Ancient Tales of Giants from Qumran and Turfan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Priesthood, Cult, and Temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran

PRIESTHOOD, CULT, AND TEMPLE IN THE ARAMAIC SCROLLS PRIESTHOOD, CULT, AND TEMPLE IN THE ARAMAIC SCROLLS FROM QUMRAN By ROBERT E. JONES III, B.A., M.Div. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Robert E. Jones III, June 2020 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2020) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Priesthood, Cult, and Temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran AUTHOR: Robert E. Jones III, B.A. (Eastern University), M.Div. (Pittsburgh Theological Seminary) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Daniel A. Machiela NUMBER OF PAGES: xiv + 321 ii ABSTRACT My dissertation analyzes the passages related to the priesthood, cult, and temple in the Aramaic Scrolls from Qumran. The Aramaic Scrolls comprise roughly 15% of the manuscripts found in the Qumran caves, and testify to the presence of a flourishing Jewish Aramaic literary tradition dating to the early Hellenistic period (ca. late fourth to early second century BCE). Scholarship since the mid-2000s has increasingly understood these writings as a corpus of related literature on both literary and socio-historical grounds, and has emphasized their shared features, genres, and theological outlook. Roughly half of the Aramaic Scrolls display a strong interest in Israel’s priestly institutions: the priesthood, cult, and temple. That many of these compositions display such an interest has not gone unnoticed. To date, however, few scholars have analyzed the priestly passages in any given composition in light of the broader corpus, and no scholars have undertaken a comprehensive treatment of the priestly passages in the Aramaic Scrolls. -

The Qumran Collection As a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sidnie White Crawford Publications Classics and Religious Studies 2016 The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/crawfordpubs This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sidnie White Crawford Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Qumran Collection as a Scribal Library Sidnie White Crawford Since the early days of Dead Sea Scrolls scholarship, the collection of scrolls found in the eleven caves in the vicinity of Qumran has been identified as a library.1 That term, however, was undefined in relation to its ancient context. In the Greco-Roman world the word “library” calls to mind the great libraries of the Hellenistic world, such as those at Alexandria and Pergamum.2 However, a more useful comparison can be drawn with the libraries unearthed in the ancient Near East, primarily in Mesopotamia but also in Egypt.3 These librar- ies, whether attached to temples or royal palaces or privately owned, were shaped by the scribal elite of their societies. Ancient Near Eastern scribes were the literati in a largely illiterate society, and were responsible for collecting, preserving, and transmitting to future generations the cultural heritage of their peoples. In the Qumran corpus, I will argue, we see these same interests of collection, preservation, and transmission. Thus I will demonstrate that, on the basis of these comparisons, the Qumran collection is best described as a library with an archival component, shaped by the interests of the elite scholar scribes who were responsible for it. -

3161532813 Lp.Pdf

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber/Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber/Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) · James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) · Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 335 Loren T. Stuckenbruck The Myth of Rebellious Angels Studies in Second Temple Judaism and New Testament Texts Mohr Siebeck L T. S, born 1960; BA Milligan College, MDiv and PhD Princeton Theological Seminary; teaching positions at Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel, Durham University and Princeton Theological Seminary; since 2012 Professor of New Testament (with emphasis on Second Temple Judaism) at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München. e-ISBN PDF 978-3-16-153281-8 ISBN 978-3-16-153024-1 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament) Die Deutsche Nationalibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2014 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tion, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by epline in Kirchheim/Teck, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non- aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface The present volume brings together some unpublished and mostly published (yet updated) material. The common thread that links the chapters of this book is a concern to explore the myth of rebellious angels in some of its Second Temple Jewish setting and to inquire into possible aspects of its reception, including among writings belonging to what we now call the New Testament. -

THE LETTER of JUDE's USE of 1 ENOCH: the BOOK of the WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK Submitted in Accordance with T

THE LETTER OF JUDE'S USE OF 1 ENOCH: THE BOOK OF THE WATCHERS AS SCRIPTURE by LAWRENCE HENRY VANBEEK submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of NEW TESTAMENT at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: Professor J. E. BOTHA November 1997 I declare that The Letter ofJude's Use Of I Enoch: The Book Of The Watchers is my own work and that all of the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated or acknowledged by means of complete references. /f/ri.ll~ Lawrence Henry VanBeek Preface This thesis attempts to show that I Enoch: The Book of the Watchers (BW) was authoritative and therefore canonical literature for both the audience of Jude and for its author. To do this the possibility of some fluctuation in the third part of the canon until the end of the first century AD for groups outside of the Pharisees is examined; then three steps are taken showing that: I. Jubilees and the Qumran literature used BW and considered it authoritative. The Damascus Document and the Genesis Apocryphon both alluded to BW. Qumran also used Jubilees which used BW. 2. The New Testament used BW in several places. The most obvious places are Jude 6, 14 and 2 Peter 2: 4. Jude in particular used a quotation formula which other New Testament passages used to introduce authoritative literature. 3. The Apostolic and Church Fathers recognized that Jude used BW authoritatively. The final chapter deals with the specific arguments of R. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible

The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bible James C. VanderKam WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN / CAMBRIDGE, U.K. © 2oi2 James C. VanderKam AU rights reserved Published 2012 by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 / P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K. Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 7654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data VanderKam, James C. The Dead Sea scrolls and the Bible / James C. VanderKam. p. cm. "Six of the seven chapters in The Dead Sea scrolls and the Bible began as the Speaker's Lectures at Oxford University, delivered during the first two weeks of May 2009" — Introd. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8028-6679-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) L. Dead Sea scrolls. 2. Dead Sea scrolls — Relation to the Old Testament. 3. Dead Sea scrolls — Relation to the New Testament. 4. Judaism — History — Post-exilic period, 586 B.c-210 A.D. I. Title. BM487.V255 2012 22i.4'4 — dc23 2011029919 www.eerdmans.com Contents INTRODUCTION IX ABBREVIATIONS XÜ ι. The "Biblical" Scrolls and Their Implications ι Number of Copies from the Qumran Caves 2 Other Copies 4 Texts from Other Judean Desert Sites 5 Nature of the Texts 7 General Comments 7 The Textual Picture 9 An End to Fluidity 15 Conclusions from the Evidence 15 New Evidence and the Text-Critical Quest 17 2. Commentary on Older Scripture in the Scrolls 25 Older Examples of Interpretation 28 In the Hebrew Bible 28 Older Literature Outside the Hebrew Bible 30 Scriptural Interpretation in the Scrolls 35 ν Continuous Pesharim 36 Other Forms of Interpretation 38 Conclusion 47 3. -

The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism. Nancy Perkins East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2011 The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism. Nancy Perkins East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Perkins, Nancy, "The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1397. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1397 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History _____________________ by Nancy Perkins December 2011 _____________________ William D. Burgess Jr., PhD, Chair Keith Green, PhD Henry Antkiewicz, PhD Keywords: Book of Enoch, Judaism, Second Temple ABSTRACT The Book of Enoch and Second Temple Judaism by Nancy Perkins This thesis examines the ancient Jewish text the Book of Enoch, the scholarly work done on the text since its discovery in 1773, and its seminal importance to the study of ancient Jewish history. Primary sources for the thesis project are limited to Flavius Josephus and the works of the Old Testament. Modern scholars provide an abundance of secondary information. -

Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies

0 Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies Bibliography largely taken from Dr. James R. Davila's annotated bibliographies: http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~www_sd/otpseud.html. I have changed formatting, added the section on 'Online works,' have added a sizable amount to the secondary literature references in most of the categories, and added the Table of Contents. - Lee Table of Contents Online Works……………………………………………………………………………………………...02 General Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...…03 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………....03 Translations of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in Collections…………………………………….…03 Guide Series…………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 On the Literature of the 2nd Temple Period…………………………………………………………..........04 Literary Approaches and Ancient Exegesis…………………………………………………………..…...05 On Greek Translations of Semitic Originals……………………………………………………………....05 On Judaism and Hellenism in the Second Temple Period…………………………………………..…….06 The Book of 1 Enoch and Related Material…………………………………………………………….....07 The Book of Giants…………………………………………………………………………………..……09 The Book of the Watchers…………………………………………………………………………......….11 The Animal Apocalypse…………………………………………………………………………...………13 The Epistle of Enoch (Including the Apocalypse of Weeks)………………………………………..…….14 2 Enoch…………………………………………………………………………………………..………..15 5-6 Ezra (= 2 Esdras 1-2, 15-16, respectively)……………………………………………………..……..17 The Treatise of Shem………………………………………………………………………………..…….18 The Similitudes of Enoch (1 Enoch 37-71)…………………………………………………………..…...18 The -

Dead Sea Scrolls—Criticism, Interpretation, Etc.—Congresses

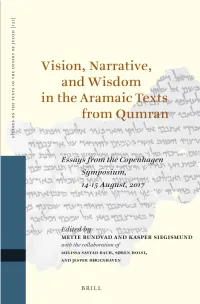

Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran Studies on the Texts of the Desert of Judah Edited by George J. Brooke Associate Editors Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar Jonathan Ben-Dov Alison Schofield volume 131 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/stdj Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran Essays from the Copenhagen Symposium, 14–15 August, 2017 Edited by Mette Bundvad Kasper Siegismund With the collaboration of Melissa Sayyad Bach Søren Holst Jesper Høgenhaven LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: International Symposium on Vision, Narrative, and Wisdom in the Aramaic Texts from Qumran (2017 : Copenhagen, Denmark) | Bundvad, Mette, 1982– editor. | Siegismund, Kasper, editor. | Bach, Melissa Sayyad, contributor. | Holst, Søren, contributor. | Høgenhaven, Jesper, contributor. Title: Vision, narrative, and wisdom in the Aramaic texts from Qumran : essays from the Copenhagen Symposium, 14–15 August, 2017 / edited by Mette Bundvad, Kasper Siegismund ; with the collaboration of Melissa Sayyad Bach, Søren Holst, Jesper Høgenhaven. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2020] | Series: Studies on the texts of the desert of Judah, 0169-9962 ; volume 131 | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019029284 | ISBN 9789004413702 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004413733 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Dead Sea scrolls—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—Congresses. | Dead Sea scrolls—Relation to the Old Testament—Congresses. | Manuscripts, Aramaic—West Bank—Qumran Site—Congresses. Classification: LCC BM487 .I58 2017 | DDC 296.1/55—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019029284 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

The Origin of Evil Spirits

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament · 2. Reihe Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) 198 Archie T. Wright The Origin of Evil Spirits The Reception of Genesis 6:1– 4 in Early Jewish Literature Second, revised edition Mohr Siebeck Archie T. Wright, born 1958; PhD, University of Durham; Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at Regent University, Virginia, USA. ISBN 978-3-16-151031-1 / eISBN 978-3-16-157496-2 unveränderte eBook-Ausgabe 2019 ISSN 0340-9570 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament, 2. Reihe) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliogra- phie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2013 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Laupp & Göbel in Nehren on non-aging paper and bound by Buch- binderei Nädele in Nehren. Printed in Germany. Table of Contents Preface to the Second, Revised Edition .................................................. IX Preface to the First Edition ..................................................................... XI Abbreviations.........................................................................................XVI -

Gilgamesh the Giant: the Qumran Book of Giants' Appropriation of Gilgamesh Motifs Matthew J

Florida State University Libraries Faculty Publications Department of Religion 2009 Gilgamesh the Giant: The Qumran Book of Giants' Appropriation of Gilgamesh Motifs Matthew J. Goff Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Dead Sea Discoveries 16 (2009) 21–53 www.brill.nl/dsd Gilgamesh the Giant: !e Qumran Book of Giants’ Appropriation of Gilgamesh Motifs Matthew Goff Dodd Hall M05, Department of Religion, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306, U.S.A. mgoff@fsu.edu Abstract "e Qumran Book of Giants shows familiarity with lore from the classic Meso- potamian Epic of Gilgamesh. It has been proposed that the author of the Book of Giants drew from the epic in order to polemicize against it. "ere is much to commend this view. "e name of the hero of the tale is given to one of the mur- derous, wicked giants of the primordial age. Examination of fragments of the Book of Giants, in particular 4Q530 2 ii and 4Q531 22, however, suggest that key aspects of its portrayal of Gilgamesh the giant cannot be explained as polemic against Mesopotamian literary traditions. "e Book of Giants creatively appro- priates motifs from the epic and makes Gilgamesh a character in his own right in ways that often have little to do with Gilgamesh. Keywords Book of Giants; Gilgamesh 1. Introduction1 Many writings of the Hebrew Bible and Early Judaism can be elucidated through comparison with ancient Near Eastern texts, but few mention specific details from them. One exception is the fascinating but fragmen- tary Aramaic composition from Qumran known as the Book of Giants.2 1 I thank Eibert Tigchelaar for his assistance in helping me think through the main Book of Giants texts discussed in this article and Clare Rothschild for her comments on an earlier draft. -

1 Enoch 1–36: the Book of Watchers: a Review of Recent Research

Chapter 2 1 Enoch 1–36: The Book of Watchers: A Review of Recent Research 2.1 Introduction Since the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, there has been an increasing interest by scholars in 1 Enoch 1–36, the Book of Watchers. This is due primarily to the publication of the 4QEn fragments by J.T. Milik in 1976. Milik presents a major edition that contains the Aramaic fragments of 1 Enoch from Qumran Cave 4.1 He has included the text of the fragments, his translation and notes, and his reconstruction of the text. Milik provides an evaluation of the extant literature by comparing what he calls “specimens of the original text” to his reconstruction and translation, while also offering an introduction to the history of the early Enochic literature. The major problem with Milik’s book, as many have pointed out, 2 is that in many places the Aramaic text he presents is in fact a reconstruction based on his comparison of the 4QEn fragments with the extant Greek and Ethiopic texts. To this end, he has been properly criticized; his work all too easily may lead to the illusion that a great deal more of the Aramaic documents is extant from Qumran than is actually the case. However, the contribution of Milik’s work far outweighs its shortcomings. As a result of the publication of the Qumran material, several theories have been set forth that consider the major areas of concern about BW (i.e. date, place and authorship, source criticism of the myths behind BW; and interpretation of the function of BW). -

Pesher and Periodization1

Dead Sea Discoveries 18 (2011) 129–154 brill.nl/dsd Pesher and Periodization1 Shani Tzoref [email protected] Abstract in ,פתר This study re-examines the use of the termpesher , and the related root Qumran compositions, and their significance with respect to conceptions of determinism and periodization in the corpus. It discusses how the treatment of the book of Genesis in 4Q180, 4Q252, and the Admonitions sections of the Damascus Document reflect a worldview and hermeneutic that are generally associ- ated with the continuous and thematic pesharim at Qumran. Pesher compositions reveal how scripture is fulfilled in current events. These related works demonstrate the fulfillment of the divine grand plan in scripture and past events. It is suggested that these texts share a “performative” aspect: in all of these compositions, the act of transmitting divinely-revealed knowledge is as much an actualization and ful- fillment of eschatological expectations as the unfolding social and political history that is tied to the texts. Keywords pesher; periodization; Jubilees; 4Q252; 4Q180; Qumran; performative texts 1 This article is the last of a series of three publications based upon a paper I delivered at the Fifteenth World Congress of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, in August 5, 2009. The oral presentation was entitled, “4Q252 and the Heavenly Tablets.” The first of these articles will appear in a Festschrift dedicated to the memory of Prof. Hanan Eshel: Shani Tzoref, “4Q252: Listenwissenschaft and Covenantal Patriarchal Blessings,” in “Go Out and Study the Land” (Judg 18:2): Historical and Archaeological Studies in Honor of Hanan Eshel (ed. Aren Maeir, Jodi Magness, and Lawrence H.