In This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACT Theatre Is on a Roll

Kurt Beattie Carlo Scandiuzzi Artistic Director Executive Director ACT – A Contemporary Theatre presents Opening Night September 16, 2010 Seasonal support provided by: A Contemporary Theatre Eulalie Bloedel Schneider Foundation Artists Fund The 2010 Mainstage Season is dedicated to the memory of our dear friend Buster Alvord. THE LADY WITH ALL THE ANSWERS By David Rambo Drawn from the life and letters of Ann Landers With the cooperation of Margo Howard Originally produced by The Old Globe, San Diego, California Jack O’Brien: Artistic Director Louis G. Spisto: Executive Director THE LADY WITH ALL THE ANSWERS is presented by arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc. in New York. encoreartsprograms.com A-1 WelcomE to ACT I stumbled on Ann Landers’ column one day when I was an eleven-year-old kid on Long Island, leafing through our daily TABLE OF CONTENTS Newsday. Up until then I’d never cared much about anything in the paper other than Yankee box scores, but she hooked me A-1 Title Page with a bizarre letter. A woman wrote in about how much she A-2 Welcome to ACT loved her husband, but for one alarming habit of his: when he drank martinis, his preferred cocktail, he couldn’t help taking A-3 The Company out the olives, shaking the booze off, then stuffing them up his nose. Dear Ann, what am A-4 Up Next I to do about this, the woman wanted to know. I remember laughing so hard I fell on the floor. I don’t remember Ann’s reply. I think, on occasion, she just printed a letter for her A-5 Director’s Note reader’s amusement. -

Yj*" ' 4 Dajrs for the Price Ef 3! 4 9 7 Mm Irhriitrr H Rralii

f* -r.MAWCHMTBK HKIIALP. rhanO t t , J t m 4. m i TAG SALE!!! y j*" ' 4 Dajrs for the Price ef 3! ^ PLACE YOUR AD ON TUESDAY, BEFORE NOON, AND YOU^RE ALL SET * FOR THE W EEK. JUST ASK FOR TRACEY OR IRENE IN CLASSIFIED. m m irhriitrr H rralii ) YHnr.hRSlor A City o( VillHflc flhrirni coNWiNiiMce. This a NO RAYMBNTt b td rd e m Colanlal Is Up te 3 veers. KMs your ft- loMfsd nsor thopplns, flonelai a c u itie s t oedbye, SCRANTON TAKE A LOOK tcnoels, bus lint and Aveie fereclesure. Cetch up Friday, JuriaS, 1B87 f O C f n t t rtcrtollonal artas. cMMtM.pirswni en lots poymewts such OS first OHhveiJN exsoume vneoun fermol Llvlnoonddln- Or OVOOno mOrr^OVO Or OTOII AMO setdor usee CMM~. 1986 int rooms) eovtrtd eutstoadlne credh eerd btlls. eewi see NMAMowe Oh leew front porch and o born Keep your home free end LINCOLN Blade J stylo poroot. Pricod clear without liens. Pod •rOOOOIOAfUyAN M4,PM tor Immodlott soft! credit er left payment his DAKOTA 'll.e id TOWN CAR tory Is net a problem. Kindly » Ml Jobless rate Blanchard !■ Resstfto. •7 «9TH AVI (I) <t4,2M 3 to choosp from , “Wo Ouorontoo Our colli MOObOIOAlUyAN M0,dMI Whitp/ BluP/ Brown suspected Housos". 440 asaa. o T U B IW IS S Your Cholcp Ct^AAMirJo Rustem ConsdrvBfIyp OrpuB •• 00001 nulwM M1,4M Capo. Bock on tho M IM 4 0 « P r ls n fiT H A y i.« <13,M S •• 00001 see oem. -

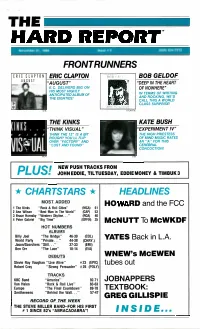

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

Durabteilung Beginn Auf 1, Eventuell Zweite Molltonika

Vier unterschiedliche Stufen Durabteilung Beginn auf 1, eventuell zweite Molltonika 1234 Parallelprogression Ärzte, Die: Himmelblau (S, G), Beatles, The: Here there and everywhere (S), Culcha Candela: Hamma! (S), Cure, The: Boys don't cry (S, R), Billy Joel: Uptown girl (S 123[45]), Juanes: La camisa negra (R), Mark Forster: Bauch und Kopf (R 123/74) 1235 (Parallelprogression), 1236 (Parallelprogression), 1243 1245 7 Years Bad Luck (Punkrock): A plain guide (to happiness) (I), Aerger (Deutschpop): Kleine Schwester (I, R) Vanessa Amorosi (Bravopop): Shine (R), Tina Arena (Cover): Show me heaven (R), Bachman Turner Overdrive: Hey you (R), Jennifer Brown: Naked (I, R), Joe Cocker: No ordinary world (R), Jude Cole: Madison (S, R), Corrs, The: All the love in the world (S), Counting Crows: Rain king (R), Nelly Furtado: In god’s hands (R), Faith Hill: Breathe (R), Gewohnheitstrinker (Punk): High Society (R), Michael Jackson: My girl (B), Jack Johnson: Upside down (R), Labrinth feat. Emeli Sandé (Reggae): Beneath your beautiful (T), Fady Maalouf (Bravopop): Blessed (Rf), Maroon 5 (Alternativepop): Won’t go home without you (R11224511), Amanda Marshall: Fall from Grace (I, S, R), Don McLean: Vincent (S), Melanie C: If that were me (S, R), Metro Station (Bravopop): Shake it (B), Alanis Morissette: Ur (T), Nena: 99 Luftballons (S, R), Laura Pausini: Il mio sbaglio più grande (I, S, R), Katy Perry: Thinking of you (R bzw. 124-4), Reamon: Josephine (I, S), Reel Big Fish (Skarock): Somebody hates me (Rf), Sell out (I, S, Z1), Savage Garden: I knew -

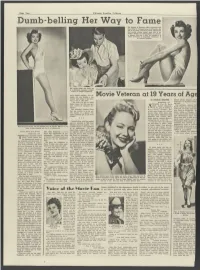

Dumb-Belling Her Way to Fame

Paje TWIG Dumb-belling Her Way to Fame The layingl of Suzanne, merry, ing.nuoUi and abounding in whimlical error, have become the talk of the Itudio, Experts in movie behaviorism and worldly willdom haven't been able to de- termine whether her malapropisms are genuine or feigned. She has "a lin.:' but whether it is native clevemell or congenital "dumbne.s" is an unsolved problem. ,......•••...... She couldn't make any sense out of (l dictionary because it wasn't written in complete sentences. way's mental capacity. For ex- Movie Veteran at 19 Years of Age ample, she was handed a dte- tionary and asked if she knew how to use it. She said: By GEORGE SHAFFER Bovard family, founders of th University of Southern Calif 01 "The book I've got at home Hollywood, Cal. nia here. makes sense, but this one isn't ALTHOUGH but 19, .Mary The actress's mother, Mr: even written in complete sen- Belch, former Blooming- I"l.. Hulda Belch, and her brothel tences." ton, Ill., girl, is already a Albert, 18, now make their hom She informed Director Prinz HoI Lyw 0 0 d "trouper." Her with Mary in Hollywood. He that she wanted to be an act- screen career began on a daring father resides in Chicago. Th ress instead of a dancer "be- chance When, three years ago, mother and brother moved rror cause actresses get to sit down the high school sophomore long their Bloomington home whe oftener." distanced Bob Palmer, RKO· Mary came west to take up he Radio studios' casting director, • • • movie career. -

Pauline Phillips, Flinty Adviser to Millions As Dear Abby, Dies at 94 - N

Pauline Phillips, Flinty Adviser to Millions as Dear Abby, Dies at 94 - N... http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/18/business/media/pauline-phillips-flin... January 17, 2013 By MARGALIT FOX Dear Abby: My wife sleeps in the raw. Then she showers, brushes her teeth and fixes our breakfast — still in the buff. We’re newlyweds and there are just the two of us, so I suppose there’s really nothing wrong with it. What do you think? — Ed Dear Ed: It’s O.K. with me. But tell her to put on an apron when she’s frying bacon. Pauline Phillips, a California housewife who nearly 60 years ago, seeking something more meaningful than mah-jongg, transformed herself into the syndicated columnist Dear Abby — and in so doing became a trusted, tart-tongued adviser to tens of millions — died on Wednesday in Minneapolis. She was 94. Her syndicate, Universal Uclick, announced her death on its Web site. Mrs. Phillips, who had been ill with Alzheimer’s disease for more than a decade, was a longtime resident of Beverly Hills, Calif., but lived in Minneapolis in recent years to be near family. If Damon Runyon and Groucho Marx had gone jointly into the advice business, their column would have read much like Dear Abby’s. With her comic and flinty yet fundamentally sympathetic voice, Mrs. Phillips helped wrestle the advice column from its weepy Victorian past into a hard-nosed 20th-century present: Dear Abby: I have always wanted to have my family history traced, but I can’t afford to spend a lot of money to do it. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

When She's Gone

When She’s Gone Steven Erikson © Steven Erikson 2004 The game got in our blood when the Selkirk Settlers first showed up at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Not hard to figure out why. They were farmers one and all and given land along the rivers, each allotment the precise dimensions of a hockey rink. Come winter the whole world froze up and there was nothing to do but skate and whack at frozen rubber discs with hickory sticks. Those first leagues were vicious. There were two major ones, the Northwest League and the Hudson's Bay League. Serious rivals and it all came to a head when Louis Riel, left-wing for the Voyageurs, jumped leagues and signed with the Métis Traders right there at the corner of Portage and Main, posing with a buffalo hide signing bonus. The whole territory went up in flames–the Riel Rebellion–culminating in the slaughter of nineteen Selkirk fans. Redcoats came from the east and refereed the mob that strung Riel up and hung him until dead. The Northwest League got merged into the Hudson's Bay League shortly afterward and a troubled peace came to the land. It was the first slapshot fired in anger, but it wouldn't be the last. The game We sold our soul. No point in complaining, no point in blaming anyone else, not the Yanks, not anyone else. We've done it ourselves and if you were a Yank you'd be saying the same thing. If your country was Italy, France or Belgium, if the city you called home was in England or Scotland or Wales, you're saying the same thing I'm saying right now, at least you'd be if you were thinking about what I'm thinking about. -

Bigamy, the French Invasion, and the Triumph of British Nationhood In

SENSATION FICTION AND THE LAW: DANGEROUS ALTERNATIVE SOCIAL TEXTS AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITAIN A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Elizabeth Godke Koonce August 2006 This dissertation entitled SENSATION FICTION AND THE LAW: DANGEROUS ALTERNATIVE SOCIAL TEXTS AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITAIN by ELIZABETH GODKE KOONCE has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Joseph P. McLaughlin Associate Professor of English Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Abstract KOONCE, ELIZABETH GODKE. Ph.D. August 2006. English SENSATION FICTION AND THE LAW: DANGEROUS ALTERNATIVE SOCIAL TEXTS AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITAIN (238 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Joseph P. McLaughlin This dissertation argues that nineteenth-century sensation fiction evoked a cultural revolution that threatened to challenge accepted norms for personal behavior and increase possibilities for scripting one’s life outside of established norms for respectable behavior. Because of the ways that it threatened to represent new scripts for personal behavior, sensation, which I term a “dangerous alternative social text,” disrupted hegemony and provided new ways of thinking amongst its Victorian British readership; it became a vehicle through which the law and government (public discourses) ended up colliding with domesticity -

CONCORD REVIEW Democracy Combined with Stagnant Economic Growth

After gaining independence from the Dutch at the conclusion of the Second World War, Indonesia found itself in a tumultuous period of Western-style parliamentary THE CONCORD REVIEW democracy combined with stagnant economic growth. During this period, a postwar THE economic boom occurred for the global timber industry beginning in the early 1950s and extending into the late 1980s. In 1959, the Philippines and Malaysia were the two largest exporters of hardwood, while Indonesia’s timber industry was still a fl edgling business.1 Indonesia, however, had an untapped forestry sector, CONCORD REVIEW with three-quarters of the entire archipelago covered in forests.2 These forests would play a pivotal role in the geopolitics of Indonesia in the ensuing decades. A longtime nationalist, President Sukarno, Indonesia’s fi rst president, created the I am simply one who loves the past and is diligent in investigating it. 1960 Basic Agrarian Law ostensibly to safeguard the Indonesian people’s basic K’ung-fu-tzu (551-479 BC) The Analects rights to the land. Article 21 paragraph one of that law stated “Only an Indonesian Yes, these are3 citizen may have rights of ownership [to forest land].” Over time, the legisla- President Suharto Jun Bin Lee tion served to push out foreign businesses from Indonesia, leaving Indonesia’s Jakarta Intercultural School, Jakarta forestry industry in tatters, as most of the sector had been composed of investors Judicial Independence Perri Wilson and corporationsHigh from abroad. Without School the support of foreign businesses, the Commonwealth School, Boston, Massachusetts growth of Indonesia’s logging operations stagnated, leaving the country with just Winter 2016 Athenian Democracy Duohao Xu $4 million in timber exports up until 1966.4 1 St. -

Tap, Tap, Click Empathy As Craft Our Cornered Culture

The Authors Guild, Inc. SPRING-SUMMER 2018 31 East 32nd Street, 7th Floor PRST STD US POSTAGE PAID New York, NY 10016 PHILADELPHIA, PA PERMIT #164 11 Tap, Tap, Click 20 Empathy as Craft 41 Our Cornered Culture Articles THE AUTHORS GUILD OFFICERS TURNING PAGES BULLETIN 5 President Annual Benefit Executive Director James Gleick An exciting season of new 8 Audiobooks Ascending Mary Rasenberger Vice President programming and initiatives is General Counsel Richard Russo underway at the Guild—including 11 Cheryl L. Davis Monique Truong Tap, Tap, Click our Regional Chapters and Editor Treasurer 16 Q&A: Representative Hakeem Jeffries Martha Fay Peter Petre enhanced author websites— 18 Making the Copyright System Work Assistant Editor Secretary on top of the services we already Nicole Vazquez Daniel Okrent offer our members. But as for Creators Copy Editors Members of the Council Heather Rodino Deirdre Bair we all know, this takes funding. 20 Empathy as Craft Hallie Einhorn Rich Benjamin So, in our seasonal Bulletin, 23 Art Direction Amy Bloom we are going to start accepting Connecting Our Members: Studio Elana Schlenker Alexander Chee The Guild Launches Regional Chapters Pat Cummings paid advertising to offset our costs Cover Art + Illustration Sylvia Day and devote greater resources Ariel Davis Matt de la Peña 24 An Author’s Guide to the New Tax Code All non-staff contributors Peter Gethers to your membership benefits. 32 American Writers Museum Wants You to the Bulletin retain Annette Gordon-Reed But our new ad policy copyright to the articles Tayari Jones is not merely for the benefit of that appear in these pages. -

Week Commencing Mon 5Th June 2017

Week commencing Mon 5th June 2017 MONDAY 5 JUNE 2017 06:00 Death on the Set (1935) Henry Kendall drama. 07:20 The Rogues (S1, Ep4) 08:20 Orders Are Orders (1954) Tony Hancock comedy. 09:55 Accident (1967) drama Dirk Bogarde. 12:00 Whats Good For The Goose (1969) Norman Wisdom comedy. 14:00 All OverThe Town (1949) drama Norman Wooland. 15:45 Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 16:00 Sea of Sand (1958) war John Gregson. 18:00 Freewheelers (S6, Ep10) 18:30 Patricia Dainton presents. 18:35 Tread Softly (1952) crime John Bentley. 20:05 A Place To Go (1964) Rita Tushingham. 21:50 Glimpses: Concord in Flight (1969) factual. 22:00 Double X (1992) crime Norman Wisdom. 00:00 Kansas City Confidential (1952) thriller Lee Van Cleef. 02:00 The Ring (1953) drama Rita Moreno. 03:40 The Big Game (1995) drama Gary Webster. 05:45 Glimpses: Furniture Craftsmen (1940) factual short. FRIDAY 9 JUNE 2017 06:00 Say It With Flowers (1934) musical drama Mary Clare. TUESDAY 6 JUNE 2017 07:20 The Rogues (S1, Ep8) 08:20 Somewhere On Leave (1943) 06:00 Flood Tide (1934) drama George Carney. 07:15 The Rogues comedy Frank Randle. 10:10 The Cowboy & the Lady (1938) drama (S1, Ep5) 08:15 Love In Pawn (1953) comedy Barbara Kelly. 09:50 Gary Cooper. 12:00 A Kid For Two Farthings (1955) fantasy Diana Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 10:05 Velvet Touch (1948) thriller Dors. 13:45 Glimpses: War & Order (1940) factual. 14:00 I’ve Gotta Rosalind Russell.