Oakville's Sustainable Development Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Analysis

Financial Analysis In 2016, Golf Canada recorded a surplus of $99,384 compared to a deficit of $915,495 recognized in 2015. This represents the first surplus since the 2013 fiscal year when $191,695 was recognized. Our staff, partners at the Provincial Golf Associations and nearly 2,500 volunteers from across Canada deserve thanks for their collaboration and valued contributions which resulted in a $1 million increase from last year. Despite headwinds from macro-economic factors and reorganizations of major industry corporations over the past few years for all Canadian golf industry stakeholders, we’re confident that the sport remains ripe with opportunity, excitement, and programming to develop the next generation of athletes. As the National Sport Federation (NSF) for golf in Canada, our mandate is to promote participation and excellence in the game, while ensuring there is capacity for the sport and interaction between all the stakeholders. 2016 was a year in which we made great strides in improving the long- term health of the Association and we look forward to continuing those efforts in the future as we recognize the importance of Golf Canada’s role as a leader in the industry. During the year, there were several positive financial highlights to be proud of: • An increase in total revenue by $1,789,785 (5%) over 2015; • Our core professional championships (RBC Canadian Open and CP Women’s Open) both recognized a surplus in Oakville, Ont. and Priddis, Alta. respectively; • RBC was extended for another six years through 2023 as title -

Forward Looking Statements

TORSTAR CORPORATION 2020 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM March 20, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 1 I. CORPORATE STRUCTURE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 A. Name, Address and Incorporation .......................................................................................................................... 4 B. Subsidiaries ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 II. GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS ....................................................................................................... 4 A. Three-Year History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 B. Recent Developments ............................................................................................................................................. 6 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................................................. 6 A. General Summary................................................................................................................................................... 6 B. -

2003 ANNUAL REPORT 54310 Torstar Cover 3/22/04 9:22 PM Page 1 Page PM 9:22 3/22/04 Cover Torstar 54310 54310 Torstar Cover 3/22/04 9:22 PM Page 3

TORSTAR CORPORATION 2003 ANNUAL REPORT 54310 TorStar Cover 3/22/04 9:22 PM Page 1 54310 TorStar Cover 3/22/04 9:22 PM Page 3 CORPORATE INFORMATION OPERATING COMPANIES – PRODUCTS AND SERVICES TORSTAR DAILY NEWSPAPERS COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS Metroland Printing, Publishing & Distributing is Ontario’s leading publisher of community newspapers, publishing 63 community newspapers in 106 editions. Some of the larger publications include: Ajax/Pickering News Advertiser Aurora/Newmarket Era-Banner Barrie Advance Brampton Guardian Burlington Post Etobicoke Guardian Markham Economist & Sun TORSTAR IS A BROADLY BASED CANADIAN MEDIA COMPANY. Torstar was built on the foundation of its Mississauga News Oakville Beaver flagship newspaper, the Toronto Star, which remains firmly committed to being a great metropolitan Oshawa/Whitby This Week Richmond Hill Liberal newspaper dedicated to advancing the principles of its long-time publisher, Joseph Atkinson. Scarborough Mirror INTERACTIVE MEDIA DAILY PARTNERSHIPS From this foundation, Torstar’s media presence has expanded through Metroland Printing, Publishing & Distributing, and CityMedia Group, which together include almost 100 newspapers and related services, www.thestar.com Sing Tao principally in Southern Ontario. Torstar has also built a major presence in book publishing through Harlequin, which is a leading global publisher of romance and women’s fiction, selling books in nearly 100 countries and SPECIALTY PRODUCTS eye Weekly in 27 languages. Forever Young Real Estate News Toronto.com Torstar strives to be one of Canada’s premier media companies. Torstar and all of its businesses are Car Guide committed to outstanding corporate performance in the areas of maximizing shareholder returns, advancing Boat Guide City Parent editorial excellence, creating a great place to work and having a positive impact in the communities we serve. -

Recruitment and Classified Advertising in Both Community and Daily Newspapers

Recruitment and &ODVVL¿HG$GYHUWLVLQJ Rate Card January 2015 10 Tempo Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M2H 2N8 tel.: 416.493.1300 fax: 416.493.0623 e:DÀLQGHUV#PHWURODQGFRP www.millionsofreaders.com www.metroland.com METROLAND MEDIA GROUP LTD. AJAX/PICKERING - HAMILTON COMMUNITY METROLAND NEWSPAPERS EDITIONS FORMAT PRESS RUNS 1 DAY 2 DAYS 3 DAYS DEADLINES, CONDITIONS AND NOTES Ajax/ Pickering News Advertiser Wed Tab 54,400 3.86 1.96 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Thurs Tab 54,400 Alliston Herald (Modular ad sizes only) Thurs Tab 22,500 1.45 1.20 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Almaguin News Thurs B/S 4,600 0.75 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Ancaster News/Dundas Star Thurs Tab 30,879 1.25 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Arthur Enterprise News Wed Tab 900 0.61 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Barrie Advance/Innisfil/Journal Thurs Tab 63,800 2.95 2.33 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication (Modular ad sizes only) Belleville News Thurs Tab 23,715 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bloor West Villager Thurs Tab 34,300 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bracebridge Examiner Thurs Tab 8,849 1.40 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Bradford West Gwillimbury Topic Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication - Material & Thurs Tab 10,700 1.00 (Modular ad sizes only) Booking **Process Color add 25%, Spot add 15%, up to $350 Brampton Guardian/ Wed Tab 240,500 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication. -

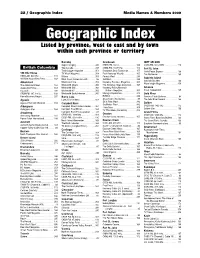

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Tom Mcbroom, B.L.A

LPAT Case Nos. PL 171084 PL180158 PL180580 MM180022 MM170004 LOCAL PLANNING APPEAL TRIBUNAL PROCEEDING COMMENCED UNDER subsection 22(7) of the Planning Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. P. 13, as amended Applicant and Appellant: Clublink Corporation ULC and Clublink Holdings Ltd. Subject: Request to amend the Official Plan - Refusal of request by the Town of Oakville Existing Designation: Private Open Space and Natural Area Proposed Designation: Site Specific (to be determined) - including Residential, Mixed Use and Community Commercial Purpose: To permit the redevelopment of the Subject Lands for a mix of residential, commercial, and open space uses Property Address/Description: 1333 Dorval Drive Municipality: Town of Oakville Approval Authority File No.: OPA.1519.09 LPAT Case No.: PL171084 LPAT File No.: PL171084 LPAT Case Name: Clublink Corporation ULC v. Oakville (Town) See Appendix "A" WITNESS STATEMENT OF THOMAS McBROOM Prepared for ClubLink Corporation ULC and ClubLink Holdings Limited May 17,2021 Qualifications 1. I am the owner of Thomas McBroom Associates Ltd., a company that specializes in golf course architecture and design. 2. I hold a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture degree from the University of Guelph, which I obtained in 1975. 3. Following my graduation from the University of Guelph, I worked for a number of firms in general landscape architecture. 2 4. My interest was in golf course design, however, and by the mid-1980s, I had started my own company. Since then, I have focused exclusively on the design and construction supervision of golf courses, throughout Canada and globally. 5. There are only five or six firms in Canada that specialize in golf course design, and approximately 50 or 60 companies in the United States. -

Lakeview: Journey from Yesterday Kathleen A

Lakeview: Journey From Yesterday Kathleen A. Hicks LAKEVIEW: JOURNEY FROM YESTERDAY is published by The Friends of the Mississauga Library System 301 Burnhamthorpe Road, West, Mississauga, Ontario, L5B 3Y3 Copyright © 2005 by the Mississauga Library System All rights reserved Lakeview: Journey From Yesterday ISBN 0-9697873-6-7 II Written by Kathleen A. Hicks Cover design by Stephen Wahl Graphic layout by Joe and Joyce Melito Lakeview Sign by Stephen Wahl Back Cover photo by Stephen Wahl No part of this publication may be produced in any form without the written permission of the Mississauga Library System. Brief passages may be quoted for books, newspaper or magazine articles, crediting the author and title. For photographs contact the source. Extreme care has been taken where copyright of pictures is concerned and if any errors have occurred, the author extends her utmost apology. Care also has been taken with research material. If anyone encounters any discrepancy with the facts contained herein, (Region of Peel Archives) please send your written information to the author in care of the Mississauga Library System. Lakeview: Journey From Yesterday Other Books By Kathleen A. Hicks (Stephen Wahl) III The Silverthorns: Ten Generations in America Kathleen Hicks’ V.I.P.s of Mississauga The Life & Times of the Silverthorns of Cherry Hill Clarkson and its Many Corners Meadowvale: Mills to Millennium VIDEO Riverwood: The Estate Dreams are Made of IV Dedication dedicate this book to my family, the Groveses of Lakeview, where I was born. My grandfather, Thomas Jordan, and my father, Thomas Henry, were instrumental in building many houses and office buildings across southern Ontario. -

Proudly Representing Ontario's Community Newspapers 310

We deliver Ontario - in PRINT and ONLINE! Reach engaged and involved Ontarians in just one call, one buy, one invoice Proudly Representing Ontario’s Community Newspapers * 310 newspapers reaching 5.8 million households NOW Ad*Reach represents their Online Community News Sites! * 190 Community News Sites with Average Monthly Impressions of 12 Million. Advertise on All Ontario sites or through a combination of geographic zones Rates: Specs: $17 CPM Net Per Order * Leaderboard ads (728 x 90 pixels) Volume Rates Available * File size up to 40 kilobyte, in gif, * Book All Ontario sites, jpg or standard flash format or a combination of geographic zones * Ads published Run of Site (ROS) * Bookings and ad material must be received 5 days prior to launch Let us assist you in your campaign planning Ad*Reach Ontario (adreach.ca) Ted Brewer Minna Schmidt National Account Manager Manager of Sales 416-350-2107 ext 24 416-350-2107 ext 22 [email protected] [email protected] A division of the Ontario Community Newspapers Association Ontario's Local Community News Sites Zone Community News URL Associated Community Newspaper ALL OF ONTARIO 190 Newspapers Average Monthly Impressions 12 Million Or A Combination Of: ZONE 1 ‐ SOUTHWEST ONTARIO amherstburgecho.com Amherstburg Echo 40 Newspapers northhuron.on.ca Blyth/Brussels Citizen Average Monthly cambridgetimes.ca Cambridge Times Impressions chathamthisweek.com Chatham This Week 908,000 clintonnewsrecord.com Clinton News Record delhinewsrecord.com Delhi News Record northkentleader.com Dresden/Bothwell Leader -

The Oakville Beaver Weekend, Saturday January 17, 2009 the Oakville Beaver Commentary 467 Speers Rd., Oakville Ont

6 - The Oakville Beaver Weekend, Saturday January 17, 2009 www.oakvillebeaver.com The Oakville Beaver Commentary 467 Speers Rd., Oakville Ont. L6K 3S4 (905) 845-3824 Fax: 337-5567 Classified Advertising: 905-632-4440 Circulation: 845-9742 Guest Columnist The Oakville Beaver is a member of the Ontario Press Council. The council is located at 80 Gould St., Suite 206, Toronto, Ont., M5B 2M7. Phone (416) 340-1981. Advertising is accepted on the condition that, in the event of a typographical error, that portion of advertising space occupied by the erroneous item, together with a reasonable allowance for signature, will not be charged for, but the balance of the advertisement will be paid for at the applicable rate.The publisher reserves the right to categorize advertisements or decline. Editorial and advertising content of the Oakville Beaver is protected by copyright. Unauthorized use is prohibited. NEIL OLIVER Vice-president and Group Publisher, SANDY PARE Business Manager Planning strong Metroland West MARK DILLS Director of Production DAVID HARVEY General Manager MANUEL GARCIA Production Manager JILL DAVIS Editor in Chief CHARLENE HALL Director of Distribution future together ROD JERRED Managing Editor SARAH MCSWEENEY Circ. Manager DANIEL BAIRD Advertising Director WEBSITE oakvillebeaver.com Kevin Flynn, Oakville MPP RIZIERO VERTOLLI Photography Director or many of us, the end of the year and the holiday sea- Metroland Media Group Ltd. includes: Ajax/Pickering News Advertiser, Alliston Herald/Courier, Arthur Enterprise News, Barrie Advance, -

Page 1 of 3 Insidehalton Article: Shocking Donation 29/12/2010 Http

InsideHalton Article: Shocking donation Page 1 of 3 Movies | Photos | Videos | Slideshows | Print Editions OVERCAST -1°C | WEATHER FORECAST Connect with Facebook | Login/Register Articles Photos Videos Businesses Enter Search Text ... Home News Sports What's On Opinion Community Announcements Jobs Used Cars Real Estate Rentals Classifieds Flyers Home » Shocking donation ... Small - Large | Print | Email | Add to Favourites | Featured Angela Blackburn/Oakville Beaver | Nov 01, 2010 - 5:17 PM | 4 Catherine O’Hara, Metroland West media Group | Dec 29 Shocking donation Halton police sergeant reaches out to Village of Hope Ontario Liberals list Oakville Hydro as $15,000 campaign contributor A staff sergeant with the Halton Regional Police, Gavin Hayes is Oakville taxpayers may be lining up eager to help... behind the Ontario NDP and others this week asking why Oakville Hydro donated just over $15,000 to the Ontario Liberal Party — in general in Featured Video 2008 and to a cottage country by- election in 2009. That’s according to Ontario Elections contributions statements brought to light yesterday by the Ontario NDP. But Oakville Hydro CEO and president Rob Lister said Oakville Hydro Corporation purchased a table at an annual heritage dinner, held in Toronto, an annual business networking event for the years and amounts in question. “The situation is that back in 2009, Shocking donation. Oakville Hydro purchased a table at the heritage dinner,” Lister told The Oakville Beaver Monday. Lister said the political party contribution is “unrelated.” “Oakville Hydro Corporation purchased a table,” said Lister, indicating he wasn’t aware what the organizers did with the funds raised by the dinner. -

Out of the Rough: How Can Municipalities Better Utilize Their Golf Course Lands?

OUT OF THE ROUGH: HOW CAN MUNICIPALITIES BETTER UTILIZE THEIR GOLF COURSE LANDS? By Darcy James Watt Bachelor of Arts Honours, Laurentian University, 2017 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Planning In Urban Development Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2019 © Darcy James Watt 2019 Author’s Declaration for Electronic Submission of a MRP I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. i OUT OF THE ROUGH: HOW CAN MUNICIPALITIES BETTER UTILIZE THEIR GOLF COURSE LANDS? © Darcy James Watt, 2019 Master of Planning In Urban Development Ryerson University ABSTRACT Golf has declined in recent years as younger generations fail to take up the sport leaving many municipally-owned golf courses in financial trouble. As cities face numerous growing challenges such as housing, public transit and the lack of public greenspaces, closing municipal golf courses has been touted as a possible solution. While municipal golf courses are open to the public, barriers to entry such as a dress code and green fees have left them inaccessible to many residents making them not truly public spaces. -

2005 1 First Tee TABLE of CONTENTS

2006 GAO tentative schedule Oshawa Golf & Curling Club Beck’s Non-Alcoholic Beer Investors Group Family Classic Men’s Better-Ball Championship Men’s Amateur Championship Mill Run Golf & Country Club, Uxbridge Oakdale Golf & Country Club, Downsview Oshawa Golf & Curling Club, Oshawa August 28-29, 2006 May 18, 2006 July 11-14, 2006 Junior & Juvenile Boys’ Better-Ball Championship Investors Group Bantam Girls’ Championship Port Colborne Golf & Country Club, Port Colborne Junior Tournament of Champions Willow Valley Golf Club, Hamilton August 24, 2006 Wooden Sticks Golf Club, Uxbridge July 18-19, 2006 May 20-22, 2006 Investors Group Investors Group Women’s Mid-Amateur Championship Women’s Champion of Champions Junior & Juvenile Girls’ Championship Timberwolf Golf Club, Sudbury Credit Valley Golf & Country Club, Mississauga Willow Valley Golf Club, Hamilton August 29-31, 2006 June 6, 2006 July 18-20, 2006 Mixed Championship Clublink Investors Group Wooden Sticks Golf Club, Uxbridge Men’s Match Play Championship Junior & Juvenile Boys’ Championship September 4, 2006 Rocky Crest Golf Club, Mactier Whitewater Golf Club, Thunder Bay June 6-9, 2006 July 18-21, 2006 Men’s & Women’s Public Player Championships Osprey Valley Resorts, Alton Senior Men’s Champion of Champions Bantam Boys’ Championship September 5-6 (Men’s) - September 6, 2006 (Women’s) RiverBend Golf Community, London Puslinch Lake Golf Club, Cambridge June 12, 2006 July 24-26, 2006 George S. Lyon Championship Cedar Brae Golf & Country Club, Scarborough Beck’s Non-Alcoholic Beer Investors