War, Genocide, and Resistance in East Timor, 1975–99: Comparative Reflections on Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambodia Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report #2 13 July 2020 Report As of 13 July 2020, 11:30 Am ICT

Cambodia Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report #2 13 July 2020 Report as of 13 July 2020, 11:30 am ICT Situation Summary Highlights of Current Situation Report • As of 13 July 2020, 156 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported from Cambodia to WHO, of which 133 have recovered. 118 cases were acquired overseas, representing 10 nationalities in addition to Cambodian, with the rest locally acquired. Eight patients are currently being treated in Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital and 15 at Chakangre Health Centre, both in Phnom Penh. • 79 contacts are being monitored daily over 14 days for possible development of symptoms through automatic voice calls using the 115 hotline system. • The 15 most recent cases identified on 12 July are Cambodian men between the ages of 21 and 33, who travelled from Saudi Arabia and were detected as a result of extensive airport screening measures for all incoming passengers. • Points of Entry measures are currently being strictly implemented including testing on arrival and 14-day quarantine for all airport passengers and at border crossings. • Joint high-level field missions, led by the Secretary of State, Ministry of Health (MOH) and the WHO Representative, have been undertaken to the north eastern and to the north western regions (total 7 provinces) to assess and advise on strengthening provincial-level preparedness and response. Upcoming Events and Priorities • On 15 July, the Ministry of the Interior will host a high-level meeting between the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) key institutions and the UN Country Team (UNCT) on the joint programme to support returning migrants during COVID-19. -

Judging the East Timor Dispute: Self-Determination at the International Court of Justice, 17 Hastings Int'l & Comp

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 17 Article 3 Number 2 Winter 1994 1-1-1994 Judging the East Timor Dispute: Self- Determination at the International Court of Justice Gerry J. Simpson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Gerry J. Simpson, Judging the East Timor Dispute: Self-Determination at the International Court of Justice, 17 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 323 (1994). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol17/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judging the East Timor Dispute: Self-Determination at the International Court of Justice By Gerry J. Simpson* Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................ 324 1E. Some Preliminary Remarks about the Case ............. 327 III. International Politics and the International Court: A Functional Dilemma .................................... 329 IV. Substantive Questions of Law .......................... 332 A. The Existence of a Right to Self-Determination...... 333 B. Beneficiaries of the Right to Self-Determination ..... 334 1. Indonesia's TerritorialIntegrity and the Principle of Uti Posseditis................................. 339 2. Enclaves in InternationalLaw .................. 342 3. Historical Ties .................................. 342 C. The Duties of Third Parties Toward Peoples Claiming a Right to Self-Determination ............. 343 V. Conclusion .............................................. 347 * Lecturer in International Law and Human Rights Law, Law Faculty, Univcrity of Melbourne, Australia. -

How the Resource Curse Affects Urban Development in East Timor

The Sustainable City V 495 How the resource curse affects urban development in East Timor I. M. Madaleno Portuguese Tropical Research Institute, Lisbon Abstract East Timor is heavily reliant upon royalty and taxation revenues from petroleum and natural gas resources. Poor management of natural resources revenue has given ground for the nation to fall victim to the ‘resource curse’. This paper provides an overview of the country’s recent history whilst characterising its energy resources availability and case-studying a stressing and omnipresent urban problem: the persistence of internal displaced people (idps) living in refugee camps within Dili district. The objective of this contribution is to describe sample research conducted in the capital city of the first 21st century nation on Earth, so as to evaluate with empirical data how the wealth of natural resources is being used both to improve East Timorese daily lives and to regenerate the urban tissue. Keywords: resource curse, refugee camps, urban regeneration, Dili, East Timor. 1 Introduction Asian tigers – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong-Kong and Singapore – are resource- poor countries. East Timor as well as Angola, both former Portuguese colonies, are resource-rich, exhibiting poor economic growth performances and displaying high levels of poverty (see table 1). The quality of local institutions is decisive, though, for there is no curse that cannot be lifted [1, 2]. It is widely accepted that good governance and a strong juridical and institutional framework tend to minimise the ill consequences of the mineral and energy resources privilege both on common people and on political leaders. Weak administration of revenues by contrast can lead to financial resources waste and environmental constrains on grounds of political mismanagement and corruption as on easy money availability excesses. -

Responsibility and Accountability

Part 8: Responsibility and Accountability Part 8: Responsibility and Accountability ..............................................................................................1 Part 8: Responsibility and Accountability ..............................................................................................2 8.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................2 8.2 Principal findings..........................................................................................................................5 8.3 Methodology for identification of institutional responsibility.....................................................11 8.4 Responsibility and accountability of the Indonesian security forces .......................................15 High-level responsibility........................................................................................................................51 The scale of violations:.........................................................................................................................52 The pattern of violations.......................................................................................................................52 Strategy.................................................................................................................................................52 Institutional norms and culture.............................................................................................................53 -

The Indonesian Who Joined Falintil'

The Indonesian who Joined Falintil' Preface, by Gerry van Klinken The Indonesian who joined Falintil, like the American who joined A1 Qaeda or the Dutchman who joined the 1945 Indonesian revolutionaries, has power to shock because such a person questions the fundamental categories of the conflict. What after all is an Indonesian, an American, or a militant Muslim? What is this contest about? Muhammad Nasir crosses boundaries most see as so natural they are insuperable. He transforms himself from the street kid, Ketut Narto, to the policeman's adopted kid, Muhammad Nasir, and from there to the "oddball" guerrilla Klik Mesak (and presumably from Hindu to Muslim to whatever) and travels from Bah to Comandante Ular's Region 4 headquarters in the mountains of East Timor. For Nasir, these boundaries have little power to exclude. All the communities they enclose have a claim on him, but none more than others. Meanwhile, other boundaries do have authority for him. The eloquence with which this high school dropout describes the boundaries of "rights" is striking. Taking what he needs from a bankrupt school system, he discovers truths in history text books their authors never intended him to find: East Timor, being Portuguese, wasn't available for the taking by the former Dutch colony of Indonesia. The camaraderie of the school yard in Baucau and Dili does not distinguish between names. But here Nasir discovers the rights of "we" locals. "I wouldn't want anyone to take away my rights." The real divide is not between Indonesian and East Timorese, let alone between Muslim and Hindu or Catholic. -

Walking in Hato Builico Timor Leste

Blue Mountains East Timor Friendship Committee The Friendship Committee was formed in 2006 as part of an Australia-wide initiative to develop friendship agreements with communities in Timor-Leste. To date, more than 40 councils across Australia have participated. Walking in Hato Builico The Blue Mountains committee is made up of community members, councillors and council staff from Blue Mountains City Council, all committed to improving the lives of the rural community of Hato Builico. A partner committee of residents of Hato Timor Leste Builico assesses the needs of the community and liaises with the Blue Mountains to progress projects. Fundraising events are organised regularly by volunteers. If you live in or plan to visit Australia in 2012, what about raising funds for Hato Builico by joining the sponsored Trek for Timor Blue Mountains on September 15th 2012. 50km or 15km - the choice is yours. www.trekfortimorbm.org.au Members of the Blue Mountains committee visit regularly on self-funded trips to monitor progress of projects and to talk to villagers about their needs. In 2011, a volunteer from Australian Volunteers International will spend extended periods in Hato Builico to work on local projects. Projects so far have included: Refurbishment of a community centre for training and community meetings Scholarships for 43 students to attend primary school, high school and university Collaborations between schools in East Timor and Blue Mountains Hedge seedlings to counteract the effects of deforestation Solar panels for the community centre Two water tanks for the community centre (supported by Rotary) Sports equipment, school equipment, readers and guitars for schools as well as participation in training for sports teaching And of course – this project! Two volunteers from the Blue Mountains spent three months living in Hato Builico and developing this series of guided walks. -

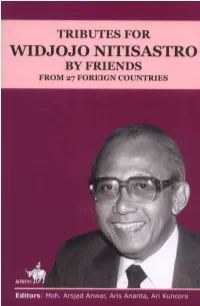

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA Mestrado Em Ciências Da Terra, Da

UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA ESCOLA DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA Mestrado em Ciências da Terra, da Atmosfera e do Espaço Especialização em Processos Geológicos Dissertação Caracterização dos movimentos de massa no distrito de Baucau (Zona Oeste) Autor Félix Januário Guterres Jones Orientador: Pedro Miguel Nogueira Co-Orientador: Domingos Manuel Rodrigues Dezembro de 2011 AGRADECIMENTOS Este trabalho foi elaborado no âmbito da dissertação de mestrado para obtenção do grau de mestre em geologia, numa cooperação entre a Secertado de Estado de Recurso Naturais Universidade de Èvora e o, a estas direção o meu agradecimento. Desejo expressar também os meus agradecimentos a algumas pessoas sem as quais não seria possível a realização deste trabalho. · Orientador Professor Doutor Pedro Nogueira pela orientação, sugestões e apoio dado na resolução de dúvidas que foram surgiram ao longo da realização deste trabalho; · Ao meu co-orientador Doutor Domingos Rodrigues (Universidade de Madeira), pelo apoio e orientação que me deu durante a realização do mesmo, pela sua objectividade, pelas sugestões dadas e indicação de caminhos no sentido de resolver os problemas e questões que urgiram; Aos meus colegas Apolinario Euzebio Alver agradeço pela ajuda no trabalho de campo. Agradece Professor Doutor Rui Dias Agradece Professor Doutor Alexander Araujo Agradece Professor Doutor Luis Lopes Agradece Professor Paula Faria pela ajuda prática labotorio Agradece Sr. Antonio Soares diração Meteórologia pela suporta dados de precipitação e diração Algis no Minesterio de Agricultura e Pescas Agradece Sr. Antonio Aparicio Guterres Administrador de Baucau, Policia distrito de Baucau, Sub-Distrito Agradece tambam Administrador Sub-Distrito Baucau, Venilale, Vemasse Agradece Chefi de Suco e Chefi de Aldeia na zona de trabalho Agradece nossa Guia pela ajudamos na zona de pesquisa Agradece Sr. -

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: a Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System

Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: John O. Haley, Chair Michael E. Townsend Beth E. Rivin Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Law © Copyright 2015 Yu Un Oppusunggu ii University of Washington Abstract Sudargo Gautama and the Development of Indonesian Public Order: A Study on the Application of Public Order Doctrine in a Pluralistic Legal System Yu Un Oppusunggu Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor John O. Haley School of Law A sweeping proviso that protects basic or fundamental interests of a legal system is known in various names – ordre public, public policy, public order, government’s interest or Vorbehaltklausel. This study focuses on the concept of Indonesian public order in private international law. It argues that Indonesia has extraordinary layers of pluralism with respect to its people, statehood and law. Indonesian history is filled with the pursuit of nationhood while protecting diversity. The legal system has been the unifying instrument for the nation. However the selected cases on public order show that the legal system still lacks in coherence. Indonesian courts have treated public order argument inconsistently. A prima facie observation may find Indonesian public order unintelligible, and the courts have gained notoriety for it. This study proposes a different perspective. It sees public order in light of Indonesia’s legal pluralism and the stages of legal development. -

Applying the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: a Case Study of Henry Kissinger

Applying the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Case Study of Henry Kissinger Steven Feldsteint TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................... 1665 I. Background ........... ....... ..................... 1671 A . H enry Kissinger ........................................................................ 1672 B. The Development of International Humanitarian Law ............. 1675 1. Sources of International Law ............................................. 1676 2. Historical Development of International Humanitarian L aw ..................................................................................... 16 7 7 3. Post-World War 11 Efforts to Codify International Hum anitarian Principles ................................................. 1680 a. The 1948 Genocide Convention ......................................... 1680 b. The Geneva Conventions ................................................... 1682 c. United Nations Suite of Human Rights Conventions ......... 1684 C. The Development of International War Crimes Tribunals ....... 1685 1. N urem berg Tribunal ........................................................... 1685 2. IC TY and IC TR .................................................................. 1687 3. The International Criminal Court ....................................... 1688 4. U niversal Jurisdiction ......................................................... 1694 5. A lien Tort Claim s A ct ........................................................ 1695 I1. Individual Accountability -

Peace in Timor-Leste

2. A Brief History of Timor Knowledge of the ancient indigenous history of the island of Timor is limited. Prior to colonisation, Timor was divided into dozens of small kingdoms ruled by traditional kings called liuri. They were reliant on slash-and-burn agriculture. The Dawan or Atoni, who might have been the earliest settlers of the islands from mainland Asia, came to occupy the 16 local kingdoms (reinos) in the west of Portuguese Timor at the time of colonisation. The Belu or Tetun migrated to Timor in the fourteenth century, creating 46 tiny kingdoms in the east of the island by pushing the Dawan to the west (Fox 2004; Therik 2004:xvi). Perhaps as early as the seventh century, Chinese and Javanese traders were visiting Timor with an interest in the plentiful sandalwood on the island. This was the same resource that attracted the Portuguese a millennium later, as well as trade in Timorese slaves (Kammen 2003:73). Coffee was introduced as a significant export after 1815. The Chinese, Javanese and later the Portuguese continued as the dominant international influences in Timorese history. James Dunn (2003:9) reports that ethnic Chinese dominance of commerce was formidable in East Timor prior to the Indonesian invasion: ‘In the early 1960s, of the 400 or so wholesale and retail enterprises in the Portuguese colony all but three or four were in Chinese hands. The latter were controlled not by Timorese but by Portuguese.’ The Chinese, on Nicol’s (2002:44) estimate, controlled 95 per cent of all business in East Timor in April 1974. -

Huanglongbing in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar

Fourteenth IOCV Conference, 2000—Short Communications Huanglongbing in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar M. Garnier and J. M. Bové ABSTRACT. Surveys conducted in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar have shown that several citrus species were showing HLB-like symptoms. PCR analysis of leaf midrib samples indicated that “Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus” infects various citrus cultivars in all the sites visited. Diaphorina citri, the Asian psyllid vector of HLB, was also seen in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. Huanglongbing (HLB) has been and in Laos in 1997. The samples shown previously to be present in were brought back to Bordeaux and several south and south-east Asian tested by DNA/DNA hybridization countries, namely Bangladesh, (4) for the samples from Cambodia India, China, Vietnam, Thailand, and by PCR with primers OI1/OI2C/ and Malaysia (1) We have now OA1 (2, 3) for the samples from Laos obtained evidence for the occurrence and Myanmar. Examples of the PCR of HLB in three additional countries results are shown on Fig. 1 (top) for in South East (SE) Asia. Collection Myanmar samples. PCR results are of citrus leaf samples showing HLB- presented on Tables 1 and 2. Pum- like symptoms such as mottle were melo near Phnom Penh and Siem carried out in Cambodia in 1995, in Reap in Cambodia were found posi- Myanmar (formerly Burma) in 1996 tive by DNA/DNA hybridization TABLE 1 PCR-DETECTION OF “CANDIDATUS LIBERIBACTER ASIATICUS” IN MYANMAR Region Cultivar Sample Number PCR MANDALAY Moemeik Lime 1 + Myitngde Lime 2 2+ KALAW Mandarin seedling 3 2+ PINDAYA/ZAYDAN Mandarin/RL 4 3+ “ Rough lemon 5 2+ “Lime62+ “ Mandarin 7 3+ “ Mandarin 8 2+ “ Mandarin 9 + AUNGBAN Navel 10 + “11+ “12— INLE Kyasar Rough lemon 13 3+ “ Mandarin 14 3+ Inle Lime 15 3+ PEGU/SARLAY Pummelo 16 — “ Pummelo 17 + “Lime183+ 378 Fourteenth IOCV Conference, 2000—Short Communications 379 Fig.