Mediating Self-Representations: Tensions Surrounding 'Ordinary'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED for THE

Monday 7 January 2019 FULL CASTING ANNOUNCED FOR THE WEST END TRANSFER OF HOME, I’M DARLING As rehearsals begin, casting is announced for the West End transfer of the National Theatre and Theatr Clwyd’s critically acclaimed co-production of Home, I’m Darling, a new play by Laura Wade, directed by Theatre Clwyd Artistic Director Tamara Harvey, featuring Katherine Parkinson, which begins performances at the Duke of York’s Theatre on 26 January. Katherine Parkinson (The IT Crowd, Humans) reprises her acclaimed role as Judy, in Laura Wade’s fizzing comedy about one woman’s quest to be the perfect 1950’s housewife. She is joined by Sara Gregory as Alex and Richard Harrington as Johnny (for the West End run, with tour casting for the role of Johnny to be announced), reprising the roles they played at Theatr Clwyd and the National Theatre in 2018. Charlie Allen, Susan Brown (Sylvia), Ellie Burrow, Siubhan Harrison (Fran), Jane MacFarlane and Hywel Morgan (Marcus) complete the cast. Home, I’m Darling will play at the Duke of York’s Theatre until 13 April 2019, with a press night on Tuesday 5 February. The production will then tour to the Theatre Royal Bath, and The Lowry, Salford, before returning to Theatr Clwyd following a sold out run in July 2018. Home, I’m Darling is co-produced in the West End and on tour with Fiery Angel. How happily married are the happily married? Every couple needs a little fantasy to keep their marriage sparkling. But behind the gingham curtains, things start to unravel, and being a domestic goddess is not as easy as it seems. -

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee S4C Written evidence - web List of written evidence 1 URDD 3 2 Hugh Evans 5 3 Ron Jones 6 4 Dr Simon Brooks 14 5 The Writers Guild of Great Britain 18 6 Mabon ap Gwynfor 23 7 Welsh Language Board 28 8 Ofcom 34 9 Professor Thomas P O’Malley, Aberystwth University 60 10 Tinopolis 64 11 Institute of Welsh Affairs 69 12 NUJ Parliamentary Group 76 13 Plaim Cymru 77 14 Welsh Language Society 85 15 NUJ and Bectu 94 16 DCMS 98 17 PACT 103 18 TAC 113 19 BBC 126 20 Mercator Institute for Media, Languages and Culture 132 21 Mr S.G. Jones 138 22 Alun Ffred Jones AM, Welsh Assembly Government 139 23 Celebrating Our Language 144 24 Peter Edwards and Huw Walters 146 2 Written evidence submitted by Urdd Gobaith Cymru In the opinion of Urdd Gobaith Cymru, Wales’ largest children and young people’s organisation with 50,000 members under the age of 25: • The provision of good-quality Welsh language programmes is fundamental to establishing a linguistic context for those who speak Welsh and who wish to learn it. • It is vital that this is funded to the necessary level. • A good partnership already exists between S4C and the Urdd, but the Urdd would be happy to co-operate and work with S4C to identify further opportunities for collaboration to offer opportunities for children and young people, thus developing new audiences. • We believe that decisions about the development of S4C should be made in Wales. -

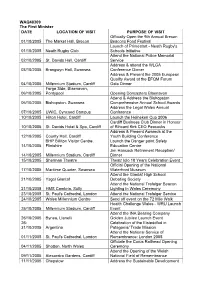

WAQ48309 the First Minister DATE LOCATION OF

WAQ48309 The First Minister DATE LOCATION OF VISIT PURPOSE OF VISIT Officially Open the 9th Annual Brecon 01/10/2005 The Market Hall, Brecon Beacons Food Festival Launch of Primestart - Neath Rugby's 01/10/2005 Neath Rugby Club Schools Initiative Attend the National Police Memorial 02/10/2005 St. Davids Hall, Cardiff Service Address & attend the WLGA 03/10/2005 Brangwyn Hall, Swansea Conference Dinner Address & Present the 2005 European Quality Award at the EFQM Forum 04/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Gala Dinner Forge Side, Blaenavon, 06/10/2005 Pontypool Opening Doncasters Blaenavon Attend & Address the Bishopston 06/10/2005 Bishopston, Swansea Comprehensive Annual School Awards Address the Legal Wales Annual 07/10/2005 UWIC, Cyncoed Campus Conference 10/10/2005 Hilton Hotel, Cardiff Launch the Heineken Cup 2006 Cardiff Business Club Dinner in Honour 10/10/2005 St. Davids Hotel & Spa, Cardiff of Rihcard Kirk CEO Peacocks Address & Present Awareds at the 12/10/2005 County Hall, Cardiff Youth Building Conference BHP Billiton Visitor Centre, Launch the Danger point Safety 14/10/2005 Flintshire Education Centre Jim Hancock Retirement Reception/ 14/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Dinner 15/10/2005 Sherman Theatre Theatr Iolo 18 Years Celebration Event Official Opening of the National 17/10/2005 Maritime Quarter, Swansea Waterfront Museum Attend the Glantaf High School 21/10/2005 Ysgol Glantaf Debating Society Attend the National Trafalgar Beacon 21/10/2005 HMS Cambria, Sully Lighting in Wales Ceremony 23/10/2005 St. Paul's Cathedral, London Attend the National Trafalgar Service 24/10/2005 Wales Millennium Centre Send off event on the 72 Mile Walk Health Challenge Wales - WRU Launch 25/10/2005 Millennium Stadium, Cardiff Event Attend the INA Bearing Company 26/10/2005 Bynea, Llanelli Golden Jubilee Launch Event 26- Celebration of the Eisteddfod in 31/10/2005 Argentina Patagonia/ Trade Mission Attend the National Service of 01/11/2005 St. -

BAFTA Cymru Nominations 2010

Yr Academi Brydeinig o Gelfyddydau Ffilm a Theledu Yng Nghymru Gwobrwyon Prif Noddwr The British Academy of Film and Television Arts in Wales Awards Principal Sponsor Enwebiadau 2010 eg 19 Gwobrau Ffilm Teledu A Chyfryngau Rhyngweithiol Nos Sul 23 Mai, Canolfan Mileniwm Cymru, Cardiff 2010 Nominations 19th Film, Television & Interactive Media Awards Sunday 23 May, Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff Y Ffilm/Drama Gorau Best Film/Drama Noddir Gan/Sponsored By A BIT OF TOM JONES? ANDREW "SHINKO" JENKINS / PETER WATKINS- HUGHES CWCW DELYTH JONES / BETHAN EAMES RYAN A RONNIE BRANWEN CENNARD / MARC EVANS Y Cyfres Ddrama Orau ar gyfer Teledu / Best Drama Series / Serial for Television DOCTOR WHO TRACIE SIMPSON THE END OF TIME PART ONE TORCHWOOD PETER BENNETT CHILDREN OF THE EARTH DAY ONE TEULU RHYS POWYS / BRANWEN CENNARD Y Newyddion a Materion Cyfoes Gorau / Best News & Current Affairs Noddir Gan/Sponsored By ONE FAMILY IN WALES JAYNE MORGAN / KAREN VOISEY PANORAMA JAYNE MORGAN SAVE OUR STEEL Y BYD AR BEDWAR GERAINT EVANS MEWNFUDWYR Contact: BAFTA Cymru T: 02920 223898 E: [email protected] Dydd Iau 8 Ebrill, 2010 W: www.bafta-cymru.org.uk Thursday 8 April, 2010 ENWEBIADAU 2010 NOMINATIONS Y Rhaglen Ffeithiol Orau Best Factual Programme COMING HOME 'JOHN PRESCOTT' PAUL LEWIS FIRST CUT: THE BOY WHO WAS BORN A GIRL JULIA MOON / JOHN GERAINT FRONTLINE AFGHANISTAN GARETH JONES Y Rhaglen Ddogfen / Ddrama Ddogfen Orau Best Documentary / Drama Documentary CARWYN DYLAN RICHARDS / JOHN GERAINT DWY WRAIG LLOYD GEORGE, GYDA FFION HAGUE CATRIN EVANS A PLOT TO KILL THE PRINCE STEFFAN MORGAN Yr Adloniant Ysgafn Gorau Best Light Entertainment DUDLEY - PRYD O SER DUDLEY NEWBERY / GARMON EMYR TUDUR OWEN O'R DOC ANGHARAD GARLICK / BETH ANGELL FFERM FACTOR NEVILLE HUGHES / NON GRIFFITH Y Rhaglen Gerddorol Orau Best Music Programme Noddir Gan/Sponsored By LLYR YN CARNEGIE HEFIN OWEN PAPA HAYDN RHIAN A. -

Edrych I'r Dyfodol Looking to the Future

S4C: Edrych i’r Dyfodol Looking to the Future Cyflwyniad Introduction Darlledwr gwasanaeth cyhoeddus yw S4C, sy’n S4C is a public service broadcaster, offering the cynnig yr unig wasanaeth teledu Cymraeg yn y world’s only Welsh-language television service. byd. Mae cyfraniad y sianel i fywydau, diwylliant The channel’s contribution to people’s lives, ac economi’r Gymru fodern yn bellgyrhaeddol. culture and the economy in modern Wales is Mae iddi le unigryw yn yr hinsawdd ddarlledu ac far-reaching. It occupies a unique space in the mae’n chwarae rhan bwysig o ran amrywiaeth broadcasting ecology, and plays an important llais a chynnwys o fewn y cyfryngau yng role in ensuring a diversity of voices and content Nghymru a’r Deyrnas Unedig. in the media in Wales and the United Kingdom. Mae’r diwydiant darlledu yn newid yn gyflym The broadcasting industry is changing rapidly, ond mae’r profiad o wylio, ar sgrin fawr neu sgrin but the experience of viewing, be it on a large or fach, gartref neu ar daith, yn dal i chwarae rhan small screen, at home or on the move, still plays ganolog ym mywydau’r mwyafrif llethol o bobl. a central role in the lives of the vast majority of people. Wrth i ddulliau gwylio ac ymateb amlhau, rhaid sicrhau fod y Gymraeg, ac S4C, yn gallu gwneud As means of viewing and interacting proliferate, yn fawr o’r cyfleoedd sydd ar gael i ddod â there is a need to ensure that the Welsh chymunedau at ei gilydd mewn ffyrdd newydd. -

Role Models, English E-Use

Role Models Being lesbian, gay, bi and trans in Wales Role Models Being lesbian, gay, bi and trans in Wales Stonewall Cymru Transport House Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9SB 08000 50 20 20 www.stonewall.cymru Written and produced by Ffion Grundy, Iestyn Wyn, Shon Faye, Joe Rossiter, Philippe Demougin Photos by Sioned Birchall at Camera Sioned Design by www.createpod.com Contents Introduction p.5 Role Models Numair Masud p.6 Delyth Liddell p.18 Bioscience Researcher Methodist Minister, Coordinating Chaplain at Cardiff University Caroline Bovey p.8 Dietician Marc Rees p.20 Artist Phil Forder p.10 Prison Manager Selena Caemawr p.22 Activist, Entrepreneur Samantha Carpenter p.12 and Writer Semi-Retired Sarah Lynn p.24 Megan Pascoe p.14 Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Project Manager Business Engagement Manager Elgan Rhys p.16 Writer-Director-Performer The importance and impact of role models p.26 STONEWALL CYMRU ROLE MODELS page 5 Furthermore, this year, the acute discrimination black people face has been brought to the forefront, with Introduction black LGBT people being severely affected by the global pandemic, as well as the trauma of systemic racism, homophobia, biphobia and transphobia experienced by Iestyn Wyn, the entire community. Now more than ever is a time for Campaigns, Policy and LGBT people and allies to come together to support those who need it. Role models can play an important role as Research Manager, valuable support systems for their peers. The role models assembled in this guide display a variety Stonewall Cymru of experiences and intersectional identities. It is vital that we do all we can to provide representation for a range of different identities. -

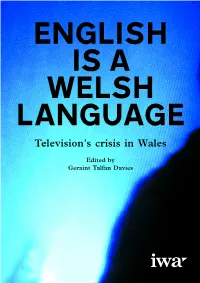

English Is a Welsh Language

ENGLISH IS A WELSH LANGUAGE Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies Published in Wales by the Institute of Welsh Affairs. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means without the prior permission of the publishers. © Institute of Welsh Affairs, 2009 ISBN: 978 1 904773 42 9 English is a Welsh language Television’s crisis in Wales Edited by Geraint Talfan Davies The Institute of Welsh Affairs exists to promote quality research and informed debate affecting the cultural, social, political and economic well-being of Wales. IWA is an independent organisation owing no allegiance to any political or economic interest group. Our only interest is in seeing Wales flourish as a country in which to work and live. We are funded by a range of organisations and individuals. For more information about the Institute, its publications, and how to join, either as an individual or corporate supporter, contact: IWA - Institute of Welsh Affairs 4 Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9LJ tel 029 2066 0820 fax 029 2023 3741 email [email protected] web www.iwa.org.uk Contents 1 Preface 4 1/ English is a Welsh language, Geraint Talfan Davies 22 2/ Inventing Wales, Patrick Hannan 30 3/ The long goodbye, Kevin Williams 36 4/ Normal service, Dai Smith 44 5/ Small screen, big screen, Peter Edwards 50 6/ The drama of belonging, Catrin Clarke 54 7/ Convergent realities, John Geraint 62 8/ Standing up among the cogwheels, Colin Thomas 68 9/ Once upon a time, Trevor -

Bangor University DOETHUR MEWN ATHRONIAETH Tri Dramodydd Cyfoes Meic Povey, Siôn Eirian Ac Aled Jones Williams Williams, Manon

Bangor University DOETHUR MEWN ATHRONIAETH Tri dramodydd cyfoes Meic Povey, Siôn Eirian ac Aled jones Williams Williams, Manon Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Prifysgol Bangor Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Tri Dramodydd Cyfoes: Meic Povey, Siôn Eirian ac Aled Jones Williams Traethawd Ph.D. Manon Wyn Williams Ysgol y Gymraeg Prifysgol Bangor Hydref 2015 Datganiad a Chaniatâd Manylion y Gwaith Rwyf trwy hyn yn cytuno i osod yr eitem ganlynol yn y gadwrfa ddigidol a gynhelir gan Brifysgol Bangor ac/neu mewn unrhyw gadwrfa arall yr awdurdodir ei defnyddio gan Brifysgol Bangor. Enw’r Awdur: Manon Wyn Williams Teitl: Tri Dramodydd Cyfoes: Meic Povey, Siôn Eirian ac Aled Jones Williams Goruchwyliwr/Adran: Yr Athro Gerwyn Wiliams, Ysgol y Gymraeg Corff cyllido (os oes): Y Coleg Cymraeg Cenedlaethol Cymhwyster/gradd a enillwyd: ………………………………………………………………………. -

Angela Graham Writer, Producer, Director

Résumé Angela Graham Writer, Producer, Director M.A. Oxford University, English Language and Literature with Latin P.G.C.E. (Distinction) Queen’s University, Belfast PRODUCER DNA Cymru S4C 5 x 60 Genetics/History Merthyr Meirionnydd S4C 1 x 60 Martyrdom One And All ITV Network 5 x 30 Self and Society. Plant Mari BBC /S4C 1 x 60 C 1 60 Catholicism in Wales The Cross Channel 4 1 x 60 ‘Banned’ Season Y Byd Ar Bedwar S4C 1 x 30 Anglo-Irish Agreement Say Yer Alphabet, Wee Doll HTV 1 x 30 Autobiography Living Proof 2 Series HTV 12 x 30 Relationships Birth Matters HTV 5 x 30 Maternity Services DEVELOPMENT PRODUCER The Story of Wales BBC 2, BBC Wales 6 x 60 Welsh History PRODUCER, SPECIALIST CONTENT The Story of Wales on the Hwb iTunesU 40 x 8 Welsh History Creu Cymru Fodern S4C 3 x 60 Welsh History EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Begin With The Heart Columba DVD 1 x 120 FEATURE FILM PRODUCER BRANWEN S4C 98 minutes SCREENWRITER Branwen S4C co-writer Plentyn Siawns S4C 90 minutes Mercy Teliesyn 30 minutes Mortal Beauty / Bellezza Mortale Green Bay Media 90 minutes RESEARCHER Alternatives ITV Network 6 x 30 The Divided Kingdom Channel 4 4 x 60 7 Series Health, Education, Architecture, Farming HTV 35 x 30 Ageless Ageing ITV Network 6 x 30 Various Schools series HTV/S4C 30 programmes PRESENTER Plant Mari S4C 1 x 60 Y Byd Ar Bedwar S4C 1 x 30 Say Yer Alphabet, Wee Doll HTV 1 x 30 Of Mourning and Memory BBC Radio Wales 1 x 30 2014 Weekend Word BBC Radio Wales 2010 - Pause For Thought BBC Radio 2 2011 - Prayer for the Day BBC Radio 4 2015 UNIVERSITY TEACHER Professional -

British Academy Cymru Awards

British Academy Cymru Awards Rules and Guidelines 2021 1 British Academy of Film & Television Arts Wales British Academy Cymru Awards Rules and Guidelines 2021 CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION AND TIMETABLE ............................................................................................................... 3 B. ELIGIBILITY AND CANDIDATE FOR NOMINATION ................................................................................... 4 ENTRY, SUPPORTING MATERIAL & ENTRY FEES ................................................................................................. 7 C. DIVERSITY AND SUSTAINABILITY ................................................................................................................. 9 D. BAFTA AWARDS ENTRY VIDEO UPLOAD TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS ............................................ 10 E. AWARD CATEGORIES ............................................................................................................................... 11 1. SPECIAL AWARD: SIAN PHILLIPS AWARD .......................................................................................... 11 2. SPECIAL AWARD: OUTSTANDING CONTRIBUTION ........................................................................... 11 3. FEATURE / TELEVISION FILM ................................................................................................................. 11 4. TELEVISION DRAMA .............................................................................................................................. 11 5. NEWS AND CURRENT -

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee S4C Fifth Report of Session 2010–12 Volume 1: Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/welshcom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 27 April 2011 HC 614 Published on 11 May 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £20.00 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales). Current membership David T.C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) (Chair) Stuart Andrew MP (Conservative, Pudsey) Guto Bebb MP (Conservative, Aberconwy) Alun Cairns MP (Conservative, Vale of Glamorgan), Geraint Davies MP (Labour, Swansea West) Jonathan Edwards MP (Plaid Cymru, Carmarthen East and Dinefwr) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Susan Elan Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Karen Lumley MP (Conservative, Redditch) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Owen Smith MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Mr Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) The following Members were members of the committee during the Parliament: Glyn Davies MP (Conservative, Montgomeryshire) Nia Griffith MP (Labour, Llanelli) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC.