Urban Development Policy for Karnataka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Multiplicity of Phytoplankton Diversity in Tungabhadra River Near Harihar, Karnataka (India)

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2015) 4(2): 1077-1085 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 4 Number 2 (2015) pp. 1077-1085 http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article Multiplicity of phytoplankton diversity in Tungabhadra River near Harihar, Karnataka (India) B. Suresh* Civil Engineering/Environmental Science and Technology Study Centre, Bapuji Institute of Engineering and Technology, Davangere-577 004, Karnataka, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Water is one of the most important precious natural resources required essentially for the survival and health of living organisms. Tungabhadra River is an important tributary of Krishna. It has a drainage area of 71,417 sq km out of which 57,671 sq. km area lies in the state of Karnataka. The study was conducted to measure its various physico-chemical and bacteriological parameters including levels of algal K eywo rd s community. Pollution in water bodies may indicate the environment of algal nutrients in water. They may also function as indicators of pollution. The present Phytoplankton, investigation is an attempt to know the pollution load through algal indicators in multiplicity, Tungabhadra river of Karnataka near Harihar town. The study has been conducted Tungabhadra from May 2008 to April 2009. The tolerant genera and species of four groups of river. algae namely, Chlorophyceae, Bacilleriophyceae, Cyanaophyceae and Euglenophyceae indicate that total algal population is 17,715 in station No. S3, which has the influence of industrial pollution by Harihar Polyfibre and Grasim industry situated on the bank of the river which are discharging its treated effluent to this river. -

Harihara Taluk Is Situated on the Banks of Tungabhadra River

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES HARIHAR TALUK, DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA दवक्षण पविमी क्षेत्र, बℂगलोर South Western Region, Bengaluru AQUIFER MANAGEMENT PLAN OF HARIHAR TALUK, DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE CONTENTS Sl.No. Title PageNos. 1 Salient Information 1 2 Aquifer Disposition 7 3 Ground Water Resource, Extraction, 10 Contamination and other Issues 4 Ground Water Resource Enhancement 16 5 Demand Side Interventions 17 AQUIFER MANAGEMENT PLAN OF HARIHAR TALUK, DAVANAGERE DISTRICT, KARNATAKA STATE 1.0 Salient information Taluk name: HARIHAR District: Davanagere; State: Karnataka Area: 485 sq.km. Population:2,54,170 Normal Annual Rainfall: 636 mm 1.1 Aquifer management study area Aquifer mapping studies was carried out in HariharTaluk, Davanagere district of Karnataka, covering an area of 485 sq.kms under National Aquifer Mapping. Harihar Taluk of Davanagere district is located between north latitude 140 17’ 38” and 140 38’ 13” & east longitude 750 37’26” and 750 54’43”, and is covered in parts of Survey of India Toposheet Nos. 48N/11, 48N/14 & 48N/15. Taluk is bounded by HarapahalliTaluk in north, HonnalliTaluk in south, DavanagereTaluk in east and RanibennurTaluk of Haveri district on the western side. Location map of Harihar Taluk of Davanagere district is presented in Fig. 1. Fig. 1: Location Map of Harihar Taluk, Davanagere district 1 Harihar city is the Taluk headquarter of Harihar Taluk. -

District Profile

Davanagere District Disaster Management Plan CHAPTER –1 DISTRICT PROFILE - 1 - Davanagere District Disaster Management Plan 1. INTRODUCTION A great Maratha warrior by name Appaji Rao had rendered great service to Hyder Ali Khan in capturing Chitradurga fort. Hyder Ali Khan was very much pleased with Appaji Rao, who had made great sacrifices in the wars waged by him. Davanagere was handed over to Appaji Rao as a Jahagir. It was a very small village of about 500 houses in its perview. Appaji Rao had to toil for the upliftment of this area by inviting Maratha businessmen from neighbouring Maharastra. A large number of Marathas arrived at this place to carry on business in silk, brasserie and other materials. In due course, due to the incessant efforts of Appaji Rao, the Davanagere village grew into a city. Businessmen from neigbouring areas also migrated to try their fortunes in the growing city were successful beyond imagination in earning and shaping their future careers. These circumstances created an opportunity for the perennial growth of the town in modern days. The word ‘Davanager’ is derived from “Davanagere”, which means a rope in kannada language which was used for tying the horses by the villages. Around 1811 A.D., this area came to be called as ‘Davanagere’. Davanagere district occupies 12th place in Karnataka State with a population of 17,89,693 as per the general census of 2001. The following table demonstrates the block wise population of Davanagere district and the rate of literacy. The DDMP has been formed keeping in view of past experiences, suiting to the needs under the able leadership of Deputy Commissioner and in co-operation of all other departments and public at large. -

Bullapura Sand Block

FORM-I, PRE-FEASIBILTY & ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN of BULLAPURA SAND BLOCK (Block No:-30) Extent - 15.00 Acres At TUNGABHADRA RIVER BED Opposite to Sy No. – 32 to 40 Rampura Village, Honnali Taluka, Davangere District, Karnataka Of Bashua Ali 16 th Cross, 3 rd Main, J C Layout Harihar – 577601, Davanagerei Dist Karnataka State Government Land Method of Quarrying - Manual Period: 2017-18 to 2021-22 Prepared By GLOBAL Environment & Mining Services (Consulting Engineers, Mine Designers, Geologists & Surveyors) 3rd Main Road, Basaveswara Badavane HOSPET – 583201 , Bellary Dist. (Karnataka) Tel/Fax : +918394 651111/229433 e-mail : [email protected] Website : globalmining.in FORM 1 I. Basic Information: Sl. Item Details No. 1 Name of Project “Bullapura Sand Block” (Block No. 29 ) in Tungabhadra River Bed, opposite to Survey No. 3 - 40 Bullapura Village, Honnali Taluk, Davangere District, Karnataka. 2 Sl. No in the Sc hedule As per the MOEF notification J -13012/12/2013/ -IA -II ( I) dated 24th December 2013, the project is classified as Category “B2” under item 1(a). 3 Proposed Capacity/Length tonnage to be Proposed Capacity: 10691 Tonnes/ year. handled/command area/ Lease area/ Tonnage to be handled : 14734T (includes 10691T sand & number of wells to be drilled. 4043T waste) Lease area: 6.07 Ha.(15-00Acres) No wells need to be drilled 4 New/Expansion/Modernization New 5 Existing Capacity /Area etc Not Applicable 6 Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B2 7 Does it attract the specific condition? If No, yes, Pleased specify. 8 Does it attract the general condition? If Yes yes, Pleased specify. -

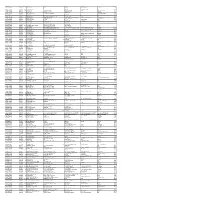

Police Station List

PS CODE POLOCE STATION NAME ADDRESS DIST CODEDIST NAME TK CODETALUKA NAME 1 YESHWANTHPUR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 2 JALAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 3 RMC YARD PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 4 PEENYA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 5 GANGAMMAGUDI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 6 SOLADEVANAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 7 MALLESWARAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 8 SRIRAMPURAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 9 RAJAJINAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 10 MAHALAXMILAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 11 SUBRAMANYANAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 12 RAJAGOPALNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 13 NANDINI LAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 14 J C NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 15 HEBBAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 16 R T NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 17 YELAHANKA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 18 VIDYARANYAPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 19 SANJAYNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 20 YELAHANKA NEWTOWN PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 21 CENTRAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 22 CHAMARAJPET PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 23 VICTORIA HOSPITAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 24 SHANKARPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 25 RPF MANDYA MANDYA 22 MANDYA 5 Mandya 26 HANUMANTHANAGAR PS BANGALORE -

Karnatak Central Government Funded Old Age Home

List of Institutions Receiving Grants from the Govt. of India for running Old Age Homes, Day Care Centre and Mobile Medicare Units for Senior Citizen 1. Sri Jagadguru Guledgudd-587203, Tq. Gurusiddeshwar Vidhya Bagalkot Badami, Distt. Bagalkot, OAH-1 Vardhak & Sanskritika (Phone 08357-50218) Samsthe 2. 335, 1st block, R.T. Nagar Nightingales Medical Main Road, Bangalore-560032 Bangalore DCC-1 Trust (Phone- 3548444, 3548666, Fax- 3548999) 3. 10/13, K.H.M Block, R.T.Nagar Educational Bangalore Ganganagar, Bangalore- OAH-1 Trust 560032 (Phone-080-7763100) 4. Near Evergreen School;, Sarvodaya Service Bangalore Vijayapura, Devanahalli Taluk, OAH-1 Society Bangalore Rural Distt. 5. No. 2362, MIG, III Stage, Mother's Care Education Yelahanka New Town, Bangalore OAH-1 Society Bangalore-560064 (Phone- 080-8460724, 8461623) 6. Mandur, Virgonagar (Via), Vidyaranya Education & Bangalore Bangalore East Taluk, OAH-1 Development Society Bangalore-560049. 7. No. 1, Khatra 117, Assessment No. 113/77, 12th Cross, Eshwar Education & Srigandha Nagar, Behind Veda Bangalore OAH-1 Welfare Society Garment Hegganahalli, Peenya 2nd Stage, Bangalore-560091 (Phone-080 8. Shridi Sai Baba Mandir Premises, Near Old Check Sri Shathashrunga Vidya Post, kamakshipalya II Stage, Bangalore OAH-1 Samasthe Magadi main Road, Bangalore- 560079. Phone- 080-3283823, 3488157, 8430331 9. Konanakunte Cross, Vasantpura Main Road, Ambigar Chowdaiah Vasantpura Village, H.No. 37, Bangalore OAH-2 Education Society Uttarahalli Hobli, Bangalore- 560061. (Phone-6666374, 6320043) 10. No. 12, 11th Main 2nd Stage, Mattadahally Binny Layout, Nagarabavi Bangalore Jagajivanram Sarvodaya OAH-1 Road, Vijayanagar, Bangalore- Sangha 40 (Phone 3495227, 3303772) 11. No. 26, Ashakatha Poshaka Bangalore Ashaktha Poshaka Sabha Sabha Road, OAH-1 Vishveswarpuram, Bangalore 12. -

Harihar Bar Association : Harihar Taluk : Harihar District : Davanagere

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : HARIHAR BAR ASSOCIATION : HARIHAR TALUK : HARIHAR DISTRICT : DAVANAGERE SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE VITTOBA RAO G K MYS/123/70 1 S/O G KESHAVA RAO HUDCO COLONY BEHIND POLICE STATION HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577601 VISWANATH HAM SAGAR MYS/13/71 2 S/O NEELAKANTASA CENTRAL STREET HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577601 HALAPPA B. KAR/367/76 S/O BASAPPA B 3 SHAMBHULINGAPPA NILAYA, VIDYA NAGAR CITY HARIHAR DAVANAGERE SHEJAPPA K B KAR/11/83 4 S/O BEERAPPA DOGGALLI , DODDABATHI HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577 601 1/33 3/17/2018 BHADRESHI B KAR/480/83 5 S/O kalappa B KUMBOBUR CHITRADURGA HARIHAR DAVANAGERE KALAL S M KAR/62/84 S/O MUKUNDAPPA KALAL 6 LAKSHMI NIVASA , BEHIND RAILWAY STATION, MAHALINGAPPA LAYOUT, HARIGARA TOWN, DEVANAGEREE HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577601 KITTUR SHAIKH IBRAHIM KAR/449/84 S/O HUSSAIN SAHEB 7 HOUSE NO 445 , 4TH MAIN, 2ND CROSS, HIGH SCHOOL EXTN. HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577601 PYARI ZAMROOD SHAIKH KAR/76/87 8 D/O H.SHAIKH HUNNUR NO. E/8, LABOURCOLONY, YANTRAPUR POST HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577601 GANGAPPA. B. KAR/383/88 9 S/O BALLUR HANUMANTHAPPA KUMBALUR POST HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577 530 2/33 3/17/2018 SYED KHALEELUR RAHAMAN KAR/250/90 10 S/O SYEDUMMER SAHEB F-76, HOSPITAL ROAD HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577 601 GURUNATHA RAO KULKARNI KAR/367/90 11 S/O V R KULKARNI NEAR ESHWARA TEMPLE ROA,D FORT A HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577 601 CHAINRAJ M.D. KAR/583/91 S/O SHA DALICHADHJI 12 140/3, 2ND MAIN, 2ND CROSS ,PJ EXTENSION CITY HARIHAR DAVANAGERE 577002 NISAR AHAMED KHAN KAR/678/91 S/O IBRAHIM KHAN H 13 BASAVESWARA BADAVANE NANDIGUDI ROAD, NEAR GANESH,, THEATRE MALEBENNUR CHITRADURGA . -

Water Quality of River Tungabhadra Due to the Discharge of Industrial Effluent at Harihar, District Davanagere, Karnataka State, India Basavaraj M

American Journal of Advanced Drug Delivery www.ajadd.co.uk Original Article Water Quality of River Tungabhadra due to the Discharge of Industrial Effluent at Harihar, District Davanagere, Karnataka State, India Basavaraj M. Kalshetty*1, Shobha.N2, M.B.Kalashetti3 and Ramesh Gani4 1B.L.D.E’S Science College Jamkhandi, Bagalkot District, Karnataka State, India 2Department of Chemistry, Bharathier University, Coimbatore 3Department of Chemistry, Karnataka University, Dharwad 4Department of Industrial Chemistry, Mangalore University Mangalore Date of Receipt- 09/02/2014 ABSTRACT Date of Revision- 14/02/2014 Date of Acceptance- 19/02/2014 Water is a prime mover of all activities and essential feature for all modern developments. Water is distributed in different forms, such as rain water, river water, spring water and mineral water. Rain water is considered to be the purest form, however, is associated with dissolved gases such as CO2, SO2, NH3 etc., from atmosphere. Water used for Industrial development and municipal purposes, it is better to ensure the quality of water for these purposes. There is influence of Industrial waste. Sewage on the water quality, the waste products can change the water Chemistry. Water gives life to Industries, but, Industries kill the water Chemistry. The waste water which emerges out after uses from industries have no definite composition, the pollutants associated with industrial effluents such as organic matter, Address for inorganic dissolved solids, fertilizer materials, suspended solids, Correspondence heavy metals from toxic pollutants and micro organisms and also pathogens. The industrial wastes are responsible for water color, B.L.D.E’S Science turbidity, odour, hardness, toxic elements, bacteria and micro College Jamkhandi, organisms. -

Booking Train Ticket Through Internet Website: Irctc.Co.In Booking

Booking Train Ticket through internet Website: irctc.co.in Booking Guidelines: 1. The input for the proof of identity is not required now at the time of booking. 2. One of the passengers in an e-ticket should carry proof of identification during the train journey. 3. Voter ID card/ Passport/PAN Card/Driving License/Photo Identity Card Issued by Central/State Government are the valid proof of identity cards to be shown in original during train journey. 4. The input for the proof of identity in case of cancellation/partial cancellation is also not required now. 5. The passenger should also carry the Electronic Reservation Slip (ERS) during the train journey failing which a penalty of Rs. 50/- will be charged by the TTE/Conductor Guard. 6. Time table of several trains are being updated from July 2008, Please check exact train starting time from boarding station before embarking on your journey. 7. For normal I-Ticket, booking is permitted at least two clear calendar days in advance of date of journey. 8. For e-Ticket, booking can be done upto chart Preparation approximately 4 to 6 hours before departure of train. For morning trains with departure time upto 12.00 hrs charts are prepared on the previous night. 9. Opening day booking (90th day in advance, excluding the date of journey) will be available only after 8 AM, along with the counters. Advance Reservation Through Internet (www.irctc.co.in) Booking of Internet Tickets Delivery of Internet Tickets z Customers should register in the above site to book tickets and for z Delivery of Internet tickets is presently limited to the cities as per all reservations / timetable related enquiries. -

L\1YSORE GAZETTEER MYSORE GAZETTEER

l\1YSORE GAZETTEER MYSORE GAZETTEER COMPILED FOR GOVERNMENT VOLUME II HISTORICAL PART l EDITED BY C. HAY AV ADANA RAO, B.A., B.L, Fellow, University of Mysore, Editor, Mysore Economic Journal, Bangalore. NEW EDITIO~ BANGALORE; PRINTED AT THE GOVERNMENT PRESS 1930 PREFACE HIS, Volume, forming Volume II of the ltfysore T Gazetteer, deals in a comprehensive manner with the History of Mysore. A two-fold plan has been adopted in the treatment of this subject. In view of the progress of archffiological research in the State during the past forty years, occasion has been taken to deal in an adequate fashion with the sources from which the materials for the recon struction of its ancient history are derived. The information scattered in the Journals of the learned Societies and Reports on Archreology has been carefully sifted and collected under appropriate heads. Among these are Epigraphy, Numismatics, Sculpture and Painting, Architecture, etc. The evidence available from these different sources has been brought together to show not merely their utility in elucidating the history of Mysore during its earliest times, for which written records are not available, but also to trace, as far as may be, with their aid, periods of history which would otherwi8e be wholly a blank. In dealing with that part of the history of Mysore for wbich written records are to any extent available, a more familiar plan has been adopted. It has been divided into periods and each period has been treated under convenient sub-heads. No person who writes on the history of Mysore can do so without being indebted to :Mr. -

Mgl- Di318-Unpaid Shareholders List As on 30

FOLIO-DEMAT ID DWNO NETDIV NAME ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 City PIN IN30223610002208 183013893 6.00 SRIVALSAN PILLAI 219 B POCKET-C SIDDHARTH EXTN NEW DELHI 110044 IN30011811279255 183014386 250.00 SUNITA BHATIA C-79 IIND FLOOR ASHOK VIHAR PHASE-I DELHI 110052 IN30051322499953 183017925 4168.00 RAVI KUKREJA 40 ALFREDA AVENUE MORLEY P CODE 6062 PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 111111 IN30048414768889 183018413 1.00 SANJAY GUPTA HOUSE NO 215 SECTOR 8 FARIDABAD HARYANA FARIDABAD 121004 IN30292710252507 183022658 500.00 DINESH CHAWLA HOUSE NO 1264 ARYAN ENCLAVE SECTOR 51 B CHANDIGARH 160047 IN30048417042869 183024408 1.00 LIBI JACOB OOMMEN V-14 GROUND FLOOR SECTOR 12 NOIDA UTTAR PRADESH 201301 1202060000069367 183011221 50.00 INDERA DEVI 7232 ROOP NAGAR NEW DELHI 110007 IN30160411531206 183011520 100.00 KISHAN CHAND H NO 340 BHAI PARMANAND COLONY MUKHERJEE NAGAR DELHI DELHI 110009 IN30051323019723 183012755 20.00 SUMAN HASIJA B 45 DAYANAND COLONY NEAR M C D SCHOOL LAJAPT NAGAR 4 NEW DELHI SOUTH DELHI NEW DELHI DELHI 110024 IN30371911001871 183012829 188.00 MADAN MOHAN C-140 BLOCK C DEFENCE COLONY NEW DELHI NEW DELHI NEW DELHI 110024 1201090002105893 183017360 8.00 POONAM SHARMA H. NO. 227 GALI NO. 4 DURGAPURI EXTN. DELHI 110093 IN30223610829087 183019526 10.00 UTTAM SINGH A A-10 KENDRIYA VIHAR SECTOR-56 GURGAON 122011 IN30154955949749 183010423 130.00 SAMIR GILANI UNIT 905 9TH FLOOR PLATINUM TOWER JLT CLUSTER 1 PO BOX 450132 DUBAI UAE 0 1203280000222453 183010486 25.00 BENOY CHERIAN . P O BOX 10315 DANWAY QATAR DOHA 0 1203280000472718 183010500 31.00 EMIL K PAUL . ALPHA LINK TECHNOLOGY W L L P O BOX 82584 DOHA 0 1203280000475343 183010501 250.00 MINNETTE AURELIA ANDRADE .