The Case for a General-Purpose Rifle and Machine Gun Cartridge (GPC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Army's M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress

The Army’s M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress Andrew Feickert Specialist in Military Ground Forces June 8, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22888 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Army’s M-4 Carbine: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The M-4 carbine is the Army’s primary individual combat weapon for infantry units. While there have been concerns raised by some about the M-4’s reliability and lethality, some studies suggest that the M-4 is performing well and is viewed favorably by users. The Army is undertaking both the M4 Carbine Improvement Program and the Individual Carbine Competition, the former to identify ways to improve the current weapon, and the latter to conduct an open competition among small arms manufacturers for a follow-on weapon. An integrated product team comprising representatives from the Infantry Center; the Armament, Research, Development, and Engineering Center; the Program Executive Office Soldier; and each of the armed services will assess proposed improvements to the M4. The proposal for the industry-wide competition is currently before the Joint Requirements Oversight Council, and with the anticipated approval, solicitation for industry submissions could begin this fall. It is expected, however, that a selection for a follow-on weapon will not occur before FY2013, and that fielding of a new weapon would take an additional three to four years. This report will be updated as events warrant. Congressional Research Service The -

Firearm Evidence

INDIANAPOLIS-MARION COUNTY FORENSIC SERVICES AGENCY Doctor Dennis J. Nicholas Institute of Forensic Science 40 SOUTH ALABAMA STREET INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA 46204 PHONE (317) 327-3670 FAX (317) 327-3607 EVIDENCE SUBMISSION GUIDELINE FIREARMS EVIDENCE INTRODUCTION Generally, crimes of violence involve the use of a firearm. The value of firearms and fired ammunition evidence will depend, to a significant degree on the recovery and submission techniques employed at the shooting event or later during autopsy. Trace evidence adhering to surfaces should be collected and submitted to the appropriate agency. This submission guideline is designed to assist you in your laboratory examination request decisions. Any situation not sufficiently explained to your specific needs may be handled on an individual basis by contacting the laboratory at (317) 327-3670 or the Firearms Section Supervisor at (317) 327-3777. A. The following is a list of items most commonly submitted to the Firearms Section for analyses: 1. Firearms 2. Cartridge Cases 3. Cartridges 4. Fired Bullets / Fragments 5. Shotshells 6. Wads 7. Slug / Pellets 8. Victim’s Clothing B. The I-MCFSA Firearms Section can conduct the following analysis: 1. Examination of firearms for function and safety, including test firing in order to obtain test bullets, cartridge cases and shot shells. 2. Comparison of evidence bullets, fired cartridge cases and shot shells to determine if they were or were not fired by the same firearm or the submitted firearm. 3. Examination of fired bullets to potentially determine caliber and possible make and type of firearm involved. 4. Imaging and comparing fired cartridge cases and test shots from firearms to similar exhibits recovered in unsolved crimes utilizing the NIBIN system (see NIBIN Submission Guideline #14). -

Guns Dictionary : Page K1 the Directory: K–Kynoid

GUNS DICTIONARY : PAGE K1 THE DIRECTORY: K–KYNOID Last update: May 2018 k Found on small arms components made in Germany during the Second World War by →Luck & Wagner of Suhl. K, crowned. A mark found on Norwegian military firearms made by→ Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk. K, encircled. Found on miniature revolvers made in the U.S.A. prior to 1910 by Henry M. →Kolb. Kaba, KaBa, Ka-Ba, KA-BA Marks associated with a distributor of guns and ammunition, Karl →Bauer of Berlin. Bauer imported 6·35mm →Browning- type pocket pistols from Spain, and sold ‘KaBa Special’ patterns which seem to have been the work of August →Menz. Kaba Spezial A Browning-type 6·35mm automatic pistol made in Spain by Francisco →Arizmendi of Eibar for Karl →Bauer of Berlin. Six rounds, striker fired. Kabakov Yevgeniy Kabakov was co-designer with Irinarkh →Komaritskiy of the sight-hood bayonet issued with the perfected or 1930-pattern Soviet →Mosin Nagant rifle. Kabler William or Wilhelm Kabler of Sante Fé, Bracken County, Kentucky, traded as a gunmaker in the years immediately before the Civil War. Kacer Martin V. Kacer of St Louis, Missouri, was the co-grantee with William J. Kriz of U.S. Patents 273288 of 6th March 1883 (‘Fire-Arm’, application filed on 16th January 1882) and 282328 of 31st July 1883 (‘Magazine Fire- Arm’, application filed on 7th December 1882). These patents protected, respectively, a break-open double barrel gun and a lever-action magazine rifle with a magazine in the butt-wrist. Kadet, Kadet Army Gun: see ‘King Kadet’. Kaduna arms factory The principal Nigerian manufacturory, responsible for local adaptations to →Garand and FN →FAL rifles. -

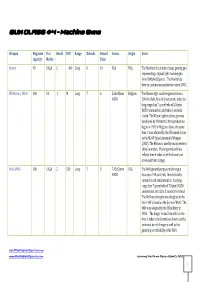

Machine Guns

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

Download Enemy-Threat-Weapons

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS THE BASIC SCHOOL MARINE CORPS TRAINING COMMAND CAMP BARRETT, VIRGINIA 22134-5019 ENEMY THREAT WEAPONS B2A2177 STUDENT HANDOUT/SELF PACED INSTRUCTION Basic Officer Course B2A2177 Enemy Threat Weapons Enemy Threat Weapons Introduction In 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. The Soviets assumed this would be a short uneventful battle; however, the Mujahadeen had other plans. The Mujahadeen are guardians of the Afghani way of live and territory. The Soviets went into Afghanistan with the latest weapons to include the AK-74, AKS-74, and AKSU-74, which replaced the venerable AK-47 in the Soviet Arsenals. The Mujahadeen were armed with Soviet-made AK-47s. This twist of fate would prove to be fatal to the Soviets. For nearly 11 years, the Mujahadeen repelled the Soviet attacks with Soviet-made weapons. The Mujahadeen also captured many newer Soviet small arms, which augmented their supplies of weaponry. In 1989, the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan back to the other side of the mountain. The Mujahadeen thwarted a communist take- over with their strong will to resist and the AK-47. This is important to you because it illustrates what an effective weapon the AK-47 is, and in the hands of a well-trained rifleman, what can be accomplished. Importance This is important to you as a Marine because there is not a battlefield or conflict that you will be deployed to, where you will not find a Kalashnikov AK-47 or variant. In This Lesson This lesson will cover history, evolution, description, and characteristics of foreign weapons. -

Adcor and the Demise of the Improved Carbine Competition

Adcor and the Demise of the Improved Carbine Competition 5/09/13 | by Max Slowik After five years of trials, the U.S. Army announced plans to cancel the Improved Carbine Competition on the heels of the end of its second phase. The competition would evaluate a handful of rifles that were in contention to replace the M4; the Colt ACC-M (sometimes called the ACM), the FN FNAC, the Heckler & Koch HK416, the Remington ACR and one by the upstart rifle manufacturer Adcor Defense, the BEAR Elite. In an attempt to tighten their budget, the Army has made the decision to halt the competition, saving them as much as $300 million from now through 2018. Right of the bat the Army will save $49 million in 2014, the first year of individual carbine field testing. The Army originally planned to put 30,000 rifles into service for further evaluation. Of the five rifles that were selected for phase II of the trials, three were to be put to the test in phase III. The Army is cancelling the competition before announcing which three rifles would make it to the final stage of testing, six weeks after the Inspector General audited the program. As the Army is currently in phase I of the M4 Product Improvement Program, upgrading their current M4s to M4A1s and exploring options for phase II, replacing the standard carbine handguard with a free-floating quad rail, the auditors decided that the Army doesn’t need a new rifle to replace the current crop of M4s. Phase III of the competition would have determined if these newer rifles would outperform the M4 in terms of reliability, accuracy and barrel life. -

![219 Zipper [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5970/219-zipper-pdf-425970.webp)

219 Zipper [PDF]

219 ZIPPER .365 12° .253 .506 .422 .252 .063 1.359 1.621 1.938 219 ZIPPER RIFLE: . F.N. Mauser Custom BULLET DIAMETER:. 0.224" BARREL: . 27", 1 in 14" Twist MAXIMUM C.O.L.: . 2.260" CASE: . Remington MAX. CASE LENGTH: . 1.938" PRIMER: . Federal 210 CASE TRIM LENGTH: . 1.928" Winchester introduced the 219 Zipper in 1937, seven years after the Hornet and two years after the powerful 220 Swift. Chambered in the fi rm’s Model 64 lever action varmint version of the famous Model 94, it never delivered the tack-driving accuracy customers demanded and consequently never became widely popular. Winchester discontinued manufacturing the Model 64 after WW II and the 219 Zipper became an orphan in 1961 when Marlin stopped chambering its Model 336 for the cartridge. The Zipper is now completely a handloading proposition since both Remington and Winchester have discontinued producing ammunition. A necked down 25-35 WCF (which can also be formed from 30-30 brass), the 219 Zipper was and is a respectable performer. Top velocities possible for the cartridge are only 100 fps lower than those which can be developed in the 224 Weatherby Varmintmaster. The Hornady 53 grain V-MAX™ or the 55 grain Spire Point are fi ne choices for the 219 Zipper and the cartridge is large enough to propel the wind-bucking 60 grain SP or HP up to an impressive 3300 fps. H 4895 is a very good powder throughout the entire range of available bullet weights and especially with the heavier selections. Hornady 22 caliber V-MAX™ bullets are extra potent in the Zipper. -

Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (Part 1)

NONFERROUSNONFERROUS HEATHEAT TREATING TREATING Rimfire Firing-Pin Indent Copper Crusher (part 1) Daniel H. Herring – The HERRING GROUP, Inc.; Elmhurst, Ill. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute Inc., also known as SAAMI, is an association of the nation’s leading manufacturers of rearms, ammunition and components. SAAMI is the American National Standards Institute-accredited standards Fig. 1. Firing-pin indent copper crushers developer for the commercial small arms and ammunition industry. SAAMI was for 22-caliber rimfire ammunition founded in 1926 at the request of the federal government and tasked with: creating and (courtesy of Cox Manufacturing and publishing industry standards for safety, interchangeability, reliability and quality; and Kirby & Associates) coordinating technical data to promote safe and responsible rearms use. he story of SAAMI’s rimfire firing-pin indent copper pressures and increased bullet velocities. crusher describes the reinvention of one of the most The primary advantage of rimfire ammunition is low cost, important tools in the ammunition and firearms industry typically one-fourth that of center fire. It is less expensive to T(Fig. 1). This article explains the purpose and operation manufacture a thin-walled casing with an integral-rimmed of the rimfire firing-pin indent copper crusher and how an primer than it is to seat a separate primer in the center of the unusual chain of events almost led to the disappearance of this head of the casing. simple but important technology. The most common rimfire ammunition is the 22LR (22-caliber long rif le). It is considered the most popular round Rimfire Ammunition in the world and is commonly used for target shooting, small- In order to discuss the rimfire copper crusher, we need to take a game hunting, competitive rifle shooting and, to a lesser extent, step back and first explain what rimfire ammunition is and how it works. -

American Army

ASSAULT PLATOON AMERICAN ARMY MASSIMO TORRIANI – VALENTINO DEL CASTELLO - Copyright 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, including mechanical and/or electronic methods, without the author’s prior written permission. For updates: www.torrianimassimo.it Version December 2013 1 AMERICAN ARMY (1943-1945) BASIC INFANTRY PLATOON The Platoon comprises: 0-1 Infantry HQ Squad (180 points), 2-3 Infantry Squads (370 points each) INFANTRY HQ SQUAD Infantry Unit, HQ Breakpoint: 2 TV: 3 No. Model Weapon Characteristics M1 semi-automatic carbine, Colt 1911A1 pistol, MKII 1 Lieutenant HQ leader Pineapple grenades 1 Second Lieutenant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades HQ leader 1 Sergeant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades HQ leader 2 Riflemen Garand M1 semi-automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades INFANTRY SQUAD Infantry Unit Breakpoint: 5 TV: 3 No. Model Weapon Characteristics 1 Sergeant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades leader 1 Corporal M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades leader 1 Machine-gunner BAR M1918A2 automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades 9 Riflemen Garand M1 semi-automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades SPLITTING UP AN INFANTRY SQUAD Each Infantry Squad can be split up into two Sections: the first comprising a Sergeant and 6 Riflemen (BRK 3) and the other comprising the Corporal, the Machine-gunner and 3 Riflemen (BRK 2). VARIANTS: You can add a radio to the HQ Squad for +10 points. One of the riflemen in the Squad gets the radio characteristic. Leaders can replace their M1 semi-automatic carbines with M3A1 Grease Gun sub-machine guns for free. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

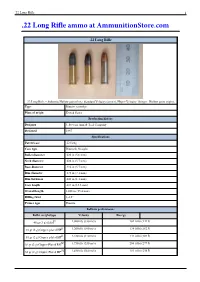

22 Long Rifle Ammo at Ammunitionstore.Com

.22 Long Rifle 1 .22 Long Rifle ammo at AmmunitionStore.com .22 Long Rifle .22 Long Rifle – Subsonic Hollow point (left). Standard Velocity (center), Hyper-Velocity "Stinger" Hollow point (right). Type Rimfire cartridge Place of origin United States Production history Designer J. Stevens Arm & Tool Company Designed 1887 Specifications Parent case .22 Long Case type Rimmed, Straight Bullet diameter .222 in (5.6 mm) Neck diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Base diameter .226 in (5.7 mm) Rim diameter .278 in (7.1 mm) Rim thickness .043 in (1.1 mm) Case length .613 in (15.6 mm) Overall length 1.000 in (25.4 mm) Rifling twist 1–16" Primer type Rimfire Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy [] 40 gr (3 g) Solid 1,080 ft/s (330 m/s) 104 ft·lbf (141 J) [] 38 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,260 ft/s (380 m/s) 134 ft·lbf (182 J) [] 31 gr (2 g) Copper-plated HP 1,430 ft/s (440 m/s) 141 ft·lbf (191 J) [1] 30 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated RN 1,750 ft/s (530 m/s) 204 ft·lbf (277 J) [1] 32 gr (2 g) Copper-Plated HP 1,640 ft/s (500 m/s) 191 ft·lbf (259 J) .22 Long Rifle 2 [][1] Source(s): The .22 Long Rifle rimfire (5.6×15R – metric designation) cartridge is a long established variety of ammunition, and in terms of units sold is still by far the most common in the world today. The cartridge is often referred to simply as .22 LR ("twenty-two-/ˈɛl/-/ˈɑr/") and various rifles, pistols, revolvers, and even some smoothbore shotguns have been manufactured in this caliber. -

30-06 Springfield 1 .30-06 Springfield

.30-06 Springfield 1 .30-06 Springfield .30-06 Springfield .30-06 Springfield cartridge with soft tip Type Rifle Place of origin United States Service history In service 1906–present Used by USA and others Wars World War I, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, to present Production history Designer United States Military Designed 1906 Produced 1906–present Specifications Parent case .30-03 Springfield Case type Rimless, bottleneck Bullet diameter .308 in (7.8 mm) Neck diameter .340 in (8.6 mm) Shoulder diameter .441 in (11.2 mm) Base diameter .471 in (12.0 mm) Rim diameter .473 in (12.0 mm) Rim thickness .049 in (1.2 mm) Case length 2.494 in (63.3 mm) Overall length 3.34 in (85 mm) Case capacity 68 gr H O (4.4 cm3) 2 Rifling twist 1-10 in. Primer type Large Rifle Maximum pressure 60,200 psi Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy 150 gr (10 g) Nosler Ballistic Tip 2,910 ft/s (890 m/s) 2,820 ft·lbf (3,820 J) 165 gr (11 g) BTSP 2,800 ft/s (850 m/s) 2,872 ft·lbf (3,894 J) 180 gr (12 g) Core-Lokt Soft Point 2,700 ft/s (820 m/s) 2,913 ft·lbf (3,949 J) 200 gr (13 g) Partition 2,569 ft/s (783 m/s) 2,932 ft·lbf (3,975 J) 220 gr (14 g) RN 2,500 ft/s (760 m/s) 2,981 ft·lbf (4,042 J) .30-06 Springfield 2 Test barrel length: 24 inch 60 cm [] [] Source(s): Federal Cartridge / Accurate Powder The .30-06 Springfield cartridge (pronounced "thirty-aught-six" or "thirty-oh-six"),7.62×63mm in metric notation, and "30 Gov't 06" by Winchester[1] was introduced to the United States Army in 1906 and standardized, and was in use until the 1960s and early 1970s.