THE VIOLIST AS COMPOSER Sarah Marie Hart, Doctor Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021.5.17 Chamber Fest 2 R3

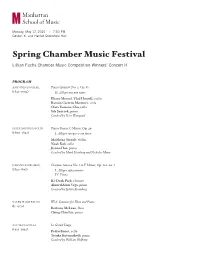

Monday, May 17, 2021 | 7:30 PM Gordon K. and Harriet Greenfield Hall Spring Chamber Music Festival Lillian Fuchs Chamber Music Competition Winners’ Concert II PROGRAM ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Piano Quintet No. 2, Op. 81 (1841–1904) II. Allegro ma non tanto Eliane Menzel, Vlad Hontilă, violin Ramón Carrero Martínez, viola Clara Yeonsue Cho, cello Sıla Şentürk, piano Coached by Peter Winograd FELIX MENDELSSOHN Piano Trio in C Minor, Op. 49 <Piano Trio No. 2 in C Minor, Op. 66?> (1809–1847) I. Allegro energico e con fuoco Maïthéna Girault, violin Noah Koh, cello Jiyoon Han, piano Coached by Mark Steinberg and Nicholas Mann JOHANNES BRAHMS Clarinet Sonata No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 120, no. 1 (1833–1897) I. Allegro appassionato IV. Vivace Ki-Deok Park, clarinet Ahmed Alom Vega, piano Coached by Sylvia Rosenberg VALERIE COLEMAN Wish: Sonatine for Flute and Piano (b. 1970) Bethany McLean, flute Ching Chia Lin, piano ASTOR PIAZOLLA Le Grand Tango (1921–1992) Pedro Bonet, cello Tatuka Kutsnashvili, piano Coached by William Wol!am Students in this performance are supported by the Robert Mann Endowed Scholarship for Violin and Chamber Studies, the Samuel and Mitzi Newhouse Scholarship, the Flavio Varani Scholarship in Piano, the Viola B. Marcus Memorial Scholarship, the Rachmael Weinstock Endowed Scholarship in Violin. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT LILLIAN FUCHS Hailed by Harold C. Schonberg in the New York Times in 1962 as “one of the best string players in America,” Lillian Fuchs (1902–1995) joined the chamber music and viola faculties at Manhattan School of Music in 1962, where she remained for almost 30 years. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 13, 2015 January 7, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Alan Gilbert To Conduct SILK ROAD ENSEMBLE with YO-YO MA Alongside the New York Philharmonic in Concerts Celebrating the Silk Road Ensemble’s 15TH ANNIVERSARY Program To Include The Silk Road Suite and Works by DMITRI YANOV-YANOVSKY, R. STRAUSS, AND OSVALDO GOLIJOV February 19–21, 2015 FREE INSIGHTS AT THE ATRIUM EVENT “Traversing Time and Trade: Fifteen Years of the Silkroad” February 18, 2015 The Silk Road Ensemble with Yo-Yo Ma will perform alongside the New York Philharmonic, led by Alan Gilbert, for a celebration of the innovative world-music ensemble’s 15th anniversary, Thursday, February 19, 2015, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, February 20 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, February 21 at 8:00 p.m. Titled Sacred and Transcendent, the program will feature the Philharmonic and the Silk Road Ensemble performing both separately and together. The concert will feature Fanfare for Gaita, Suona, and Brass; The Silk Road Suite, a compilation of works commissioned and premiered by the Ensemble; Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky’s Sacred Signs Suite; R. Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration; and Osvaldo Golijov’s Rose of the Winds. The program marks the Silk Road Ensemble’s Philharmonic debut. “The Silk Road Ensemble demonstrates different approaches of exploring world traditions in a way that — through collaboration, flexible thinking, and disciplined imagination — allows each to flourish and evolve within its own frame,” Yo-Yo Ma said. -

String Quartet in E Minor, Op 83

String Quartet in E minor, op 83 A quartet in three movements for two violins, viola and cello: 1 - Allegro moderato; 2 - Piacevole (poco andante); 3 - Allegro molto. Approximate Length: 30 minutes First Performance: Date: 21 May 1919 Venue: Wigmore Hall, London Performed by: Albert Sammons, W H Reed - violins; Raymond Jeremy - viola; Felix Salmond - cello Dedicated to: The Brodsky Quartet Elgar composed two part-quartets in 1878 and a complete one in 1887 but these were set aside and/or destroyed. Years later, the violinist Adolf Brodsky had been urging Elgar to compose a string quartet since 1900 when, as leader of the Hallé Orchestra, he performed several of Elgar's works. Consequently, Elgar first set about composing a String Quartet in 1907 after enjoying a concert in Malvern by the Brodsky Quartet. However, he put it aside when he embarked with determination on his long-delayed First Symphony. It appears that the composer subsequently used themes intended for this earlier quartet in other works, including the symphony. When he eventually returned to the genre, it was to compose an entirely fresh work. It was after enjoying an evening of chamber music in London with Billy Reed’s quartet, just before entering hospital for a tonsillitis operation, that Elgar decided on writing the quartet, and he began it whilst convalescing, completing the first movement by the end of March 1918. He composed that first movement at his home, Severn House, in Hampstead, depressed by the war news and debilitated from his operation. By May, he could move to the peaceful surroundings of Brinkwells, the country cottage that Lady Elgar had found for them in the depth of the Sussex countryside. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 No. 1, Spring 2015

New Horizons Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part II The Viola Concertos of J. G. Graun and M. H. Graul Unconfused The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Volume 31 Number 1 Number 31 Volume Turn-Out in Standing Journal of the American Viola Society Viola American the of Journal Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2015: Volume 31, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 9 Primrose Memorial Concert 2015 Myrna Layton reports on Atar Arad’s appearance at Brigham Young University as guest artist for the 33rd concert in memory of William Primrose. p. 13 42nd International Viola Congress in Review: Performing for the Future of Music Martha Evans and Lydia Handy share with us their experiences in Portugal, with a congress that focused on new horizons in viola music. Feature Articles p. 19 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II After a fascinating look at Borisovsky’s life in the previous issue, Elena Artamonova delves into the violist’s arrangements and editions, with a particular focus on the Glinka’s viola sonata p. 31 The Viola Concertos of J.G. Graun and M.H. Graul Unconfused The late Marshall ineF examined the viola concertos of J. G. Graul, court cellist for Frederick the Great, in arguing that there may have been misattribution to M. H. Graul. Departments p. 39 With Viola in Hand: A Passion Absolute–The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet The Absolute eroZ Quartet has captured the attention of violists in some 60 countries. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Tertis's Viola Version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to Clevelandclassical

Preview Heights Chamber Orchestra conductor's notes: Tertis's viola version of Elgar's Cello Concerto by Anthony Addison Special to ClevelandClassical An old adage suggested that violists were merely vio- linists-in-decline. That was before Lionel Tertis! He was born in 1876 of musical parents who had come to England from Poland and Russia and, at three years old, he started playing the piano. At six he performed in public, but had to be locked in a room to make him practice, a procedure that has actually fostered many an international virtuoso. At thirteen, with the agree- ment of his parents, he left home to earn his living in music playing in pickup groups at summer resorts, accompanying a violinist, and acting as music attendant at a lunatic asylum. +41:J:-:/1?<1>95@@1041?@A0510-@(>5:5@E;88131;2!A?5/@-75:3B5;85:-?45? "second study," but concentrating on the piano and playing concertos with the school or- chestra. As sometime happens, his violin teacher showed little interest in a second study <A<58-:01B1:@;8045?2-@41>@4-@41C-?.1@@1>J@@102;>@413>;/1>E@>-01 +5@4?A/4 encouragement, Tertis decided he had to teach himself. Fate intervened when fellow stu- dents wanted to form a string quartet. Tertis volunteered to play viola, borrowed an in- strument, loved the rich quality of its lowest string and thereafter turned the old adage up- side down: a not very obviously gifted violinist becoming a world class violist. But, until the viola attained respectability in Tertis’s hands, composers were reluctant to write for the instrument. -

Classical Music Manuscripts Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographical Sketches …………………………………………………………………... 2 Scope and Content …………………………………………………………………………... 13 Series Notes …………………………………………………………………………………... 13 Container List …………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Robert Ambrose …………………………………………………………………... 15 Florence Aylward …………………………………………………………………... 15 J.W.B. …………………………………………………………………………………... 15 Jean-Guillain Cardon …………………………………………………………………... 15 Evaristo Felice Dall’Abaco …………………………………………………………... 15 Alphons Darr …………………………………………………………………………... 15 P.F. Fierlein …………………………………………………………………………... 15 Franz Jakob Freystadtler …………………………………………………………... 16 Georg Golterman …………………………………………………………………... 16 Gottlieb Graupner …………………………………………………………………... 16 W. Moralt …………………………………………………………………………... 16 Pietro Nardini …………………………………………………………………………... 17 Camillo de Nardis …………………………………………………………………... 17 Alessandro Rolla …………………………………………………………………... 17 Paul Alfred Rubens …………………………………………………………………... 17 Camillo Ruspoli di Candriano …………………………………………………... 17 Domenico Scarlatti …………………………………………………………………... 17 Friederich Schneider …………………………………………………………………... 17 Ignaz Umlauf …………………………………………………………………………... 17 Miscellaneous Collections …………………………………………………………... 17 Unknown …………………………………………………………………………... 18 MS226-Classical Music Manuscripts Collection 1 University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION -

Lillian Fuchs: Violist, Teacher and Composer

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola Teodora Dimova Peeva Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Peeva, Teodora Dimova, "Lillian Fuchs: violist, teacher and composer; musical and pedagogical aspects of the 16 Fantasy études for viola" (2011). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3589. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3589 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. LILLIAN FUCHS: VIOLIST, TEACHER, AND COMPOSER; MUSICAL AND PEDAGOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE 16 FANTASY ÉTUDES FOR VIOLA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Teodora Peeva B.M., University of California, 2003 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 May, 2011 TO THE MEMORY OF MY PARENTS ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To David and the entire Weill family, for your unflagging encouragement and support. To Ms. Lori Patterson, for selflessly sharing your wisdom with me and for allowing me the pleasure of knowing you. My deepest gratitude goes to the members of my doctoral committee, for your contribution of time and knowledge in assisting with the completion of this monograph and for your willingness to serve. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 28 No. 1, Spring 2012

y t e i c o S a l o i V n a c i r e m A e h t Features: 1 f IVC 39 Review r e o b Bernard Zaslav: m From Broadway u l to Babbitt N a Sergey Vasilenko's 8 n Viola Compositions 2 r e m u u l o V o J Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2012 Volume 28 Number 1 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In Memoriam ~ IVC Host Letter Feature Articles p. 13 International Viola Congress XXXIX in Review: Andrew Filmer and John Roxburgh report from Germany p. 19 Bowing for Dollars: From Broadway to Babbitt: Bernard Zaslav highlights his career as Broadway musician, recording artist, and quartet violist p. 33 Unknown Sergey Vasilenko and His Viola Compositions: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives: Elena Artamonova uncovers works by Russian composer Sergey Vasilenko Departments p. 49 In the Studio: Yavet Boyadjiev chats with legendary Thai viola teacher Choochart Pitaksakorn p. 57 Student Life: Meet six young violists featured on NPR’s From the Top p. 65 With Viola in Hand: George Andrix reflects on his viola alta p. 69 Recording Reviews On the Cover: Karoline Leal Viola One Violist Karoline Leal uses her classical music background for inspiration in advertising, graphic design, and printmaking. Viola One is an alu - minum plate lithograph featuring her viola atop the viola part to Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. To view more of her art, please visit: www.karolineart.daportfolio.com. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 14 No. 2, 1998

JOURNAL ofthe AfrfERICAN ViOLA SOCIETY Section of THE INTERNATIONAL VIOI.A SOCIETY Association for the Promotion ofViola Performance and Research Vol. 14 No.2 1998 FEATURES 19 The Violin Making School of America Interview of Peter Paul Prier By David Dalton Viola Pedagogy: The Art and Value of Warming-Up By Christine Rutledge Music Insert: "Invocation for Violin and Viola" by Robert Mann AVS Chapters OFFICERS Peter Slowik President School of Music Northwestern University Evanston, IL 60201 (847) 491-3826 [email protected] William Preucil Vice President 317 Windsor Dr. Iowa City, IA 52245 Catherine Forbes Secretary 1128 Woodland Dr. Arlington, TX 76012 Ellen Rose Treasurer 2807 Lawtherwood Pl. Dallas, TX 75214 Thomas Tafton Past President 7511 Parkwoods Dr. Stockton, CA 95207 BOARD Victoria Chiang Donna Lively Clark Paul Coletti Ralph Fielding Pamela Goldsmith Lisa Hirschmugl John Graham Jerzy Kosmala Jeffrey Irvine Karen Ritscher Christine Rutledge Pamela Ryan Juliet White-Smith EDITOR, JAVS David Dalton Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 PAST PRESIDENTS Myron Rosenblum (1971-1981) Maurice W. Riley (1981-1986) David Dalton (1986-1990) Alan de Veritch (1990-1994) HONORARY PRESIDENT William Primrose ~Section of the International£ Viola-Gesellschaft The journal ofthe American Viola Society is a peer-reviewed publication of that organization and is produced at Brigham Young University, ©1985, ISSN 0898-5987. ]AVSwelcomes letters and articles from its readers. Editorial Office: School of Music Harris Fine Arts Center Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 (801) 378-4953 Fax: (801) 378-5973 [email protected] Editor: David Dalton Associate Editor: David Day Assistant Editor for Viola Pedagogy: Jeffrey Irvine Assistant Editor for Interviews: Thomas Tatton Production: Ben Dunford Advertising: Jeanette Anderson Advertising Office: Crandall House West (CRWH) Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 (801) 378-4455 [email protected] ]AVS appears three times yearly.