Occupations in Rural Communities in the Heart of England from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

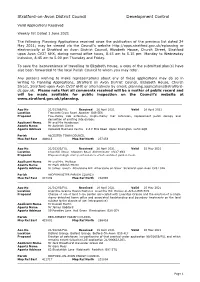

Weekly List Dated 1 June 2021

Stratford-on-Avon District Council Development Control Valid Applications Received Weekly list Dated 1 June 2021 The following Planning Applications received since the publication of the previous list dated 24 May 2021; may be viewed via the Council’s website http://apps.stratford.gov.uk/eplanning or electronically at Stratford on Avon District Council, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford upon Avon CV37 6HX, during normal office hours, 8.45 am to 5.15 pm Monday to Wednesday inclusive, 8.45 am to 5.00 pm Thursday and Friday. To save the inconvenience of travelling to Elizabeth House, a copy of the submitted plan(s) have also been forwarded to the local Parish Council to whom you may refer. Any persons wishing to make representations about any of these applications may do so in writing to Planning Applications, Stratford on Avon District Council, Elizabeth House, Church Street, Stratford upon Avon CV37 6HX or alternatively by email; planning.applications@stratford- dc.gov.uk. Please note that all comments received will be a matter of public record and will be made available for public inspection on the Council’s website at www.stratford.gov.uk/planning. _____________________________________________________________________________ App No 21/01389/FUL Received 26 April 2021 Valid 26 April 2021 Location Tremarta Cross Road Alcester B49 5EX Proposal Two-storey side extension, single-storey rear extension, replacement porch canopy and demolition of existing side garage. Applicant Name Mr and Mrs Henderson Agents Name Mr Ashleigh Clarke Agents Address Cotswold Business Centre 2 A P Ellis Road Upper Rissington GL54 2QB Parish ALCESTER TOWN COUNCIL Map Ref East 408613 Map Ref North 257453 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ App No 21/01393/FUL Received 26 April 2021 Valid 25 May 2021 Location Churchill House Shipston Road Alderminster CV37 8NX Proposal Proposed single storey extension to create outdoor garden room Applicant Name Mr and Mrs. -

Harvington Conservation Area

Harvington Conservation Area Harvington The Harvington Area Appraisal and Management Proposals were adopted by Wychavon District Council as a document for planning purposes. Minute 53 of the Executive Board meeting of 25 November 2015 refers. Wychavon District Council Planning Services Civic Centre Queen Elizabeth Drive Pershore Worcestershire WR10 1PT Tel. 01386 565000 www.wychavon.gov.uk 1 Harvington 1 Part 1 APPRAISAL 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Purpose of a Conservation Area Appraisal Planning Policy Framework 2 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST 3 3 ASSESSING SPECIAL INTEREST 4 Location & Landscape Setting Historical Development & Archaeology Plan Form Spaces Key Views & Vistas 4 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 14 General Buildings Materials Local Details Boundaries Natural Environment Negative Features & Neutral Areas Threats 5 ISSUES 28 Appraisal Map Part 2 MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 31 1 INTRODUCTION 2 MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 3 DESIGN CODES 4 ARTICLE 4(2) DIRECTIONS APPENDIX 01 Statement of Community Involvement APPENDIX 02 Sources & Further Information 1 Harvington 2 Part 1 …………………………………… Planning Policy Framework CONSERVATION AREA 1.4 This appraisal should be read in APPRAISAL conjunction with the Development Plan, which comprises the saved policies of the 1 INTRODUCTION Wychavon District Local Plan (June 2006) and national planning policy as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework Purpose of a Conservation Area (March 2012) specifically Wychavon Appraisal District Local Plan Policy Env12 which is 1.1 intended to ensure that development A conservation area is an “area of special preserves or enhances the character or architectural or historic interest, the appearance of conservation areas. character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance” National Planning Policy Framework 126 – (Planning (Listed Buildings and 141 sets out the Governments planning Conservation Areas) Act 1990, Section policy on conserving and enhancing the 69). -

468 KB Adobe Acrobat Document, Opens in A

Campden & District Historical and Archæological Society Regd. Charity No. 1034379 NOTES & QUERIES NOTES & QUERIES Volume VI: No. 1 Gratis Autumn 2008 ISSN 1351-2153 Contents Page From the Editor 1 Letters to the Editor 2 Maye E. Bruce Andrew Davenport 3 Lion Cottage, Broad Campden Olivia Amphlett 6 Sir Thomas Phillipps 1792-1872: Bibliophile David Cotterell 7 Rutland & Chipping Campden: an unexplained connection Tim Clough 9 Putting their hands to the Plough, part II Margaret Fisher 13 & Pearl Mitchell Before The Guild: Rennie Mackintosh Jill Wilson 15 ‘The Finest Street Left In England’ Carol Jackson 16 Christopher Whitfield 1902-1967 John Taplin 18 From The Editor As I start to edit this issue, I have just heard of the sad and unexpected death on 26th July after a very short illness, of Felicity Ashbee, aged 95, a daughter of Charles and Janet Ashbee. Her funeral was held on 6th August and there is to be a Memorial Tribute to her on 2nd October at the Art Workers Guild in London. Felicity has been the authority on her parents’ lives for many years now and her Obituary in the Independent described her as ‘probably the last close link with the inner circle of extraordinary creative talents fostered or inspired by William Morris’ … her death ‘marks its [the Arts & Crafts movement] formal and final passing’. This first issue of Volume Number VI is a bumper issue full of connections. John Taplin, Andrew Davenport and Tim Clough (Editor of Rutland Local History & Record Society), after their initial queries to the Archive Room, all sent articles on their researches; the pieces on Maye Bruce and Thomas Phillipps are connected with new publications; there is an ‘earthy’ connection between with the Plough, Rutland and Bruce researches and the Phillipps and Whitfield articles both have Shakespeare connections. -

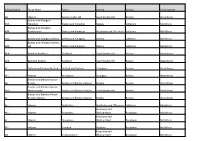

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

Warwickshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects West Midlands WARWICKSHIRE North Warwickshire 3/1548 (E.44.L006) SP 32359706 CV9 1RS 30 THE SPINNEY, MANCETTER Mancetter, 30 the Spinney Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 3pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The site lies in an area where well preserved remains of Watling Street Roman Road were exposed in the 1970's. No Roman finds were noted during the recent developments and imported material suggested that the original top soil and any archaeological layers were previously removed. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number:386, 420 3/1549 (E.44.L003) SP 32769473 CV10 0TG HARTSHILL, LAND ADJACENT TO 49 GRANGE ROAD Hartshill, Land Adjacent to 49 Grange Road Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 3pp, figs, Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services No finds or features of archaeological significance were recorded. [Au(abr)] 3/1550 (E.44.L042) SP 17609820 B78 2AS MIDDLETON, HOPWOOD, CHURCH LANE Middleton, Hopwood, Church Lane Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 4pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The cottage itself was brick built, with three bays and appeared to date from the late 18th century or early 19th century. A number of timber beams withiin the house were re-used and may be from an earlier cottage on the same site. The watching brief revealed a former brick wall and fragments of 17th/18th century pottery. [Au(abr)] Archaeological periods represented: PM 3/1551 (E.44.L007) SP 32009650 CV9 1NL THE BARN, QUARRY LANE, MANCETTER Mancetter, the Barn, Quarry Lane Coutts, C Warwick : Warwickshire Museum Field Services, 2003, 2pp, figs Work undertaken by: Warwickshire Museum Field Services The excavations uncovered hand made roof tile fragments and fleck of charcoal in the natural soil. -

Records Indexes Tithe Apportionment and Plans Handlist

Records Service Records Indexes Tithe Apportionment and Plans handlist The Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 replaced the ancient system of payment of tithes in kind with monetary payments. As part of the valuation process which was undertaken by the Tithe Commissioners a series of surveys were carried out, part of the results of which are the Tithe Maps and Apportionments. An Apportionment is the principal record of the commutation of tithes in a parish or area. Strictly speaking the apportionment and map together constitute a single document, but have been separated to facilitate use and storage. The standard form of an Apportionment contains columns for the name(s) of the landowners and occupier(s); the numbers, acreage, name or description, and state of cultivation of each tithe area; the amount of rent charge payable, and the name(s) of the tithe-owner(s). Tithe maps vary greatly in scale, accuracy and size. The initial intent was to produce maps of the highest possible quality, but the expense (incurred by the landowners) led to the provision that the accuracy of the maps would be testified to by the seal of the commissioners, and only maps of suitable quality would be so sealed. In the end, about one sixth of the maps had seals. A map was produced for each "tithe district", that is, one region in which tithes were paid as a unit. These were often distinct from parishes or townships. Areas in which tithes had already been commutated were not mapped, so that coverage varied widely from county to county. -

Council Land and Building Assets

STRATFORD ON AVON DISTRICT COUNCIL - LAND AND BUILDING ASSETS - JANUARY 2017 Ownership No Address e Property Refere Easting Northing Title: Freehold/Leasehold Property Type User ADMINGTON 1 Land Adj Greenways Admington Shipston-on-Stour Warwickshire 010023753344 420150 246224 FREEHOLD LAND Licence ALCESTER 1 Local Nature Reserve Land Off Ragley Mill Lane Alcester Warwickshire 010023753356 408678 258011 FREEHOLD LAND Leasehold ALCESTER 2 Land At Ropewalk Ropewalk Alcester Warwickshire 010023753357 408820 257636 FREEHOLD LAND Licence Land (2) The Corner St Faiths Road And Off Gunnings Occupied by Local ALCESTER 3 010023753351 409290 257893 FREEHOLD LAND Road Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 4 Bulls Head Yard Public Car Park Bulls Head Yard Alcester Warwickshire 010023389962 408909 257445 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 5 Bleachfield Street Car Park Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753358 408862 257237 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 6 Gunnings Bridge Car Park School Road Alcester Warwickshire 010023753352 409092 257679 LEASEHOLD LAND Authority LAND AND ALCESTER 7 Abbeyfield Society Henley Street Alcester Warwickshire B49 5QY 100070204205 409131 257601 FREEHOLD Leasehold BUILDINGS Kinwarton Farm Road Public Open Space Kinwarton Farm Occupied by Local ALCESTER 8 010023753360 409408 258504 FREEHOLD LAND Road Kinwarton Alcester Warwickshire Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 9 Land (2) Bleachfield Street Bleachfield Street Alcester Warwickshire 010023753361 408918 256858 FREEHOLD LAND Authority Occupied by Local ALCESTER 10 Springfield Road P.O.S. -

Clifford Chambers & Milcote Neighbourhood Plan Submission

ambers Ch & d M r il fo c f o i l t e C Neighbourhood Plan 2011 - 2031 Submission Document August 2019 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. A History of Clifford Chambers & Milcote 9 3. A Future Vision 10 4. Housing 14 H1 Housing Growth 14 H2 Local Housing Need 18 H3 Live Work Units 20 H4 Use of Garden Land 21 5. Natural Environment 22 NE1 Flood Risk and Surface Water Drainage 22 NE2 Protection of Valued Landscapes 25 NE3 Nature Conservation 29 NE4 Maintaining ‘Dark Skies’ 30 6. Local Community 32 LC1 Designated Heritage Assets 32 LC2 Designated Green Spaces 34 LC3 Neighbourhood Area Character 36 LC4 Promoting High Speed Broadband 38 7. Traffic and Transport 39 TT1 Parking 39 TT2 Walking and Cycling 40 TT3 Highway Safety 41 1 Clifford Chambers & Milcote Neighbourhood Plan - Submission August 2019 List of Figures & Appendices List of Figures 1. Clifford Chambers & Milcote Neighbourhood Area 4 2. Village Built-up Area Boundary 16 3. Reserve Housing Allocation 17 4(a). Environment Agency Flood Plain Map 23 4(b). River Stour in flood 24 5. Map of historical flooding 24 6(a). Mapped view across fields to Martin’s Hill 26 6(b). A view across fields to Martin’s Hill 26 7(a). Mapped view of Oak trees on the western edge of the Village from Martin’s Hill 27 7(b). View of Oak trees on the western edge of the Village from Martin’s Hill 27 7(c). Oak trees on the western edge of the Village 28 8. -

Bourton Times

COTSWOLD TIMES BOURTON TIMES AUGUST 2015 ISSUE 65 Fabulous Fare at FEASTIVAL PAGES 10-11 #CarryMeHomeKate PAGES 14-15 WHAT’S ON? – PAGES 27-36 Events Diary PAGE 32 PHOTO COMPETITION PAGES 33-43 PLUS – Your local sports reports, schools and community news 1 • Under New Management • Recently refurbished • Beautiful gardens • Real Ales • Excellent Food 01451 850344 Halfway House Kineton Guiting Power Cheltenham GL54 5UG Discover beautiful Batsford Arboretum for yourself, or with friends and family this August The BIG Batsford Make a day of it! Visit… Bug Hunt . st st 1 to 31 August, 10am - 5pm Find the creepy crawlies hidden around the arboretum, mark The Applestore their location on our map Beautiful, shabby chic using the stickers provided Plant Centre interior ideas – stockists of and pick up a goodie bag! If you've seen something you love in Annie Sloan Chalk Paint™, furniture, soft furnishings the Arboretum, chances are you'll The Bug Hunt costs £2.50 and a host of gifts. find it – or something similar – in Stock changes almost daily! per child (plus arboretum the Plant Centre, so don't forget to entrance fee) and all children pay Sylvia and her team a visit must be accompanied by an during your trip to Batsford. Our adult (arboretum entrance fee wide range of beautiful herbaceous also applies). plants are guaranteed to bring colour and interest to your garden No booking required – Garden Terrace Cafe year in and year out. just turn up and enjoy! Eat out on our lovely terrace Batsford is open every day 9am 5pm. -

Warwickshire Industrial Archaeology Society

WARWICKSHIRE IndustrialW ArchaeologyI SociASety NUMBER 31 June 2008 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER THIS ISSUE it was felt would do nothing to web site, and Internet access further these aims and might becoming more commonplace ¢ Meeting Reports detract from them, as if the amongst the Society membership, current four page layout were what might be the feelings of ¢ From The Editor retained, images would reduce the members be towards stopping the space available for text and practice of posting copies to possibly compromise the meeting those unable to collect them? ¢ Bridges Under Threat reports. Does this represent a conflict This does not mean that with the main stated aim of ¢ Meetings Programme images will never appear in the publishing a Newsletter, namely Newsletter. If all goes to plan, that of making all members feel this edition will be something of a included in the activities of the FROM THE EDITOR milestone since it will be the first Society? y editorial in the to contain an illustration; a Mark Abbott March 2008 edition of diagram appending the report of Mthis Newsletter the May meeting. Hopefully, PROGRAMME concerning possible changes to its similar illustrations will be format brought an unexpected possible in future editions, where Programme. number of offers of practical appropriate and available, as the The programme through to help. These included the offer of technology required to reproduce December 2008 is as follows: a second hand A3 laser printer at them is now quite September 11th a very attractive price; so straightforward. The inclusion of Mr. Lawrence Ince: attractive as to be almost too photographs is not entirely ruled Engine-Building at Boulton and good an opportunity to ignore. -

Industrial/ Open Storage Land 2 Acres (8,100 Sq.M) to LET Haunchwood Park, Bermuda Road, Nuneaton, CV10 7QG

Industrial/ Open Storage Land 2 Acres (8,100 sq.m) TO LET Haunchwood Park, Bermuda Road, Nuneaton, CV10 7QG PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS • 2 acres storage to let • Secure palisade fence • Sub divisible from 1 acre • Close to motorway network • Flexible lease options available • Design and build option may be available LOCATION BERMUDA CONNECTION Nuneaton oers a strategic location for distribution Bermuda Connection is a proposed scheme focused occupiers in the West Midlands being conveniently on tackling congestion in and around West Nuneaton located some four miles North of the M6 motorway. The by creating a direct 1.3mile highway link between West M6 can be accessed by the A444 at Junction 3 of the Nuneaton and Griff Roundabout.More details available M6. Alternatively, the M69 motorway at Hinckley can be at www.warwickshire.gov.uk/bermudaconnection. accessed at Junction 1 for access to the motorway At the time of publication of these particulars a final network in a northerly direction. decision has yet to be taken regarding the implementation of the Bermuda Connection scheme DESCRIPTION This 2 acre site consist of cleared open storage land with a concrete base to part and a secure palisade fence. B U L L HEATH END ROAD R IN RENT G B E R M £60,000 per annum U D A R GEORGE ELIOT O HOSPITAL A SERVICES D A444 All mains services connected. TENURE The site is available on a new lease on flexible terms as whole or from 1 acre. Alternatively design and build proposals available on request. A444 M42 A444 A38 J8 A5 Nuneaton M6 BIRMINGHAM M69 M1 J7 Bedworth M6 A5 J6 A45 J2 A34 A41 M6 Solihull COVENTRY A435 J19 A452 A45 Rugby M1 M42 A46 A45 J3a A445 M45 M40 J17 A429 Redditch A423 Leamington Spa A45 A435 Warwick Daventry J15 VAT ROAD LINKS Bromwich Hardy stipulate that prices are quoted M6 Junction 3 5.1 miles exclusive of V.A.T.