The Mystery of Mary Stuart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form in Sixteenth-Century Scottish Inventories: the Worst Sort of Bed Michael Pearce

Beds of ‘Chapel’ Form in Sixteenth-Century Scottish Inventories: The Worst Sort of Bed michael pearce 1 Lit parement: a ‘sperver’ with a corona over a bed without a tester or celour. Bibliothèque de Genève, MS Fr. 165 fol. 4, Charles VI and Pierre Salmon, c.1415 Several sixteenth-century Scottish inventories mention ‘chapel beds’. A chapel bed was constructed at Dunfermline palace in November 1600 for Anne of Denmark prior to the birth of Charles I. This article proposes that these were beds provided with a sus - pended canopy with curtains which would surround any celour or tester (Figure 1). The ‘chapel’ was perhaps equivalent with the English ‘sperver’ or ‘sparver,’ a term not much used in Scotland in the sixteenth century, and more commonly found in older English texts of the late Middle Ages. The curtains of the medieval sperver hung from a rigid former, which could be hoop-like, a roundabout or corona, suspended from the chamber ceiling and perhaps principally constructed around a wooden cross like a simple chandelier.1 This canopy with its two curtains drawn back was given the name sperver from a fancied resemblance to a type of hawk, while also bearing a strong resemblance to a bell tent. A form of the word used in Scotland in 1474 — sparwart — is close to the etymological root of the word for hawk.2 The rigid former was called 1 Leland (1770), pp. 301–02. 2 Treasurer’s Accounts, vol. 1 (1877), p. 141; Eames (1977), pp. 75 and 83; see Oxford English Dictionary, ‘Sparver’ and ‘Sperver’. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

Mary Queen of Scots a Narravtive and Defence

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS THE ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS : JOHN THOMSOtf AND J. F. THOMSON, M.A. M a\ V e.>r , r\ I QUEEN OF SCOTS A NARRATIVE AND DEFENCE WITH PORTRAIT AND EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS SPECIALLY DRAWN FOR THE WORK ABERDEEN THE UNIVERSITY PRESS I 889r 3,' TO THE MEMORY OF MARY MARTYR QUEEN OF SCOTS THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE ebtcdfeb A PURE WOMAN, A FAITHFUL WIFE, A SOVEREIGN ENLIGHTENED BEYOND THE TUTORS OF HER AGE FOREWORD. effort is made in the few following AN pages to condense the reading of many years, and the conclusion drawn from almost all that has been written in defence and in defame of Mary Stuart. Long ago the world was at one as to the character of the Casket Letters. To these forgeries the writer thinks there must now be added that document discovered in the Charter Room of Dunrobin Castle by Dr. John Stuart. In that most important and deeply interesting find, recently made in a loft above the princely stables of Belvoir Castle, in a letter from Randolph to Rutland, of loth June, 1563, these words occur in writing about our Queen : "She is the fynneste she that ever was ". This deliberately expressed opinion of Thomas Randolph will, I hope, be the opinion of my readers. viii Foreword. The Author has neither loaded his page with long footnote extracts, nor enlarged his volume with ponderous glossarial or other appendices. To the pencil of Mr. J. G. Murray of Aber- deen, and the etching needle of M. Vaucanu of Paris, the little book is much beholden. -

Seton Collegiate Church

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC160 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13368) Taken into State care: 1948 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2015 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SETON COLLEGIATE CHURCH We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT -

The 5Th Earl of Argyll and Mary, Queen of Scots

THE FIFTH EARL OF ARGYLL AND MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS When Mary, Queen of Scots' name is linked to that of a man most people think immediately of high romance and passion, or even murder and rape, with a large dollop of tragedy thrown in. Three husbands had come and gone by the time Mary was twenty-five and during her long dreary single years in an English prison there was still continuous intrigue and speculation about a fourth. But the tragedy and Victorian-style melodrama of her marriages to Francis II, who died as a teenager in 1560, Darnley, who was murdered in 1567, and Bothwell, who fled Scotland in 1568, went mad in a Danish prison and died in 1578, have overshadowed the less-highly charged relationships she had with the Scottish nobles of her court. One of the most important of these was the affectionate friendship with her brother- in-law, the fifth earl of Argyll. Archibald Campbell, the 5th earl was not much older than Mary herself. He was probably born in 1538 so would have been only four years old in the dramatic year of 1542. It witnessed the birth of Mary on 8 December and, within a week, the death of her father, James V [1513-42], which made her ruler of Scotland. A regency was established with Mary as titular queen, but the main struggle for power was between those Scots who favoured the alliance with France and those who wanted friendship with England. The key issue was whether the young Queen would marry a French or an English prince. -

Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Triumphs of Petrarke and Its Castalian Circles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, commendatory verse and Jacobean poetics: William Fowler's triumphs of Petrarke and its Castalian circles. In: Parkinson, D.J. (ed.) James VI and I, Literature and Scotland: Tides of Change, 1567-1625. Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 45- 63. ISBN 9789042926912 Copyright © 2013 Peeters Publishers A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/69695/ Deposited on: 23 September 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk James VI and I, Literature and Scotland Tides of Change, 1567-1625 EDITED BY David J. Parkinson PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA 2013 CONTENTS Plates vii Abbreviations vii Note on Orthography, Dates and Currency vii Preface and Acknowledgements ix Introduction David J. Parkinson xi Contributors xv Shifts and Continuities in the Scottish Royal Court, 1580-1603 Amy L. Juhala 1 Italian Influences at the Court of James VI: The Case of William Fowler Alessandra Petrina 27 Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Trivmphs of Petrarke and its Castalian Circles Theo van Heijnsbergen 45 The Maitland -

The Silver Bough a Four Volume Study of the National and Local Festivals of Scotland

THE SILVER BOUGH A FOUR VOLUME STUDY OF THE NATIONAL AND LOCAL FESTIVALS OF SCOTLAND F. MARIAN McNEILL VOLUME FOUR THE LOCAL FESTIVALS OF SCOTLAND Contents Publisher’s Note Foreword Introduction 1: Festivals of Spring 2. Festivals of Summer and Autumn 3. Festivals of Winter 4. Highland Gatherings 5. Some lapsed festivals Acknowledgements Notes Illustrations PUBLISHER’S NOTE THE AUTHOR F. Marian McNeill was born in 1885 at Holm in Orkney where her father was the minister of the Free Presbyterian Kirk and it was this early life on the islands which would shape her life-long passion for Scottish culture and history. She moved from Orkney so that her secondary education could be continued in Glasgow and then Paris and the Rhineland. She travelled extensively as a young woman, visiting Greece, Palestine and Egypt and then living and working in London as part of the suffragette movement. Her first book Iona: A History of the Island was published in 1920 following her visit to the island. Her only novel, The Road Home, was published in 1932 and was loosely based on her years in Glasgow and London. The Scottish traditions which Marian had been brought up on shaped two of her books, The Scots Kitchen (published in 1929) and The Scots Cellar (1956), which both celebrated old recipes and customs and provide a social history of northern domestic life. Marian MacNeill was most proud, however, of this, her four-volume work, The Silver Bough (1957–1968), a study of Scottish folklore and folk belief as well as seasonal and local festivals. -

Irish and Scots

Irish and Scots. p.1-3: Irish in England. p.3: Scottish Regents and Rulers. p.4: Mary Queen of Scots. p.9: King James VI. p.11: Scots in England. p.14: Ambassadors to Scotland. p.18-23: Ambassadors from Scotland. Irish in England. Including some English officials visiting from Ireland. See ‘Prominent Elizabethans’ for Lord Deputies, Lord Lientenants, Earls of Desmond, Kildare, Ormond, Thomond, Tyrone, Lord Bourke. 1559 Bishop of Leighlin: June 23,24: at court. 1561 Shane O’Neill, leader of rebels: Aug 20: to be drawn to come to England. 1562 Shane O’Neill: New Year: arrived, escorted by Earl of Kildare; Jan 6: at court to make submission; Jan 7: described; received £1000; Feb 14: ran at the ring; March 14: asks Queen to choose him a wife; April 2: Queen’s gift of apparel; April 30: to give three pledges or hostages; May 5: Proclamation in his favour; May 26: returned to Ireland; Nov 15: insulted by the gift of apparel; has taken up arms. 1562 end: Christopher Nugent, 3rd Lord Delvin: Irish Primer for the Queen. 1563 Sir Thomas Cusack, former Lord Chancellor of Ireland: Oct 15. 1564 Sir Thomas Wroth: Dec 6: recalled by Queen. 1565 Donald McCarty More: Feb 8: summoned to England; June 24: created Earl of Clancare, and son Teig made Baron Valentia. 1565 Owen O’Sullivan: Feb 8: summoned to England: June 24: knighted. 1565 Dean of Armagh: Aug 23: sent by Shane O’Neill to the Queen. 1567 Francis Agard: July 1: at court with news of Shane O’Neill’s death. -

Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Men of Fife of Past and Present Times

FIFESHIKE BIOGRAPHY. WAL Terror bomb ; and in June following assumed the temporary command of the W Trusty, 50. In this vessel he was sent to convey five East Indiamen to a latitude in WAID, Andrew, Lieutenant in the which they might be safely left ; which Eoyal Navy, a native of Anstruther, died having done, he heard on his return of a near London in the year 1804. Having no large fleet of merchantmen which had been issue, he exetuted a trust disposition and for some time lying at Cadiz in want of settlement on the 4th December 1800. by convoy, and under heavy demurrage. Con- which he disponed and conveyed his whole ceiving he could not be more beneficially property, heritable and moveable, real and employed than in protecting the commerce personal, after paying annuitie.s of £203 15s of his country, Captain Walker thought fit to various persons whom he named, and {in contravention of his orders, which were others whom he substituted in their room to return to Spitliead), to take charge of after his death, to twelve trustees for the these vessels, which he conducted in perfect (lurpose of erecting; an academy at An- safety to England. Two memorials of the struther, his birth-place, for the reception, Spanish merchants residing in London accommodation, clothing, and education, as represented to the Admiralty "that the well as maintenance of as many orphan value of the fleet amounted to upwards of a boys and seamen's boys, in indigent million sterling, which but for his active circumstances, giving the preference to exertions would have been left in great orphans, as the whole of his estate would danger, at a most critical time, when the admit of, and appointed the erection of the Spaniards were negotiating a peace with said academy to be set about as soon as France." The Spanish authorities, how- £100 sterling of the foresaid annuities should ever, having resented his having assisted the cease. -

Mary, Queen of Scots in Popular Culture

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Mary, Queen of Scots in Popular Culture Diplomová práce Bc. Gabriela Taláková Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 28. 4. 2016 ..................................... Poděkování Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Emě Jelínkové, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k diplomové práci, a také za její vstřícnost a čas. Content Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Two Queens in One Isle ............................................................................................ 4 2. A Child Queen of Scotland ....................................................................................... 8 2.1 Historical Biographies ..................................................................................... 8 2.2 Fiction ............................................................................................................ 12 3. France ....................................................................................................................... 15 3.1 Mary and the Dauphin: A Marriage of Convenience? ................................... 15 3.1.1 Historical Biographies ....................................................................... 15 3.1.2 Fiction -

Printing Discovered and Intercepted Letters in England, 1571–1600

Propaganda, Patriotism, and News: Printing Discovered and Intercepted Letters In England, 1571–1600 GARY SCHNEIDER University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley Abstract: In this article I propose that the relatively few intercepted and discovered letters printed during the reign of Elizabeth I fall chiefly into three categories: they were published as propaganda, as patriotic statement, and as news reportage. Although Elizabeth and her ministers published intercepted and discovered letters on a strictly ad hoc and contingent basis, the pamphlets and books in which these letters appear, along with associated ideo- logical and polemical material, reveals determined uses of intercepted and discovered let- ters in print. Catholics likewise printed intercepted letters as propaganda to confront Eliz- abeth’s anti-Catholic policies through their own propaganda apparatus on the continent. Intercepted letters were also printed less frequently to encourage religious and state patri- otism, while other intercepted letters were printed solely as new reportage with no overt ideological intent. Because intercepted and discovered letters, as bearers of secret infor- mation, were understood to reveal sincere intention and genuine motivation, all of the pub- lications assessed here demonstrate that such letters not only could be used as effective tools to shape cultural perceptions, but could also be cast as persuasive written testimony, as legal proof and as documentary authentication. he years of the English civil wars are the ones usually associated with -

The Fringes of Fife

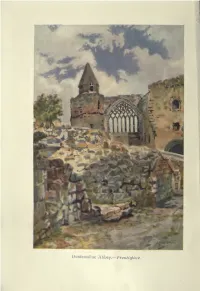

Uuniermline Ahh^y.—Frojitisptece. THE FRINGES OF FIFE NEW AND ENLARGED EDITION BY JOHN GEDDIE Author ot "The FiiniJes of Edinburjh," etc. Illustrated by Artliur Wall and Louis Weirter, R.B.A. LONDON: 38 Soto Square. W. 1 W. & R. CHAMBERS. LIMITED EDINBURGH: 339 High Street TO GEORGE A WATERS ' o{ the ' Scotsman MY GOOD COLLEAGUE DURING A QUARIER OF A CENTURY FOREWORD *I'll to ¥\ie:—Macl'eth. Much has happened since, in light mood and in light marching order, these walks along the sea- margin of Fife were first taken, some three-and-thirty years ago. The coasts of 'the Kingdom' present a surface hardened and compacted by time and weather —a kind of chequer-board of the ancient and the modern—of the work of nature and of man ; and it yields slowly to the hand of change. But here also old pieces have fallen out of the pattern and have been replaced by new pieces. Fife is not in all respects the Fife it was when, more than three decades ago, and with the towers of St Andrews beckoning us forward, we turned our backs upon it with a promise, implied if not expressed, and until now unfulfilled, to return and complete what had been begun. In the interval, the ways and methods of loco- motion have been revolutionised, and with them men's ideas and practice concerning travel and its objects. Pedestrianism is far on the way to go out of fashion. In 1894 the 'push-bike' was a compara- tively new invention ; it was not even known by the it was still name ; had ceased to be a velocipede, but a bicycle.