Interview with Phyllis Schlafly # ISE-A-L-2011-001.01 Interview # 1: January 5, 2011 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

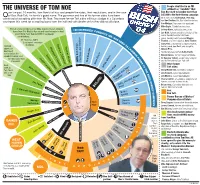

The Universe of Tom

People identified in an FBI THE UNIVERSE OF TOM NOE ■ affidavit as “conduits” that ver the past 10 months, Tom Noe’s fall has cost people their jobs, their reputations, and in the case Tom Noe used to launder more than Oof Gov. Bob Taft, his family’s good name. The governor and two of his former aides have been $45,000 to the Bush-Cheney campaign: convicted of accepting gifts from Mr. Noe. Two more former Taft aides will face a judge in a Columbus MTS executives Bart Kulish, Phil Swy, courtroom this week for accepting loans from the indicted coin dealer which they did not disclose. and Joe Restivo, Mr. Noe’s brother-in-law. Sue Metzger, Noe executive assistant. Mike Boyle, Toledo businessman. Five of seven members of the Ohio Supreme Court stepped FBI-IDENTIF Jeffrey Mann, Toledo businessman. down from The Blade’s Noe records case because he had IED ‘C OND Joe Kidd, former executive director of the given them more than $20,000 in campaign UIT S’ M Lucas County board of elections. contributions. R. N Lucas County Commissioner Maggie OE Mr. Noe was Judith U Thurber, and her husband, Sam Thurber. Lanzinger’s campaign SE Terrence O’Donnell D Sally Perz, a former Ohio representative, chairman. T Learned Thomas Moyer O her husband, Joe Perz, and daughter, Maureen O’Connor L about coin A U Allison Perz. deal about N D Toledo City Councilman Betty Shultz. a year before the E Evelyn Stratton R Donna Owens, former mayor of Toledo. scandal erupted; said F Judith Lanzinger U H. -

Cultural Anthropology Through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-Based Sentiment

Cultural Anthropology through the Lens of Wikipedia: Historical Leader Networks, Gender Bias, and News-based Sentiment Peter A. Gloor, Joao Marcos, Patrick M. de Boer, Hauke Fuehres, Wei Lo, Keiichi Nemoto [email protected] MIT Center for Collective Intelligence Abstract In this paper we study the differences in historical World View between Western and Eastern cultures, represented through the English, the Chinese, Japanese, and German Wikipedia. In particular, we analyze the historical networks of the World’s leaders since the beginning of written history, comparing them in the different Wikipedias and assessing cultural chauvinism. We also identify the most influential female leaders of all times in the English, German, Spanish, and Portuguese Wikipedia. As an additional lens into the soul of a culture we compare top terms, sentiment, emotionality, and complexity of the English, Portuguese, Spanish, and German Wikinews. 1 Introduction Over the last ten years the Web has become a mirror of the real world (Gloor et al. 2009). More recently, the Web has also begun to influence the real world: Societal events such as the Arab spring and the Chilean student unrest have drawn a large part of their impetus from the Internet and online social networks. In the meantime, Wikipedia has become one of the top ten Web sites1, occasionally beating daily newspapers in the actuality of most recent news. Be it the resignation of German national soccer team captain Philipp Lahm, or the downing of Malaysian Airlines flight 17 in the Ukraine by a guided missile, the corresponding Wikipedia page is updated as soon as the actual event happened (Becker 2012. -

Frontier Knowledge Basketball the Map to Ohio's High-Tech Future Must Be Carefully Drawn

Beacon Journal | 12/29/2003 | Fronti... Page 1 News | Sports | Business | Entertainment | Living | City Guide | Classifieds Shopping & Services Search Articles-last 7 days for Go Find a Job Back to Home > Beacon Journal > Wednesday, Dec 31, 2003 Find a Car Local & State Find a Home Medina Editorial Ohio Find an Apartment Portage Classifieds Ads Posted on Mon, Dec. 29, Stark 2003 Shop Nearby Summit Wayne Sports Baseball Frontier knowledge Basketball The map to Ohio's high-tech future must be carefully drawn. A report INVEST YOUR TIME Colleges WISELY Football questions directions in the Third Frontier Project High School Keep up with local business news and Business information, Market Arts & Living Although voters last month rejected floating bonds to expand the updates, and more! Health state's high-tech job development program, the Third Frontier Project Food The latest remains on track to spend more than $100 million a year over the Enjoy in business Your Home next decade. The money represents a crucial investment as Ohio news Religion weathers a painful economic transition. A new report wisely Premier emphasizes the existing money must be spent with clear and realistic Travel expectations and precise accountability. Entertainment Movies Music The report, by Cleveland-based Policy Matters Ohio, focuses only on Television the Third Frontier Action Fund, a small but long-running element of Theater the Third Frontier Project. The fund is expected to disburse $150 US & World Editorial million to companies, universities and non-profit research Voice of the People organizations. Columnists Obituaries It has been up and running since 1998, under the administration of Corrections George Voinovich. -

Was Ann Coulter Right? Some Realism About “Minimalism”

AMLR.V5I1.PRESSER.POSTPROOFLAYOUT.0511 9/16/2008 3:21:27 PM Copyright © 2007 Ave Maria Law Review WAS ANN COULTER RIGHT? SOME REALISM ABOUT “MINIMALISM” Stephen B. Presser † INTRODUCTION Ever since the Warren Court rewrote much of the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment, there has been a debate within legal academia about the legitimacy of this judicial law making.1 Very little popular attention was paid, at least in the last several decades, to this problem. More recently, however, the issue of the legitimacy of judicial law making has begun to enter the realm of partisan popular debate. This is due to the fact that Republicans controlled the White House for six years and a majority in the Senate for almost all of that time, that they have announced, as it were, a program of picking judges committed to adjudication rather than legislation, and finally, that the Democrats have, just as vigorously, resisted Republican efforts. Cass Sunstein, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School,2 and now a visiting professor at Harvard Law School,3 has written a provocative book purporting to be a popular, yet scholarly critique of the sort of judges President George W. Bush has announced that he would like to appoint. Is Sunstein’s effort an objective undertaking, or is it partisan politics with a thin academic veneer? If Sunstein’s work (and that of others on the Left in the † Raoul Berger Professor of Legal History, Northwestern University School of Law; Professor of Business Law, J. L. Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University; Legal Affairs Editor, Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture. -

Majority and Minority Leaders”, Available At

Majority and Minority Party Membership Other Resources Adapted from: “Majority and Minority Leaders”, www.senate.gov Available at: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Majority_Minority_Leaders.htm Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 3: Majority and Minority Whips (Assistant Floor Leaders) Chapter 4: Complete List of Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 5: Longest-Serving Party Leaders Introduction The positions of party floor leader are not included in the Constitution but developed gradually in the 20th century. The first floor leaders were formally designated in 1920 (Democrats) and 1925 (Republicans). The Senate Republican and Democratic floor leaders are elected by the members of their party in the Senate at the beginning of each Congress. Depending on which party is in power, one serves as majority leader and the other as minority leader. The leaders serve as spokespersons for their parties' positions on issues. The majority leader schedules the daily legislative program and fashions the unanimous consent agreements that govern the time for debate. The majority leader has the right to be called upon first if several senators are seeking recognition by the presiding officer, which enables him to offer motions or amendments before any other senator. Majority and Minority Leaders Elected at the beginning of each Congress by members of their respective party conferences to represent them on the Senate floor, the majority and minority leaders serve as spokesmen for their parties' positions on the issues. The majority leader has also come to speak for the Senate as an institution. Working with the committee chairs and ranking members, the majority leader schedules business on the floor by calling bills from the calendar and keeps members of his party advised about the daily legislative program. -

Conservative Women's Activism from Anticommunism to the New Christian Right

Hollins University Hollins Digital Commons Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Theses 2021 Mothers, Morals, and Godly Motivations: Conservative Women’s Activism from Anticommunism to the New Christian Right Kaitlyn C. Phillips Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/ughonors Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons MOTHERS, MORALS, AND GODLY MOTIVATIONS: CONSERVATIVE WOMEN’S ACTIVISM FROM ANTICOMMUNISM TO THE NEW CHRISTIAN RIGHT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts Department of History Hollins University May 2021 By Kaitlyn C. Phillips TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: 1 CHAPTER ONE: The Minute Women: Anticommunist Women, Domesticity and Conservative Unity 8 CHAPTER TWO: Phyllis Schlafly: The Privileged Status of Women and Idealized National Identity 20 CHAPTER THREE: Beverly LaHaye: The Evangelical Essentials and Women in the New Christian Right 35 CONCLUSION: 51 BIBLIOGRAPHY: 55 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To start, I want to thank Dr. Nunez for her guidance, care, and wisdom throughout this thesis process and my entire time at Hollins. Your kindness and sense of humor have brightened my days countless times, and when I think of myself as a potential scholar, I hope to be as thoughtful, knowledgeable, and passionate as you are. Additionally, I want to thank Dr. Florio and Dr. Coogan for their time, knowledge, and support. You have helped me in numerous ways and I am incredibly grateful for you both. I want to thank my father, Steven Phillips, for being just as big of a history nerd as I am. Lastly, I want to remember my grandfather Donald Bruaw, who showed me how to love history. -

The US Experiment with Government Ownership of the Telephone

University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law 4-1-2013 The Wires Go to War: The U.S. Experiment with Government Ownership of the Telephone System During World War I Michael A. Janson Federal Communications Commission Christopher S. Yoo University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Communications Law Commons, Economic History Commons, Legal History Commons, Other Business Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Science and Technology Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Janson, Michael A. and Yoo, Christopher S., "The Wires Go to War: The U.S. Experiment with Government Ownership of the Telephone System During World War I" (2013). Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law. 467. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/467 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship at Penn Law by an authorized administrator of Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles The Wires Go to War: The U.S. Experiment with Government Ownership of the Telephone System During World War I Michael A. Janson* & Christopher S. Yoo** One of the most distinctive characteristics of the U.S. telephone system is that it has always been privately owned, in stark contrast to the pattern of government ownership followed by virtually every other nation. What is not widely known is how close the United States came to falling in line with the rest of the world. -

College Faces $500,000 Budget Deficit

A Student UTER Publication Linn-Benlon Community College, Albany, ~on VOLUME 21 • NUMBER 7 Wednesday, Nov. 15, 1989 Winter term registration cards ready By Bev Thomas Of The Commuter Fully-admitted students who are cur- rently attending LHCC have first grab at classes during early registration for winter term providing they pick up an appoint- ment card, said LHCC Registar Sue Cripe. Appointment cards will be available at the registration counter Nov. 20 through Dec. 4. Registration counter hours are 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., Monday through Friday. Appointment registration days are as follows: students with last names H through 0, Tuesday, Dec. 5; last names P through Z, Wednesday, Dec. 6; last names A through G, Thursday, Dec. 7. Students who miss appointments, lose appointment cards or don't pick cards up may-still register early on Dec. 8, Dec. II or they may attend open registration beginning Dec. 12. Returning Evening Degree Program students may register from 7 to 8 p.m. On The COmmuler! JESS REF!; Dec. I, during open registration or by ap- pointment as a continuing fully-admitted Saluting Women Veterans student. Nursing student Carolyn Camden and Student Council Moderator Brian McMullen ride the ASLBCC float in Satur- Part-time student registration begins day's annual Albany Veterans Day Parade. Although the float was beaten out by one constructed by Calapooia Dec. 12 and Community Education Middle School for best in the parade, ASLBCC's entry did win recognition in its category. The LB float is an an. registration for credit and non-credit nual project constructed with the assistance of several campus clubs. -

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W

CBS NEWS 2020 M Street N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FACE THE NATION as broadcast over the CBS Television ~et*k and the -.. CBS Radio Network Sunday, August 6, 1967 -- 12:30-1:00 PM EDT NEWS CORREIS PONDENTS : Martin Agronsky CBS News Peter Lisagor Chicago Daily News John Bart CBS News DIRECTOR: Robert Vitarelli PRODUCEBS : Prentiss Childs and Sylvia Westerman CBS NEWS 2020 M Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEFSE HIGHLIGHTS FROM REMARKS OF HONORABLE EVERETT DIREEN, ,- U.S. SENATOR, REPUBLICAN OF ILLINOIS, ON "FACE THE NATI(3N" ON THE CBS TELEVISION AND THE CBS RADIO NETWORKS, SUNDAY, AUGUST 6, 1967 - 12:30-1:00 PM EST: -PAGE Riots and Urban problems Presented Republican Party statement blaming Pres. Johnson for riots, but would personally be cautious about allegations 1 and 13 In a good many communities there is evidence of outside in£luences triggering riots If conditions not ameliorated--will be "one of the monumental in '68" 3 issues -- - . -- - Congress has -not been "niggardly"--will kead figures to _Mayor Jerome Cavanagh before the Committee 8 Cincinnati police chief told Committee city was in good shape 9 Stokley Carmichael--treason is a sinister charge--must be proven 17 Vietnam Supports President ' s policy--he has most expert advice 4 and 5 7 Gun control bill Can better be handled at state level Would go along with moderate bill 4R. AGRONSKX: Senator Dirksen, a recent Republican Party ;tatement read by you blamed President Johnson for the racial riots. Your Republican colleague, Senator Thrus ton rIorton, denounced this as irresponsible. -

For State:Health Care

The Case for Impeachmet of- ichard Nixon., Part V Richard M. Nixon has com- such a way that we make major mitted an impeachable offense This article, sixth of a series, is reprinted fro&m the AFL-CIO impact on a basis which the net- by interfering with the constitu- News: the. official publication of the American Federation of Labor works, newspapers and Congress tionally guaranteed freedom of and Congress of Industrial Organizations, 815 Sixteenth Sttreet, will react to and begin to look at the press by means of wiretaps, NW,-. -W.ashington, DC. 20006. things somewhat differently. It T1I investigations and tireats is my opinion that we should be- d punitive action. requesting specific action relat- "It is my opinion this contin- gin concentrated efforts in a On Octeber 17, i9m, -former ing to what could be considered ual daily attempt to get to the number of major areas that will Yhite Rise aide Jeb Start unfair news coverage. In media or to anti-Administration have much more impact on the lagnir wt former FPtal- the short time that I have been spokesmen because of specific media and other anti-Adminis- enUtal Assat Ji. Halde- here, I would gather that there things they have said is very un- tration spokesmen and will do sian: have been at least double or fruitful and wasteful of our more good in the long run. The "I have enclosed from t-he log triple- this many requests made time. following is my suggestion as to approximately 21 requets from through- other parties to accom- "The real problem . -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty's Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism

Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Ash Center Occasional Papers Series Series Editor Tony Saich Deputy Editor Jessica Engelman The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion. By training the very best leaders, developing powerful new ideas, and disseminating innovative solutions and institutional reforms, the Center’s goal is to meet the profound challenges facing the world’s citizens. The Ford Foundation is a founding donor of the Center. Additional information about the Ash Center is available at ash.harvard.edu. This research paper is one in a series funded by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. The views expressed in the Ash Center Occasional Papers Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series are intended to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. This paper is copyrighted by the author(s). It cannot be reproduced or reused without permission. Ash Center Occasional Papers Tony Saich, Series Editor Something Has Cracked: Post-Truth Politics and Richard Rorty’s Postmodernist Bourgeois Liberalism Joshua Forstenzer University of Sheffield (UK) July 2018 Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation Harvard Kennedy School Letter from the Editor The Roy and Lila Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation advances excellence and innovation in governance and public policy through research, education, and public discussion.