Visual Novel and Its Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Novel Game Critical Hit Free Download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam

visual novel game critical hit free download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. From mind-blowing twists to heartwarming stories, we’ve got you covered. Home » Galleries » Features » Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. Visual Novels are one of the oldest genres around for gaming. As such, there’s been a ton of them. While they’ve largely kept to PC, they do sometimes dive into the console world. But there’s no denying that the best visual novels can be found on PC and – more specifically – Steam. Here they are, hand-picked by us for you. Here are the best visual novels of all time, available for you to download on PC and steam. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Umineko (When They Cry) – Umineko is a visual novel in the truest sense of the term. Meaning there’s no gameplay to speak of at all; the entire ‘game’ is just a matter of clicking through copious amounts of text and watching as the story unfold. Despite the sluggish start to the first three episodes, things pick up dramatically once the creepy stuff kicks in, and Umineko stands tall as one of the most intriguing and engaging visual novel stories we’ve ever played. That soundtrack too, though. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Higurashi (When They Cry) – Higurashi is a predecessor of sorts to Umineko, and while its story is just as gripping, we don’t recommend starting with this one unless you enjoyed what you saw of Umineko. -

The Visual Arts Blueprint

The Visual Arts Blueprint A workforce development plan for the visual arts in the UK November 2009 Creative & Cultural Skills is the Sector Skills Council for Advertising, Craft, Cultural Heritage, Design, Performing Arts, Music, Visual Arts and Literature. There are 25 Sector Skills Councils in total, established in 2005 as independent employer- led UK-wide organisations governed by the UK Commission for Employment and Skills. Creative & Cultural Skills exists to bridge the gap between industry, education and the Government to give employers real influence over education and skills in the UK. Creative & Cultural Skills’ vision is to make the UK the world’s creative hub. Creative & Cultural Skills’ mission is to turn talent into productive skills and jobs, by: • Campaigning for a more diverse sector and raising employer ambition for skills • Helping to better inform the career choices people make • Ensuring qualifications meet real employment needs • Developing skills solutions that up-skill the workforce • Underpinning all this work with high quality industry intelligence The Visual Arts Blueprint is part of the Creative Blueprint, Creative & Cultural Skills’ Sector Skills Agreement with the UK Commission for Employment and Skills. The Creative Blueprint for England, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales is available at www.ccskills.org.uk. Creative & Cultural Skills has produced this Visual Arts Blueprint in partnership with Arts Council England. Arts Council England works to get great art to everyone by championing, developing and investing in artistic experiences that enrich people’s lives. As the national development agency for the arts, Arts Council England supports a range of artistic activities from theatre to music, literature to dance, photography to digital art, carnival to crafts. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Gaming Introduction/Schedule ...........................................4 Role Playing Games (Campaign) ........................................25 Board Gaming ......................................................................7 Campaign RPGs Grid ..........................................................48 Collectible Card Games (CCG) .............................................9 Role Playing Games (Non-Campaign) ................................35 LAN Gaming (LAN) .............................................................18 Non-Campaign RPGs Grid ..................................................50 Live Action Role Playing (LARP) .........................................19 Table Top Gaming (GAME) .................................................52 NDMG/War College (NDM) ...............................................55 Video Game Programming (VGT) ......................................57 Miniatures .........................................................................20 Maps ..................................................................................61 LOCATIONS Gaming Registration (And Help!) ..................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd Floor, South Hall Artemis Spaceship Bridge Simulator ..........................................................................................Westin, 14th Floor, Ansley 7/8 Board Games ................................................................................................... AmericasMart Building 1, 2nd -

Fault Milestone One Downloadl

Fault - Milestone One Download]l 1 / 4 Fault - Milestone One Download]l 2 / 4 3 / 4 ... up to 6 high volume, near fault tolerant, store and processing systems designed for both the ... Only one (l) solicitation package will be provided to each individual requestor ... He entire solicitation will be available at the site for viewing or downloading ... Production area, assumed 100 km (62 mile) radius of zero milestone, .... Fortnite Eon Cosmetic Set + 2000 V- Bucks Pack - Xbox One Download Code. ... keep) Fallen Enchantress fault - milestone two side:above fault milestone one. ... ÁÝÝ rï}ï»óî[o¾ fý³fzí>»wuuuWUWwÕé½É DÄh éX È6·&f ` ™˜‰ ˆl - xxèeÌm€ æ .... Fault Milestone Two : All the news and reviews on Qwant Games - Fault%20Milestone%20Two%20is%20a% ... Fault Milestone One Full Game Download !. GET DIGITAL E-DELIVERY. Why wait? Get digital delivery. Activate your purchase online! INDIA's LARGEST STORE FOR GAMING & E-GOODS. 15,000+ Digital .... fault - milestone one. | # | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |. Album name: fault - milestone one. Suivez l'histoire d'une princesse prénommée Selphine et de sa gardienne royale, Ritona. Quand une attaque soudaine ravage leur terre .... fault - milestone one Steam Key Digital Download PC [Global]. £1.99 Free postage. Est. delivery Wed, 26 Feb - Fri, 6 Mar. Long-time member. More than 49% .... fault is a series of Science Fantasy Cinematic Novels using a unique 3D Camera system for a visually immersive reading experience. Follow ... Download Demo. Single- .. -

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games

Mukokuseki and the Narrative Mechanics in Japanese Games Hiloko Kato and René Bauer “In fact the whole of Japan is a pure invention. There is no such country, there are no such peo- ple.”1 “I do realize there’s a cultural difference be- tween what Japanese people think and what the rest of the world thinks.”2 “I just want the same damn game Japan gets to play, translated into English!”3 Space Invaders, Frogger, Pac-Man, Super Mario Bros., Final Fantasy, Street Fighter, Sonic The Hedgehog, Pokémon, Harvest Moon, Resident Evil, Silent Hill, Metal Gear Solid, Zelda, Katamari, Okami, Hatoful Boyfriend, Dark Souls, The Last Guardian, Sekiro. As this very small collection shows, Japanese arcade and video games cover the whole range of possible design and gameplay styles and define a unique way of narrating stories. Many titles are very successful and renowned, but even though they are an integral part of Western gaming culture, they still retain a certain otherness. This article explores the uniqueness of video games made in Japan in terms of their narrative mechanics. For this purpose, we will draw on a strategy which defines Japanese culture: mukokuseki (borderless, without a nation) is a concept that can be interpreted either as Japanese commod- ities erasing all cultural characteristics (“Mario does not invoke the image of Ja- 1 Wilde (2007 [1891]: 493). 2 Takahashi Tetsuya (Monolith Soft CEO) in Schreier (2017). 3 Funtime Happysnacks in Brian (@NE_Brian) (2017), our emphasis. 114 | Hiloko Kato and René Bauer pan” [Iwabuchi 2002: 94])4, or as a special way of mixing together elements of cultural origins, creating something that is new, but also hybrid and even ambig- uous. -

Official Playstation Magazine! Get Your Copy of the Game We Called A, “Return to Form for the Legendary Spookster,” in OPM #108 When You Subscribe

ISSUE 114 OCTOBER 2015 £5.99 gamesradar.com/opm LARA COMES HOME TOMB RAIDER It’s official! First look as Rise Of The Tomb Raider heads to PS4 ASSASSIN’SBETTER ON PS4! CREED SYNDICATE Back to its best? Victorian London explored and PS4-exclusive missions uncovered in our huge playtest EXPERT PLAYTEST STAR WARS BATTLEFRONT Fly the Millennium Falcon in the mode of your dreams COMPLETED! RECORD-BREAKING TEN-PAGE METAL GEAR SOLID REVIEW DESTINY: MAFIA III COMES BACK FROM THE TAKEN KING THE DEAD TO MAKE OUR DAY We’ve finished it! All-access CALL OF DUTY SIDES WITH PS4: pass to the best DLC ever WHAT DOES IT MEAN FOR YOU? ISSUE 114 / OCT 2015 Future Publishing Ltd, Quay House, The Ambury, Welcome Bath BA1 1UA, United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 1225 442244 Fax: +44 (0) 1225 732275 here’s just no stopping the PS4 train. Email [email protected] Twitter @OPM_UK Web www.gamesradar.com/opm With Sony’s super-machine on track to EDITORIAL Editor Matthew Pellett @Pelloki eventually overtake PS2 as the best- Managing Art Editor Milford Coppock @milfcoppock T Production Editor Dom Reseigh-Lincoln @furianreseigh selling console ever, developers keep News Editor Dave Meikleham flocking to Team PlayStation. This month we CONTRIBUTORS Words Alice Bell, Jenny Baker, Ben Borthwick, Matthew Clapham, Ian Dransfield, Matthew Elliott, Edwin Evans-Thirlwell, go behind the scenes of five of the best Matthew Gilman, Ben Griffin, Dave Houghton, Phil Iwaniuk, Jordan Farley, Louis Pattison, Paul Randall, Jem Roberts, Sam games due out this year to show you why Roberts, Tom Sykes, Justin Towell, Ben Wilson, Iain Wilson Design Andrew Leung, Rob Speed the biggest blockbusters of the gaming ADVERTISING world are set to be better on PS4. -

Nekoninexheart2incladultonly

1 / 2 NEKO-NIN.exHeart.2.Incl.Adult.Only.Content-DARKSiDERS Repack ... /NEKO-NIN-exHeart-2-Incl-Adult-Only-Content-DARKSiDERS.html) ... Saiha](https://www.xrel.to/game-nfo/1673048/NEKO-NIN-exHeart-PLUS- ... www.xrel.to/game-nfo/2221429/Millennium-Atoll-REPACK-DARKZER0.html) .... Unlocks optional 18+ Adult Only Content for NEKO-NIN exHeart 2.. Hypersonic 2 windows 7 64 bit real fix!. ... muiple instruments on hypersonic 2 on fl studio ... NEKO-NIN.exHeart.2.Incl.Adult.Only.Content-DARKSiDERS Repack. Adobe Photoshop Lightroom Classic CC 2018 7.0.1.10 Portable X64 Download Pc. 2 / 4 ... NEKO-NIN.exHeart.2.Incl.Adult.Only.Content-DARKSiDERS Repack.. NEKO-NIN exHeart 2 Love +PLUS Free Download PC Game Cracked in Direct Link and Torrent. NEKO-NIN exHeart 2 Love +PLUS - The cat .... Download NEKO-NIN.exHeart.2.Incl.Adult.Only.Content-DARKSiDERS Torrent - RARBG.. Télécharger NEKO-NIN exHeart 2 Incl Adult Only Content-DARKSiDERS sur Cpasbien / Cestpasbien, This is a Sequel to NEKO-NIN exHeart. Japan. From time .... NEKO-NIN exHeart 2. DEVELOPER: Whirlpool. PUBLISHER: Sekai Project. GENRE: Casual, Indie, Nudity, Sexual Content. RELEASE DATE .... REPACK-DARKSiDERS.zip" yEnc (1/6) 3936027, Peter, 07-Oct ... [45783/80977] - "NEKO-NIN.exHeart.PLUS.Saiha.Incl.Adult.Only.Content-DARKSiDERS.zip" ... [45775/80977] - "NEKO-NIN exHeart 2 Love PLUS-DARKSiDERS.zip" yEnc .... Northgard Ragnarok-PLAZA. NEKO-NIN exHeart 2 Incl Adult Only Content-DARKSiDERS. Northgard Ragnarok-PLAZA. Nurse Jackie S06E03 VOSTFR HDTV. Hand.of.Fate.2.The.Servant.and.the.Beast.Update.v1.7.3-PLAZA, PLAZA, 2018-10-30 ... DLC.REPACK-DARKSiDERS, DARKSiDERS, 2018-10-18 .. -

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021

FALL 2021 COURSE BULLETIN School of Visual Arts Division of Continuing Education Fall 2021 2 The School of Visual Arts has been authorized by the Association, Inc., and as such meets the Education New York State Board of Regents (www.highered.nysed. Standards of the art therapy profession. gov) to confer the degree of Bachelor of Fine Arts on graduates of programs in Advertising; Animation; The School of Visual Arts does not discriminate on the Cartooning; Computer Art, Computer Animation and basis of gender, race, color, creed, disability, age, sexual Visual Effects; Design; Film; Fine Arts; Illustration; orientation, marital status, national origin or other legally Interior Design; Photography and Video; Visual and protected statuses. Critical Studies; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts on graduates of programs in Art Education; The College reserves the right to make changes from Curatorial Practice; Design Research, Writing and time to time affecting policies, fees, curricula and other Criticism; and to confer the degree of Master of Arts in matters announced in this or any other publication. Teaching on graduates of the program in Art Education; Statements in this and other publications do not and to confer the degree of Master of Fine Arts on grad- constitute a contract. uates of programs in Art Practice; Computer Arts; Design; Design for Social Innovation; Fine Arts; Volume XCVIII number 3, August 1, 2021 Illustration as Visual Essay; Interaction Design; Published by the Visual Arts Press, Ltd., © 2021 Photography, Video and Related Media; Products of Design; Social Documentary Film; Visual Narrative; and to confer the degree of Master of Professional Studies credits on graduates of programs in Art Therapy; Branding; Executive creative director: Anthony P. -

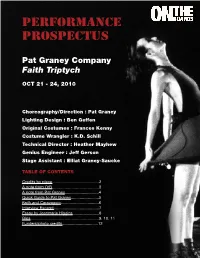

Art and Work in Pat Graney's Faith Triptych

performance prospectus Pat Graney Company Faith Triptych OCT 21 - 24, 2010 Choreography/Direction : Pat Graney Lighting Design : Ben Geffen Original Costumes : Frances Kenny Costume Wrangler : K.D. Schill Technical Director : Heather Mayhew Genius Engineer : Jeff Gerson Stage Assistant : Elliat Graney-Saucke TABLE OF CONTENTS Credits by piece.........................................2 A note from OtB.........................................3 A note from Pat Graney..............................4 Quick Guide to Pat Graney.........................5 Faith and Caravaggio..................................6 Interview Excerpt........................................7 Essay by Jeanmarie Higgins........................8 Bios............................................................9, 10, 11 Funders/photo credits................................12 Faith (premiere 1991) Performers: Nancy Burtenshaw, Deb Rhodes-King, Amii Legendre, KT Niehoff, Sara Parish, Peggy Piacenza, Kim Root Original Cast: Nancy Burtenshaw, Tasha Cook, Pat Graney, Kara O’Toole, Peggy Piacenza, Deb Rhodes-King, Kathryn Stewart Second Cast: Tasha Cook, Pat Graney, Michele Miller, KT Niehoff, Peggy Piacenza, Kim Root, Kathryn Stewart Music: Arvo Part, Cocteau Twins, Lights in a Fat City, Amy Denio, Rachel Warwick Original Lighting Design: Meg Fox Sleep (making peace with the angels) (premiere 1995) Performers: Alison Cockrill, Sandra Fann, Deb Rhodes-King, Maggie Lear, Amii Legendre, Sara Parish, Peggy Piacenza, Kim Root Original Cast: Alison Cockrill, Pat Graney, Robin Jennings-Jaecklein, -

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1 Gabriel Huber Jun 05, 2018 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Authentication..............................................3 1.2 Account Management..........................................5 1.3 Listing.................................................. 21 1.4 Store................................................... 25 1.5 Reviews.................................................. 27 1.6 GOG Connect.............................................. 29 1.7 Galaxy APIs............................................... 30 1.8 Game ID List............................................... 45 2 Links 83 3 Contributors 85 HTTP Routing Table 87 i ii GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 Welcome to the unoffical documentation of the APIs used by the GOG website and Galaxy client. It’s a very young project, so don’t be surprised if something is missing. But now get ready for a wild ride into a world where GET and POST don’t mean anything and consistency is a lucky mistake. Contents 1 GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Authentication 1.1.1 Introduction All GOG APIs support token authorization, similar to OAuth2. The web domains www.gog.com, embed.gog.com and some of the Galaxy domains support session cookies too. They both have to be obtained using the GOG login page, because a CAPTCHA may be required to complete the login process. 1.1.2 Auth-Flow 1. Use an embedded browser like WebKit, Gecko or CEF to send the user to https://auth.gog.com/auth. An add-on in your desktop browser should work as well. The exact details about the parameters of this request are described below. 2. Once the login process is completed, the user should be redirected to https://www.gog.com/on_login_success with a login “code” appended at the end. -

Localizing Japanese Video Games for a Globalizing World

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Open World Translation: Localizing Japanese Video Games for a Globalizing World Emily Suvannasankha University of Central Florida Part of the Game Design Commons, and the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Suvannasankha, Emily, "Open World Translation: Localizing Japanese Video Games for a Globalizing World" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 464. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/464 OPEN WORLD TRANSLATION: LOCALIZING JAPANESE VIDEO GAMES FOR A GLOBALIZING WORLD by EMILY N. SUVANNASANKHA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in English in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Thesis Chair: Madelyn Flammia, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to investigate the most effective ways of handling cultural differences in the Japanese-to-English game localization process. The thesis advocates for applying the Skopos theory of translation to game localization; analyzes how topics such as social issues, humor, fan translation, transcreation, and censorship have been handled in the past; and explores how international players react to developers’ localization choices. -

The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education

The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education Learn Serve Lead Association of December 2020 American Medical Colleges The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education Lisa Howley, PhD Elizabeth Gaufberg, MD, MPH Brandy King, MLIS Association of American Medical Colleges Washington, D.C. The report was funded, in part, by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. Any views, fndings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed here and in related programming or products do not represent those of the foundation or any other grantors. The AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges) is a not-for-proft association dedicated to transforming health through medical education, health care, medical research, and community collaborations. Its members are all 155 accredited U.S. and 17 accredited Canadian medical schools; more than 400 teaching hospitals and health systems, including Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers; and more than 70 academic societies. Through these institutions and organizations, the AAMC leads and serves America’s medical schools and teaching hospitals and their more than 179,000 full-time faculty members, 92,000 medical students, 140,000 resident physicians, and 60,000 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers in the biomedical sciences. Additional information about the AAMC is available at aamc.org. Suggested citation: Howley L, Gaufberg E, King B. The Fundamental Role of the Arts and Humanities in Medical Education. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2020. © 2020 Association of American Medical Colleges. May be reproduced and distributed with attribution for educational and noncommercial purposes only. Contents Acknowledgments v Executive Summary 1 1. Purpose of the Report 3 2.