The Shire & Notting Hill1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College

Inklings Forever Volume 5 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Article 14 Friends 6-2006 An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Huff, Randy (2006) "An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton," Inklings Forever: Vol. 5 , Article 14. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol5/iss1/14 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume V A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2006 Upland, Indiana An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Huff, Randy. “An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton.” Inklings Forever 5 (2006) www.taylor.edu/cslewis An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff G.K. Chesterton was regarded by friend and foe as he enters, it is built wrong.”6 In the conclusion to a man of genius, a defender of the faith, a debater and What’s Wrong with the World, he sums it up thus: conversationalist par excellence. -

The Defendant (Winter, 2016)

The DEFENDANT Newsletter of the Australian Chesterton Society Vol. 23 No. 3 Winter 2016 Issue No. 90 ‘I have found that humanity is not The Unexpected incidentally engaged, but eternally and Chestertonians systematically engaged, by Karl Schmude in throwing gold into the Chesterton had a singular gift for inspiring gutter and diamonds into and not simply influencing his readers. Mahatma Gandhi the sea. ; therefore I Most, one would assume, were people who have imagined that the instinctively shared his perspectives and main business of man, values, but there were also those who would however humble, is have to be regarded as surprisingly affected defence. I have conceived by his writings. that a defendant is chiefly Two such figures were Mahatma Gandhi required when worldlings and Michael Collins. Both played a crucial Michael Collins despise the world – that part in the independence movements of a counsel for the defence their respective countries, India and Ireland, Gandhi was deeply impressed by an article would not have been out and both acknowledged the inspirational on Indian nationalism that Chesterton of place in the terrible day impact of Chesterton at decisive moments wrote for the Illustrated London News in in their lives. 1909. when the sun was darkened over Calvary and Man was rejected of men.’ Come to Campion - for the 2016 Conference The next conference of the Australian Chesterton Society will take place at Campion College on G.K. Chesterton, ‘Introduction’, Saturday, October 29, and a flyer is inserted with this issue of The Defendant. The Defendant (1901) The Unexpected One of the papers will focus on Chesterton and Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964), the American Chestertonians Catholic writer of novels and short stories. -

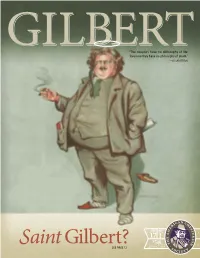

Saintgilbert?

“The skeptics have no philosophy of life because they have no philosophy of death.” —G.K. chesTERTON VOL NO 17 1 $550 SEPT/OCT 2013 . Saint Gilbert?SEE PAGE 12 . rton te So es l h u C t i Order the American e o n h T nd E nd d e 32 s Chesterton Society u 32 l c E a t g io in n th , E y co ver Annual Conference Audio nomics & E QTY. Dale Ahlquist, President of the American QTY. Carl Hasler, Professor of Philosophy, QTY. Kerry MacArthur, Professor of English, Chesterton Society Collin College University of St. Thomas “The Three Es” (Includes “Chesterton and Wendell “How G.K. Chesterton Dale’s exciting announce- Berry: Economy of Scale Invented Postmodern ment about GKC’s Cause) and the Human Factor” Literature” QTY. Chuck Chalberg as G.K. Chesterton QTY. Joseph Pearce, Writer-in-Residence and QTY. WIlliam Fahey, President of Thomas Professor of Humanities at Thomas More More College of the Liberal Arts Eugenics and Other Evils College; Co-Editor of St. Austin Review “Beyond an Outline: The “Chesterton and The Hobbit” QTY. James Woodruff, Teacher of Forgotten Political Writings Mathematics, Worcester Academy of Belloc and Chesterton” QTY. Kevin O’Brien’ s Theatre of the Word “Chesterton & Macaulay: two Incorporated presents histories, two QTY. Aaron Friar (converted to Eastern Orthodoxy as a result of reading a book Englands” “Socrates Meets Jesus” By Peter Kreeft called Orthodoxy) QTY. Pasquale Accardo, Author and Professor “Chesterton and of Pediatric Medicine QTY. Peter Kreeft, Author and Professor of Eastern Orthodoxy” “Shakespeare’s Most Philosophy, Boston College Catholic Play” The Philosophy of DVD bundle: $120.00 G.K. -

G K Chesterton

G.K. CHESTERTON: A LIFE Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in Kensington in 1874, educated at St. Paul’s School and the Slade School of Art where it was found that his primary talents were in the direction of writing. His earliest work was done in the family home and later at the publishers’ offices of Redway and T Fisher Unwin, and in the hurly burly of Fleet Street. It was his marriage to Frances Blogg in 1901 which turned his thoughts to a permanent home where he could continue his writing and find some quiet from the busy life as a journalist. The early years of marriage were spent in Kensington and Overstrand Mansions at Battersea, and it was from the latter that one day they took a second honeymoon journey to Slough from a station they had reached by chance on a bus labelled ‘Hanwell’. From Slough they walked through the beech woods to Beaconsfield, staying at the White Hart Hotel and decided ‘This is the sort of place where someday we will make our home’. This proved possible in 1909 when they rented Overroads, which had just been built in Grove Road. Their hopes of having children had by this time faded and they busied themselves with entertaining the children of their friends. Charades and other such games were an excuse for assembling cloaks and hats, bringing swords out of the umbrella stands or sheets from the beds. Despite the disappointment, children played a great part in their life and many local children had drawings done for them, skilfully but hastily drafted and full of humour. -

Detective Fiction Reinvention and Didacticism in G. K. Chesterton's

Detective Fiction Reinvention and Didacticism in G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown Clifford James Stumme Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of English College of Arts and Science Liberty University Stumme 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................3 Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................4 Historical and Autobiographical Context ....................................................................................6 Detective Fiction’s Development ..............................................................................................10 Chesterton, Detective Fiction, and Father Brown ......................................................................21 Chapter 2: Paradox as a Mode for Meaning ..................................................................................32 Solution Revealing Paradox .......................................................................................................34 Plot Progressing Paradox ...........................................................................................................38 Truth Revealing Paradox ...........................................................................................................41 Chapter 3: Opposition in Character and Ideology .........................................................................49 -

GK Chesterton

THE SAGE DIGITAL LIBRARY APOLOGETICS HERETICS by Gilbert K. Chesterton To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the SAGE Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: M AKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. SAGE Software Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1996 2 HERETICS by Gilbert K. Chesterton SAGE Software Albany, Oregon © 1996 3 “To My Father” 4 The Author Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in London, England on the 29th of May, 1874. Though he considered himself a mere “rollicking journalist,” he was actually a prolific and gifted writer in virtually every area of literature. A man of strong opinions and enormously talented at defending them, his exuberant personality nevertheless allowed him to maintain warm friendships with people — such as George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells — with whom he vehemently disagreed. Chesterton had no difficulty standing up for what he believed. He was one of the few journalists to oppose the Boer War. His 1922 “Eugenics and Other Evils” attacked what was at that time the most progressive of all ideas, the idea that the human race could and should breed a superior version of itself. In the Nazi experience, history demonstrated the wisdom of his once “reactionary” views. His poetry runs the gamut from the comic 1908 “On Running After One’s Hat” to dark and serious ballads. During the dark days of 1940, when Britain stood virtually alone against the armed might of Nazi Germany, these lines from his 1911 Ballad of the White Horse were often quoted: I tell you naught for your comfort, Yea, naught for your desire, Save that the sky grows darker yet And the sea rises higher. -

Gilbert Keith Chesterton - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gilbert Keith Chesterton - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gilbert Keith Chesterton(29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) Gilbert Keith Chesterton was an English writer. He published works on philosophy, ontology, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism, biography, Christian apologetics, and fiction, including fantasy and detective fiction. Chesterton has been called the "prince of paradox". Time magazine, in a review of a biography of Chesterton, observed of his writing style: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out." For example, Chesterton wrote "Thieves respect property. They merely wish the property to become their property that they may more perfectly respect it." Chesterton is well known for his reasoned apologetics and even some of those who disagree with him have recognized the universal appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. Chesterton, as a political thinker, cast aspersions on both progressivism and conservatism, saying, "The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected." Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify such a position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Roman Catholicism -

Common Sense and Humor in the Friendship of GK Chesterton And

Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 Volume 10 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Tenth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on Article 76 C.S. Lewis & Friends 6-5-2016 Well Met: Common Sense and Humor in the Friendship of G. K. Chesterton and Dorothy L. Sayers Barbara M. Prescott Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Prescott, Barbara M. (2016) "Well Met: Common Sense and Humor in the Friendship of G. K. Chesterton and Dorothy L. Sayers," Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016: Vol. 10 , Article 76. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol10/iss1/76 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Well Met: Common Sense and Humor in the Friendship of G.K. Chesterton and Dorothy L. Sayers by Barbara M. Prescott Barbara Mary Prescott, M.A., M.Ed., is a researcher of writing communities and the writing process. She has advanced degrees from the University of Illinois and the University of Wisconsin, including post-graduate research in Language and Literacy at Stanford University. She has published numerous articles on the writing process and is currently researching the poetry of Dorothy L. -

The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton

The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton Originally Published 1925 This book is in the Public Domain The Everlasting Man by G.K. Chesterton Prefatory Note........................................................................................................... 3 Introduction The Plan Of This Book .......................................................................... 3 Part I On the Creature Called Man.......................................................................... 10 I. The Man in the Cave .......................................................................................... 10 II. Professors and Prehistoric Men .......................................................................... 22 III. The Antiquity of Civilisation............................................................................. 32 IV. God and Comparative Religion...................................................................... 50 V. Man and Mythologies........................................................................................ 62 VI. The Demons and the Philosophers............................................................... 72 VII. The War of the Gods and Demons .............................................................. 86 VIII. The End of the World .................................................................................... 96 Part II On the Man Called Christ............................................................................ 106 I. The God in the Cave ....................................................................................... -

G.K. Chesterton: a Select Bibliography

G.K. Chesterton: A Select Bibliography This is not a comprehensive listing of Chesterton’s works. For a more complete list, please see the following: Sullivan, John. G.K. Chesterton: A Bibliography. London: University of London Press Ltd., 1958. ---. Chesterton Continued: A Bibliographical Supplement. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1969. ---. Chesterton Three: A Bibliographical Postscript. Bedford, G.B.: Vintage Publ., 1980. DRAMA -Magic (1913) -The Judgment of Dr. Johnson (1927) -The Surprise (1952) ESSAY COLLECTIONS -The Defendant (1901) -Twelve Types (1902) -Varied Types (1903) -All Things Considered (1908) -Tremendous Trifles (1909) -Alarms and Discursions (1910) -Miscellany of Men (1912) -Utopia of Usurers (1917) - How to Help Annexation (1918) -The Uses of Diversity (1920) -What I Saw in America (1922) -Fancies vs. Fads (1923) -Generally Speaking (1928) -Come to Think of It (1930) -All is Grist (1931) -Sidelights on New London and Newer York (1932) -All I Survey (1933) -Avowals and Denials (1934) -The Well and the Shallows (1935) -As I was Saying (1936) -The End of the Armistice (1940) -The Common Man (1950) -The Glass Walking-Stick (1955) -Lunacy and Letters (1958) -Where All Roads Lead (1961) -The Spice of Life (1965) -Chesterton on Shakespeare (1972) -The Apostle and the Wild Ducks (1975) -In Defense of Sanity: The Best Essays of G.K. Chesterton ed. by Dale Ahlquist, Joseph Pearce, and Aidan Mackey (Ignatius Press, 2011) Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL FICTION -The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904) -The Club of Queer -

Mental Pictures: Shapes and Colors in the Thought of G.K. Chesterton William L

Inklings Forever Volume 7 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 9 Lewis & Friends 6-3-2010 Mental Pictures: Shapes and Colors in the Thought of G.K. Chesterton William L. Isley Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Isley, William L. Jr. (2010) "Mental Pictures: Shapes and Colors in the Thought of G.K. Chesterton," Inklings Forever: Vol. 7 , Article 9. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol7/iss1/9 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume VII A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2010 Upland, Indiana Mental Pictures Shapes and Colors in the Thought of G. K. Chesterton William L. Isley, Jr. Although Chesterton is not what would normally be considered a systematic thinker, his writings exhibit a marked consistency of thought by means of a series of recurrent images. In order to understand how Chesterton thinks; therefore, it is best to follow these series of images. An examination of the contrasting images he uses to critique as modes of madness both Impressionism in The Man Who Was Thursday and rationalism in The Flying Inn will demonstrate the validity of this approach to Chesterton. -

Chesterton Cure 2020 Is Book Presents 100 of the Most Common FATIMA MYSTERIES by VICTORIA DARKEY the DEBATER

2 29 30 Tremendous Trifles 2 Signature of Man Beauty and the Factory 29 Truth in the State of Transmission The Everlasting Family 30 The CHESTERTON THE MAGAZINE OF THE APOSTOLATE OF COMMON SENSE CURE Report on the 39th Annual Chesterton Conference … PAGE 7 . . VOL . NO. 24 01 $ 95 9 SEPT/OCT 2020 GREAT BOOKS & FILMS ON FATIMA u FATIMA FOR TODAY e Urgent Marian Message of Hope Fr. Andrew Apostoli, CFR In this authoritative, up to date book,NEW! Fr. Apostoli, foremost Fatima expert, carefully analyzes the Marian apparitions, requests, and amazing miraclesFATIMA that took place in Fatima, and clears up lingering questions about their meaning. He challenges the reader to hear anew the call of Our Lady to p100rayer Questions and sacri and ce Answers in rep aboutaration the for sin and for the conversion of the world. 16 pages of photos.Marian Apparitions — Paul Senz he Blessed Virgin appeared six times Produced by the lmmakers of the acclaimed e 13th Day, this powerful documentary combines ATOP . Sewnin So1917 cover,to three $18.95shepherd FINDINGchildren in FATIMA — T experts to tell the whole story of Our Lady of Fatima. archival footage,the dramatic tiny village reenactments, of Fatima, Portugal.and original einterviews with Fatima FFFAM . 90 mins, $14.95 story and message of these apparitions have gripped the imagination of people all over the world, including simple believers, FATIMA FOR TODAY theologians, skeptics, scientists and popes. e Urgent Marian Message of Hope is book presents 100 of the most common FATIMA MYSTERIES questions, with detailed answers, to explore Fr.