Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision O/589/19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview Summary

FIND A DEALERSHIP OVERVIEW SUMMARY DEFENDER CELEBRATION SERIES FIND A DEALERSHIP OVERVIEW SUMMARY LAND ROVER DEFENDER CELEBRATION SERIES For some 67 years, The Land Rover – rechristened Defender in 1990 – has crisscrossed the globe like no other vehicle. It has traversed terrains others simply could only dream of. It has forged lasting partnerships with such organisations as the Red Cross and Royal Geographical Society and has proved itself against all-comers on such gruelling challenges as the Dakar Rally. Now this iconic part of our history is set to continue with three Limited Edition vehicles being produced to celebrate its life. FIND A DEALERSHIP OVERVIEW SUMMARY Land Rover Defender’s boundless capability has taken it to all four corners of the earth. For instance, back in 1955, it was the first vehicle in the world to go overland from London to Singapore. It has worked in territories as diverse as Africa and Alaska. It has proved to be the most robust and unrelenting workhorse on farms, in jungles and deserts, delivered time after time in such industries as mining and engineering. Its heritage is without question. Its legacy, without equal. Top left and right: © British Motor Industry Heritage Trust. Bottom left: © Nick Dimbleby Photographer. Botton right: © The Red Cross emblem is shown with the kind permission of the British Red Cross Society; Vehicle used by the Sierra Leone Red Cross Society to support local community projects. FIND A DEALERSHIP OVERVIEW SUMMARY FIND A DEALERSHIP OVERVIEW SUMMARY DEFENDER HERITAGE LIMITED EDITION The Heritage Limited Edition vehicle taps into Defender’s rich lode of capability whilst delivering a thoroughly modern interpretation of the original Land Rover built to the most demanding specifications. -

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 8/21 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

The Elkhart Collection Lot Price Sold 1037 Hobie Catamaran $1,560.00 Sold 1149 2017 John Deere 35G Hydraulic Excavator (CHASSIS NO

Auction Results The Elkhart Collection Lot Price Sold 1037 Hobie Catamaran $1,560.00 Sold 1149 2017 John Deere 35G Hydraulic Excavator (CHASSIS NO. 1FF035GXTHK281699) $44,800.00 Sold 1150 2016 John Deere 5100 E Tractor (CHASSIS NO. 1LV5100ETGG400694) $63,840.00 Sold 1151 Forest River 6.5×12-Ft. Utility Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 5NHUAS21X71032522) $2,100.00 Sold 1152 2017 Bravo 16-Ft. Enclosed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 542BE1825HB017211) $22,200.00 Sold 1153 2011 No Ramp 22-Ft. Ramp-Less Open Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 1P9BF2320B1646111) $8,400.00 Sold 1154 2015 Bravo 32-Ft. Tag-Along Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 542BE322XFB009266) $24,000.00 Sold 1155 2018 PJ Trailers 40-Ft. Flatbed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 4P5LY3429J3027352) $19,800.00 Sold 1156 2016 Ford F-350 Super Duty Lariat 4×4 Crew-Cab Pickup (CHASSIS NO. 1FT8W3DT2GEC49517) $64,960.00 Sold 1157 2007 Freightliner Business Class M2 Crew-Cab (CHASSIS NO. 1FVACVDJ87HY37252) $81,200.00 Sold 1158 2005 Classic Stack Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 10WRT42395W040450) $51,000.00 Sold 1159 2017 United 20-Ft. Enclosed Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 56JTE2028HA156609) $7,200.00 Sold 1160 1997 S&S Welding 53 Transport Trailer (IDENTIFICATION NO. 1S9E55320VG384465) $33,600.00 Sold 1161 1952 Ford 8N Tractor (CHASSIS NO. 8N454234) $29,120.00 Sold 1162 1936 Port Carling Sea Bird (HULL NO. 3962) $63,000.00 Sold 1163 1961 Hillman Minx Convertible Project (CHASSIS NO. B1021446 H LCX) $3,360.00 Sold 1164 1959 Giulietta Super Sport (FRAME NO. GTD3M 1017) $9,600.00 Sold 1165 1959 Atala 'Freccia d’Oro' (FRAME NO. S 14488) $9,000.00 Sold 1166 1945 Willys MB (CHASSIS NO. -

SAV Medidas Arg. 04/2006

RETENES ORDENADOS POR MEDIDA DE EJE EjeAloj. Alt. Tipo N° SAV Orient. Comp. EjeAloj. Alt. Tipo N° SAV Orient. Comp. 4.55 14.50 7.00 G002 7020 L NBR 12.00 20.00 9,00/11,00 Lw03 7508 L NBR . 22.00 4.50 Lx 10017 L NBR 4.80 22.00 7.00 Ls 10857 L NBR . 22.00 5.00 Lx 7682 L NBR . 22.00 6.00 Lx 7304 L NBR 5.00 15.00 6.00 Lt 6190 L NBR . 22.00 7.00 Lx 5818 L NBR . 18.00 8.00 Ls 10681 L NBR Kz . 24.00 5.00 Lx 10425 L NBR . 24.00 7.00 Lx 10211 L NBR 5.55 25.32 4.76 Lt 6193 L NBR . 25.00 7.00 Lx 10210 L NBR . 25.40 8.00 Lx 10556 L NBR 6.00 22.00 7.00 Lx 7355 L NBR . 26.00 8.00 Lz 6220 L NBR . 22.00 8.35 G011 7836 L NBR . 28.00 7.00 Lx 7352 L NBR Kx . 28.00 7.00 Lx 10748 L NBR 6.34 19.00 6.15 Lt 6195 L NBR . 28.00 7,50/8,50 Lw41 10916 L FPM . 30.00 8.00 Lz 5136 L NBR 6.35 19.05 5.55 Lt 6197 L NBR . 30.00 13.00 Lz 5137 L NBR . 32.00 7.00 Lz 5319 L NBR 6.80 22.00 7.00 Lx 7689 L NBR . 14.0/20.0 9,00/10,50 Lx15 10410 L NBR Kt 7.82 15.90 5.00 Lt 6198 L NBR 12.30 32.00 7.85 Lx 6784 L NBR 7.90 16.00 6.00 Lz 6898 L NBR 12.41 33.90 3,30/9,60 Lx09 7250 L NBR . -

New Range Rover Sport Find a Retailer Contents Specifications Build Your Own

FIND A RETAILER CONTENTS SPECIFICATION BUILD YOUR OWN NEW RANGE ROVER SPORT FIND A RETAILER CONTENTS SPECIFICATIONS BUILD YOUR OWN Ever since the first Land Rover vehicle was conceived in 1947, we have built vehicles that challenge what is possible. These in turn have challenged their owners to explore new territories and conquer difficult terrains. Our vehicles epitomize the values of the designers and engineers who have created them. Each one instilled with iconic British design cues, delivering capability with composure. Which is how we continue to break new ground, defy conventions and encourage each other to go further. Land Rover truly enables you to make more of your world, to go above and beyond. FIND A RETAILER CONTENTS SPECIFICATIONS BUILD YOUR OWN THE NEW RANGE ROVER SPORT The New Range Rover Sport is undoubtedly our most dynamic SUV ever. Performance and capability are exceptional; and a range of advanced technologies are designed to deliver an improved driving experience. With sportier design cues and a powerful, muscular stance, this is a vehicle designed to create an impression. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION VERSATILITY Introducing the New Range Rover Sport 6 Truly Flexible 44 Introducing the New 2019 Range Rover Sport 8 Business 46 Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle* Leisure 47 Towing 49 DESIGN Exterior 11 RANGE ROVER SPORT SVR Interior 13 Performance and Design 51 Interior 52 PERFORMANCE AND CAPABILITY New 2019 Range Rover Sport Plug-in SPECIFICATIONS Hybrid Electric Vehicle* 14 Choose Your Model 54 Engines and Transmission 18 Choose Your Engine 64 Legendary Breadth of Capability 23 Choose Your Exterior 66 Choose Your Wheels 74 TECHNOLOGY Choose Your Interior 76 Infotainment 27 Choose Your Options and Land Rover Gear 80 Connectivity 28 Technical Details 84 Audio 32 Driver Assistance 34 WORLD OF LAND ROVER 86 Efficient Technologies 38 YOUR PEACE OF MIND 89 DRIVER ASSISTANCE Driver Assistance 40 Lighting Technology 43 *Vehicle’s estimated availability is Summer 2018. -

Automotive Sector in Tees Valley

Invest in Tees Valley A place to grow your automotive business Invest in Tees Valley Recent successes include: Tees Valley and the North East region has April 2014 everything it needs to sustain, grow and Nifco opens new £12 million manufacturing facility and Powertrain and R&D plant develop businesses in the automotive industry. You just need to look around to June 2014 see who is already here to see the success Darchem opens new £8 million thermal of this growing sector. insulation manufacturing facility With government backed funding, support agencies September 2014 such as Tees Valley Unlimited, and a wealth of ElringKlinger opens new £10 million facility engineering skills and expertise, Tees Valley is home to some of the best and most productive facilities in the UK. The area is innovative and forward thinking, June 2015 Nifco announces plans for a 3rd factory, helping it to maintain its position at the leading edge boosting staff numbers to 800 of developments in this sector. Tees Valley holds a number of competitive advantages July 2015 which have helped attract £1.3 billion of capital Cummins’ Low emission bus engine production investment since 2011. switches from China back to Darlington Why Tees Valley should be your next move Manufacturing skills base around half that of major cities and a quarter of The heritage and expertise of the manufacturing those in London and the South East. and engineering sector in Tees Valley is world renowned and continues to thrive and innovate Access to international markets Major engineering companies in Tees Valley export Skilled and affordable workforce their products around the world with our Tees Valley has a ready skilled labour force excellent infrastructure, including one of the which is one of the most affordable and value UK’s leading ports, the quickest road connections for money in the UK. -

Range Rover Evoque

FIND A RETAILER BUILD YOUR OWN OVERVIEW SPECIFICATION RANGE ROVER EVOQUE ENGINE MODEL COLOUR WHEELS INTERIOR ACCESSORIES TECHNICAL DETAILS FIND A RETAILER BUILD YOUR OWN OVERVIEW SPECIFICATION THE EVOQUE MARKS A BOLD EVOLUTION OF RANGE ROVER DESIGN. WITH ITS DRAMATIC RISING BELTLINE, A MUSCULAR SHOULDER RUNNING THE LENGTH OF THE CAR, AND A DISTINCTIVE TAPER TO THE FLOATING ROOFLINE, THE RANGE ROVER EVOQUE ADOPTS A VERY DYNAMIC PROFILE WITH A POWERFUL AND ATHLETIC STANCE. Gerry McGovern. Land Rover Design Director and Chief Creative Officer. DESIGN DRIVING TECHNOLOGY FINISHING TOUCHES ENGINES BODY AND CHASSIS SAFETY ENVIRONMENTAL FIND A RETAILER BUILD YOUR OWN OVERVIEW SPECIFICATION DESIGN With its striking lines, muscular shoulder Optional adaptive full LED headlamps and tapered roof, Range Rover Evoque complement the vehicle’s design cues by EXTERIOR sets itself apart from its contemporaries. combining a distinctive look with enhanced light output for better visibility and safety Whether discovering hidden parts of town at night. The headlamps adaptive function or being seen in all the right places, it’s enables light beams to be automatically always ready for action. Striking the perfect aligned with steering inputs and follow balance between distinctive exterior curves in the road. design, a contoured cabin, capability and performance, the vehicle defines The Daytime Running Lights (DRLs) have a contemporary city life. new shape creating a distinctive signature which also serves as the directional Image shown is HSE Dynamic five-door in Yulong White. indicator where it flashes amber. DESIGN DRIVING TECHNOLOGY FINISHING TOUCHES ENGINES BODY AND CHASSIS SAFETY ENVIRONMENTAL FIND A RETAILER BUILD YOUR OWN OVERVIEW SPECIFICATION COUPÉ With its sleek lines Range Rover Evoque Coupé delivers a bold interpretation of contemporary British design. -

British Invasion XXX

Welcome to British Invasion XXX September 10th-12th, 2021 Welcome to the 30th British Invasion in Stowe Vermont! “The Tradition Continues.” Over the past 30 years the British Invasion has grown to become the largest annual All British Motorcar Show and British Lifestyle Event in the United States, annually attracting between 600 & 650 British Motorcars to the scenic mountain village of Location for 2021 Stowe Vermont. For many, the annual pilgrimage to Stowe is the highlight of their motoring experience for the year. The allure of the mountains, the back roads, and DIRECTIONS TO onset of the Fall Harvest Season adds to the sound of British motors resonating off STOWE, VT AND of the pine trees. BRITISH INVASION XXX This event is your event, and with your participation and support and by sharing your experiences with friends and fellow enthusiasts, we have continued to grow Exit 10 off Vermont the British Invasion from year to year. This year we honor “Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Austin-Healey & Singer” as our featured marques. 2021 also marks the twentieth Interstate 89 onto Route year of Participation of the Singer Owners Club and will be commemorated with 100 North to Stowe. their own unique and memorable Car Club Display. Special welcome to the Rolls- Follow Route 100 for Royce Owners Club / Bentley Drivers Club who have chosen to join this year’s celebration with their Special, “Mini Meet.” 10 miles to three-way stop in downtown We ask that you show consideration for your fellow British Motorcar Enthusiasts by Stowe. Left onto Route voting fairly and honestly for cars in the many classes on the show grounds. -

P 01.Qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1

p 01.qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1 June 27, 2005 © 2005 Crain Communications GmbH. All rights reserved. €14.95; or equivalent 20052005 GlobalGlobal MarketMarket DataData BookBook Global Vehicle Production and Sales Regional Vehicle Production and Sales History and Forecast Regional Vehicle Production and Sales by Model Regional Assembly Plant Maps Top 100 Global Suppliers Contents Global vehicle production and sales...............................................4-8 2005 Western Europe production and sales..........................................10-18 North America production and sales..........................................19-29 Global Japan production and sales .............30-37 India production and sales ..............39-40 Korea production and sales .............39-40 China production and sales..............39-40 Market Australia production and sales..........................................39-40 Argentina production and sales.............45 Brazil production and sales ....................45 Data Book Top 100 global suppliers...................46-50 Mary Raetz Anne Wright Curtis Dorota Kowalski, Debi Domby Senior Statistician Global Market Data Book Editor Researchers [email protected] [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Paul McVeigh, News Editor e-mail: [email protected] Irina Heiligensetzer, Production/Sales Support Tel: (49) 8153 907503 CZECH REPUBLIC: Lyle Frink, Tel: (49) 8153 907521 Fax: (49) 8153 907425 e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (420) 606-486729 e-mail: [email protected] Georgia Bootiman, Production Editor e-mail: [email protected] USA: 1155 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, MI 48207 Tel: (49) 8153 907511 SPAIN, PORTUGAL: Paulo Soares de Oliveira, Tony Merpi, Group Advertising Director e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (35) 1919-767-459 Larry Schlagheck, US Advertising Director www.automotivenewseurope.com Douglas A. Bolduc, Reporter e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (1) 313 446-6030 Fax: (1) 313 446-8030 Tel: (49) 8153 907504 Keith E. -

MX-Press (Newsletter of the Mazda MX-5 Club of WA Inc.)

www.mx5club.com.au Founded 1990 pressTHE BIMONTHLY MAGAZINE OF THE MAZDA MX-5 CLUB OF WA INC. Editing, design and production Simon Corston & Bob Sharpe Mazda Jan-Feb 2017 Club of Western Australia Inside 5 Humour Us 6 Coming Events 8 NZ Tiki Tour (Part I) 10 Event Photos 18 MX-5 Fan Fest 19 MX-5 Rocketeer Steve Harris - January 2017 President’s Report What do 477 MX-5s all gathered togeth- made at NatMeet and to make contact with for our cars, stating in a press interview for er in the same place look like? I hope that our exclusive WA representatives. Lyall had motoring.com.au “It makes me incredibly the photos in this copy of MX-press do full registered for motor sport, while Dave and proud that no matter where in the world I justice to the truly magnificent sight. Ken had gained photographer accreditation travel, the love for the MX-5 is always the This was the Mazda MX-5 FanFest held allowing them greater access; while John, same.” I think that we can all endorse that. on 21 January at Sandown in Melbourne to Carol and I just enjoyed the day. And what The weekend did not end there. With so give Australian MX-5 owners the opportu- a day it was. many interstate visitors, the Vic/Tas club nity to see and sign the one millionth MX-5 Club members enrolled in motor sport had organised a cruise (actually six cruises off the production line and also to see the had the track for most of the day (Lyall has with a common end point to accommo- RF model for the first time. -

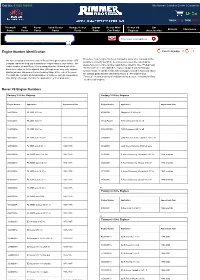

Engine Number Identification Rover V8 Engine Numbers Search by Part No. Or Description

Call Us: 01522 568000 My Account | Customer Service | Contact Us Items: 0 | Total £0.00 Triumph MG Rover Land Rover Range Rover Jaguar Rover Mini Rover V8 Car Brands Clearance Parts Parts Parts Parts Parts Parts Car Parts Engines Accessories Enter your email address Search By Part No. or Description Engine Number Identification Select Language ▼ ▼ Therefore, if your engine has been changed at some time, it should still be We have included a reference chart of Rover V8 engine numbers from 1970 possible to correctly identify it. To ensure you receive the correct parts, onwards, which will help you to identify the engine fitted to your vehicle. The please have your engine number ready before ordering. Note: "Pulsair" and engine number of most Rover V8s is stamped on the left hand side of the "Air Injection" are terms applied to engines equipped with Air Rail type block deck, adjacent to the dipstick tube, although some very early engines cylinder heads; ie cylinder heads with steel pipes located in holes just above had the number stamped on the bellhousing flange at the rear of the block. the exhaust ports (fitted to carb Range Rover & TR8 engines only). The chart also contains a brief description of features, such as compression "Detoxed" refers to a variety of emission control devices - including Air Rails ratio and gearbox type and also the approximate year of production. - fitted to carb engines. Rover V8 Engine Numbers Factory 3.5 Litre Engines Factory 3.9 Litre Engines Engine Number Application Approximate Year Engine Number Application -

Annual Report 2018/19 (PDF)

JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC Annual Report 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 1 Introduction THIS YEAR MARKED A SERIES OF HISTORIC MILESTONES FOR JAGUAR LAND ROVER: TEN YEARS OF TATA OWNERSHIP, DURING WHICH WE HAVE ACHIEVED RECORD GROWTH AND REALISED THE POTENTIAL RATAN TATA SAW IN OUR TWO ICONIC BRANDS; FIFTY YEARS OF THE EXTRAORDINARY JAGUAR XJ, BOASTING A LUXURY SALOON BLOODLINE UNLIKE ANY OTHER; AND SEVENTY YEARS SINCE THE FIRST LAND ROVER MOBILISED COMMUNITIES AROUND THE WORLD. TODAY, WE ARE TRANSFORMING FOR TOMORROW. OUR VISION IS A WORLD OF SUSTAINABLE, SMART MOBILITY: DESTINATION ZERO. WE ARE DRIVING TOWARDS A FUTURE OF ZERO EMISSIONS, ZERO ACCIDENTS AND ZERO CONGESTION – EVEN ZERO WASTE. WE SEEK CONSCIOUS REDUCTIONS, EMBRACING THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY AND GIVING BACK TO SOCIETY. TECHNOLOGIES ARE CHANGING BUT THE CORE INGREDIENTS OF JAGUAR LAND ROVER REMAIN THE SAME: RESPONSIBLE BUSINESS PRACTICES, CUTTING-EDGE INNOVATION AND OUTSTANDING PRODUCTS THAT OFFER OUR CUSTOMERS A COMPELLING COMBINATION OF THE BEST BRITISH DESIGN AND ENGINEERING INTEGRITY. CUSTOMERS ARE AT THE HEART OF EVERYTHING WE DO. WHETHER GOING ABOVE AND BEYOND WITH LAND ROVER, OR BEING FEARLESSLY CREATIVE WITH JAGUAR, WE WILL ALWAYS DELIVER EXPERIENCES THAT PEOPLE LOVE, FOR LIFE. The Red Arrows over Solihull at Land Rover’s 70th anniversary celebration 2 JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 STRATEGIC REPORT 3 Introduction CONTENTS FISCAL YEAR 2018/19 AT A GLANCE STRATEGIC REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 3 Introduction 98 Independent Auditor’s report to the members