Gentrifying Crown Heights by Marlon Peterson (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAS20 Sponsor Deck-091620-V2.6

Across the spectrum from young people to elders, Brooklyn Community Pride Center enables our community to actively participate in positive, life-affirming activities. We offer a distinctive choice for residents of New York City’s largest borough to celebrate, heal, learn, create, organize, relax, socialize, and play. Last year, we assisted over 10,000 unique visitors or contacts from the community, with more and more people stopping by every day. In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we moved most of our programs and services online. During the first three months of the pandemic, we saw as many virtual clients as we saw in-person visitors during the preceding nine months. We expect to see this growth in services continue to grow as we adapt to blended virtual and in-person programming. 75% of all unrestricted money raised is put into program services. 21% supports administration and operation with 4% into development efforts. The Community Leadership Awards recognize people and organizations who have made significant contributions to the LGBTQ+ community of Brooklyn. Recent honorees include: Abdul Muid, Founder and Principal of Ivey North; Ryann Holmes of bklyn boihood; dapperQ; Eric Adams, Brooklyn Borough President; Chubb; Jasmine Thomas, Citi Community Development; Marty Markowitz, former Brooklyn Borough President; and more. This year, in response to the pandemic, the awardees will be celebrated through a series of professionally produced videos distributed through social media backed by paid digital promotion. These videos will be short and social media friendly, with a conversational tone, and will highlight the impact the award recipient has had on Brooklyn’s LGBTQ+ community. -

Elected-Affiliated Nonprofits: Closing the Public Integrity Gap Richard Briffault1

February 10, 2021 draft Elected-Affiliated Nonprofits: Closing the Public Integrity Gap Richard Briffault1 I. Introduction In December 2013, shortly after winning election as New York City’s mayor – and some weeks before he was sworn into office – Bill de Blasio announced the formation of a “star-studded” public relations campaign that would help him secure the New York state legislature’s support for the funding of a centerpiece of his successful election campaign – universal pre-kindergarten for New York City’s children. The campaign would be run by a newly formed § 501(c)(4) tax-exempt corporation – the Campaign for One New York (CONY) -- which would raise donations from individuals, corporations, unions, and advocacy organizations to build public support and lobby Albany for “universal pre-K.”2 Over the next two-and-one-half years, CONY raised and spent over four million dollars, initially in support of universal pre-K, and then, after that goal was achieved, to promote another plank in the mayor’s 2013 campaign platform – changes to the city’s land use and zoning rules to increase affordable housing. The mayor played an active role in fund- raising for CONY, which received huge donations from real estate interests, unions and other groups that did business with the city, and he participated in its activities, including 1 Joseph P. Chamberlain Professor of Legislation, Columbia University School of Law. The author was chair of the New York City Conflicts of Interest Board (COIB) during some of the time period addressed in this article. The facts discussed in this article are drawn entirely from public reports and do not reflect any information the author gained from his COIB service. -

Sunset Park South Historic District

DESIGNATION REPORT Sunset Park South Historic District Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission Sunset Park South LP-2622 Historic District June 18, 2019 ESSAY RESEARCHED AND WRITTEN BY Michael Caratzas and Jessica Baldwin BUILDING PROFILES MaryNell Nolan-Wheatley, Margaret Herman, Theresa Noonan, and Michael Caratzas ARCHITECTS’ APPENDIX COMPLIED BY Marianne S. Percival EDITED BY Kate Lemos McHale PHOTOGRAPHS BY Sarah Moses and Jessica Baldwin COMMISSIONERS Sarah Carroll, Chair Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Diana Chapin Wellington Chen Michael Devonshire Michael Goldblum John Gustafsson Anne Holford-Smith Jeanne Lutfy Adi Shamir-Baron LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Mark Silberman, General Counsel Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission Sunset Park South LP-2622 Historic District June 18, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT Sunset Park South Historic District LOCATION Borough of Brooklyn LANDMARK TYPE Historic District SIGNIFICANCE Consisting almost entirely of two-story row houses built between 1892 and 1906, Sunset Park South is a remarkably cohesive historic district representing the largest collection of well-preserved row houses in Sunset Park, containing several of the neighborhood’s most distinctive streetscapes, and recalling Sunset Park’s origins and history as a middle-class community. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 513 Commission -

3550 North Lakeline Blvd, Leander, Texas

Brooklyn’s Pizza Sauces Famous tomato sauce Fresh basil pesto sauce White pizza (olive oil and garlic) Giant Pizza by the Slice - 4.50 cheese - .75 each additional topping (excluding specialty toppings) Traditional Cheese Pizza - Our tomato sauce and whole milk mozzarella cheese Medium (12”) - 9.99 - Large (16”) - 12.99 White Pizza - Extra virgin olive oil, fresh minced garlic and mozzarella cheese; no tomato sauce Medium (12”) - 9.99 - Large (16”) - 12.99 Basil Pesto Pizza - Fresh basil pesto and mozzarella cheese Medium (12”) - 10.99 Large (16”) - 13.99 28” Party Pizza with Cheese 35.00 (5.00 each additional topping) 14” Gluten Free Pizza Dough - 12.99 Choice Toppings: Medium* 1.50 / Large 2.00 Pepperoni • Italian Sausage • Smoked Ham • Hamburger • Black Olive • Green Olive • Pineapple • Marinated Tomato • Extra Mozzarella White Onions • Bell Peppers • Fresh Garlic • Mushrooms • Banana Pepper • Jalapeños • Red Onions • Extra Sauce RISTORANTE Gourmet Toppings: Medium 2.00 / Large 2.50 Chicago Italian Meatballs • Genoa Salami • Chicken • Lamb/Beef Gyro • Spicy Sicilian Sausage • Portobello Mushrooms • Roasted Red Peppers Artichoke Heart • Cilantro • Kalamata Olives • Real Bacon • Sun-Dried Tomato • Roma Tomato • Spinach PIZZERIA Specialty Toppings Medium 2.25 / Large 3.25 Anchovies • Feta Cheese • Gorgonzola • Fresh Mozzarella Specialty Pizzas MauiWowee - Smoked ham & pineapple 13.99 - 17.99 Let us cater your next event or party Margaritaville - Roma tomatoes, fresh mozzarella, parmesan-reggiano, fresh basil & herbs 15.99 - 20.99 call: -

Eric Adams' Message of the Month

ERIC ADAMS MESSAGE DIGITAL BROOKLYN BOROUGH PRESIDENT OF THE MONTH EDITION GUN VIOLENCE Must STOP! Symbolic shoes, in honor of one- year-old shooting victim Davell Gardner, Jr. WWW.BROOKLYN-USA.ORG AUGUST 2020 A MESSAGE FROM THE BOROUGH PRESIDENT BP Adams Davell Gardner Jr. Gun Violence Press Conference ENOUGH IS ENOUGH! The recent confirmation by the New York City Police York City. We must establish a regional gun task force to Department (NYPD) that, by the end of July, New York end, once and for all, the Iron Pipeline that is responsible City had surpassed the total number of shootings that for an estimated two-thirds of all criminal activity with guns. occurred in all of 2019, should be an issue of great And we must rebuild the strained relationship between concern to all who live in our city and this borough. These police and the community to ensure that real partnerships nearly 800 incidents of gun violence present stark proof lead to real change in our neighborhoods. But at the core of the depraved action of shooters that have resulted in of all this is the need for the blatant disregard for human the death, injury, and devastation experienced by victims life--exemplified by those perpetrating the crimes, and by and their families in an alarming cycle of brutality and those who know the culprits pulling the trigger, but who lawlessness. fail to come forward to offer information that could help authorities stem the violence plaguing our families and our Perhaps the most heartbreaking and senseless case was neighbors—to end, ultimately saving lives. -

The { 2 0 2 1 N Y C } »G U I D E«

THE EARLY VOTING STARTS JUNE 12 — ELECTION DAY JUNE 22 INDYPENDENT #264: JUNE 2021 { 2021 NYC } ELECTION » GUIDE« THE MAYOR’S RACE IS A HOT MESS, BUT THE LEFT CAN STILL WIN BIG IN OTHER DOWNBALLOT RACES {P8–15} LEIA DORAN LEIA 2 EVENT CALENDAR THE INDYPENDENT THE INDYPENDENT, INC. 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11217 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org Twitter: @TheIndypendent facebook.com/TheIndypendent SUE BRISK BOARD OF DIRECTORS Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, Alina Mogilyanskaya, Ann tions of films that and call-in Instructions, or BRYANT PARK SPIRIT OF STONEWALL: The Schneider, John Tarleton include political, questions. RSVP by June 14. 41 W. 40th St., third annual Queer Liberation March will be pathbreaking and VIRTUAL Manhattan held Sunday June 27. EDITOR-IN-CHIEF JUNE visually inspir- John Tarleton ing selections. JUNE 18–20 ONGOING JUNE 4–20 The theater will JUNETEENTH NY FESTIVAL • 8AM–5PM • FREE Lincoln Center is opening a CONTRIBUTING EDITORS TIME & PRICE (EST. $50) TBD. continue to offer virtual FREE OUTDOORS: SHIRLEY CH- giant outdoor performing Ellen Davidson, Alina POP UP MAGAZINE: THE SIDE- cinema for those that don’t yet Juneteenth NYC’s 12th ISHOLM STATE PARK arts center that will include Mogilyanskaya, Nicholas WALK ISSUE feel comfortable going to the annual celebration starts on Named in honor of a Brooklyn- 10 different performance and Powers, Steven Wishnia This spring, the multimedia movies in person. Friday with professionals and born trailblazer who was the rehearsal spaces. Audience storytelling company Pop-Up BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF residents talking about Health fi rst Black congresswoman, members can expect free and ILLUSTRATION DIRECTOR Magazine takes to the streets. -

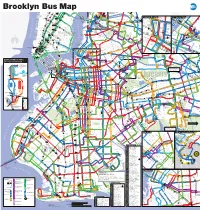

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

NEW YORK CITY DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY Interview Schedule

NEW YORK CITY DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY Interview Schedule May 14-17, 2021 Project: 210119 N=500 potential Democratic primary voters in NYC Margin of Error: +4.38% D4E. And, regardless of how you currently feel about politics and current events, in which party are you REGISTERED to vote? Republican, Democrat, Independence Conservative Working Families Something else or are you not enrolled in any party? 71% STRONG DEMOCRAT 29% NOT-SO-STRONG DEMOCRAT D. And, how likely would you say you are to vote in the June Democratic primary election for Mayor and other local offices? Are you... 88% VERY LIKELY 12% SOMEWHAT LIKELY 1. Generally speaking, would you say that things in New York City are going in the right direction, or have they pretty seriously gotten off on the wrong track? 45% RIGHT DIRECTION 45% WRONG TRACK 8% DON'T KNOW 2% REFUSED New York City Democratic Primary Survey Page 2 of 17 Interview Schedule 2. Do you approve or disapprove of the job that Bill de Blasio is doing as Mayor of New York City? 8% STRONGLY APPROVE 27% SOMEWHAT APPROVE 30% SOMEWHAT DISAPPROVE 29% STRONGLY DISAPPROVE 5% DON'T KNOW 1% REFUSED 35% TOTAL APPROVE 59% TOTAL DISAPPROVE 3. Do you approve or disapprove of the job the New York City Police Department is doing? 18% STRONGLY APPROVE 32% SOMEWHAT APPROVE 21% SOMEWHAT DISAPPROVE 25% STRONGLY DISAPPROVE 3% DON'T KNOW 2% REFUSED 50% TOTAL APPROVE 45% TOTAL DISAPPROVE 4. Do you approve or disapprove of the job that Andrew Cuomo is doing as Governor of New York? 35% STRONGLY APPROVE 36% SOMEWHAT APPROVE 12% SOMEWHAT DISAPPROVE 15% STRONGLY DISAPPROVE 2% DON'T KNOW 1% REFUSED 71% TOTAL APPROVE 26% TOTAL DISAPPROVE New York City Democratic Primary Survey Page 3 of 17 Interview Schedule Now, I would like to read you several names of different people active in politics. -

View the Full Poll Results and Methodology

TOPLINE & METHODOLOGY Spectrum News NY1/Ipsos NYC Mayoral Primary Poll Conducted by Ipsos using KnowledgePanel® A survey of NYC Residents (ages 18+) April 20, 2021 Release Interview dates: April 1 – April 15, 2021 Number of interviews: 3,459 Number of interviews among Democratic likely voters: 1,000 Credibility interval: +/-2.5 percentage points at the 95% confidence level Credibility interval among likely Democratic primary voters: +/- 4.7 NOTE: All results show percentages among all respondents, unless otherwise labeled. Reduced bases are unweighted values. NOTE: * = less than 0.5%, - = no respondents Annotated Questionnaire: S3. Which borough do you live in? Likely Total Voters The Bronx 16 16 Brooklyn 30 28 Manhattan 21 26 Queens 27 26 Staten Island 5 4 Skipped - - S4. Do you have children in the following age groups in your household? Likely Total Voters Under 5 years old 9 10 5 to 12 years old 18 18 13 to 17 years old 12 15 18 or older 24 24 I do not have any children in my 49 49 household Skipped * * TOPLINE & METHODOLOGY 1. Which of the following do you consider to be the main problems facing New York today? You may select up to two. Total Likely Voters COVID-19/coronavirus 49 51 Crime or violence 39 39 Affordable housing 28 37 Racial injustice 23 27 Unemployment 21 18 Gun control 16 21 Taxes 14 11 Education 12 12 Healthcare 11 12 Transportation/infrastructure 10 14 Police reform 9 11 Opioid or drug addiction 8 7 Climate change/natural disasters 7 8 Immigration 6 4 Other 2 3 None of these 2 2 Skipped * - 2. -

Narrative Summary of Constraints and Opportunities Provided to the Panel by NYC DOT

As presented to the BQE Expert Panel for informational/background purposes only https://bqe-i278.com/en/expert-panel/documents Narrative Summary of Constraints and Opportunities Provided to the panel by NYC DOT What Makes the Project So Complicated? Fixing the BQE is exceptionally complicated due to its unusual design and the constrained site in which it operates. This corridor is sandwiched between Brooklyn Bridge Park, the Promenade and Brooklyn Heights, the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, bustling DUMBO and Vinegar Hill, and an extraordinary volume of infrastructure below – four subway lines, an eight-foot DEP interceptor sewer, and many other utility lines. Creating sufficient space to stage the construction (e.g. to fit equipment like cranes and store materials) is a key challenge that any concept must address. Specifically, any construction concept needs to account for the complexities of working with a cantilever structure, building on or around Furman Street, the surrounding open spaces, and other infrastructure running above and below the BQE. This part of the BQE corridor is also comprised of multiple structures that require different methods of rehabilitation or replacement. Although the triple cantilever is the most well-known portion of this project, the double cantilever and the bridges at Joralemon, Old Fulton, and Columbia Heights all require repair. Cantilever Considerations A traditional bridge structure is usually rehabilitated lane-by-lane. Construction crews shut down a portion of the bridge, repair those areas, and then shift traffic to the rehabilitated section. This type of construction staging is not possible on the triple cantilever due to the unique nature of the BQE. -

Cop Saves Woman from Slope Rapist

GARCIA MAKES METS AS CLONES CLINCH BACK PAGE INSIDE BROOKLYN’S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER Including The Downtown News, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper Painters take on avant-garde Published weekly by Brooklyn Paper Publications at 26 Court St., Brooklyn, NY 11242 Phone 718-834-9350 © Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol.26, No. 36 BWN • September 8, 2003 • FREE Cop saves woman from Slope rapist By Patrick Gallahue thug took off and Ward chased him and tack- instinct was to go over and chase the perp Bridge. A suspect was arrested in the incident. The Brooklyn Papers led him near Prospect Park West. down,” said Deputy Inspector Edward On July 10, a 45-year-old woman was at- The suspect, Bennie Hogan, 39, of Browns- Mullen, commanding officer of the 78th tacked at Lookout Hill, inside the park off A quick-thinking police officer chased ville, has been charged with attempted rape, as- Precinct. Prospect Park South and Terrace Place, at down a career criminal and convicted sex sault and resisting arrest. The scooter was purchased for the precinct around 10:45 am. offender on the Park Slope side of The beaten and bloodied victim was taken last Christmas by Park Slope Councilman Bill The assailant was scared off by another Prospect Park on Tuesday after the sus- to Kings County Medical Center where she DeBlasio using discretionary funds allocated jogger as the victim tried to fight off her at- pect allegedly attempted to rape a 33-year- was treated for severe cuts and bruises. -

Summer Camp Guide 2018 Summer Camps Easily Accessible from Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, Bococa and Beyond

Summer Camp Guide 2018 Summer camps easily accessible from Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, BoCoCa and beyond This comprehensive summer camp guide profiles 50 local summer camps in Brooklyn Heights, DUMBO, Downtown Brooklyn, Gowanus, BoCoCa and beyond! We have listed program details, age groups, dates, hours, costs and contact information for each camp for children 18 months to 18 years old. The guide includes arts, animation, circus, cooking, engineering, fashion design, movie making, swimming, skateboarding, tennis, theater, STEM, and textile camps. It also features French, Spanish, Hebrew, Italian and Mandarin immersion summer programs in our neighborhood and much more! Animation & Music Camp Program: In our Stop Motion Animation camp young creators ages 5-9 will learn and create original animation movies and engage in activities designed to cultivate curiosity, creativity, self- expression and friendship. They are guided through the steps of producing movies with cool themes, titles, sound effects and a whole host of unique features and work with variety of materials to create their stop-motion’s objects, sets, figures, props, sequential drawing or animate toys. Our enriching summer experience is designed so that children additionally to movie making explore sound, music, drumming, martial arts and other activities indoor and outdoor including a daily recess at the John Street lawn in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Small group limited to 6 campers a day. Students are required to bring their own iPad or iPhone to camp with the appropriate