In Transition: Artworks Between the Archive and the Exhibition Hall at the NGMA by Arnika Ahldag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Syllabus of Arts Education

SYLLABUS OF ARTS EDUCATION 2008 National Council of Educational Research and Training Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi - 110016 Contents Introduction Primary • Objectives • Content and Methods • Assessment Visual arts • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Theatre • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Music • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Dance • Upper Primary • Secondary • Higher Secondary Heritage Crafts • Higher Secondary Graphic Design • Higher Secondary Introduction The need to integrate art s education in the formal schooling of our students now requires urgent attention if we are to retain our unique cultural identity in all its diversity and richness. For decades now, the need to integrate arts in the education system has been repeatedly debated, discussed and recommended and yet, today we stand at a point in time when we face the danger of lo osing our unique cultural identity. One of the reasons for this is the growing distance between the arts and the people at large. Far from encouraging the pursuit of arts, our education system has steadily discouraged young students and creative minds from taking to the arts or at best, permits them to consider the arts to be ‘useful hobbies’ and ‘leisure activities’. Arts are therefore, tools for enhancing the prestige of the school on occasions like Independence Day, Founder’s Day, Annual Day or during an inspection of the school’s progress and working etc. Before or after that, the arts are abandoned for the better part of a child’s school life and the student is herded towards subjects that are perceived as being more worthy of attention. General awareness of the arts is also ebbing steadily among not just students, but their guardians, teachers and even among policy makers and educationalists. -

Artists' Statement on Growing Political and Religious Intolerance

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Artists' Statement on Growing Political and Religious Intolerance SAHMAT Vol. 50, Issue No. 44, 31 Oct, 2015 The artist community of India stands in firm solidarity with the actions of our writers who have relinquished awards and positions, and spoken up in protest against the alarming rise of intolerance in the country. We condemn and mourn the murders of MM Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare, rationalists and free thinkers whose voices have been silenced by rightwing dogmatists but whose “presence” must ignite our resistance to the conditions of hate being generated around us. The artist community of India stands in firm solidarity with the actions of our writers who have relinquished awards and positions, and spoken up in protest against the alarming rise of intolerance in the country. We condemn and mourn the murders of MM Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare, rationalists and free thinkers whose voices have been silenced by rightwing dogmatists but whose “presence” must ignite our resistance to the conditions of hate being generated around us. We will never forget the battle we fought for our pre-eminent artist MF Husain who was hounded out of the country and died in exile. We remember the rightwing invasion and dismantling of freedoms in one of the country’s best known art schools in Baroda. We witness the present government’s appointment of grossly unqualified persons to the FTII Society and its disregard of the ongoing strike by the students of this leading Institute. We see a writer like Perumal Murugan being intimidated into declaring his death as a writer, a matter of dire shame in any society. -

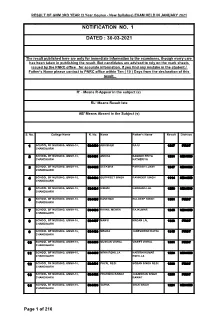

Notification No. 1 Dated : 30-03-2021

RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 30-03-2021 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject (s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent in the Subject (s) S. No. College Name R. No. Name Father's Name Result Division 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534480 ABHISHEK RAJU 1287 FIRST CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534481 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 1231 SECOND CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534482 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 1247 SECOND CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534483 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 1114 SECOND CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534484 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 1250 SECOND CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534485 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 1381 FIRST CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534486 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 1245 SECOND CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534487 MANSI MADAN LAL 1338 FIRST CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534488 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 1315 FIRST CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534489 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 1301 FIRST CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534490 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 1223 SECOND CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534491 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 1296 FIRST CHANDIGARH 13 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534492 PRATIBHA RAWAT JAGMOHAN SINGH 1266 FIRST CHANDIGARH RAWAT 14 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 534493 SAPNA SHER SINGH 1221 SECOND CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 216 RESULT OF GNM 3RD YEAR (3 Year Course - New Syllabus) EXAM HELD IN JANUARY 2021 S. -

AWARDS AWARDS Awards & Recognition- April Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Lyricist & Director Sreekumaran Thampi Has Been Organization‟S (UNESCO)

AWARDS AWARDS Awards & Recognition- April Nations Educational, Scientific & Cultural Lyricist & director Sreekumaran Thampi has been Organization‟s (UNESCO). selected for the J.C. Daniel Award, the Kerala The Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) government‟s highest honour for lifetime contribution is awarded the National Intellectual Property (IP) to Malayalam cinema. The award comprises of Rs5 Award 2018 in the category “Top R&D Institution / lakh & a citation. Organization for Patents & Commercialization”. Dr Bollywood actor Anushka Sharma will be awarded the Girish Sahni, DG, CSIR & Secretary, DSIR received the Dadasaheb Phalke Excellence Award for her award at the hands of Mr. Suresh Prabhu, Minister of successful movies as a producer. Commerce & Industry. Veteran Hindi film actor Shri Vinod Khanna was Bollywood actors Bhumi Pednekar, Sonam Kapoor & awarded the Dadasaheb Phalke Award for his Akshay Kumar bagged the best actress & best actor contribution to Indian Cinema. This was announced awards respectively at the Dadasaheb Phalke awards, during the 65th National Film Awards. given by Dadasaheb Phalke Film Foundation, held in Veteran Bollywood actor Dharmendra will be Mumbai. Manisha Koirala won the „Most Versatile conferred with the prestigious Raj Kapoor Lifetime Actress‟ award. Veteran actor-director Rakesh Roshan Achievement & filmmaker Rajkumar Hirani with Raj was given the lifetime achievement award for his Kapoor Special Contribution awards. Maharashtra contribution to the industry as an actor, producer & a Culture Minister Vinod Tawde announced the names director. of the winners. Gujarati poet, playwright & academic Sitanshu Kolkata-based Bandhan Bank Ltd became one of the Yashaschandra was selected for 2017 Saraswati top 50 most valuable publicly traded firms in India. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Syed Haider Raza Painter

Syed Haider Raza Painter S.H. Raza was born as Syed Haider Raza in the year 1922, in the state of Madhya Pradesh. One of the most distinguished artists of the Indian subcontinent, Raza has been settled in France since 1950. However, his ties with India remain as strong as ever. The paintings of Syed Haider Raza have been done mainly in oil or acrylic and have a very heavy usage of color. His wife is a French artist, Janine Mongillat. Know more about the biography and life history of S.H. Raza with this article: Raza received his formal training in painting at the Nagpur School of Art (Nagpur) and Sir J. J. School of Art (Mumbai). During his stay at the Sir J.J. School, he became a member of Progressive Artist Group. At that time, SH Raza experimented with the Western Modernism, which was moving away from expressionism and towards abstraction. Thereafter, he shifted to France to pursue his studies at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts of Paris. The paintings of Syed Haider Raza in the 1940s and 1950s revolved mainly around landscapes. His Style The paintings of S.H. Raza revolve mainly around nature and its various faucets. His paintings have evolved from being purely expressionist landscapes to abstract ones. He believes the Bindu (dot) to be the center of creation and existence and his works reflect this particular thinking. Even though the vibrancy of his paintings has become subtle, the dynamism remains as alive as ever. Achievements A painting by S.H. Raza was reportedly sold for US $1.4 million at an auction held in December 2006. -

Result of Gnm 1St Year Exam Held in December - 2018

RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 NOTIFICATION NO. 1 DATED : 31-05-2019 The result published here are only for immediate information to the examinees, though every care has been taken in publishing the result. But candidates are advised to rely on the mark sheets issued by the PNRC office for accurate information. If you find any mistake in the student / Father's Name please contact to PNRC office within Ten ( 10 ) Days from the declaration of this result. R' - Means R-Appear in the subject,(s) RL' Means Result late AB' Means Absent S. College Name Roll No Name Father Name Result No. 1 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483001 ABHISHEK RAJU 354 CHANDIGARH 2 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483002 ANKITA BAUDDH PRIYA 315 CHANDIGARH KATHERIYA 3 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483003 DEEKSHA PARKASH LUXMI 334 CHANDIGARH 4 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483004 GURPREET SINGH RAVINDER SINGH 312 CHANDIGARH 5 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483005 HIMANI HARBANS LAL 332 CHANDIGARH 6 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483006 KANCHAN KULDEEP SINGH 366 CHANDIGARH 7 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483007 KHANIL MEHRA RAJKUMAR 328 CHANDIGARH 8 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483008 MANSI MADAN LAL 356 CHANDIGARH 9 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483009 MEGHA JANESHWAR DAYAL 347 CHANDIGARH 10 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483010 MUSKAN VISHAL VINEET VISHAL 355 CHANDIGARH 11 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483011 NEHA ROHILLA NARESH KUMAR 324 CHANDIGARH ROHILLA 12 SCHOOL OF NURSING, GMSH-16, 483012 PAYAL NEGI SOBAN SINGH NEGI 346 CHANDIGARH Page 1 of 304 RESULT OF GNM 1ST YEAR EXAM HELD IN DECEMBER - 2018 S. -

BE CAPTIVATED:The Founders and the Cutting Edge of South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art at Christie's in June

For Immediate Release Tuesday, 26 May 2009 Contact: Hannah Schmidt 020 7389 2964 [email protected] BE CAPTIVATED: The Founders and The Cutting Edge of South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art at Christie’s in June South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art Wednesday, 10 June 2009 at 2.00pm London – Christie’s sale of South Asian Modern and Contemporary Art on Wednesday 10 June 2009 showcases a wide range of captivating works by the leading artists of 20th and 21st century South Asia, primarily India and Pakistan. From celebrated masters of the Progressive Artists Group through to the biggest names in contemporary art, attractive estimates cross the spectrum of artists, styles and media with estimates ranging from £1,000 to £600,000. The sale has is expected to realise in excess of £2million. Highlights range from Ragamala Series, 1960 by Maqbool Fida Husain (b.1915) (estimate: £400,000- 600,000) illustrated top left and Untitled, circa 1966-67 by Tyeb Mehta (b.1925) (estimate: £80,000-120,000), to Red Carpet – 4, 2007-08 by Rashid Rana (b.1968) (estimate: £135,000-200,000) and Leap of Faith, 2005- 2006 by Subodh Gupta (b.1964) (estimate: £70,000-100,000) illustrated top right. Many works are from private collections and come fresh to the market. Yamini Mehta, Christie’s Senior Specialist, South Asian Modern + Contemporary Art, London: The auction comes at a precipitous time as increasingly, international institutions are showcasing Indian and Pakistani art with several key exhibitions on the horizon throughout Europe. June 2009 coincides with Venice Biennale, which features both Indian and Pakistani artists while forthcoming exhibitions are in development at the Whitechapel Gallery and the Saatchi Gallery in London.” MODERNISM: The top lot of the sale is a large panoramic scene depicting Indian musicians, Ragamala Series, 1960, by Maqbool Fida Husain (b.1915) (estimate: £400,000-600,000) illustrated top left. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

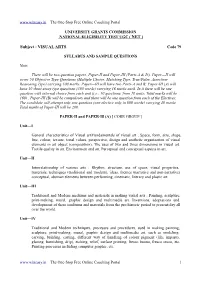

Subject : VISUAL ARTS Code 79

www.wineasy.in – The One-Stop Free Online Coaching Portal UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION NATIONAL ELIGIBILITY TEST UGC ( NET ) Subject : VISUAL ARTS Code 79 SYLLABUS AND SAMPLE QUESTIONS Note: There will be two question papers, Paper-II and Paper-III (Parts-A & I3). Paper—II will cover 50 Objective Type Questions (Multiple Choice, Matching Type, True/False, Assertion- Reasoning Type) carrying 100 marks. Paper—III will have two Parts-A and B; Paper-III (A) will have 10 short essay type questions (300 words) carrying 16 marks each. In it there will be one question with internal choice from each unit (i.e., 10 questions. from 10 units; Total marks will be 160) . Paper-III (B) will be compulsory and there will be one question from each of the Electives. The candidate will attempt only one question (one elective only in 800 words) carrying 40 marks. Total marks of Paper-III will be 200. PAPER-II and PAPER-Ill (A) [ CORE GROUP ] Unit—I General characteristics of Visual art/Fundamentals of visual art : Space, form, size, shape, line, colour, texture, tonal values, perspective, design and aesthetic organization of visual elements in art object (composition). The uses of two and three dimensions in visual art. Tactile quality in art. Environment and art. Perceptual and conceptual aspects in art. Unit—II Interrelationship of various arts : Rhythm, structure, use of space, visual properties. materials, techniques (traditional and modern), ideas, themes (narrative and non-narrative) conceptual, abstract elements between performing, cinematic, literary and plastic art. Unit—III Traditional and Modern mediums and materials in making visual arts : Painting, sculpture, print-making, mural, graphic design and multimedia art.