The National Media Lost Interest Almost Immediately, Horse Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commonwealth Magazine a Project of the Economic Prosperity Initiative DONAHUE INSTITUTE

FADING BLUE COLLARS • CIVIL DISSERVICE • ASSET VALUES CommonWealthCommonWealthPOLITICS, IDEAS, AND CIVIC LIFE IN MASSACHUSETTS THETHE URBAN URBAN HIGHHIGH SCHOOLSCHOOL THATTHAT WORKS WORKS DAVID OSBORNE:OSBORNE: BUILDING AA BETTERBETTER STATE BUDGETBUDGET SPRING 2004 $5.00 PLUS—STATES OF THE STATES University Park Campus School, in Worcester AA ChanceChance toto AAchievechieve Their Dreams This year, more than 720 non-traditional adult learners who face barriers to academic success will have an opportunity to earn a college degree. Through the New England ABE-to-College Transition Project, GED graduates and adult diploma recipi- ents can enroll at one of 25 participating adult learning centers located across New England to take free college preparation courses and receive educational and career planning counseling.They leave the pro- gram with improved academic and study skills, such as writing basic research papers and taking effective notes. Best of all, they can register at one of 30 colleges and universities that partner with the program. Each year, the Project exceeds its goals: 60 percent complete the program; and 75 percent of these graduates go on to college. By linking Adult Basic Education to post-secondary education,the New England ABE-to-College Transition Project gives non-traditional adult learners a chance to enrich their own and their families’ lives. To learn more, contact Jessica Spohn, Project Director, New England Literacy Resource Center, at (617) 482-9485, ext. 513, or through e-mail at [email protected]. (The Project is funded by the Nellie Mae Education Foundation through the LiFELiNE initiative.) 1250 Hancock Street, Suite 205N • Quincy, MA 02169-4331 Tel. -

Progressive Massachusetts 2020 Congressional

PROGRESSIVE MASSACHUSETTS 2020 CONGRESSIONAL ENDORSEMENT QUESTIONNAIRE Date: 2/10/2020 Candidate: Alan Khazei th Office Sought: Massachusetts 4 Congressional District Party: Democrat Website: www.alankhazei.com Twitter: @AlanKhazei Facebook: www.facebook.com/khazeiforcongress Other Social Media: Instagram - @AlanKhazei Email questions to [email protected]. preference/identity, and ability. I expect to win by engaging voters through the passions that inspire I. About You 1. Why are you running for office? And what will your top 3 priority pieces of legislation if elected? I’m running for Congress in Massachusetts for several reasons. First as a parent, I don’t want to be part of the first generation since the founding of our country to leave the country worse off to our children and grandchildren than our parents and grandparents left it for us. Second, because I believe that we are in the worst of times but also best of times for our democracy. Worst because Trump is an existential threat to our values, principles, ideals and pillars of our democracy. But best of times, because of the extraordinary new movement energy that has emerged. I’ve been a movement leader, builder and activist my entire career and I’m inspired by the new energy. I’ve been on the outside building coalitions to get big things done in our nation, but now want to get on the inside, bust open the doors of Congress and bring this new movement energy in to break the logjam in DC. Third, I am a service person at my core. Serving in Congress is an extraordinary opportunity to make a tangible and daily difference in people’s lives. -

Ellen L. Weintraub

2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Home › About the FEC › Leadership and Structure › All Commissioners › Ellen L. Weintraub Ellen L. Weintraub Democrat Currently serving CONTACT Email [email protected] Twitter @EllenLWeintraub Biography Ellen L. Weintraub (@EllenLWeintraub) has served as a commissioner on the U.S. Federal Election Commission since 2002 and chaired it for the third time in 2019. During her tenure, Weintraub has served as a consistent voice for meaningful campaign-finance law enforcement and robust disclosure. She believes that strong and fair regulation of money in politics is important to prevent corruption and maintain the faith of the American people in their democracy. https://www.fec.gov/about/leadership-and-structure/ellen-l-weintraub/ 1/23 2/5/2020 FEC | Commissioner Ellen L. Weintraub Weintraub sounded the alarm early–and continues to do so–regarding the potential for corporate and “dark-money” spending to become a vehicle for foreign influence in our elections. Weintraub is a native New Yorker with degrees from Yale College and Harvard Law School. Prior to her appointment to the FEC, Weintraub was Of Counsel to the Political Law Group of Perkins Coie LLP and Counsel to the House Ethics Committee. Top items The State of the Federal Election Commission, 2019 End of Year Report, December 20, 2019 The Law of Internet Communication Disclaimers, December 18, 2019 "Don’t abolish political ads on social media. Stop microtargeting." Washington Post, November 1, 2019 The State of the Federal Election -

Post-Gazette 12-4-09 Pqm.Pmd

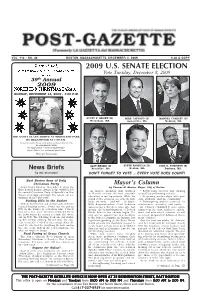

VOL. 113 - NO. 49 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, DECEMBER 4, 2009 $.30 A COPY 2009 U.S. SENATE ELECTION Vote Tuesday, December 8, 2009 39th Annual 2009 SUNDAY, DECEMBER 13, 2009 - 1:00 P.M. SCOTT P. BROWN (R) MIKE CAPUANO (D) MARTHA COAKLEY (D) Wrentham, MA Somerville, MA Medford, MA SEE SANTA CLAUS ARRIVE AT NORTH END PARK BY HELICOPTER AT 1:00 P.M. In case of bad weather, Parade will be held the next Sunday, December 20th IN ASSOCIATION WITH The Nazzaro Center • North End Against Drugs • Mayor’s Offi ce of Arts, Tourism and Special Events Merry Christmas ALAN KHAZEI (D) STEVE PAGLIUCA (D) JACK E. ROBINSON (R) News Briefs Brookline, MA Weston, MA Duxbury, MA by Sal Giarratani DON’T FORGET TO VOTE ... EVERY VOTE DOES COUNT! East Boston Sons of Italy Christmas Party Mayor’s Column Don’t forget Sunday, December 6 when the by Thomas M. Menino, Mayor, City of Boston East Boston Sempre Avanti Lodge #1600 holds As mayor, assuring that children • Replicating success and turning its annual Christmas Party at Spinelli’s in Day in Boston receive the best possible around low-performing schools Square from 2pm until 6pm. For tickets call Joe education is my top priority. While I’m • Deepening partnerships with par- Guarino at 617-569-3405. proud of the progress our schools have ents, students, and the community Putting IOUs in the Basket made, we must — and will — do better. • Redesigning district services for Only in East Boston and at Our Lady of Mount With Superintendent Carol Johnson effectiveness, efficiency, and equity Carmel (Sunday service, 10am) can one put an announcing a five-year plan late last Dr. -

Welcome to the New England Circle/Citizens Roundtable. This Evening's Discussion, Affirmative Action and Its Impact on Society Is Led by JUDGE A

OMNI PARKER HOUSE BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS APRIL 25,1995 Welcome to the New England Circle/Citizens Roundtable. This evening's discussion, Affirmative Action and Its Impact on Society is led by JUDGE A. LEON HIGGINBOTHAM JR. Professor of Jurisprudence at The John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Until he retired in 1993, Judge Higginbotham served as Circuit Judge and as Chief Judge Emeritus of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. He was appointed a district court judge in 1964 and a court of appeals judge in 1977. In addition, he has many years of experience as an attorney, and he held numerous teaching appointments at such universities as the University of Pennsylvania, New York University and Harvard Law School. His book, In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process, was published in 1978 with the hope that "...this volume will help us better understand the history we cannot escape and cause us to assume the responsibility we owe to our future." Judge Higginbotham is a graduate of Anitoch College and Yale Law School, as well as the recipient of more than 60 honorary degrees. He is married to Dr. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, a professor of African American Studies at Harvard. They reside in Newton, Massachusetts and have four children. This evening's moderator is MARTY LINSKY a counselor to Governor William Weld and adjunct lecturer at the John F. Kennedy School of Government. He came to the Governor's office from the Kennedy School, where he was a full-time faculty member teaching about press, leadership, politics, and public management. -

Big Dig $458.2 Million Global Agreement

Big Dig $458.2 Million Global Agreement State Agencies State A-Z Topics Skip to main content Need help resizing text? State Forms The Official Website of the Attorney General of Massachusetts Attorney General in Attorney General Martha Coakley About the Attorney Consumer Doing Business in Government News and Updates Public Safety Bureaus General's Office Resources Massachusetts Resources Home News and Updates Press Releases 2008 MARTHA COAKLEY For Immediate release - January 23, 2008 ATTORNEY GENERAL Big Dig Management Consultant and Designers To Pay $450 Million Media Contact Press Conference Audio and Supporting Documents Included Below Massachusetts Attorney General's Office: Emily LaGrassa (617) 727-2543 BOSTON - The joint venture of Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff, Bechtel Infrastructure Corp., and PB Americas, Inc., f/k/a Parsons U.S. Attorney's Office: Brinckerhoff Quade and Douglas, Inc. ("Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff"), the management consultant to the Central Artery/Tunnel Christina DiIorio-Sterling Project ("the Big Dig") has agreed to pay over $407 million to resolve its criminal and civil liabilities in connection with the collapse (617) 748-3356 of part of the I-90 Connector Tunnel ceiling and defects in the slurry walls of the Tip O'Neill tunnel. In addition, 24 Section Design Consultants-other contractors who worked on various parts of the project--have agreed to pay an additional $51 million to resolve certain cost recovery issues associated with the design of the Big Dig. In total, the United States and the Commonwealth will recover $458 million, including interest. United States Attorney Michael J. Sullivan, Massachusetts Attorney General Martha Coakley, Theodore L. -

![Marginals [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5315/marginals-pdf-735315.webp)

Marginals [PDF]

Suffolk University/7NEWS EMBARGO UNTIL 11PM 1/14/10 GEOC N= 500 100% Worcester/West ................................. 1 ( 1/ 86) 120 24% NE ............................................. 2 176 35% Suffolk ........................................ 3 39 8% SE Mass/Cape ................................... 4 165 33% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for 7NEWS/Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. Would you be willing to spend five minutes answering some questions? N= 500 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/ 88) 500 100% GENDR Gender N= 500 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/ 89) 240 48% Female ......................................... 2 260 52% S1 Thank You. S1. Are you currently registered to vote? N= 500 100% Yes ............................................ 1 ( 1/ 90) 500 100% NO/DK/RF ....................................... 2 0 0% SA A. How likely are you to vote in the Special Election for U.S. Senator - would you say you are very likely, somewhat likely, somewhat unlikely, or not at all likely? N= 500 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/ 93) 449 90% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 51 10% Somewhat unlikely .............................. 3 0 0% No at all likely ............................... 4 0 0% DK/RF .......................................... 5 0 0% SB B. Can you tell me when the Special Election for U.S. Senate will be held? N= 500 100% “January 19th” ................................. -

Panorama Adverso

CARTA QUINCENAL ENERO 2010 VOLUMEN 6 NÚMERO 14 .....................................................................1 Panorama adverso ................................................................................................... 1 La nueva política de seguridad estadounidense ...................................................... 2 ................2 Desde la Cancillería ................................................................................................ 2 XXI Reunión de Embajadores ........................................................................ 2 Homenaje al Embajador Carlos Rico .............................................................. 3 México ante la catástrofe en Haití .......................................................................... 3 ¿Una nueva etapa en Honduras? ............................................................................. 4 Conferencia de Copenhague: retos y resultados ..................................................... 5 México en el Consejo de Seguridad ........................................................................ 6 Los trabajos en la 64ª Asamblea General de la ONU ............................................. 7 Visita de Alberto Brunori a Chihuahua .................................................................. 8 .............................................9 La iniciativa sobre protección a periodistas ............................................................ 9 Senado crítica a SRE por mandar al director de la Lotería Nacional a la Embajada de México -

Becoming an Active Citizen: National Constitution Center Hosts Conversation with Harris Wofford and Alan Khazei

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Ashley Berke Alex McKechnie Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6693 215.409.6895 [email protected] [email protected] BECOMING AN ACTIVE CITIZEN: NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER HOSTS CONVERSATION WITH HARRIS WOFFORD AND ALAN KHAZEI Philadelphia, PA (October 29, 2010) – The National Constitution Center will highlight the importance of active citizenship during a roundtable discussion on Thursday, November 11, 2010 at 6:30 p.m., with Harris Wofford , former United States Senator, and Alan Khazei , author of the new book Big Citizenship: How Pragmatic Idealism Can Bring Out the Best in America . David L. Cohen , Executive Vice President of Comcast Corporation, will introduce the program, and David Eisner , President and CEO of the National Constitution Center, will moderate. In a political environment often bogged down by petty bickering and cynicism, the panelists will discuss ways to bridge differences, encourage positive discourse, and effect powerful change. Admission is FREE, but reservations are required and can be made by calling 215.409.6700 or at www.constitutioncenter.org . Harris Wofford represented the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1991 to 1994. He previously served as Governor Casey’s Secretary of Labor and Industry. Wofford was president of Bryn Mawr College from 1970 to 1978. In the 1960s, he served as President Kennedy’s Special Assistant for Civil Rights, and worked closely with Sargent Shriver in organizing the Peace Corps. Later, Wofford served as the Peace Corps’ Special Representative to Africa and its Associate Director. He is the author of five books, including Of Kennedys and Kings: Making Sense of the Sixties . -

Democrat Martha Coakley Vs. Republican Charlie Baker

Democrat Martha Coakley vs. Republican Charlie Baker Martha Charlie Issue Coakley Baker Has made universal access to early education a top priority, and has a specific plan to eliminate the early ed. waiting list ✔ ✖ Supports earned sick time for every worker, because no one should have to choose between their job and their health ✔ ✖ Opposes the death penalty ✔ ✖ Supported an $11/hour minimum wage and said an increase should not be tied to changes in our unemployment insurance ✔ ✖ system Has made expanding care for mental health and substance abuse a cornerstone of her campaign ✔ ✖ Has been on the front lines, fighting for the right of women to access reproductive healthcare ✔ ✖ Has strongly supported a ban on assault weapons ✔ ✖ Took on the big banks to keep 30,000 Massachusetts families in their homes ✔ ✖ Backs critical funding for our transportation system, which is crumbling after decades of underinvestment ✔ ✖ Has been a steadfast proponent of South Coast Rail, which will help unlock economic potential in communities like Fall River ✔ ✖ and New Bedford Supports the right of transgender individuals to access all places of public accommodation, free from harassment or intimidation ✔ ✖ Acknowledges the reality of climate change and has a specific plan to help us reduce our carbon footprint and preserve natural ✔ ✖ resources. Supports in state tuition for the children of undocumented immigrants ✔ ✖ Has an economic development plan that focuses on building from the ground up, not hoping that tax breaks for businesses ✔ ✖ will trickle down Has disavowed attack ads run by outside Super PACs ✔ ✖ Republican Charlie Baker: Choosing the Bottom Line over the People of Massachusetts When he had the chance, Republican Charlie Baker failed to respond to a growing crisis at DSS. -

Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21St Century (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2020)

OUR COMMON REINVENTING AMERICAN PURPOSEDEMOCRACY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY COMMISSION ON THE PRACTICE OF DEMOCRATIC CITIZENSHIP Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good. I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad. Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die. If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavor to gain partizans in support of them, we might prevent its being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects and great advantages resulting naturally in our favor among foreign Nations as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent unanimity. —BENJAMIN FRANKLIN FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE COMMISSION ON THE PRACTICE OF DEMOCRATIC CITIZENSHIP OUR COMMON REINVENTING AMERICAN PURPOSEDEMOCRACY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts © 2020 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-87724-133-3 This publication is available online at www.amacad.org/ourcommonpurpose. Suggested citation: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2020). PHOTO CREDITS iStock.com/ad_krikorian: cover; iStock.com/carterdayne: page 1; Martha Stewart Photography: pages 13, 19, 21, 24, 28, 34, 36, 42, 45, 52, -

March 2010 Stitutional Issues

2 revolving door: From m a r c h 2 0 1 0 Hauser Hall to the halls of D.C. New Public Service Venture Fund launched at HLS arvard support for graduating law school J.D. students who hope Hannounced in to pursue postgraduate February the creation work at nonprofits or of the Public Service government agencies in Venture Fund, which the United States and will start by awarding $1 abroad. million in grants every “This new fund year to help graduating is inspired by our This fund is an students pursue careers students’ passion for investment that H RT in public service. justice,” said Harvard will pay dividends O W The first program Law School Dean not only for our ns R A of its kind at a law Martha Minow. “It’s an students, but also F school, the fund will investment that will pay for the people phil offer “seed money” dividends not only for whose lives they JUDICIAL BRANCHES offered hints of spring ahead, as budding lawyers took for startup nonprofit our students, but also refuge from snow in the warmth of Langdell. will touch.” ventures and salary for the countless >>8 Dean Martha Minow Prosecution on the world stage Seminar explores policies of the ICC’s first prosecutor his january, in a war crimes and crimes against seminar taught by Dean humanity. Discussion ranged TMartha Minow and from the court’s approach to Associate Clinical Professor gender crimes and charging Alex Whiting, 15 students at policies, to the role of victims, Harvard Law School discussed and the power of what Minow the policies and strategies of the called “the shadow”—outside prosecutor of the International actors who magnify the court’s N TE Criminal Court.