FDAM8 which includes the disposition of FPDAM8 ballot comments and changes agreed during the San José WG2 meeting 56. The carrier symbol images in this file point to images on other sites. The images are only for comparison and may change. See the chart legend for an explanation of the data presentation in this chart. In the HTML version of this document, each symbol row has an anchor to allow direct linking by appending #e-4B0 (for example) to this page's URL in the address bar. Internal Symbol Name & Annotations DoCoMo KDDI SoftBank Google ID Enclosed alphanumeric symbols #123 #818 'Sharp dial' シャープダイヤル #403 #old196 # # # e-82C ⃣ HASH KEY 「shiyaapudaiyaru」 U+FE82C U+EB84 U+0023 U+E6E0 U+E210 SJIS-F489 JIS-7B69 U+20E3 SJIS-F985 JIS-7B69 SJIS-F7B0 unified (Unicode 3.0) #325 #134 #402 #old217 0 四角数字0 0 e-837 ⃣ KEYCAP 0 U+E6EB U+FE837 U+E5AC U+0030 SJIS-F990 JIS-784B U+E225 U+20E3 SJIS-F7C9 JIS-784B SJIS-F7C5 unified (Unicode 3.0) #125 #180 #393 #old208 1 '1' 1 四角数字1 1 e-82E ⃣ KEYCAP 1 U+FE82E U+0031 U+E6E2 U+E522 U+E21C U+20E3 SJIS-F987 JIS-767D SJIS-F6FB JIS-767D SJIS-F7BC unified (Unicode 3.0) #126 #181 #394 #old209 '2' 2 四角数字2 e-82F KEYCAP 2 2 U+FE82F 2⃣ U+E6E3 U+E523 U+E21D U+0032 SJIS-F988 JIS-767E SJIS-F6FC JIS-767E SJIS-F7BD -

Emoticon Style: Interpreting Differences in Emoticons Across Cultures

Emoticon Style: Interpreting Differences in Emoticons Across Cultures Jaram Park Vladimir Barash Clay Fink Meeyoung Cha Graduate School of Morningside Analytics Johns Hopkins University Graduate School of Culture Technology, KAIST [email protected] Applied Physics Laboratory Culture Technology, KAIST [email protected] clayton.fi[email protected] [email protected] Abstract emotion not captured by language elements alone (Lo 2008; Gajadhar and Green 2005). With the advent of mobile com- Emoticons are a key aspect of text-based communi- cation, and are the equivalent of nonverbal cues to munications, the use of emoticons has become an everyday the medium of online chat, forums, and social media practice for people throughout the world. Interestingly, the like Twitter. As emoticons become more widespread emoticons used by people vary by geography and culture. in computer mediated communication, a vocabulary Easterners, for example employ a vertical style like ^_^, of different symbols with subtle emotional distinctions while westerners employ a horizontal style like :-). This dif- emerges especially across different cultures. In this pa- ference may be due to cultural reasons since easterners are per, we investigate the semantic, cultural, and social as- known to interpret facial expressions from the eyes, while pects of emoticon usage on Twitter and show that emoti- westerners favor the mouth (Yuki, Maddux, and Masuda cons are not limited to conveying a specific emotion 2007; Mai et al. 2011; Jack et al. 2012). or used as jokes, but rather are socio-cultural norms, In this paper, we study emoticon usage on Twitter based whose meaning can vary depending on the identity of the speaker. -

New Emoji Requests from Twitter Users: When, Where, Why, and What We Can Do About Them

1 New Emoji Requests from Twitter Users: When, Where, Why, and What We Can Do About Them YUNHE FENG, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA ZHENG LU, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA WENJUN ZHOU, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA ZHIBO WANG, Wuhan University, China QING CAO∗, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA As emojis become prevalent in personal communications, people are always looking for new, interesting emojis to express emotions, show attitudes, or simply visualize texts. In this study, we collected more than thirty million tweets mentioning the word “emoji” in a one-year period to study emoji requests on Twitter. First, we filtered out bot-generated tweets and extracted emoji requests from the raw tweets using a comprehensive list of linguistic patterns. To our surprise, some extant emojis, such as fire and hijab , were still frequently requested by many users. A large number of non-existing emojis were also requested, which were classified into one of eight emoji categories by Unicode Standard. We then examined patterns of new emoji requests by exploring their time, location, and context. Eagerness and frustration of not having these emojis were evidenced by our sentiment analysis, and we summarize users’ advocacy channels. Focusing on typical patterns of co-mentioned emojis, we also identified expressions of equity, diversity, and fairness issues due to unreleased but expected emojis, and summarized the significance of new emojis on society. Finally, time- continuity sensitive strategies at multiple time granularity levels were proposed to rank petitioned emojis by the eagerness, and a real-time monitoring system to track new emoji requests is implemented.