Rediscovered, a 'Lost' Meroitic Object: the Hamadab Lion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

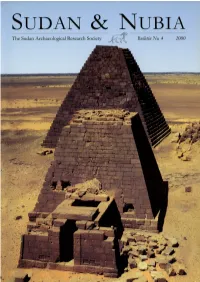

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Seleima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Archaeological Park Or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage At

Égypte/Monde arabe 5-6 | 2009 Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan Parc archéologique ou « Disneyland » ? Conflits d’intérêts sur le patrimoine à Naqa au Soudan Ida Dyrkorn Heierland Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 DOI: 10.4000/ema.2908 ISSN: 2090-7273 Publisher CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Printed version Date of publication: 22 December 2009 Number of pages: 355-380 ISBN: 2-905838-43-4 ISSN: 1110-5097 Electronic reference Ida Dyrkorn Heierland, « Archaeological Park or “Disneyland”? Conflicting Interests on Heritage at Naqa in Sudan », Égypte/Monde arabe [Online], Troisième série, Pratiques du Patrimoine en Égypte et au Soudan, Online since 31 December 2010, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/ema/2908 ; DOI : 10.4000/ema.2908 © Tous droits réservés IDA DYRKORN HEIERLAND ABSTRACT / RÉSUMÉ ARCHAEOLOGICAL PARK OR “DISNEYLAND”? CONFLICTING INTERESTS ON HERITAGE AT NAQA IN SUDAN The article explores agencies and interests on different levels of scale permeat- ing the constituting, management and use of Sudan’s archaeological heritage today as seen through the case of Naqa. Securing the position of “unique” and “unspoiled sites”, the archaeological community and Sudanese museum staff seem to emphasize the archaeological heritage as an important means for constructing a national identity among Sudanese in general. The government, on the other hand, is mainly concerned with the World Heritage nomination as a possible way to promote Sudan’s global reputation and accelerate the economic exploitation of the most prominent archaeo- logical sites. -

Abu Simbel Solar Alignment 1

Abu Simbel Solar Alignment 1 Abu Simbel was built by Pharaoh Rameses II between 1279 and 1213 B.C to celebrate his domination of Nubia, and his piety to the gods, principally Amun-Re, Ra- Horakhty and Ptah, as well as his own deification. It is located 250 kilometers southeast of the city of Aswan. The original temple was positioned on the bank of the Nile, but it was raised up 300 meters by an international relocation project supported by UNESDO. This mammoth engineering effort was undertaken between 1964 and 1968 to prevent the flooding of the temple by the rising waters of Lake Nasser caused by the new Aswan High Dam. The satellite photo above, and on the next page, shows the entrance walkway ramp, and the area on the face of the cliff where the four giant statues of Ramses II are positioned. The interior of the temple extends to the left of the statuary and is hidden beneath the huge man-made berm to the left of the photograph. The 'Visitor Center' buildings can be seen as the three squares near the left-hand edge of the photo. The horizontal line in the upper right corner represents a distance of 50 meters, and the circle indicates the major compass directions clockwise from the top (north) as east, south and west. The interior of the temple is inside the sandstone cliff in the form of a man- made cave cut out of the rock. It consists of a series of halls and rooms extending back a total of 56 meters (185 feet) from the entrance. -

The Secrets of Egypt & the Nile

the secrets of egypt & the nile 2021 - 2022 Dear Valued Guest, Egypt has captured the world’s imagination and continues to make an extraordinary impression on those who visit; and beginning in September 2021, we are delighted to take you there. While traveling along Egypt’s Nile River, you’ll be treated to a connoisseur’s discovery of this ancient civilization as only AmaWaterways can provide—with an unparalleled river cruise and land adventure that includes exquisite cuisine, beautiful accommodations, authentic excursions and extraordinary service. Your journey along the world’s longest river on board our spectacular, newly designed AmaDahlia will take you to some of Egypt’s most iconic sites. Discover ancient splendors such as the Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, the beguiling Temple of Luxor and the mystifying Valley of the Kings and Queens, along with exclusive access to the Tomb of Queen Nefertari. While in Cairo, you’ll stay at the 5-star Four Seasons at The First Residence, an oasis in the middle of the city, where each day, you’ll experience some of the world’s most astonishing antiquities. Come face to face with King Tut’s priceless discoveries at the Egyptian Museum, as well as the Great Sphinx and the three Pyramids of Giza, the last surviving of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; and gain private access to Cairo’s Abdeen Presidential Palace. This mesmerizing destination has entranced archaeologists and historians for generations and inspired its own field of study—Egyptology. Now it’s time for you to be entranced. We look forward to sharing Egypt with you. -

Online Journal in Public Archaeology

ISSN: 2171-6315 Volume 3 - 2013 Editor: Jaime Almansa Sánchez www.arqueologiapublica.es AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology is edited by JAS Arqueología S.L.U. AP: Online Journal in Public Archaeology Volume 3 - 2013 p. 46-73 Rescue Archaeology and Spanish Journalism: The Abu Simbel Operation Salomé ZURINAGA FERNÁNDEZ-TORIBIO Archaeologist and Museologist “The formula of journalism is: going, seeing, listening, recording and recounting.” — Enrique Meneses Abstract Building Aswan Dam brought an unprecedented campaign to rescue all the affected archaeological sites in the region. Among them, Abu Simbel, one of the Egyptian icons, whose relocation was minutely followed by the Spanish press. This paper analyzes this coverage and its impact in Spain, one of the participant countries. Keywords Abu Simbel, Journalism, Spain, Rescue Archaeology, Egypt The origin of the relocation and ethical-technical problems Since the formation of UNESCO in 1945, the organisation had never received a request such as the one they did in 1959, when the decision to build the Aswan High Dam (Saad el Aali)—first planned five years prior—was passed, creating the artificial Lake Nasser in Upper Egypt. This would lead to the spectacular International Monuments Rescue Campaign of Nubia that was completed on 10 March 1980. It was through the interest of a Frenchwoman named Christiane Desroches Noblecourt and UNESCO—with the international institution asking her for a complete listing of the temples and monuments that were to be submerged—as well as the establishment of the Documentation Centre in Cairo that the transfer was made possible. -

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

DISCOVER EGYPT Including Alexandria • December 1-14, 2021

2021 Planetary Society Adventures DISCOVER EGYPT Including Alexandria • December 1-14, 2021 Including the knowledge and use of astronomy in Ancient Egypt! Dear Travelers: The expedition offers an excellent Join us!... as we discover the introduction to astronomy and life extraordinary antiquities and of ancient Egypt and to the ultimate colossal monuments of Egypt, monuments of the Old Kingdom, the December 1-14, 2021. Great Pyramids and Sphinx! It is a great time to go to Egypt as Discover the great stone ramparts the world reawakens after the of the Temple of Ramses II at Abu COVID-19 crisis. Egypt is simply Simbel, built during the New not to be missed. Kingdom, on the Abu Simbel extension. This program will include exciting recent discoveries in Egypt in The trip will be led by an excellent addition to the wonders of the Egyptologist guide, Amr Salem, and pyramids and astronomy in ancient an Egyptologist scholar, Dr. Bojana Egypt. Visits will include the Mojsov fabulous new Alexandria Library Join us!... for a treasured holiday (once the site of the greatest library in Egypt! in antiquity) and the new Alexandria National Museum which includes artifacts from Cleopatra’s Palace beneath the waters of Alexandria Harbor. Mediterranean Sea Alexandria Cairo Suez Giza Bawiti a y i ar is Bah s Oa Hurghada F arafra O asis Valley of Red the Kings Luxor Sea Esna Edfu Aswan EGYPT Lake Nasser Abu Simbel on the edge of the Nile Delta en route. We will first visit the COSTS & CONDITIONS Alexandria National Museum, to see recent discoveries from excavations in the city and its ancient harbors. -

Egypt: the Royal Tour | October 24 – November 6, 2021 Optional Pre-Trip Extensions: Alexandria, October 21 – 24 Optional Post-Trip Extension: Petra, November 6 - 10

HOUSTON MUSEUM OF NATURAL SCIENCE Egypt: The Royal Tour | October 24 – November 6, 2021 Optional Pre-Trip Extensions: Alexandria, October 21 – 24 Optional Post-Trip Extension: Petra, November 6 - 10 Join the Houston Museum of Natural Science on a journey of a lifetime to tour the magical sites of ancient Egypt. Our Royal Tour includes the must-see monuments, temples and tombs necessary for a quintessential trip to Egypt, plus locations with restricted access. We will begin in Aswan near the infamous cataracts of the River Nile. After visiting Elephantine Island and the Isle of Philae, we will experience Nubian history and culture and the colossal temples of Ramses II and Queen Nefertari at Abu Simbel. Our three-night Nile cruise will stop at the intriguing sites of Kom Ombo, Edfu and Esna on the way to Luxor. We will spend a few days in Egypt 2021: The Royal Tour Luxor to enjoy the Temples of $8,880 HMNS Members Early Bird Luxor and Karnak, the Valley of $9,130 HMNS Members per person the Kings, Queens and Nobles $9,300 non-members per person and the massive Temple of $1,090 single supplement Hatshepsut. Optional Alexandria Extension In Cairo we will enjoy the $1,350 per person double occupancy historic markets and neighborhoods of the vibrant modern city. $550 single supplement Outside of Cairo we will visit the Red Pyramid and Bent Pyramid in Dahshur Optional Petra Extension and the Step Pyramid in Saqqara, the oldest stone-built complex in the $2,630 per person double occupancy world. Our hotel has spectacular views of the Giza plateau where we will $850 single supplement receive the royal treatment of special admittance to stand in front of the Registration Requirements (p.