Buttevant Town Walls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bureauofmilitaryhistory1913-21 Burostaremileata1913-21 Original No

BUREAUOFMILITARYHISTORY1913-21 BUROSTAREMILEATA1913-21 ORIGINAL NO. W.S. 1.133 ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,133 Witness Miss Annie Barrett, Killavullen, Co. cork. Identity. Intelligence Agent, Mallow Battalion, Cork II Brigade. Subject. Intelligence work Mallow Battalion, Cork II Brigade, 1918-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2419 Form B.S.M.2 BUREAUOFMILITARYHIGTORY1913-21 RUROSTAIREMILLATA1913-21 ORIGINAL NO. W.S. 1.133 STATEMENTBY MISS ANNIE BARRETT, Killavullen, County Cork. I was born at Killavullen, County Cork, on 24th September, 1888. My father was a Fenian. He escorted O'Neill Crowley from his hiding place in Glenagare to Kilclooney Wood in 1867. I was educated at Killavullen National School where I attended until I was about 16 years of age. I then went to the Munster Civil Service College where I remained for about 11/2years. I entered the Post Office Service as a telephonist at Killarney in 1906.. After about six months I was transferred to Mallow. Early in 1919 I was appointed Supervising Telephonist at Mallow and I continued to serve in this capacity until I was superannuated in 1945. In the years prior to and following 1916 I took a keen interest in the national cultural organisations in the district. I was a member of the Gaelic League and was Captain of the Thomas Davis Camogie Club in 1914. My first contact with the Irish Volunteer Organisation was made through my brother who was a wireless operator. This was early in 1918 when he put me in touch with Tom Hunter and Danny Shinnick who were the Volunteer leaders in the Castletownroche-Killavullen area at the time. -

Cork-Aul-Records-1981-1990.Pdf

Cork AUL Records Originally compiled by Billy Lyons and updated by Barry Peelo 1980/81 Premier League Casement Celtic St Mary’s League 1 Northvilla Ballincollig League 2 Ballyvolane Grangevale League 3 Telford United Park United Youths 1 Tramore Athletic St Mary’s Youths 2 Castleview Western Rovers AOH Cup St Mary's Temple United County Cup Carrigaline United Ard-na-Laoi Saxone Cup Farnanes Glenview O’Keeffe Cup Grattan United Casement Celtic Murphy Cup St Mary’s Tramore Athletic Coca Youths 1 League Cup Ballincollig Rockmount Premier League Cup Cobh Ramblers Casement Celtic 1st Division League Cup Grattan United Kinsale 2nd Division League Cup Carrigaline United Glenview 3rd Division League Cup Waterloo Killowen Youths 2 League Cup Youghal Crofton Celtic Tayto Cup Cork AUL 1981/82 FAI Youths Cup Tramore Athletic Athlone FAI Under17 Cup Home Farm (Dub) Springfield Premier League St Mary's Casement Celtic League 1 St John Bosco's Hillington League 1 A Carrigaline United Victoria Athletic League 1 B Grattan United Glenvale League 2 Central Rovers Albert Rovers League 2 A Kilreen Celtic Waterloo League 2 B Ballincollig United Skibbereen Dynamos League 3 Mallow United Killavullen League 3 A Killeady United Carrigaline United League 3 B Avondale Leeside Youths 1 Tramore Athletic Springfield Youths 2 Everton Midleton Youths 2A Grattan United Coachford AOH Cup Tramore Athletic Temple United St Michael's Cup Ballincollig St Mary’s County Cup Carrigaline United Farnanes Saxone Cup Carrigaline United Skibbereen Dynamos President's Cup Douglas Hall -

Dovecote, Ballybeg Priory

Hidden gems and Forgotten People BALLINCOLLIG HERITAGE ASSOCIATION THE DOVE-COTE, BALLYBEG PRIORY, CO CORK Ballybeg Priory is a 13th century priory situated near the town of Buttevant, County Cork, which lies between Cork and Limerick on the N20. It was founded by Philip de Barry in 1229 as an Augustinian order and named after the martyred archbishop of Canterbury, St. Thomas à Becket. Ballybeg was an extensive foundation, the priory church measuring some 166 feet (51 m) in length and 26 feet (7.9 m) in width. The priory is now in ruins but located away from the main ecclesiastical buildings, standing intact in the middle of a field is the most noteworthy remaining structure on the site, a round tower dovecote. It is a truly remarkable structure. Inside, the walls are built in square compartments in regular tiers to a height of fifteen feet. There are some 352 niches, divided into eleven tiers each containing 32 compartments. It opens to the sky. The dovecote was important as a source of revenue for the priory as its main agricultural purpose was the production of fertiliser. Pigeon fertiliser was essential for herb gardens and economically more highly valued than equivalents produced by cattle, sheep or pigs. It was also essential for the successful growing of hemp, which was widely used for cloth, rope and sack making. A string course around the circumference of the building served not only as a structural strengthening of the building but also to prevent weasels, or other vermin from scaling the walls to the entrances. -

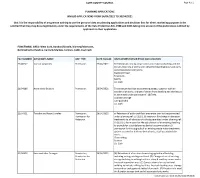

Invalid from 24/04/2021

CORK COUNTY COUNCIL Page No: 1 PLANNING APPLICATIONS INVALID APPLICATIONS FROM 24/04/2021 TO 30/04/2021 that it is the responsibility of any person wishing to use the personal data on planning applications and decisions lists for direct marketing purposes to be satisfied that they may do so legitimately under the requirements of the Data Protection Acts 1988 and 2003 taking into account of the preferences outlined by applicants in their application FUNCTIONAL AREA: West Cork, Bandon/Kinsale, Blarney/Macroom, Ballincollig/Carrigaline, Kanturk/Mallow, Fermoy, Cobh, East Cork FILE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME APP. TYPE DATE INVALID DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION 21/00242 Corran Carpentry Permission 27/04/2021 Demolition of existing single storey extension to dwelling and the construction of a 2 storey semi-detached dwellinghouse and carry out all associated site works Blackrock Road Town Lots Bantry Co. Cork 21/04886 Anna Marie Buckley Permission 26/04/2021 To construct dwelling incorporating garage, together with all ancillary site works, change of design from dwelling and site layout as permitted under planning ref. 18/7040. Coolnashamroge Carrigadrohid Co. Cork 21/04921 Timothy and Aoise Crowley Permission, 26/04/2021 a) Retention of additional floor area extra over to that permitted Permission for under planning ref: 0713391, b) retention for change in elevation Retention treatments to all elevations to those permitted under planning ref: 0713391 c) Permission for the sub division of an existing dwelling to provide for a standalone residential accommodation d) permission for the upgrade of an existing waste water treatment system to cater for both residential units, e) all associated site works. -

Buttevant SH Stanley Hincliffe CF AMH AM Hewson CF

CONTENTS Page No Introduction 1 Distribution ii Ministers' Initials 11 Transcript of the Register 1--3 Alphabetical Index of Entries in the Registers 4 INTRODUCTION Whilst researching the history of my family in the Publlc Record Office at Kew, I noticed a reference to this Register of Baptisms (WO L56/4) in the guide to War Office files. It is one of only two Trish registers in WO 156. I thought that the information in the Register should be more widely available; this transcript is the resul.t. As with all documents of this nature the original should be consulted to confi-rm that entries have been transcribed and indexed accurately. The following specific points should be borne in mind when using the transcript: Dates AI1 dates have been standardised as follows; day in numbers, month in three letters (abbreviated as necessary), year. Additional Information Marginal notes and comments from the Registers appear in the text or as footnotes. Transcrj-ber's Observations The first five entries are for adults, t the occupation recorded refers to the individuals themselves and not their fathers. London SMW Dec L998 DISTRTBUTION Copies of this document have been distributed to the following: Representative Church Body Library, Dublin Society of Genealogists Lancashire Family History Society MINISTERS' INITIALS HOL HO Luckly CF RDG RD Grindley CF AWFO AWF OTT CF ,JWWS lTW Wallace-Smyth CF INHC INH Cotter Rector of Buttevant SH Stanley Hincliffe CF AMH AM HewsoN CF LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Bks Barracks Qtrs Quarters 1a o o ol (n. a c./) Fl FlO(9EqtrrBBFF -

A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork

Munster Technological University SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit Masters Engineering 1-1-2019 A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork Liam Dromey Cork Institute of Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Structural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Dromey, Liam, "A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy Based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork" (2019). Masters [online]. Available at: https://sword.cit.ie/engmas/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering at SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters by an authorized administrator of SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Civil, Structural and Environmental Engineering A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Liam Dromey Supervisors: Kieran Ruane John Justin Murphy Brian O’Rourke __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract A Bridge Rehabilitation Strategy based on the Analysis of a Dataset of Bridge Inspections in Co. Cork. Ageing highway structures present a challenge throughout the developed world. The introduction of bridge management systems (BMS) allows bridge owners to assess the condition of their bridge stock and formulate bridge rehabilitation strategies under the constraints of limited budgets and resources. This research presents a decision-support system for bridge owners in the selection of the best strategy for bridge rehabilitation on a highway network. The basis of the research is an available dataset of 1,367 bridge inspection records for County Cork that has been prepared to the Eirspan BMS inspection standard and which includes bridge structure condition ratings and rehabilitation costs. -

Parish Diocese Event Starts Ends Notes Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms

Parish Diocese Event Starts Ends Notes Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1877 Aghabullog Cloyne Burials 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Burials 1864 1879 Aghabullog Cloyne Marriages 1808 1864 Aghabullog Cloyne Marriages 1864 1882 Aghabullog Cloyne Notes surnames as Christian names Aghada Cloyne Baptisms 1838 1864 Aghada Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1902 Aghada Cloyne Burials 1838 1864 Aghada Cloyne Burials 1864 1914 Aghada Cloyne Combined 1729 1838 gaps 1737-60, 1770-75, 1807-1814 Aghada Cloyne Marriages 1839 1844 Aghada Cloyne Marriages 1845 1903 Aghern Cloyne Marriages 1846 1910 Aghern Cloyne Marriages 1911 1980 Aghada Cloyne MI Notes Ahinagh Cloyne MI Notes Ballyclough Cloyne Baptisms 1795 1864 Ballyclough Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1910 & 1911 to 1920 left unscanned Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1799 1830 extracts only Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1831 1864 Ballyclough Cloyne Burials 1864 1920 Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1801 1840 extracts only Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1831 1844 Ballyclough Cloyne Marriages 1845 1900 Ballyclough Cloyne Recantation 1842 Ballyhea Cloyne Baptisms 1842 1864 Ballyhea Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1910 1911 to 1950 left unscanned Ballyhea Cloyne Burials 1842 1864 Ballyhea Cloyne Burials 1864 1920 gap 1903 & 1904 Ballyhea Cloyne Combined 1727 1842 Ballyhea Cloyne Marriages 1842 1844 Ballyhea Cloyne Marriages 1845 1922 gap 1900 to 1907 Ballyhooly Cloyne Baptisms 1789 1864 extracts only Ballyhooly Cloyne Baptisms 1864 1900 only partial Ballyhooly Cloyne Burials 1785 1864 extracts only Ballyhooly Cloyne -

Community Groups Awarded Funding North Cork

1 Group Name and Address M/D Applied for overall cost Approved 82nd Cork Rathcormac Scout Group Fermoy €4,500.00 €4,500.00 €3,000.00 Purchase of storage facility Ballindangan Community Council Fermoy €8,000.00 €8,000.00 €8,000.00 Refurbishment of community hall Bartlemy Parish Hall, Bartlemy, Fermoy, Co. Cork Fermoy €10,601.92 €10,601.92 €10,500.00 Purchase of 80 chairs and repair of stage Blackwater Search & Rescue c/o Rathealy Road, Fermoy, Co Cork Fermoy €22,928.00 €22,928.00 €20,000.00 Purchase of equipment Bride Rovers GAA Club, Bridgelands West, Rathcormac, Co. Cork Fermoy €3,500.00 €3,500.00 €1,000.00 Purchase of signage Brigown Arts & Heritage Project (CLG), Mulberry House, Mulberry Lane, Mitchelstown, Co. Cork Fermoy €25,000.00 €38,476.50 €20,000.00 Refurbishment of building CASTLELYONS COMMUNITY CENTRE Fermoy €5,879.00 €5,879.00 €4,000.00 Purchase furniture and equipment Castlelyons Pitch and Putt Fermoy €9,750.00 €9,750.00 €5,000.00 Purchase of lawnmower Charleville Community Hall, Chapel Street, Charleville, Co. Cork Fermoy €12,172.44 €12,172.44 €12,000.00 Refurbishment of community hall Charleville Rugby Club, Shandrum, Charleville, Co Cork Fermoy €25,000.00 €30,500.00 €6,000.00 Tarmac car park/lawnmower Charleville Tidy Towns, c/o Aine McMahon, Rathgoggin South, Charleville, Co. Cork (1) Fermoy €25,000.00 €25,000.00 €20,000.00 Purcase of benches, planters and plants Conna Community Council Fermoy €25,000.00 €31,600.00 €18,000.00 Development of community facilities DBH Community Responder Scheme, c/o Gerard Sheehan, Kilmacroom, Doneraile, Co Cork. -

Report by Commission of Investigation Into Catholic Diocese of Cloyne

Chapter 1 Overview Introduction 1.1 The Dublin Archdiocese Commission of Investigation was established in March 2006 to report on the handling by Church and State authorities of a representative sample of allegations and suspicions of child sexual abuse against clerics operating under the aegis of the Archdiocese of Dublin over the period 1975 - 2004. The report of the Commission was published (with some redaction as a result of court orders) in November 2009. Towards the end of its remit, on 31 March 2009, the Government asked the Commission to carry out a similar investigation into the Catholic Diocese of Cloyne. 1.2 During the Cloyne investigation the Commission examined all complaints, allegations, concerns and suspicions of child sexual abuse by relevant clerics made to the diocesan and other Catholic Church authorities and public and State authorities in the period 1 January 1996 – 1 February 2009. 1.3 This report deals with the outcome of the Cloyne investigation. In Chapters 2 – 8, the report outlines how the Commission conducted the investigation; the organisational structures of the Diocese of Cloyne and the relevant State authorities, that is, the Gardaí, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) and the health authorities; and the general background to the handling of complaints including an outline of the canon law and procedures involved and the financing of the costs involved. 1.4 Chapters 9 – 26 describe the cases of 19 clerics about whom there were complaints, allegations or concerns in the period 1 January 1996 – 1 February 2009. Below the Commission gives an overview of what these cases show. -

TITLE INDEX the Title Index Alphabetically Lists the Exact Titles As Given on the Maps Cataloged in Parts One and Two

TITLE INDEX The title index alphabetically lists the exact titles as given on the maps cataloged in Parts One and Two. Therefore, “A New Map of Ireland...” and “The New Map of Ireland...” are located in the title index under “A” and “T” respectively; a sixteenth-century map of “Vltonia” or “Vdrone” is found under “V”; and foreign titles such as “L’Irlanda” and “De Custen...” appear alphabetically under “L” and “D”. The title “Ireland,” as a single word, is found on over 220 maps in Parts One and Two. In the title index, therefore, “Ireland” has been further identified by both the name of the author in alphabetical order and publication date. A A Chart Of The Bay Of Galloway And River Shannon.....1457, 1458, 1459, 1460, 1461, 1462, 1463 A Chart of the Coasts of Ireland and Part of England.....208, 237, 239, 283, 287, 310, 327, 381, 384 A Chart of the East side of Ireland.....1604, 1606, 1610 A Chart Of The North-West Coast Of Ireland.....1725, 1726, 1727, 1728, 1729, 1730, 1731 A Chart Of The Sea-Coasts Of Ireland From Dublin To London-Derry.....1595, 1596, 1597, 1598, 1599, 1600, 1601 A Chart of the Southwest side of Ireland.....1662, 1663, 1664 A Chart Of The West and South-West Coast Of Ireland.....1702, 1703, 1704, 1714 A Chart of the West Coast of Ireland.....1681, 1684, 1695 A Compleat Chart Of The Coasts Of Ireland.....249 A Correct Chart of St. George's Channel and the Irish Sea... 271, 272 A Correct Chart of the Irish Sea.....1621 A Correct Map Of Ireland Divided into its Provinces, Counties, and Baronies.....231 A Discription -

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU of MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT by WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,051 Witness Timothy D. Crimmins, K

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1,051 Witness Timothy D. Crimmins, Kilbolane Milford, Charleville, Co. Cork. Identity. O/C. Engineers, Charleville Batt'n. Cork II Brigade. Battalion O.C. First Aid. Subject. Irish Volunteers, North-East Cork, 1916-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.2355 FormB.S.M.2 STATEMENT BY TIMOTHY D. CRIMMINS, Kilbolane, Milford, Charleville, Co. Cork. I was born in New York City in the year 1896. My father was head foreman for the contracting firm of Thomas E. Crimmins. When he retired he came back to Ireland to live. My father (like most of the people of the district - Kilbolane, Milford) was a supporter of John E. Redmond. He was also a member of the A.O.H. My first connection with any national organisation was with the Irish Volunteers, which I joined in Milford in 1916. The Volunteers were formed by Jim Brislane, Seán O'Dea and Larry Hedivan. Also in the unit were Jerry Falvey, John Manahan, Denis Noonan, Jim Coughlan and Patrick Fitzgibbon. The strength of the unit was about 14 at this time. Foot drill and parades were held in the fields about two nights each week, and occasionally on Sundays the unit would go on a route march to neighbouring units. Drill instruction was carried out by John Drew - an ex British soldier. He was only with us for a few weeks when Jerry Falvey was elected to take charge. He was the only officer at this time. -

Title Cork Archaeological Investigations Alternative Title GIS

Title Cork Archaeological Investigations Alternative Title GIS Dataset of Archaeological Excavations Abstract Cork County Council commissioned a GIS dataset of licensed archaeological excavations and investigations within Bandon Electoral Area and the fourteen towns of Bandon, Buttevant, Castlemartyr, Clonakilty, Cloyne, Cobh, Fermoy, Glanworth, Inishannon, Kinsale, Liscarroll, Midleton, Rosscarbery and Skibbereen.The project arose from a desire on the part of the Heritage Unit of Cork County Council to devise a system for managing, co‐ordinating and accessing excavation information within the county, primarily as a tool to aid the planning process. Date & Date Type 2009 – Survey Date Point of Contact Details Conor Nelligan, Heritage Unit, Cork County Council, Floor 3, County Hall, Carrigrohane Road, Cork. Phone: 021 428 5905 Email: [email protected] Theme Building, Information, Military Aspects, Research, Tourism Topic Location, Planning Cadastre, Society, Structure Online Resource http://www.corkcoco.ie/co/web/Cork%20Cou nty%20Council/Departments/Heritage /Aspects/Archaeology Data Quality Very Good Projection system used ITM Country IE County Cork Body Commissioning Survey Cork County Council Original Survey carried out by John Cronin & Associates Survey start 2009 Survey finish 2009 Updates required As resources permit Resource purpose To allow Cork County Council to devise a system for managing, co‐ordinating and accessing excavation information within the county, primarily as a tool to aid the planning process. Survey method Desk-based Survey limitations Relies on previously published reports likely to contain geographic inaccuracies Resource -potential uses Research, Planning, Historical Awareness, Education .