Chapter 3: Land Use, Zoning, and Public Policy A. INTRODUCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ninth Amendment to Offering Plan Relating to Premises 32 Gramercy Park South New York I New York

NINTH AMENDMENT TO OFFERING PLAN RELATING TO PREMISES 32 GRAMERCY PARK SOUTH NEW YORK I NEW YORK The Offering Plan dated June 27, 1983 to convert to cooperative ownership premises at 32 Gramercy Park South, New York, New York is hereby amended by this Ninth Amendment as follows: I. Annexed hereto and marked as Exhibit A is a list of the unsold shares held by Anby Associates and the apartments to which these shares are allocated. II. The aggregate monthly maintenanc~ for the Spon~~r'~ units is $58,560.98. III. The aggregate monthly rent collected for the Sponsor's units is $35,017.32. IV. The Sponsor's financial obligation at this time is maintenance and the balance of approximately $30,000 for a window assessment. Sponsor and the cooperative's Board are in dispute of the maintenance records for the years 1987 through 1989. Sponsor gave up control of the Board in 1987 and has requested the back maintenance records to track the discrepancy. The balance of the window assessment will be paid as soon as the corporation's records are reviewed and the discrepancy is settled. The Sponsor is not aware of any other obligation. V. The Sponsor's units are pledged as collateral for a loan with Israel Discount Bank of New York. The present balance of the loan is $1,323,140. The monthly payments are of interest only at. the rate of 12% and the loan matures September 3, 1991. The balance is reduced with each sale so that the monthly payment is not a constant amount. -

Duke Ellington Monument Unveiled in Central Park Tatum, Elinor

Document 1 of 1 Duke Ellington monument unveiled in Central Park Tatum, Elinor. New York Amsterdam News [New York, N.Y] 05 July 1997: 14:3. Abstract A monument to jazz legend Duke Ellington was unveiled at Duke Ellington Circle on the northeast corner of Central Park on Jul 1, 1997. The jet black, 25-ft-high memorial was sculpted by Robert Graham and depicts Ellington, standing by his piano. The statue is a gift from the Duke Ellington Memorial Fund, founded by Bobby Short. Full Text Duke Ellington monument unveiled in Central Park The four corners of Central Park are places of honor. On the southwest gateway to the park are monuments and a statue of Christopher Columbus. On the southeast corner is a statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman. Now, on the northeast corner of the park, one of the greatest jazz legends of all time and a Harlem hero, the great Duke Ellington, stands firmly with his piano and his nine muses to guard the entrance to the park and to Harlem from now until eternity. The monument to Duke Ellington was over 18 years in the making, and finally, the dream of Bobby Short, the founder of the Duke Ellington Memorial Fund, came to its fruition with the unveiling ceremony at Duke Ellington Circle on 110th Street and Fifth Avenue on Tuesday. Hundreds of fans, family, friends and dignitaries came out to celebrate the life of Duke Ellington as he took his place of honor at the corner of Central Park. The jet black, 25-foot-high memorial sculpted by Robert Graham stands high in the sky, with Ellington standing by his piano, supported by three pillars of three muses each. -

Nyc Alliance to Preserve Public Housing

NYC ALLIANCE TO PRESERVE PUBLIC HOUSING July 23rd, 2013 Chairman John B. Rhea New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) 250 Broadway New York, NY 10007 Dear Chairman Rhea, Participants in the NYC Alliance to Preserve Public Housing respectfully submit the attached comments as our collective response to the proposed NYCHA Draft FY2014 Annual Plan. The Alliance is a collaboration of resident leaders/organizations, housing advocates, and concerned elected officials to press for policies to strengthen our public housing communities and extend housing opportunities under the Section 8 voucher program. We seek a stronger resident and community voice in government decisions that affect these communities, as well as greater openness and accountability on the part of the New York City Housing Authority. Alliance members have reviewed the NYCHA Draft FY2014 Annual Plan. This position paper describes key issues we have identified in the plan and puts forward our joint recommendations. Our concerns are organized under the following issue headings: NYCHA Must Retain All Its Operating Revenues Halt the Current NYCHA Infill Land-Lease Plan Moving-to-Work (MTW): Binding Agreement Needed Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Cuts Keep NYCHA Centers Open; Retain NYCHA Jobs Where is the NYCHA Disaster Preparation Plan? Is a One-Evening, Three-Hour Public Hearing Enough? This is a crucial time for renewal and preservation of our affordable, low-income housing resources and a return to NYCHA communities that have sustained hope for generations. We offer our perspectives and ideas as partners in a shared vision of a renewed, persevering, and accountable New York City Housing Authority. -

7517 Fifth Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11209 Mixed Use Building Bay Ridge

Mixed Use – Bay Ridge 7517 Fifth Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11209 Mixed Use Building Bay Ridge Property Information Address: 7517 5th Avenue For more information, Brooklyn, NY 11209 please contact Exclusive Neighborhood: Bay Ridge Marketing Team Cross Streets: Bay Ridge Pkwy & 76th Street Block: 5942 Lot: 4 Lot Dimensions: 21.42 ft x 109.67 ft irreg. Peter Matheos Zoning: C1-3/R6B/BR Vice President [email protected] Lot SF: 2,349 FAR: 2.00 Adan Elias Kornfeld Building Information Associate [email protected] Building Size: 21 ft x 55 ft Irreg. Building Class: S2 Tax Class 1 (718) 568-9261 Stories: 3 Residential Units: 2 Commercial Units 1 Total Units 3 Residential SF: 2,586 Commercial SF: 1,294 Gross SF: 3,880 approx. Assessment (16/17): $50,494 Taxes (16/17): $9,874 TerraCRG has been retained to exclusively represent ownership in the sale of 7517 Fifth Avenue in the Bay Ridge neighborhood of Brooklyn. Located on Fifth Avenue between Bay Ridge Pkwy and 76th Street, the three-story, ~3,880 SF building consists of two floor-through 3-bedroom apartments and one retail unit. Subway currently occupies the retail space which has seven years remaining with two five-year option. Subway is responsible for 75% of the water bill as well as the tax increase over the base year, 2013. The average rent for the residential units are $1,400 and $1,600/Mo, while the market rent for renovated units of this size is $2,500/Mo. The property has a gross annual revenue for the package is ~$81,732. -

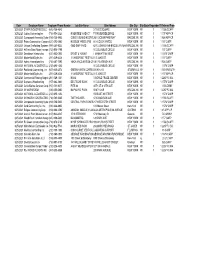

Date Employer Name Employer Phone Numbe Job Site Name Site Address Site City Site State Requmber Filreferred from 3/25/2021 STAR

Date Employer Name Employer Phone Numbe Job Site Name Site Address Site City Site State Requmber FilReferred From 3/25/2021 STARR INDUSTRIES LLC (646) 756-4648 3 TIMES SQUARE NEW YORK NY 1 1 1556 SCAFF 3/25/2021 Judlau Contracting Inc (718) 554-2320 RIVERSIDE VIADUCT 715 RIVERSIDE DRIVE NEW YORK NY 1 1 157 APP-CP 3/25/2021 Component Assembly Syste (914) 738-5400 CONEY ISLAND HOSPIT 2601 OCEAN PARKWAY BROOKLYN NY 1 1 926 APP-CP 3/25/2021 Pabco Construction Corpora (631) 293-6860 HUDSON YARDS (PM) 50 HUDSON YARDS NEW YORK NY 1 1 157 CARP 3/25/2021 Unique Scaffolding Systems (908) 241-9322 GMD SHIP YARD 63 FLUSHING AVE-BROOKLYN NAVYBROOKLYN NY 1 1 1556 SCAFF 3/25/2021 Hi Tech Data Floors Incorpor(732) 905-1799 10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK NY 157 CARP 3/25/2021 Donaldson Interiors Inc. (631) 952-0800 ERNST & YOUNG 1 MANHATTAN WEST NEW YORK NY 1 1 157W CARP 3/25/2021 Modernfold/Styles Inc (201) 329-6226 1 VANDERBILT RESTAU 51 E 42ND ST NEW YORK NY 1 1 157 CARP 3/25/2021 Ashnu International Inc. (718) 267-7590 YMCA VACCINATION CE1401 FLATBUSH AVE BROOKLYN NY 1 1 926 CARP 3/25/2021 NATIONAL ACOUSTICS LLC(212) 695-1252 10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE NEW YORK NY 157W CARP 3/25/2021 Poolbrook Contracting, Inc (607) 435-3578 GREEN HAVEN CORREC594 NY-216 STORMVILLENY 1 1 740 MWDUTH 3/25/2021 Modernfold/Styles Inc (201) 329-6226 1 VANDERBILT RESTAU 51 E 42ND ST NEW YORK NY 1 1 157 APP-CP 3/25/2021 Commercial Flooring Mngmt (201) 729-1331 HANA 3 WORLD TRADE CENTER NEW YORK NY 1 1 2287 FC MA 3/25/2021 Supreme Woodworking (917) 882-4860 DEUTSCHE BANK 10 COLUMBUS -

Resource Manual12 14 00

RESOURCE MANUAL AFTER SCHOOL PROGRAMS I.S. 143 (Beacon Program – La Plaza / Alianza Dominicana, Inc.) 515 W. 182nd St. New York, NY 10033 (212) 928-4992 Contact: Sebastian I.S. 218 (Salome Urena School – Children’s Aid Society) 4600 Broadway New York, NY 10040 (212) 567-2322 or (212) 569-2880 Contact: Neomi Smith CHILDCARE Agency for Child Development (Citywide Application of Enrollment) 109 E. 16th St. New York, NY (212) 835-7715 or 7716 Fax (212) 835-1618 Asociaciones Dominicanos Daycare Center 510 W. 145th St. New York, NY 10031 (690) 329-3290 Early Intervention Services (800) 577-2229 Familia Unida Daycare 2340 Amsterdam Avenue, (between 176th & 177th St.) (212) 795-5872 Contact: Felix Arias Fort George Community Enrichment Center 1525 St. Nicholas Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10033 (Corner of 186th St.) (212) 927-2210 Contact: Awilda Fernandez · Child care · Head Start · WEP Rena Day Care Center 639 Edgecombe Avenue, New York, NY 10032 (Corner of 166th Street) 212-795-4444 Last Revised 8/7/03 1 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SERVICES D. O. V. E. Program (212) 305-9060 Fax (212) 305-6196 Alma Withim Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation 76 Wadsworth Ave. (between 176 & 177 St.) (212) 822-8300 Fax (212) 740-9646 Maria Lizardo Sarah Crawford Banda Ruby Barrueco Dulce Olivares Nuevo Amanecer – Centro del Desarrollo de la Mujer Dominicana 359 Ft. Washington Avenue, #1G New York, NY 10033 (212) 568-6616 Fax (212) 740-8352 Mireya Cruz Jocelin Minaya Vilma Ramirez Project Faith (212) 543-1038 Fax (212) 795-9645 Iris Burgos DRUG & ALCOHOL ABUSE SERVICES CREO: Center for Rehabilitation, Education and Orientation. -

United States District Court Southern District of New York

Case 1:21-cv-02221 Document 1 Filed 03/15/21 Page 1 of 64 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK HOUSING RIGHTS INITIATIVE Plaintiff, v. COMPASS, INC.; 65 BERGEN LLC; THE STRATFORD, LLC; CORCORAN GROUP LLC; PROSPECT OWNERS CORP.; BOLD LLC; RING DING LLC; E REALTY INTERNATIONAL CORP; JACKSON HT. ROOSEVELT DEVELOPMENT II, LLC; MORGAN ROSE REALTY, LLC; BTG LLC; M Q REALTY LLC; EVA MANAGEMENT LLC; ERIC GOODMAN REALTY CORP.; 308 E 90TH ST. LLC; ROSA MAGIAFREDDA; NEW GOLDEN AGE REALTY INC., d/b/a CENTURY 21 NEW GOLDEN AGE REALTY, INC.; CHAN & SZE REALTY INCORPORATED; PETER Case No. 21-cv-2221 CHRIS MESKOURIS; HELL’S KITCHEN, INC.; MYEROWTZ/SATZ REALTY CORP.; PD PROPERTIES LLC; ECF Case SMART MERCHANTS INCORPORATED; COLUMBUS NY REAL ESTATE INC.; LIONS GATE NEW YORK LLC; MATTHEW GROS WERTER; 780 RIVERSIDE OWNER LLC; ATIAS ENTERPRISES INC.; PARK ROW (1ST AVE.) LTD.; VORO LLC; PSJ HOLDING LLC; WINZONE REALTY INC.; CAMBRIDGE 41-42 OWNERS CORP.; RAY-HWA LIN; JANE H. TSENG; ALEXANDER HIDALGO REAL ESTATE, LLC; EAST 89th ASSOCIATES, LLC; PALEY MANAGEMENT CORP.; MAYET REALTY CORP.; NATURAL HABITAT REALTY INC.; CHELSEA 251 LLC; HOME BY CHOICE LLC; HAMILTON HEIGHTS ASSOCIATES, LLC; JRL-NYC, LLC; EAST 34TH STREET, LLC; BRITTBRAN REALTY, Case 1:21-cv-02221 Document 1 Filed 03/15/21 Page 2 of 64 LLC; MANHATTAN REALTY GROUP; WEGRO REALTY CO; JM PRESTON PROPERTIES, LLC; 1369 FIRST AVENUE, LLC; 931-955 CONEY ISLAND AVE. LLC; BEST MOVE REALTY; FORTUNE GARDENS, INC.; URBAN REAL ESTATE PROPERTY GROUP, INC.; 348 EAST 62ND LLC; JAN REYNOLDS REAL ESTATE; 83RD STREET ASSOCIATES LLC; FIRSTSERVICE REALTY NYC, INC.; TENTH MANHATTAN CORP.; 3LOCATION3.CO REALTY, LLC; 469 CLINTON AVE REALTY LLC; 718 REALTY INC.; DOUBLE A PROPERTY ASSOCIATES – CRESTION ARMS LLC; GUIDANCE REALTY CORP.; COL, LLC; BEST SERVICE REALTY CORP.; CHANDLER MANAGEMENT, LLC; MTY GROUP, INC.; 165TH ST. -

New York CITY

New York CITY the 123rd Annual Meeting American Historical Association NONPROFIT ORG. 400 A Street, S.E. U.S. Postage Washington, D.C. 20003-3889 PAID WALDORF, MD PERMIT No. 56 ASHGATENew History Titles from Ashgate Publishing… The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir The Long Morning of Medieval Europe for the Crusading Period New Directions in Early Medieval Studies Edited by Jennifer R. Davis, California Institute from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh. Part 3 of Technology and Michael McCormick, The Years 589–629/1193–1231: The Ayyubids Harvard University after Saladin and the Mongol Menace Includes 25 b&w illustrations Translated by D.S. Richards, University of Oxford, UK June 2008. 366 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6254-9 Crusade Texts in Translation: 17 June 2008. 344 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-4079-0 The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt Edited by Robert Bork, University of Iowa (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale and Andrea Kann AVISTA Studies in the History de France, MS Fr 19093) of Medieval Technology, Science and Art: 6 A New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile Includes 23 b&w illustrations with a glossary by Stacey L. Hahn October 2008. 240 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-6307-2 Carl F. Barnes, Jr., Oakland University Includes 72 color and 48 b&w illustrations November 2008. 350 pages. Hbk. 978-0-7546-5102-4 The Medieval Account Books of the Mercers of London Patents, Pictures and Patronage An Edition and Translation John Day and the Tudor Book Trade Lisa Jefferson Elizabeth Evenden, Newnham College, November 2008. -

455-467 E 155TH STREET 4-STORY CORNER BUILDING + PARKING Includes Garage with Drive-In Basement 455-467 EAST 155TH STREET - PROPERTY OVERVIEW

BRONX, NY 455-467 E 155TH STREET 4-STORY CORNER BUILDING + PARKING Includes Garage With Drive-in Basement 455-467 EAST 155TH STREET - PROPERTY OVERVIEW Property Description: Cushman and Wakefield has been retained on an exclusive basis to arrange for the sale of 455-467 East 155th Street, a 4-story building located on the North East corner of Elton Avenue and East 155th Street. Located in the Melrose neighborhood of the Bronx, the building is approximately 11,200 square feet with three massive 2,800 SF vacant floors on the 2nd through 4th floors. The second, third, and fourth floors have all been gutted with the second floor being completely renovated, providing new ownership with the ability to subdivide and create additional revenue. The sale also includes a garage located at 467 East 155th Street, which features a curb-cut and provides drive-in access to the basement of 455 East 155th Street. The property is located just a few blocks from ‘The Hub,’ also known as the ‘Time Square of the Bronx,’ providing immediate access to many national retailers and the 3rd Ave – 149th Street subway station. Serviced by both the @ & % subway lines, the station provides commuters a 23-minute subway ride to Grand Central Terminal. Offering a central location, flexibility of use, and significant upside, 455-467 East 155th Street stands out as an exceptional Bronx opportunity. Highlights: • 3 out of 4 floors are vacant • Long term ownership • 2nd Floor completely renovated • The property has a certificate of occupancy for office, storage and garage. -

Portnyc Developing the City's Freight and Passenger Infrastructure To

New York Harbor is the third-largest port in the United States and the largest port complex on the Atlantic Coast. New York City Economic Development Corporation’s PortNYC develops the City’s freight and passenger transportation infrastructure to strengthen the region’s economic growth. PortNYC facilities include marine cargo terminals, rail facilities, cruise terminals, ferry landings, active maritime piers, vessel berthing opportunities, and aviation facilities within New York City’s five boroughs. Marine Cargo Terminals New York City’s ports are America’s gateway to the largest and wealthiest consumer market in the United States. PortNYC supports the local economy by enabling firms to bring goods to market by vessel, one of the most efficient modes of freight transportation. Approximately 400,000 containers move through New York City’s seaports annually, and recent infrastructure upgrades to the city’s marine cargo terminals will allow more than a million tons of cargo to arrive by water instead of truck. The City promotes and incentivizes the maritime industry by maintaining and leasing these facilities and designating them Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas. CARGO FACILITIES • Global Container Terminal—New York (containers, break-bulk, and ro-ro), Staten Island • Red Hook Container Terminal (containers, break-bulk, and ro-ro), Brooklyn • South Brooklyn Marine Terminal (break-bulk, ro-ro, and project cargoes), Brooklyn Global Container Terminal on Staten Island is • 25th Street Freight Pier (aggregate), Brooklyn the city’s largest deep-sea marine facility. New York City is a maritime hub for support services hosting tugs, barges, and major ship repair facilities. NYC recently invested $115 million to reactivate marine and rail cargo facilities on the South Brooklyn waterfront. -

116Th Street (Cb10)

116TH STREET (CB10) Corridor Safety Improvements December 2016 PROJECT LOCATION . Part of safety improvements proposed on 116th St between Lenox Ave and Madison Ave . Busy corridor with residential and commercial land uses and several schools, children’s programs, senior centers, religious institutions nearby . 2/3 subway stop at Lenox Ave and nearby 6 subway stop at Lexington Ave . Many buses use 116th St: . Local buses: M116, M7, M102, M1 . Express buses: BxM6, BxM7, BxM8, BxM9, BxM10, BxM11 2 3 CB10 CB11 6 nyc.gov/dot 2 VISION ZERO PRIORITY W 116TH ST & Manhattan Priority Geographies LENOX AVE is a Vision Vision Zero Zero Priority • Multi-agency effort to reduce Intersection traffic fatalities in NYC • Borough Action Plans released in 2015 • Priority Intersections, Corridors, and Areas identified for each borough • On 116th St: • Intersections with Lenox Ave and Madison Ave identified as a Priority Intersections nyc.gov/dot 3 SAFETY DATA: PROJECT NEED W 116th St (Lenox Ave to 5th Ave): • 8 people severely injured (e.g., traumatic injuries typically requiring ambulance response) • 21 pedestrians injured at Lenox • 87 total injuries Total Injuries 2010-2014 42 3 Total KSI 35 KSI = persons 2010-2014 killed or severely 5 injured nyc.gov/dot 4 W 116TH ST & LENOX AVE: EXISTING CONDITIONS Long crossing distances for pedestrians, especially for seniors and children Lenox Ave is 80 feet wide Lenox Ave at W 116th St, looking south nyc.gov/dot 5 W 116TH ST & LENOX AVE: EXISTING CONDITIONS Pedestrians get stuck in the middle with no safe space -

Full Board Meeting

C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan RESOLUTION Date: May 5, 2015 Committee of Origin: Transportation Re: Broadway and West 103rd Street. Full Board Vote: 33 In Favor 0 Against 1 Abstention 0 Present Committee: 10-0-0-0. Non-Committee Board Members 2-0-0-0. Norman Rockwell was born and lived at 206 West 103rd Street where he began his career as an artist, yet another example of how Westsiders helped shape the arts/literary world. THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/Manhattan approves request by the Edward J. Reynolds School to name secondarily the Southeast corner of Broadway and West 103rd Street “Norman Rockwell Place.” 250 West 87th Street New York, NY 10024-2706 Phone: (212) 362-4008 Fax:(212) 595-9317 Web site: nyc.gov/mcb7 e-mail address: [email protected] C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan RESOLUTION Date: May 5, 2015 Committee of Origin: Transportation Re: Manhattanhenge. Full Board Vote: 34 In Favor 0 Against 1 Abstention 0 Present Committee: 10-0-0-0. Non-Committee Board Members 2-0-0-0. Manhattanhenge is a unique New York experience. THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED THAT Community Board 7/Manhattan approves the application to the Mayor’s Street Activity Permit Office for the street closure of West 79th Street (Columbus-Amsterdam Avenues) for the Manhattanhenge event on Monday, July 13th, 2015. 250 West 87th Street New York, NY 10024-2706 Phone: (212) 362-4008 Fax:(212) 595-9317 Web site: nyc.gov/mcb7 e-mail address: [email protected] C O M M U N I T Y B O A R D 7 Manhattan RESOLUTION Date: May 5, 2015 Committee of Origin: Transportation Re: School Crossing Guards.