Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 107Th CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 107th CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 147 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, 2001 No. 115 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Also, we entreat You to please give Mr. FLETCHER. Mr. Speaker, I rise called to order by the Speaker pro tem- us Your dealing grace: wisdom for our today to thank a dear friend and class- pore (Mr. SHIMKUS). work, discernment for our decisions, mate, Reverend Roy Mays, for his f resources for our responsibilities, and beautifully insightful prayer opening joy for our journey. today’s session of the United States DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER In all these requests, Heavenly Fa- House of Representatives. PRO TEMPORE ther, we pray that Your will be done, The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- Within the hallowed walls of this and we accept that Your grace is suffi- Chamber, my colleagues and I gather fore the House the following commu- cient. For thine is the kingdom and the nication from the Speaker: to attend to the business of this great power and the glory, forever and ever. Nation. Since the beginning of our de- WASHINGTON, DC, Amen. September 6, 2001. mocracy, we have begun each day’s f I hereby appoint the Honorable JOHN work petitioning our creator that we SHIMKUS to act as Speaker pro tempore on THE JOURNAL might know truth and have the wisdom this day. and understanding to rightfully fulfill The SPEAKER pro tempore. The J. -

Sự Thật Về Lý Tống

Sự Thật về Lý Tống 1 Sự Thật về Lý Tống Thay lời tựa Tập sách “SỰ THẬT về LÝ TỐNG” là sự góp mặt có chọn lựa của nhiều tác giả qua các bài viết riêng lẻ đã từng xuất hiện trên các diễn đàn Internet và trên các tở báo. Tuy nhiên để cho độc giả và đồng hương Việt Nam hải ngoại vùng Bắc Cali, và tất cả qúi đồng hương Việt Nam cư ngụ tại các địa phương cũng như các quốc gia có người Việt tị nạn Cộng Sản được cái nhìn tổng quát về Lý Tống, đồng thời biết rõ thêm những nguyên nhân và động lực nào mà Lý Tống đã tác yêu, tác quái, lừa thầy, phản bạn, vong ân bội nghiã, bịp bợm trong suốt thời gian dài. Nhóm chủ trương tập sách này đã sắp xếp, hệ thống hóa những bài viết của các cây bút trên diễn đàn, các bài viết cũng đã phân tích những tác hại qua những bài viết do Lý Tống viết ra, để đồng bào hải ngoại rõ thêm bộ mặt và tâm địa của Lý Tống qua “sự nghiệp vĩ đại anh hùng chống cộng toàn cầu…..”. Chúng ta đã r ời bỏ đất nước Việt Nam thân yêu, sống tản mác khắp trên thế giới, nhưng chúng ta không quên trách nhiệm của chúng ta đối với đất nước và Dân tộc Việt Nam. Người Dân ở trong nước hay ở Hải ngoại phải có nhiệm vụ lật đổ chế độ Cộng Sản phi nhân để thiết lập cơ chế dân chủ, tự do, hòa bình, ấm no thực sự cho dân tộc Việt Nam đã quá trầm luân đau khổ vì đ ảng cướp Cộng Sản Việt Nam gây ra hơn suốt 35 năm triền miên thống hận. -

(210) «Nroexpediente»

DIP Weekly Official Gazette, Week 33 of 2016, Aug 19th, 2016 1- 68232/D /2016 2- 24/03/2016 3- Mrs. CHHOUR VANMALY 4- Kourothan Village, Sangkat Ou Ambel, Serei Saophoan City, Banteaymeanchey Province, Cambodia 5- Cambodia 6- Mrs. CHHOUR VANMALY 7- Kourothan Village, Sangkat Ou Ambel, Serei Saophoan City, Banteaymeanchey Province, Cambodia 8- 60624 9- 16/08/2016 10- 11- 43 12- 24/03/2026 __________________________________ 1- 62375 /2015 2- 25/02/2015 3- SUN PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRIES LIMITED 4- SPARC, Tandalja, Vadodara- 390 020, Gujarat, India 5- India 6- LPN IP AGENCY 7- #62G, Street 598, Sangkat Boeung Kak 2, Khan Tuol Kork, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 8- 60625 9- 16/08/2016 10- SOFURA 11- 5 12- 25/02/2025 __________________________________ 1- 67425/D /2016 2- 27/01/2016 3- Mr. LY THEANG SENG 4- Vihea chen village, Svaydongkum commune, Siemreap ville, Siemreap province, Cambodia 5- Cambodia 6- Mr. LY THEANG SENG 7- Vihea chen village, Svaydongkum commune, Siemreap ville, Siemreap province, Cambodia 8- 60626 9- 16/08/2016 10- 11- 30 12- 27/01/2026 1 DIP Weekly Official Gazette, Week 33 of 2016, Aug 19th, 2016 __________________________________ 1- 67475/D /2016 2- 29/01/2016 3- KOHMEAS PRAK (CAMBODIA) TRADING., LTD. 4- No 168, Street 1984, Phum Phnom Penh Thmei, Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmei I, Khan Sen Sok, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 5- Cambodia 6- KOHMEAS PRAK (CAMBODIA) TRADING., LTD. 7- No 168, Street 1984, Phum Phnom Penh Thmei, Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmei I, Khan Sen Sok, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 8- 60627 9- 16/08/2016 10- 11- 30 12- 29/01/2026 __________________________________ 1- 67426/D /2016 2- 27/01/2016 3- MELBOURNE ESTATE Co.,Ltd 4- Kasekam Village, Srange Commune, Siemreap Town, Siernreap Province, Cambodia 5- Cambodia 6- MELBOURNE ESTATE Co.,Ltd 7- Kasekam Village, Srange Commune, Siemreap Town, Siernreap Province, Cambodia 8- 60628 9- 16/08/2016 10- 11- 35 12- 27/01/2026 __________________________________ 1- 67433/D /2016 2- 27/01/2016 3- Mr. -

VIETNAM Page 1 of 19

VIETNAM Page 1 of 19 Recent Reports Support HRW About HRW Site Map August 1995 Vol. 7, No. 12 VIETNAM HUMAN RIGHTS IN A SEASON OF TRANSITION: Law and Dissent in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam INTRODUCTION Vietnam has entered an era of rapid economic and social transformation, heralded by the opening of its economy, its entry into ASEAN and the resumption of diplomatic relations with the United States. At the same time, the government and the Vietnam Communist Party have sought to maintain a firm grip on political control. This stance has produced a steady stream of dissent in recent years, to which the government has responded harshly. Those who have publicly questioned the authority of the Party have been detained and imprisoned, be they proponents of multi-party democracy, advocates of civil and political rights, or religious leaders seeking greater autonomy from official control. Without taking a position as to the merits of these views, Human Rights Watch maintains that individuals have the right to peacefully express them under international human rights law, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights to which Vietnam is a signatory. This report does not attempt to cover human rights conditions in Vietnam comprehensively, but rather focuses on several critical areas of concern: the legal system as it affects human rights and the continuing problem of detention for political or religious dissent. While the government of Vietnam has shown energy in instituting legal reform, its legal system remains politicized, and it has had difficulty in implementing new laws in such a way as to fortify basic civil and political rights. -

The Foreign Service Journal, October 1998

DRUG TESTING AT STATE NAIROBJ/DAR ES SALAAM VIETNAM SHADOWS CARIBBEAN POLICY: DOWN THE DRAIN How a Vital Region Dropped Off the Map Affordable Luxury If you are relocating, a business traveler or need temporary housing, we ojfer furnished apartments with all of the comforts of home. AVALON CORPORATE APARTMENT HOMES ARE A MORE SENSIBLE AND AFFORDABLE ALTERNATIVE TO A HOTEL ROOM. • Located minutes from • 2 miles from NFATC Pentagon, Washington, DC and National Airport. • Controlled access entry throughout building. • Luxurious one and two bedroom apartments • Our amenity package completely furnished and includes: outdoor pool, accessorized with fully and spacious Nautilus equipped gourmet fitness center. kitchens and washers and dryers. • Minutes from Ballston Metro. • Free cable TV. • Free underground parking. • Within walking distance of department stores, • Cats welcome. specialty shops and Washington Towers restaurants. • 5p.m. check-in time. • Washington Towers is • 30-day minimum stay. adjacent to bike/jogging trail. Avalon at Ballston No matter which Avalon location you choose, you will be impressed.' Washington Towers 4650 N. Washington Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201 703-527-4409 or Fax 703-516-4369 Quincy Towers 1001 North Randolph St., Arlington, VA 22201 703-528-4600 or Fax 703-527-2356 Vermont Towers 1001 North Vermont St., Arlington, VA 22201 703-522-5550 or Fax 703-527-8731 Are you hearing an old cliche from your local insurance company? By purchasing insurance from foreign companies you probably think that your claims will be settled faster or your premiums will cost less. The reality is that these companies often find any excuse to delay a claim — and we've heard them all! Clements is an American company with 50 years experience insuring the Foreign Service at home and abroad. -

A Study of Vietnamese Diaspora Intellectuals

A STUDY OF VIETNAMESE DIASPORA INTELLECTUALS FROM VICTIMIZATION TO TRANSNATIONALISM: A STUDY OF VIETNAMESE DIASPORA INTELLECTUALS IN NORTH AMERICA BY NHUNG (ANNA) VU, B.A. (Hons.), M.A. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES OF MCMASTER UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY © Copyright by Nhung (Anna) Vu, June 2015 All Rights Reserved Doctor of Philosophy (2015) McMaster University (Sociology) Hamilton, Ontario, Canada TITLE: From Victimization to Transnationalism: A Study of Vietnamese Diaspora Intellectuals in North America AUTHOR: Nhung (Anna) Vu B.A. (Hons.), M.A. SUPERVISOR: Dr. Neil McLaughlin NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 317 ii Abstract The objective of this thesis is to examine the issue of identity construction among Vietnamese intellectuals in North America. How is the way in which they construct their identity connected to their position(s) on the Vietnam War, anti-communist community discourse, and memory/commemoration, especially with respect to the contentious debate about which flag represents Vietnam today? Vietnamese Diaspora Intellectuals (VDI) are an understudied group, and I hope my research will help to fill this gap, at least in part, and also serve as a catalyst for further investigation. In my attempt to address this neglected area of study, I am bringing together two bodies of literature: diaspora studies and literature on identity formation among intellectuals. The intersection between these two areas of scholarship has received relatively little attention in the past, and it deserves further consideration, because intellectuals are so often in a position to serve as carriers and disseminators of new ideas, as well as facilitators in conflict resolution. -

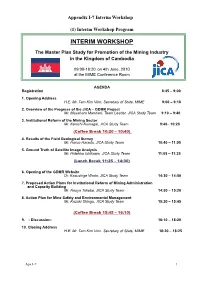

Interim Workshop

Appendix I-7 Interim Workshop (1) Interim Workshop Program INTERIM WORKSHOP The Master Plan Study for Promotion of the Mining Industry in the Kingdom of Cambodia 09:00-18:20, on 4th June, 2010 at the MIME Conference Room AGENDA Registration 8:45 – 9:00 1. Opening Address H.E. Mr. Tam Kim Vinn, Secretary of State, MIME 9:00 – 9:10 2. Overview of the Progress of the JICA – GDMR Project Mr. Masaharu Marutani, Team Leader, JICA Study Team 9:10 – 9:40 3. Institutional Reform of the Mining Sector Mr. Kenichi Kumagai, JICA Study Team 9:40– 10:20 (Coffee Break 10:20 – 10:40) 4. Results of the Field Geological Survey Mr. Haruo Harada, JICA Study Team 10:40 – 11:05 5. Ground Truth of Satellite Image Analysis Mr. Hidehiro Ishikawa, JICA Study Team 11:05 – 11:25 (Lunch Break 11:25 – 14:30) 6. Opening of the GDMR Website Dr. Kazushige Wada, JICA Study Team 14:30 – 14:50 7. Proposed Action Plans for Institutional Reform of Mining Administration and Capacity Building Mr. Naoya Takebe, JICA Study Team 14:50 – 15:20 8. Action Plan for Mine Safety and Environmental Management Mr. Kazuki Shingu, JICA Study Team 15:20 – 15:45 (Coffee Break 15:45 – 16:10) 9. - Discussion- 16:10 – 18:20 10. Closing Address H.E. Mr. Tam Kim Vinn, Secretary of State, MIME 18:20 – 18:25 Apx I-7 1 (2) The List of Participants The List of Participants on the Interim Workshop on 4th June, 2010 No. Name Title Organization 1 H.E Mr. -

Who Was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship Between History and Cultural Memory Evyn Lê Espiritu Pomona College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2013 “Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory Evyn Lê Espiritu Pomona College Recommended Citation Lê Espiritu, Evyn, "“Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?”: Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory" (2013). Pomona Senior Theses. 92. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/92 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Who was Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn?” Theorizing the Relationship between History and Cultural Memory by Evyn Lê Espiritu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Bachelor’s Degree in History Pomona College April 12, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 A Note on Terms 3 In the Beginning: Absence and Excess 4 Constructing a Narrative: Situating Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn 17 Making Space in the Present: South Vietnamese American Cultural Memory Acts 47 Remembering in Private: The Subversive Practices of Colonel Hồ Ngọc Cẩn’s Relatives 89 The End? Writing History and Transferring Memory 113 Primary Sources 116 Secondary Sources 122 1 Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the advice and support of several special individuals. In addition to all my interviewees, I would like to especially thank: my thesis readers, Prof. Tomás Summers Sandoval (History) and Prof. Jonathan M. Hall (Media Studies), for facilitating my intellectual development and encouraging interdisciplinary connections my mother, Dr. -

Proquest Dissertations

The role of cultural factors affecting the academic achievement of Vietnamese/refugee students: A case study Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nguyen, Sang Ngoc Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 13:51:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282908 THE ROLE OF CULTURAL FACTORS AFFECTING THE ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT OF VIETNAMESE/REFUGEE STUDENTS: A CASE STUDY by Sang Ngoc Nguyen Copyright @ Sang Ngoc Nguyen 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE, READING AND CULTURE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College The University of Arizona 2 00 5 UMI Number: 3205466 Copyright 2004 by Nguyen, Sang Ngoc All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3205466 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Committee for Little Saigon

tt!;;.o/07 Cfr ~/-...,f':., , "') " .', 4£'7 -:>, 4??t/ ?\ Committee For Little Saigon ~'J' ./ 220 Leo Ave., Suite B /y ., San Jose, CA 95112 .<J ••,.1: u.". I' November 12th, 2007 1>'" Dear Honorable Mayor Reed and San Jose City Council Members, We would like to present you with information why the majority of Vietnamese-American residents in San Jose strongly wish that the proposed business district named "Little Saigon," including: • Petition to adopt the name Little Saigon (we have collected more than 2,000 signatures from the residents of San Jose and already provided your office with copies ofthese) • An analysis on economic impacts on different choices ofthe name (Little Saigon vs. New Saigon) • Reasons why the area should be named Little Saigon and NOT New Saigon • List of more than 100 elected officials, Vietnamese associations and businesses in support of the name Little Saigon • Clarification Letters from members of organizations whose chairman should sign the petition to endorse New Saigon ONLY as individual (not as an organization as a whole) • Rectification Letters from various Vietnamese community leaders for having mistakenly supported the name New Saigon and who are now supporting the name Little Saigon for the designated business district. • Letters from Vietnamese Communities in the United States supporting "Little Saigon" • Letter from Janet Nguyen Supervisor of Orange County supporting "Little Saigon" • Letter from Catholic Priest Nguyen Huu Le supporting "Little Saigon" • The survey results from: a.-San Jose mercury news, 2 surveys b.-RDA survey c.- Survey result from Minh Duong, San Jose Dist. 8 candidate d.-Nguoi Viet Online survey from Southern california e.-Pictures of the Sept 23rd 2007, General meeting of Committee for Little Saigon We hope that you will find these documents to be useful in making your decision to support adopting the name "Little Saigon" for this designated business district. -

Farmers Build March in Atlanta to Press Fight

· AUSTRALIA $2.50 · BELGIUM BF60 · CANADA $2.50 · FRANCE FF1 0 · ICELAND Kr200 · NEW ZEALAND $2.50 · SWEDEN Kr12 · UK £1.00 · U.S. $1.50 THE A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 64 NO.2 JANUARY 17. 2000 Chechnya stakes rise Farmers build march for Moscow, in Atlanta to press fight BY MARY MARriN Washington WASHINGTON, D.C.--The Black Farm- . · ers andAgriculturalistsAssociation (BFAA) BYPATRICKO'NEILL has issued a call for farmers and supporters to "We have been fighting all over Chechnya, join their contingent in the January 17 Martin but Grozny,is the first place we have come Luther King Day march in Atlanta. across such intense resistance," said Russian The farmers are marching to protest wors army Lt. Konstantin Kukhlovets January l. ening conditions they face; refusal ofthe gov The Russian forces that invaded the territory ernment to implement a March 1999 consent ofChechnya in September are engaged in tough decree settlement that is supposed to award combat in the capital and in the south near the damages to farmers who have suffered racist Caucasus mountains. discrimination by the government; and con The day before, President Boris Yeltsin re tinuing harassment at the hands of.govern signed from the post he has held for over nine ment farm agency representatives. years. "I have signed a decree placing the du Melvin Bishop, a cattle farmer and presi ties of the president ofRussia on the head of dent of the Georgia chapter ofBFAA, said, government, Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin," . "Working people in the cities have a stake in saidYeltsin. -

Lý Tống Ở Little Saigon Phóng Sự Ảnh: Dân Huỳnh & Văn Lan/Người Việt April 21, 2019

‘Ó Đen’ Lý Tống sẽ được đưa về an táng tại Little Saigon Đỗ Dzũng/Người Việt Ông Lý Tống đứng tại xa lộ 15, lối vào đại lộ Ej Cajon, San Diego, hôm 1 Tháng Hai. (Hình: Nhân Phạm/Người Việt) WESTMINSTER, California (NV) – Thi hài “Ó Đen” Lý Tống sẽ được đưa về an táng ở Little Saigon, thay vì San Diego, ông Cù Thái Hòa, hội trưởng Hội Ái Hữu Không Quân San Diego, xác nhận với nhật báo Người Việt hôm Thứ Bảy, 6 Tháng Tư. Ông cũng cho biết, “anh em Không Quân đang họp thảo luận chi tiết, có thể sẽ đưa anh Tống về Little Saigon vào ngày Thứ Sáu, 19 Tháng Tư, và tang lễ này sẽ do Hội Ái Hữu Không Quân San Diego tổ chức.” Ông Phát Bùi, chủ tịch Cộng Đồng Người Việt Quốc Gia Nam California kiêm nghị viên Garden Grove, cũng xác nhận với Người Việt tin này. “Chúng tôi dự định sẽ làm đám tang anh Tống trong hai ngày 20 và 21 Tháng Tư. Tôi có nói chuyện với anh Hứa Trung Lập, người chuyên phụ trách mai táng, và được anh bảo đảm sẽ có đất cho anh Tống,” ông Phát nói. Đứng cùng với ông Phát khi dự lễ viếng danh hài Anh Vũ hôm Thứ Bảy, tỷ phú Hoàng Kiều cho biết ông “sẵn sàng đài thọ tài chính để mua miếng đất cho anh Tống.” Ông nói thêm: “Chúng ta phải kiếm một miếng đất đẹp và rộng cho anh Tống vì anh xứng đáng được như vậy.” Ông Lý Tống qua đời lúc 9 giờ 16 phút tối Thứ Sáu, 5 Tháng Tư, tại bệnh viện Sharp Memorial Hospital, San Diego, vì xơ phổi, hưởng thọ 73 tuổi.