ICSID Case No. ARB/15/28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programme Guidelines Albania

Development of Monitoring Instruments for Judicial and Law Enforcement institutions in the Western Balkans 2009-2011 Programme Guidelines Albania With funding by the CARDS Regional Action Programme European Commission June 2010 Disclaimers This Report has not been formally edited. The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations and neither do they imply any endorsement. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Comments on this report are welcome and can be sent to: Statistics and Survey Section United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 5475 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 7 5475 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unodc.org Acknowledgements UNODC would like to thank the European Commission for the financial support provided for the preparation and publication of this report under the CARDS Regional Programme 2006. This report was produced under the responsibility of Statistics and Surveys Section (SASS) and Regional Programme Office for South Eastern Europe (RPOSEE) of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) based on research conducted during a research mission to Albania in September 2009 by UNODC and the Joint Research Centre on Transnational Crime (TRANSCRIME). -

TV and On-Demand Audiovisual Services in Albania Table of Contents

TV and on-demand audiovisual services in Albania Table of Contents Description of the audiovisual market.......................................................................................... 2 Licensing authorities / Registers...................................................................................................2 Population and household equipment.......................................................................................... 2 TV channels available in the country........................................................................................... 3 TV channels established in the country..................................................................................... 10 On-demand audiovisual services available in the country......................................................... 14 On-demand audiovisual services established in the country..................................................... 15 Operators (all types of companies)............................................................................................ 15 Description of the audiovisual market The Albanian public service broadcaster, RTSH, operates a range of channels: TVSH (Shqiptar TV1) TVSH 2 (Shqiptar TV2) and TVSH Sat; and in addition a HD channel RTSH HD, and three thematic channels on music, sport and art. There are two major private operators, TV Klan and Top Channel (Top Media Group). The activity of private electronic media began without a legal framework in 1995, with the launch of the unlicensed channel Shijak TV. After -

R Isk B U Lletin

ISSUE 1 | SEPTEMBER–OCTOBER 2020 THE CIVIL SOCIETY OBSERVATORY TO COUNTER ORGANIZED CRIME IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE SUMMARY HIGHLIGHTS 1. No lockdown for the Kotor gangs 4. The Balkan Route and COVID-19: For more than five years, there has been a gang war More restrictions, more misery between two criminal groups from Kotor, on the During 2015, tens of thousands of refugees and coast of Montenegro. While most of Montenegro migrants moved through South Eastern Europe on was in lockdown during the COVID-19 crisis, the their journeys to the West of the continent. Today, killings continued. Despite the ongoing violence, the so-called Balkan Route is largely closed: borders the two leaders of the feuding Kavač and Škaljari have been securitized, and desperate migrants and clans, who were arrested with much ado in 2018, asylum-seekers are being pushed back. Some of are now both out on bail. The new government in the few winners in this crisis are migrant smugglers. Montenegro has pledged to fight against organized We examine how a growing number of migrants crime and corruption. Will it be able to stop the are entering the Western Balkans from Greece via cocaine war? Albania, and the methods that are used to smuggle them. This story also highlights the impact that this 2. Albanian cannabis moves indoors is having in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where, because Albania has gained the dubious reputation of being of tight border controls with Croatia and fears of ranked as Europe’s top cannabis producer. Some COVID-19, there is a growing humanitarian crisis. -

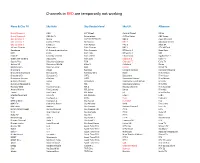

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

ALBANIA Ilda Londo

ALBANIA Ilda Londo porocilo.indb 51 20.5.2014 9:04:36 INTRODUCTION Policies on media development have ranged from over-regulation to complete liberali- sation. Media legislation has changed frequently, mainly in response to the developments and emergence of media actors on the ground, rather than as a result of a deliberate and carefully thought-out vision and strategy. Th e implementation of the legislation was ham- pered by political struggles, weak rule of law and interplays of various interests, but some- times the reason was the incompetence of the regulatory bodies themselves. Th e Albanian media market is small, but the media landscape is thriving, with high number of media outlets surviving. Th e media market suff ers from severe lack of trans- parency. It also seems that diversifi cation of sources of revenues is not satisfactory. Media are increasingly dependent on corporate advertising, on the funds arising from other busi- nesses of their owners, and to some extent, on state advertising. In this context, the price of survival is a loss of independence and direct or indirect infl uence on media content. Th e lack of transparency in media ratings, advertising practices, and business practices in gen- eral seems to facilitate even more the infl uences on media content exerted by other actors. In this context, the chances of achieving quality and public-oriented journalism are slim. Th e absence of a strong public broadcaster does not help either. Th is research report will seek to analyze the main aspects of the media system and the way they aff ect media integrity. -

Njoftimi-Media-Data-07.06.2017.Pdf

NJOFTIM PËR MEDIA Ditën e mërkurë, në datën 07 qershor 2017, u zhvillua mbledhja e radhës së Autoritetit të Page | 1 Mediave Audiovizive (AMA), ku morën pjesë anëtarët e mëposhtëm: Gentian SALA Kryetar Sami NEZAJ Zëvendëskryetar Agron GJEKMARKAJ Anëtar Gledis GJIPALI Anëtar Piro MISHA Anëtar Suela MUSTA Anëtar Zylyftar BREGU Anëtar AMA, pasi mori në shqyrtim çështjet e rendit të ditës, vendosi: 1. Miratimin e Numrit Logjik të Programit të shërbimeve programore kombëtare të përgjithshme dhe shërbimeve programore private rajonale/lokale, sipas listës bashkëlidhur. (Vendimi nr. 98, datë 07.06.2017); 2. Miratimin e rregullores “Për procedurat dhe kriteret e dhënies së autorizimeve”. (Vendimi nr. 99, datë 07.06.2017); 3. Miratimin e rregullores “Për procedurat dhe kriteret për dhënien e licencës lokale të transmetimit audioviziv në periudhën tranzitore”. (Vendimi nr. 100, datë 07.06.2017); 4. Miratimin e Rregullores “Për procedurat e inspektimit të veprimtarisë audiovizive të ofruesve të shërbimit mediatik audio dhe/ose audioviziv”. (Vendimi nr. 101, datë 07.06.2017); Po ashtu, AMA pasi shqyrtoi projekt-rregulloren “Mbi procedurat për shqyrtimin e ankesave nga Këshilli Ankesave dhe të drejtën e përgjigjes”, kërkoi rishikimin e tekstit të saj. Rruga “Papa Gjon Pali i II”, Tiranë |ëëë.ama.gov.al Tel. +355 4 2233370 |Email. [email protected] LISTA E NUMRIT LOGJIK TË SHËRBIMEVE PROGRAMORE AUDIOVIZIVE NLP SHËRBIMI PROGRAMOR Page | 2 1 "RTSH 1" 2 "RTSH 2" 3 "RTSH 3" 4 Top-Channel / Klan TV * 5 Klan TV / Top-Channel * 6 "Klan +" 7 "Vizion +" 8 “News -

Growing Like Weeds? Rethinking Albania's Culture of Cannabis

POLICY BRIEF GROWING LIKE WEEDS? Rethinking Albania’s culture of cannabis cultivation Fatjona Mejdini and Kristina Amerhauser DECEMBER 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This publication was produced with the financial support of the United Kingdom’s Conflict, Stability and Security Fund. Its contents are the sole responsibility of The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Kingdom. Special thanks to the valuable contributions of the numerous Albanian journalists who helped compile this report, in particular Driçim Çaka and Artan Hoxha. Policy briefs on current issues in the Western Balkans will be published on a reg- ular basis by the Civil Society Observatory to Counter Organized Crime in South Eastern Europe. The briefs draw on the expertise of a local civil-society network who provide new data and contextualize trends related to organized criminal activities and state responses to them. The Observatory is a platform that connects and empowers civil-society actors in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia. The Observatory aims to enable civil society to identify, analyze and map criminal trends, and their impact on illicit flows, governance, development, inter-ethnic relations, security and the rule of law, and supports them in their monitoring of national dynamics and wider regional and international organized- crime trends. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Fatjona Mejdini joined the GI-TOC as a field coordinator for the Balkans in September 2018. After a career as a journalist for national media in Albania, she was awarded the Hubert H Humphrey scholarship. In 2015, she joined Balkan Insight as a correspondent, reporting from the Balkan countries. -

Achievements Forum-2020 TOP100 Register

Achievements Forum-2020 TOP100 Register www.ebaoxford.co.uk 2020 The crisis transformations in the global economy and the pandemic posed a number of challenges for regional business - from the need for creative solutions in the field of personal safety and HR to the maximum strengthening of brand loyalty and brand recognition, expansion of partnerships and business geography. Today reality not only emphasises the importance of successful regional business for the development of the national economy, but also encourages international cooperation and introduction of innovative technologies and projects. Europe business Assembly continues annual research with the aim to select and encourage promising companies at the forefront of regional business. Following long-term EBA traditions, we are very pleased to present sustainable and promising companies and institutions to the global business community, and express our gratitude to them by presenting special awards. EBA created a special modern online platform to promote our members and award winners, exchange best practices, present achievements, share innovative projects and search for partners and clients. We conducted 3 online events on this platform in 2020. On the pages of this catalogue EBA proudly presents outstanding companies and personalities. They have all demonstrated remarkable resilience in a year of unprecedented challenges. We congratulate awardees and wish them further prosperity, health, happiness, love, family affluence and new business achievements! EBA team BUSINESS CARDS DR.DUDIKOVA CLINIC Ekaterina Dudikova Kiev, Ukraine phone: +38(067)172-53-47 e-mail: [email protected] www.dr-dudikova.clinic Dr.Dudikova Clinic was founded by Ekaterina Dudikova, a dermatologist-surgeon, a master of medicine with 14 years of experience. -

Legal Assessment ALB-Nhedits

2018 Legal Assessment MEDIA OWNERSHIP MONITOR ALBANIA DORIAN MATLIJA Part I: Description of the legislation on media concentration and ownership as well as its implementation, monitoring and transparency I.1. Legal framework Ø Which laws are supposed to prevent media concentration and monopolies? On what hierarchy level of law (e.g. constitution, civil code, special laws or decrees; national/regional) is media concentration being addressed? Neither the Albanian Constitution nor the Albanian Civil Code contain any provisions regarding media ownership concentration. The main piece of legislation laying down preventive rules on media concentration and monopolization is Law No. 97/2013, "On audio- visual media", as currently in force. This law contains provisions aimed at limiting the shares of a shareholder or his/her family members (up to the second degree) in a second or third media company, while it also introduces restrictions on the volume of advertising that a media company can broadcast. Another piece of legislation laying down rules for regulating monopolies is the Law 9121/2003 "On the protection of competition". This law sets out general rules for all types of businesses and addresses vertical control as well as indirect control issues. Ø What types of media are included in or excluded from the regulation? Is there regulation for digital media? According to the Law 97/2013 “On audio-visual media”, only those audio-visual media broadcasting on either analogue or digital frequencies fall within its scope. There is no equivalent law / regulation for print media, online, audio and cable media, or satellite broadcasting. Ø If no – or not sufficient – legislation exists: is there legislation in the making? What is the status quo of the political process? There is currently no political or legislative initiative pending or under consideration for introducing further regulation on media ownership, prevention of monopolisation and concentration of media ownership. -

£YUGOSLAVIA @Police Violence in Kosovo Province - the Victims

£YUGOSLAVIA @Police violence in Kosovo province - the victims Amnesty International's concerns Over the past year human rights abuses perpetrated by police against ethnic Albanians in the predominantly Albanian-populated province of Kosovo province in the Republic of Serbia have dangerously escalated. Thousands of ethnic Albanians have witnessed police violence or experienced it at first hand. In late July and early August, within a period of two weeks, three ethnic Albanians were shot dead by police officers and another wounded. Two other ethnic Albanians were shot dead near the border with Albania by officers of the Yugoslav Army. In several of these cases the authorities claimed that police or military had resorted to firearms in self-defence. However, in at least two cases, one of them involving the death of a six-year-old boy, the police officers in question do not appear to have been under attack. Amnesty International fears that ethnic tensions which are potentially explosive have risen as officers of the largely Serbian police force have increasingly resorted to the routine use of violence. These developments have taken place in the context of a continued confrontation between the Serbian authorities and ethnic Albanians, the majority of whom refuse to recognize Serbian authority in the province and support the demand of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), Kosovo's main party representing ethnic Albanians, for the secession, by peaceful means, of the province from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). Amnesty International has no position on the status of Kosovo province; the organization is concerned solely with the protection of the human rights of individuals. -

Albania: Blood Feuds

Country Policy and Information Note Albania: Blood feuds Version 4.0 February 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

Police Integrity and Corruption in Albania 8.2

INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY AND MEDIATION Police Integrity and Corruption in Albania Institute for Democracy and Mediation 3 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 8 2. Introduction 13 3. Methodology 14 3.1. Methodology of Survey with Citizens 15 3.2. Methodology of Survey with State Police Officials 15 3.3. Qualitative Analysis 16 3.4. Interviews with Hypothetical Scenarios 16 4. Police Corruption 18 4.1. What Is Corruption? 18 4.2. Police Corruption and Its Types 20 4.3. Corruption, Deviance and Misconduct 25 4.4. Police Integrity and Corruption 30 5. Police Corruption in Albania 31 5.1. Corruption as a General Phenomenon 31 5.2. Types of Corruption 36 5.3. Police Corruption in Albania 39 6. Literature Review on Factors of Police Corruption 41 6.1. Combination of PESTL Factors 42 6.2. Combination of Structural and Cultural Influences 43 6.3. Combination of Constant and Variable Factors 44 6.4. The Combination of Individual, Organizational and Societal Factors 48 6.5. Other Factors 53 7. Assessment of State Police Anticorruption Framework in Albania 54 7.1. Anticorruption Policy 55 7.1.1. National Anti-Corruption Strategy 2008-2013 55 7.1.2. State Police Strategy 2007-2013 58 7.1.3. National Plan on Implementation of Stabilization and Association Agreement 2009-2014 59 7.2. Legal Framework 62 7.3. Institutional Framework 67 7.4. Results in the Fight against Corruption 70 8. Extent and types of police corruption in Albania 77 8.1. Extent of Spread of Corruption 77 8.1.1. Spread of Corruption According to the Public 78 8.1.2.