Research Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Special Trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300

Place Name Code Hub Surch Regional A KRIEK (special trip) XXXX WER Yes AANDRUS, Bloemfontein 9300 BFN No AANHOU WEN, Stellenbosch 7600 SSS No ABBOTSDALE 7600 SSS No ABBOTSFORD, East London 5241 ELS No ABBOTSFORD, Johannesburg 2192 JNB No ABBOTSPOORT 0608 PTR Yes ABERDEEN (48 hrs) 6270 PLR Yes ABORETUM 3900 RCB Town Ships No ACACIA PARK 7405 CPT No ACACIAVILLE 3370 LDY Town Ships No ACKERVILLE, Witbank 1035 WIR Town Ships Yes ACORNHOEK 1 3 5 1360 NLR Town Ships Yes ACTIVIA PARK, Elandsfontein 1406 JNB No ACTONVILLE & Ext 2 - Benoni 1501 JNB No ADAMAYVIEW, Klerksdorp 2571 RAN No ADAMS MISSION 4100 DUR No ADCOCK VALE Ext/Uit, Port Elizabeth 6045 PLZ No ADCOCK VALE, Port Elizabeth 6001 PLZ No ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 DUR No ADDNEY 0712 PTR Yes ADDO 2 5 6105 PLR Yes ADELAIDE ( Daily 48 Hrs ) 5760 PLR Yes ADENDORP 6282 PLR Yes AERORAND, Middelburg (Tvl) 1050 WIR Yes AEROTON, Johannesburg 2013 JNB No AFGHANI 2 4 XXXX BTL Town Ships Yes AFGUNS ( Special Trip ) 0534 NYL Town Ships Yes AFRIKASKOP 3 9860 HAR Yes AGAVIA, Krugersdorp 1739 JNB No AGGENEYS (Special trip) 8893 UPI Town Ships Yes AGINCOURT, Nelspruit (Special Trip) 1368 NLR Yes AGISANANG 3 2760 VRR Town Ships Yes AGULHAS (2 4) 7287 OVB Town Ships Yes AHRENS 3507 DBR No AIRDLIN, Sunninghill 2157 JNB No AIRFIELD, Benoni 1501 JNB No AIRFORCE BASE MAKHADO (special trip) 0955 PTR Yes AIRLIE, Constantia Cape Town 7945 CPT No AIRPORT INDUSTRIA, Cape Town 7525 CPT No AKASIA, Potgietersrus 0600 PTR Yes AKASIA, Pretoria 0182 JNB No AKASIAPARK Boxes 7415 CPT No AKASIAPARK, Goodwood 7460 CPT No AKASIAPARKKAMP, -

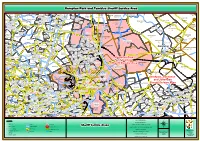

Gauteng Gauteng Kempton Park and Tembisa Sheriff Service Area

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !.ñ!C# # # # !C # $ # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ñ # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C# # # # # $ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # !C# # # #!C# # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ñ # # !C # #!C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ### # !C !C # # # # # # !C # # ## ## !C !C # # # !. # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # #ñ# # # !C # # # # ^ # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # !C # # !C# # ## ## # # # # !C # # # # !C# # # # # # !C # $ # # !C # # # # ^ # # # !C # ^ # # !C # ## # # !C #!C # # # # # # # # # # # ñ ## # # # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # -

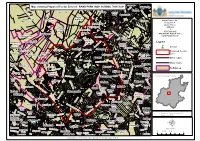

Map Showing Proposed Feeder Zone Of

n Nooitgedacht Bloubosrand e Fourways Kya Sand SP p D p o MapA sHhowing Proposed Feeder Zone of : RAND PARK HIGo H SCJHohOanOneLsb 7ur0g0151241 lie Magaliessig tk u s B i North g e Hoogland l L W e W a y s Norscot i e ll r Cosmo City ia s Noordhang Jukskei m N a n i N a r Park u Douglasdale i d a c é o M North l Rietfontein AH Sonnedal AH Riding AH Bryanston District Name: JN Circuit No: 4 North Riding G ro Cluster No: 2 sv Bellairs Park en Jackal or Address: Creek Golf Northworld AH d 1 J n a a Estate Olivedale c l ASSGAAI AVE a r n r o Northgate a e t n b s RANDPARK RIDGE EXT1 Zandspruit SP da n m a u y Rietfontein AH r RANDPARK RIDGE Sharonlea C s B n y Vandia i a H a o Sundowner Hunters K Grove m M e e Zonnehoewe AH Hill A. h s Roodekrans Ext c t Legend u e H. SP o Beverley a AH F d Country s. e Gardens er r Life Ruimsig Noord et P School P Bryanbrink Park Sundowner Northworld Sonneglans Tres Jolie AH Laser Park t Kensington B Proposed Feeder r ord E Alsef AH a xf t Ruimsig w O o Zone Ruimsig AH .S Strijdompark n Lyme Park .R Ambot AH C Bond Bromhof H New Brighton a Other roads n s Boskruin Eagle Canyon s Schoeman S Han t Hill Ferndale Kimbult AH r ij Major roads Poortview t d Hurlingham e ut o Willowbrook ho m AH W r d Bordeaux e Harveston AH st Malanshof r e Y e r d o Willowild Subplaces uge R Kr Randpark ep w ul n ub Pa lic r a s e a Ridge Ruiterhof h i R V c t a Amorosa Aanwins AH i ic b N r Honeydew s ie k i i Glenadrienne SP1 e r r d e Ridge h President d i Jo Moret n Craighall Locality in Gauteng Province C hn Vors Fontainebleau D ter Ridge e H J Wilro Wilgeheuwel a J n Radiokop . -

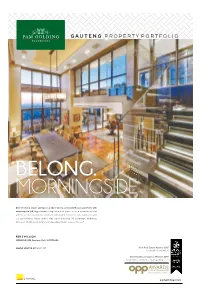

Gauteng Property Portfolio

GAUTENG PROPERTY PORTFOLIO BELONG. MORNINGSIDE One-of-a-kind, secure and spacious triple-storey, corner penthouse apartment, with uninterrupted 270-degree views. Refrigerated walk-in wine room, 4 palatial bedrooms with the wooden floor theme continued, with marble covered en suite bathrooms and a state-of-the-art home cinema with top-of-the-range AV equipment. Numerous balconies, all with views, with a heated pool and steam-room on the roof. R39.5 MILLION MORNINGSIDE, Gauteng Ref# HP1139604 WAYNE VENTER 073 254 1453 Best Real Estate Agency 2015 South Africa and Africa Best Real Estate Agency Website 2015 South Africa and Africa / pamgolding.co.za pamgolding.co.za EXERCISE YOUR FREEDOM 40KM HORSE RIDING TRAILS Our ultra-progressive Equestrian Centre, together with over 40 kilometres of bridle paths, is a dream world. Whether mastering an intricate dressage movement, fine-tuning your jump approach, or enjoying an exhilarating outride canter, it is all about moments in the saddle. The accomplished South African show jumper, Johan Lotter, will be heading up this specialised unit. A standout health feature of our Equestrian Centre is an automated horse exerciser. Other premium facilities include a lunging ring, jumping shed, warm-up arena and a main arena for show jumping and dressage events. The total infrastructure includes 36 stables, feed and wash areas, tack- rooms, office, medical rooms and groom accommodation. Kids & Teens Wonderland · Sport & Recreation · Legendary Golf · Equestrian · Restaurants & Retail · Leisure · Innovative Infrastructure -

Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 56 Albertsville R1,150,000

Neighbourhood On Show 11 February 2018 Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 56 Albertsville R1,150,000 Jawitz Properties 56 Albertsville R1,295,000 Jawitz Properties 36 Atholl R8,990,000 Seeff Properties 36 Atholl R8,200,000 Seeff Properties 47 Atholl R7,950,000 Jawitz Properties 47 Atholl R7,495,000 Jawitz Properties 68 Atholl R12,950,000 Vered Estates 68 Atholl R9,500,000 Vered Estates 103 Atholl R13,900,000 Pam Golding Properties 103 Atholl R10,900,000 Pam Golding Properties 103 Atholl R8,900,000 Pam Golding Properties 55 Barbeque Downs R2,980,000 Jawitz Properties 55 Barbeque Downs R2,090,000 Jawitz Properties 40 Bareque Downs R1,995,000 Seeff Properties 125 Bedford Gardens R1,059,000 Firzt Realty Company 23 Bedford Park R6,500,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 123 Bedford Park R2,100,000 Firzt Realty Company 23 Bedfordview R5,500,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 23 Bedfordview R5,599,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 23 Bedfordview R3,850,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 23 Bedfordview R3,699,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 51 Bedfordview R9,999,000 Jawitz Properties 21 Benmore R3,499,000 Lew Geffen / Sotheby's International Realty 40 Benmore R2,750,000 Seeff Properties 83 Berario R2,450,000 Fine & Country International 16 Beverley R2,350,000 Huizemark Holdings 88 Beverley R2,500,000 Tyson Properties 88 Beverley R1,335,000 Tyson Properties 93 Beverley R2,725,000 Chas Everitt International Property Group 118 Beverley R4,450,000 Pam Golding Properties 118 -

![SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9301/sida-gauteng-2011-2-pdf-599301.webp)

SIDA Gauteng 2011[2].Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Letter from Ria Schoeman PhD 4 Abbreviations and Acronyms 4 Helpline and Hotlines in South Africa MUNICIPALITIES 5 City of Johannesburg 29 City of Tshwane 45 Ekurhuleni 61 Metsweding 64 Sedibeng 72 West Rand 1 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARV: Antiretroviral OVC: Orphans and Vulnerable Children PMTCT Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission STI: Sexually transmitted infection HELPLINE AND HOTLINES IN SOUTH AFRICA Abortion Helpline 080 117 785 Aid for AIDS Helpline 0860 100 646 Alcoholics Anonymous 0861 HELPAA (0861 435 722) Ambulance (Private) 082 911 Ambulance (Public) 10177 Cell phone Emergency Number 112 Child Victims of Sexual, Emotional 0800 035 553 and Physical Abuse Helpline Childline 0800 055 555 Crime Stop 0860 010 111 Department of Education Helpline 0800 202 933 Department of Health Helpline 0800 005 133 Department of Home Affairs Hotline 0800 601 190 Department of Social Development 0800 121 314 Substance Abuse Helpline Emergency Contraception Hotline 0800 246 432 Gay and Lesbian Network Helpline 0860 333 331 HIV Medicines Helpline 0800 212 506 HIV-911 Referral Centre 0860 HIV 911 (0860 448 911) Human Rights Advice Line 0860 120 120 Lifeline Southern Africa 0861 322 322 Legal Aid South Africa Advice Line 0800 204 473 loveLife Sexual Health Line 0800 121 900 (thetha junction) Marie Stopes Clinic Toll Free Number 0800 117 785 mothers2mothers 0800 668 4377 MRI Criticare Emergency Service 0800 111 990 National AIDS Helpline 0800 012 322 National HIV Health Care Workers Hotline 0800 212 506 National Youth Information -

(Legal Gazette A) Vol 669 No 44290

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant March Vol. 669 19 2021 No. 44290 Maart PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5845 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 44290 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 44290 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 19 MARCH 2021 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 14 ORDERS OF THE COURT • BEVELE VAN DIE HOF National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 16 GENERAL • ALGEMEEN National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 29 ADMINISTRATION OF ESTATES ACTS NOTICES / BOEDELKENNISGEWINGS Form/Vorm J295 ................................................................................................................................................... -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 102 4Tune on Aston R5

Neighbourhood On Show 05 August 2018 Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 102 4tune on Aston R5,999,000 Dogon Group Properties 20 Abbotsford R4,550,000 Lew Geffen Sotheby's International Realty 44 Atholl R3,450,000 Tyson Properties 58 Atholl R10,850,000 Vered Estates 64 Atholl R1,549,000 Vered Estates 66 Atholl R5,900,000 Jawitz Properties 66 Atholl R8,500,000 Jawitz Properties 68 Atholl Gardens R2,490,000 Jawitz Properties 78 Auckland Park R1,750,000 RE/MAX International Property Group 26 Bedford Park R2,499,000 Lew Geffen Sotheby's International Realty 26 Bedfordview R6,999,000 Lew Geffen Sotheby's International Realty 69 Bedfordview R3,850,000 Jawitz Properties 56 Benmore Gardens R5,800,000 Hamilton's Property Portfolio 77 Benmore Gardens R2,010,000 RE/MAX International Property Group 89 Benmore Gardens R2,875,000 Pam Golding Properties 100 Berario R1,890,000 Gaylin Estates 108 Bergbron R3,100,000 Huizemark Holdings 27 Beverley R3,850,000 Lew Geffen Sotheby's International Realty 27 Beverley R3,395,000 Lew Geffen Sotheby's International Realty 50 Beverley R1,250,000 Tyson Properties 73 Beverley R2,699,000 Jawitz Properties 95 Beverley R2,750,000 Pam Golding Properties 108 Beverley R2,775,000 Huizemark Holdings 65 Blairgowrie R1,749,000 Vered Estates 65 Boskruin R3,150,000 Vered Estates 104 Bramley R660,000 Dogon Group Properties 16 Bramley Park R2,399,000 Adrienne Hersch Properties 49 Broadacres R5,495,000 Tyson Properties 74 Broadacres R1,149,000 Jawitz Properties 38 Bromhof R1,399,000 Chas Everitt International Property Group -

Region B Contact & Information Directory

REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY UPDATED JANUARY 2016 REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY: JANUARY 2016 INDEX NAME PAGE Emergency Numbers …………………………………………………………………… 1 Head Office Staff A – Z …………………………………………………………………… 1 – 6 Ward Councillors …………………………………………………………….…….. 6 -7 Ward Governance Administrators …………………………………………………………………… 8 PR Councillors …………………………………………………………………… 8 Group Citizen Relationship & Urban Management (CRUM): Head Office …………………………… 8 - 9 Regional Directors A – G …………………………………………………………... 9 - 10 Citizen Relationship & Urban Management Management Support …………………………………………………… 10 Area Based Management …………………………………………………… 11 Citizen Relationship Management …………………………………………………... 11 Integrated Service Delivery …………………………………………………... 12 Planning, Profiling & Data Management …..……………………………………… 12 Health Community Health Clinics …………………………………………………… 13 – 14 Environmental Health …………………………………………………… 15 – 18 Housing …………………………………………………………………… 19 Libraries …………………………………………………………………… 20-21 Social Development TDC (Transformation & Development Centre) ………………………………………… 22 Techno Centre …………………………………………………………………… 23 Sport and Recreation Recreation …………………………………………………………………… 23 Recreation Centres …………………………………………………………………… 24 NAME PAGE Sport …………………………………………………………………… 25 Sports Clubs & Stadiums …………………………………………………………………… 25 – 26 Aquatics …………………………………………………………………… 26 Swimming Pools …………………………………………………………………… 26 – 27 Group Finance Revenue Shared Services Centre ………………………………………………….. 27 Development Planning Building Control -

Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 71 Abbotsford R6 400 000

Neighbourhood On Show 28 February 2016 Page Suburb Price of Property Agency Name 71 Abbotsford R6 400 000 Pam Golding 196 Albertskroon R1 320 000 Sotheby's 218 Albertville R1 250 000 Fine & Country 144 Albertville R880 000 Jawitz Properties 106 Aldara Park R2 950 000 Seeff 127 Allens Nek R1 599 000 RE/MAX 140 Atholhurst R3 800 000 Jawitz Properties 26 Atholl R9 950 000 Ennik Estates 48 Atholl R4 000 000 Firzt Realty 48 Atholl R5 200 000 Firzt Realty 140 Atholl R6 900 000 Jawitz Properties 67 Atholl R15 900 000 Pam Golding 76 Atholl R3 500 000 Pam Golding 28 Atholl R4 500 000 Russell Fisher 96 Atholl R4 700 000 Seeff 177 Atholl R8 900 000 Sotheby's 35 Atholl R12 000 000 Vered Estates 35 Atholl R5 250 000 Vered Estates 44 Atholl R2 499 000 Vered Estates 87 Auckland Park 495 000 Pam Golding 27 Barbeque Downs R2 399 000 Ennik Estates 151 Barbeque Downs R1 950 000 Jawitz Properties 224 Beaulieu R5 400 000 Country Life Properties 162 Bedford Gardens R1 299 000 Hall Real Estate 185 Bedford Park R3 300 000 Sotheby's 40 Bedford Park R6 000 000 Vered Estates 162 Bedfordview R4 699 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R5 500 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R3 700 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R3 900 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R3 900 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R3 450 000 Hall Real Estate 162 Bedfordview R1 950 000 Hall Real Estate 152 Bedfordview R9 999 000 Jawitz Properties 88 Bedfordview 27 000 000 Pam Golding 184 Bedfordview R4 000 000 Sotheby's 184 Bedfordview R6 900 000 Sotheby's 184 Bedfordview R3 900 000 Sotheby's -

National Liquor Authority Register

National Liquor Register Q1 2021 2022 Registration/Refer Registered Person Trading Name Activities Registered Person's Principal Place Of Business Province Date of Registration Transfer & (or) Date of ence Number Permitted Relocations or Cancellation alterations Ref 10 Aphamo (PTY) LTD Aphamo liquor distributor D 00 Mabopane X ,Pretoria GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 12 Michael Material Mabasa Material Investments [Pty] Limited D 729 Matumi Street, Montana Tuine Ext 9, Gauteng GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 14 Megaphase Trading 256 Megaphase Trading 256 D Erf 142 Parkmore, Johannesburg, GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 22 Emosoul (Pty) Ltd Emosoul D Erf 842, 845 Johnnic Boulevard, Halfway House GP 2016-10-07 N/A N/A Ref 24 Fanas Group Msavu Liquor Distribution D 12, Mthuli, Mthuli, Durban KZN 2018-03-01 N/A 2020-10-04 Ref 29 Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd Golden Pond Trading 476 (Pty) Ltd D Erf 19, Vintonia, Nelspruit MP 2017-01-23 N/A N/A Ref 33 Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd Matisa Trading (Pty) Ltd D 117 Foresthill, Burgersfort LMP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 34 Media Active cc Media Active cc D Erf 422, 195 Flamming Rock, Northriding GP 2016-09-05 N/A N/A Ref 52 Ocean Traders International Africa Ocean Traders D Erf 3, 10608, Durban KZN 2016-10-28 N/A N/A Ref 69 Patrick Tshabalala D Bos Joint (PTY) LTD D Erf 7909, 10 Comorant Road, Ivory Park GP 2016-07-04 N/A N/A Ref 75 Thela Management PTY LTD Thela Management PTY LTD D 538, Glen Austin, Midrand, Johannesburg GP 2016-04-06 N/A 2020-09-04 Ref 78 Kp2m Enterprise (Pty) Ltd Kp2m Enterprise D Erf 3, Cordell