NGA: Guide to the Exhibition the Sacred Made Real

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Age by Gema De La Torre Is Licensed Under a Unit 8 – the Baroque Age Creative Commons Reconocimiento-Nocomercial 4.0 Internacional License

The Baroque Age by Gema de la Torre is licensed under a Unit 8 – The Baroque Age Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional License Unit 8 – The Baroque age Index 1. Society ................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Political Systems ................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Absolutism ..................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2. The Parliamentary Systems ........................................................................................................... 4 3. International Relations .......................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) ............................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Franco-Spanish War (1648-59) ............................................................................................... 5 4. The Scientific Revolution .................................................................................................................... 5 4.1. New Philosophical Movements. .................................................................................................... 6 Empiricism...................................................................................................................................... -

Spanish Master Drawings from Cano to Picasso

Spanish Master Drawings From Cano to Picasso Spanish Master Drawings From Cano to Picasso When we first ventured into the world of early drawing at the start of the 90s, little did we imagine that it would bring us so much satisfaction or that we would get so far. Then we organised a series of five shows which, with the title Raíz del Arte (Root of Art), brought together essentially Spanish and Italian drawing from the 16th to 19th centuries, a project supervised by Bonaventura Bassegoda. Years later, along with José Antonio Urbina and Enrique Calderón, our friends from the Caylus gallery, we went up a step on our professional path with the show El papel del dibujo en España (The Role of Drawing in Spain), housed in Madrid and Barcelona and coordinated by Benito Navarrete. This show was what opened up our path abroad via the best possible gate- way, the Salon du Dessin in Paris, the best drawing fair in the world. We exhibited for the first time in 2009 and have kept up the annual appointment with our best works. Thanks to this event, we have met the best specialists in drawing, our col- leagues, and important collectors and museums. At the end of this catalogue, you will find a selection of the ten best drawings that testify to this work, Spanish and Italian works, but also Nordic and French, as a modest tribute to our host country. I would like to thank Chairmen Hervé Aaron and Louis de Bayser for believing in us and also the General Coordinator Hélène Mouradian. -

Ribera's Drunken Silenusand Saint Jerome

99 NAPLES IN FLESH AND BONES: RIBERA’S DRUNKEN SILENUS AND SAINT JEROME Edward Payne Abstract Jusepe de Ribera did not begin to sign his paintings consistently until 1626, the year in which he executed two monumental works: the Drunken Silenus and Saint Jerome and the Angel of Judgement (Museo di Capodimonte, Naples). Both paintings include elaborate Latin inscriptions stating that they were executed in Naples, the city in which the artist had resided for the past decade and where he ultimately remained for the rest of his life. Taking each in turn, this essay explores the nature and implications of these inscriptions, and offers new interpretations of the paintings. I argue that these complex representations of mythological and religious subjects – that were destined, respectively, for a private collection and a Neapolitan church – may be read as incarnations of the city of Naples. Naming the paintings’ place of production and the artist’s city of residence in the signature formulae was thus not coincidental or marginal, but rather indicative of Ribera inscribing himself textually, pictorially and corporeally in the fabric of the city. Keywords: allegory, inscription, Naples, realism, Jusepe de Ribera, Saint Jerome, satire, senses, Silenus Full text: http://openartsjournal.org/issue-6/article-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2018w05 Biographical note Edward Payne is Head Curator of Spanish Art at The Auckland Project and an Honorary Fellow at Durham University. He previously served as the inaugural Meadows/Mellon/Prado Curatorial Fellow at the Meadows Museum (2014–16) and as the Moore Curatorial Fellow in Drawings and Prints at the Morgan Library & Museum (2012–14). -

Nueva Información Sobre Alonso Cano

AEA, LXXVII, 2004, 305, pp. 75 a 97. ISSN: 0004-0428 VARIA NUEVA INFORMACIÓN SOBRE ALONSO CANO Como aportación documental al cuarto centenario del nacimiento del pintor, escultor y arqui tecto granadino Alonso Cano (1601-1667) presentamos una nueva noticia que esperamos ayude en futuras investigaciones a precisar aún más sobre la vida y obra de tan destacado genio '. En contadas ocasiones hallamos testimonio escrito donde se efectúa un contrato artístico para una clientela particular al margen de los habituales encargos eclesiásticos o reales en tor no a los pintores españoles del siglo xvii ^. El 28 de mayo de 1660 Cano concierta en Madrid la elaboración de una nueva obra dentro de su producción pictórica I Licenciado, Racionero de la Santa Iglesia de Granada y Procurador Fiscal de la Cámara Apostólica de esta ciudad, se omite a priori junto a estos oficios su profesión por la pintura. El encargo se efectúa por orden de Blas López, un maestro del arte de escribir del que hasta el momento carecemos de más información. Mediante convenio se especifica que Alonso Cano «le halla de hacer de pintura un cuadro con dos figuras, la una de Nuestro Señor tendido en el regazo de Nuestra Señora, que a de ser la otra figura» con unas medidas de «dos varas y media de ancho y dos varas de alto». La obra será entregada en «octubre que viene de este presente año» y su coste será de mil reales de vellón haciéndose el pago mediante «diferentes alhajas y estampas». Tras el pro tocolo habitual en este tipo de contratos aparecen como testigos Tomás de Almansa y la Plaza, Juan Ruiz y Juan Alvarez '^. -

Century Seville Painting

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Volume 66, issue 4 – 2018 SELECTED PAPERS IN ENGLISH DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/rh.2018.66.4-6e FR. ANDRZEJ WITKO * STILL LIFE IN 17TH-CENTURY SEVILLE PAINTING Still life representations showing various man-made objects such as dishes, weapons, books, candles, kitchen utensils, musical instruments, cards, but also food items such as fruit, vegetables, bread, sweets, eggs, fish and animals, as well as flowers and human skulls, are referred to in Spanish as the bodegón.1 Originally, the term had a much broader meaning and in- cluded so-called kitchen scenes, which were of particular interest to young Diego Velázquez, today considered a part of genre painting. Man-made ob- jects were rarely the main theme of Spanish bodegones. If they appeared, they usually accompanied other natural products. Although this genre of painting never developed especially in Seville, it did enjoy a certain popular- ity there. This was due to both typical aesthetic feelings and the experience of Black Death. The resulting hunger, lack of food and meagre harvests pro- voked the creation of unusually “appetizing” still lifes, which were supposed to compensate for the acute food shortages. The plague and the spreading death toll moreover inspired the creation of superb still lifes that emphasized the futility of human life. There were also still lifes referring to specific litur- gical periods, e.g. Christmas or Lent, particular seasons and months, taking Fr. Prof. Dr Hab. ANDRZEJ WITKO – head of the Department of Modern Art History, Institute of Art and Culture History, John Paul II Pontifical University in Krakow; address for correspon- dence: ul. -

The Immaculate Conception C

[5] granada school, second half of the 17th century The Immaculate Conception c. 1650-1680 Black chalk, pen and black ink and white wash on paper 360 x 235 mm he frequent depiction of the Immaculate Conception rosy cheeks, her beautiful hair spread out and the colour of in 17th -century Spain can be seen as a responding gold [...]. She must be painted wearing a white tunic and to a desire to defend the cult of the Virgin and her blue mantle [and be] crowned with stars; twelve stars forming T 1 virginity against Protestant doubts. Stylistically, depictions a bright circle between glowing light, with her holy brow as of this subject evolved in parallel to the general evolution of the central point.” 2 17 th -century art. Thus, in the fi rst third of the century such Cano’s Immaculate Conceptions evolved in parallel to images were characterised by a restrained, tranquil mood with his work as a whole but always remained faithful to Pacheco’s the Virgin presented as a static, frontal fi gure. In the second precepts. They range from his most static depictions of the third of the century, however, a new approach showed her as early 1620s, such as the one in a private French collection, 3 advancing forward majestically with a suggestion of upward to those from the end of his career, which convey the greatest movement in the draperies. Finally, in the last third of the sense of movement, including the ones painted for the century the fi gure of Mary soared upwards, enveloped in cathedrals in Granada (c. -

Winter Dialogue-Final-2

Docent Council Dialogue Winter 2013 Published by the Docent Council Volume XLIIl No 2 From Ethereal to Earthy The Legacy of Caravaggio 1 Inside the Dialogue Reflections on a Snowy Morning.......................Diane Macris, President, Docent Council Page 3 Winter Message..................................................Charlene Shang Miller, Docent and Tour Programs Manager Page 3 A Docent’s Appreciation of Alona Wilson........................................................JoAn Hagan, Docent Page 4 An Idea whose Time had Come................................Sandy Voice Page 5 Presentations:Works of Art from Burst of Light ......Docent Contributors Pages 7-20 The Transformative Genius of Caravaggio...............JoAn Hagan Page10 Flicks: The Dialogue Goes to the Cinema....................................................Sandy Voice Page 10 A Docent’s Guide to the Saints..................................Beth Malley Page 11 From the Sublime to the Ridiculous and Back..........Hope Vath Page 13 The Bookshelf: A Book Review.................................BethMalley Page 15 A Passion for Stickley ...............................................Laura Harris Page 20 From the Collection of Stephen Gray Docent Council Dialogue The Dialogue is created by and for docents and provides a forum for touring ideas and techniques, publishing information that is vital to docent interests such as museum changes, and recording docent activities and events. The newsletter is published in Fall, Winter, and Spring editions. Editorial Staff Sandy Voice Co-Editor -

José De Mora SAINT ANTHONY of PADUA

José de Mora Baza, 1642 – Granada, 1724 SAINT ANTHONY OF PADUA José de Mora Baza, 1642 – Granada, 1724 Saint Anthony of Padua Ca 1700-1720 Polychrome wood Saint: 40.5; plinth: 15; whole: 55.5 cm Saint Anthony: height 56.5 cm, plinth base width 22×22 cm, plinth height 16 cm Figure 40.5 cm Saint Anthony of Padua was actually of Portuguese descent, born to a noble family from Lisbon. When he was fifteen years old he became an Augustinian monk, changing into a Franciscan in 1221. As a preacher he traveled around Spain, northern Africa and Italy, where he even met Saint Francis. He taught theology in Bologna and later he toured France while exercising his pastoral ministry. He spent his final years in Padua, where he died in 1231. After the sixteenth century, his worship reaches an enormous dimension, and he becomes one of the most popular and beloved saints, his image being widely spread through many media. The work under study results from the miraculous scene that will have the greatest impact on the iconography of the Portuguese saint, the appearance of the Infant Jesus, which during the Early Modern Period will become his most common attribute and one of the classic representations. In addition, it is also very common for the Child to appear standing or sitting on an open or closed book. In fact, this latter iconographic element does not appear in the hagiographic account. It might stem from some other traditions in which the miracle is said to have occurred while the Saint was preaching about the Incarnation dogma, so the vision allegedly arose from his reading, with the Child descending in order to attest it. -

Mediterraneo in Chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer E Mattia Preti Da Malta a Roma Mostra a Cura Di Sandro Debono E Alessandro Cosma

Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma mostra a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma Roma, Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma - Palazzo Barberini 12 gennaio 2017 - 21 maggio 2017 COMUNICATO STAMPA Le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma presentano dal 12 gennaio a 21 maggio 2017 nella sede di Palazzo Barberini Mediterraneo in chiaroscuro. Ribera, Stomer e Mattia Preti da Malta a Roma, a cura di Sandro Debono e Alessandro Cosma. La mostra raccoglie alcuni capolavori della collezione del MUŻA – Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti (Heritage Malta) de La Valletta di Malta messi a confronto per la prima volta con celebri opere della collezione romana. La mostra è il primo traguardo di una serie di collaborazioni che le Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma hanno avviato con i più importanti musei internazionali per valorizzare le rispettive collezioni e promuoverne la conoscenza e lo studio. In particolare l’attuale periodo di chiusura del museo maltese, per la realizzazione del nuovo ed innovativo progetto MUŻA (Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Arti, Museo Nazionale delle Arti), ha permesso di avviare un fruttuoso scambio che ha portato a Roma le opere in mostra, mentre approderanno sull’isola altrettanti dipinti provenienti dalle Gallerie Nazionali in occasione di una grande esposizione nell’ambito delle iniziative relative a Malta, capitale europea della cultura nel 2018. In mostra diciotto dipinti riprendono l’intensa relazione storica e artistica intercorsa tra l’Italia e Malta a partire dal Seicento, quando prima Caravaggio e poi Mattia Preti si trasferirono sull’isola come cavalieri dell’ordine di San Giovanni (Caravaggio dal 1606 al 1608, Preti per lunghissimi periodi dal 1661 e vi morì nel 1699), favorendo la progressiva apertura di Malta allo stile e alle novità del Barocco romano. -

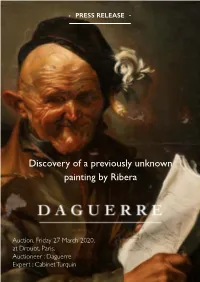

Discovery of a Previously Unknown Painting by Ribera

PRESS RELEASE Discovery of a previously unknown painting by Ribera Auction, Friday 27 March 2020, at Drouot, Paris. Auctioneer : Daguerre Expert : Cabinet Turquin Discovery of a previously unknown pain- ting by Ribera, a major 17th century artist Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) was only 20 years old when he painted this work, « The Mathematician ». The Spanish born artist was yet to achieve his renown as the great painter of Naples, the city considered to be one of the most important artistic centers of the 17th century. It is in Rome, before this Neapolitan period, in around 1610, that Ribera paints this sin- gular and striking allegory of Knowledge. The painting is unrecorded and was unknown to Ribera specialists. Now authenticated by Stéphane Pinta from the Cabinet Turquin, the work is to be sold at auction at Drouot on 27 March 2020 by the auction house Daguerre with an estimate of 200,000 to 300,000 Euros. 4 key facts to understand the painting 1. This discovery sheds new light on the artist’s early period that today lies at the heart of research being done on his oeuvre. 2. The painting portrays one of the artist’s favorite models, one that he placed in six other works from his Roman period. 3. In this painting, Ribera gives us one of his most surprising and colorful figures; revealing a sense of humor that was quite original for the time. 4. His experimenting with light and his choosing of a coarse and unfortunate sort of character to represent a savant echo both the chiaroscuro and the provocative art of Caravaggio. -

Images of the Last Judgment in Seville

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2014 Images of the Last Judgment in Seville: Pacheco, Herrera el Viejo, and the Phenomenological Experience of Fear and Evil Juan José López University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation López, Juan José, "Images of the Last Judgment in Seville: Pacheco, Herrera el Viejo, and the Phenomenological Experience of Fear and Evil" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 412. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/412 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMAGES OF THE LAST JUDGMENT IN SEVILLE: PACHECO, HERRERA EL VIEJO, AND THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPERIENCE OF FEAR AND EVIL by Juan José López A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee May 2014 ABSTRACT IMAGES OF THE LAST JUDGMENT IN SEVILLE: PACHECO, HERRERA EL VIEJO, AND THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL EXPERIENCE OF FEAR AND EVIL by Juan J. López The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, 2014 Under the supervision of Professor Tanya J. Tiffany During the early stages of the seventeenth century in Seville, images of the Last Judgment participated in a long artistic tradition of inspiring fear about the impending apocalypse. This thesis focuses on two paintings of the Last Judgment, one by Francisco Pacheco for the church of St. -

Virgin and Child and Portraits Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra: the Creative Context

Virgin and Child and portraits Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra: the creative context Javier Portús This text is published under an international Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Creative Commons licence (BY-NC-ND), version 4.0. It may therefore be circulated, copied and reproduced (with no alteration to the contents), but for educational and research purposes only and always citing its author and provenance. It may not be used commercially. View the terms and conditions of this licence at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-ncnd/4.0/legalcode Using and copying images are prohibited unless expressly authorised by the owners of the photographs and/or copyright of the works. © of the texts: Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao Photography credits © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa Fundazioa-Fundación Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao: fig. 1 © Catedral de Málaga. Photography: Eduardo Nieto, 2005: fig. 5 © Convento de San José de las Carmelitas Descalzas de Antequera, Málaga. Photography: Antonio Rama, 2005: fig. 2 © Curia Eclesiástica de Granada. Photography: Carlos Madero López, 2005: fig. 4 © Museo Nacional del Prado, cat. 6588, deposited, Museo de Bellas Artes de Granada. Photography: Vicente del Amo, 1998: fig. 3 Text published in: B’05 : Buletina = Boletín = Bulletin. Bilbao : Bilboko Arte Eder Museoa = Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao = Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, no. 1, 2006, pp. 43-66. Sponsored by: irgin and Child and portraits, by Pedro Atanasio Bocanegra (1638-1689) [fig. 1] is a quality addition to the collection of Bilbao Fine Arts Museum that already offers a notable overview of Spanish Golden V Age paint ing, with splendid works by Ribera, Zurbarán and Murillo, among others.