0848033066965.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

HISTORY OF THE PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA For more than 119 years, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra has been an essential part of Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape. The Pittsburgh Symphony, known for its artistic excellence, is credited with a rich history of the world’s finest conductors and musicians, and a strong commitment to the Pittsburgh region and its citizens. This tradition was furthered in fall 2008, when Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck assumed the position of music director with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Heading the list of internationally recognized conductors to have led the Pittsburgh Symphony is Victor Herbert, music director between 1898 and 1904, who influenced the early development of the symphony. Preceding Herbert was Frederic Archer (1896-1899), the first Pittsburgh Orchestra conductor. The symphony’s solidification as an American institution took place in the late 1930s under the direction of Maestro Otto Klemperer. Conductors prior to Klemperer were Emil Paur (1904-1910), Elias Breeskin (1926-1930) and Antonio Modarelli (1930-1937). From 1938 to 1948, under the dynamic directorship of Fritz Reiner, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra embarked on a new phase of its history, making its first international tour and its first commercial recording. The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra’s standard of excellence was maintained and enhanced through the inspired leadership of William Steinberg during his quarter-century as music director between 1952 and 1976. André Previn (1976-1984) led the Orchestra to new heights through tours, recordings and television, including the PBS series, “Previn and the Pittsburgh.” Lorin Maazel began his relationship with the Pittsburgh Symphony in 1984 as music consultant but later served as a highly regarded music director from 1988 to 1996. -

Salle Pleyel

VENDREDI 6 SEPTEMBRE - 20H Piotr Ilitch Tchaïkovski Concerto pour piano n° 1 entracte Richard Strauss Une vie de héros septembre 2013 septembre | Vendredi 6 | Vendredi Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra Manfred Honeck, direction Yuja Wang, piano Concert diffusé le 2 octobre à 20h sur France Musique. Fin du concert vers 22h. Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra Orchestra Symphony Pittsburgh Piotr Ilitch Tchaïkovski (1840-1893) Concerto pour piano et orchestre n° 1 en si bémol mineur op. 23 Allegro non troppo et molto maestoso Andantino semplice Allegro con fuoco Composition : 1874-février 1875. Révisions : été 1879, décembre 1888. Dédicace : d’abord à Nikolaï Rubinstein, puis à Hans von Bülow. Création : 13 octobre 1875, à Boston, par Hans von Bülow au piano et le Boston Symphony Orchestra sous la direction de Benjamin Boston Lang. Durée : environ 35 minutes. La dialectique soliste versus orchestre, élaborée par le concerto classique et portée à son apogée par le romantisme, joue à plein dans le Concerto pour piano n° 1 de Tchaïkovski, qui est aujourd’hui l’un des concertos pour piano les plus aimés et les plus interprétés du répertoire, aux côtés du Concerto « Empereur » de Beethoven ou des Concertos n° 2 et 3 de Rachmaninov. La réaction du grand pianiste Nicolaï Rubinstein, lorsque Tchaïkovski soumit à l’automne 1874 la partition tout juste achevée à son approbation, ne laissait pourtant pas augurer d’un tel succès. Le compositeur, novice dans l’art du concerto, avait voulu l’avis d’un virtuose sur l’écriture de la partie soliste (Tchaïkovski était bon pianiste, mais n’avait rien d’un prodige du clavier à la Rachmaninov ou à la Prokofiev). -

“A Combination of European Musicianship and American

A History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra For more than 115 years, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO) has been an essential part of Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape. The PSO, known for its artistic excellence, is credited with a rich history of the world’s finest conductors and musicians, and a strong commitment to the Pittsburgh region and its citizens. This tradition was furthered in fall 2008, when Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck assumed the position of Music Director with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Heading the list of internationally recognized conductors to have led the PSO is Victor Herbert, Music Director between 1898 and 1904, who influenced the early development of the PSO. Preceding Herbert was Frederic Archer (1896-1899), the first Pittsburgh Orchestra Conductor. The Orchestra’s solidification as an American institution took place in the late 1930s under the direction of Maestro Otto Klemperer. Conductors prior to Klemperer were Emil Paur (1904- 1910), Elias Breeskin (1926-1930) and Antonio Modarelli (1930-1937). From 1938 to 1948, under the dynamic directorship of Fritz Reiner, the Orchestra embarked on a new phase of its history, making its first international tour and its first commercial recording. The PSO’s standard of excellence was maintained and enhanced through the inspired leadership of William Steinberg during his quarter-century as Music Director between 1952 and 1976. André Previn (1976-1984) led the Orchestra to new heights through tours, recordings and television, including the PBS series, Previn and the Pittsburgh. Lorin Maazel began his relationship with the PSO in 1984 as Music Consultant but later served as a highly regarded Music Director from 1988-1996. -

BALADA, LEES, ZWILICH New World Records 80503

BALADA, LEES, ZWILICH New World Records 80503 As an idea, the concerto is as old as African call and response songs or the actor-chorus convention of Greek theater. In its manifestations in Western music, the concerto form has shown remarkable resiliency over the past 400 years, from its documented birth in the late 1500s as church music for groups of musicians, the concerto da chiesa, through its secular manifestations pioneered by Torelli, who published in 1686 a concerto da camera for two violins and bass, and its subsequent elaborations leading to the poised musical essays for soloist and orchestra of the late 1700s and early 1800s, and the epic transfigurations resulting in the massive “piano symphonies” of the late nineteenth century. Throughout the twentieth century, the concerto has continued to evolve, although along familiar grooves. Stravinsky, Bartók, Prokofiev, Berg, Schoenberg, Strauss, Barber, Diamond, Poulenc, de Falla, Hindemith, Sibelius, Elgar, Holst, Sessions, Carter, Rorem, Copland, Gershwin, Persichetti, and many other composers have written works that continued the tradition, infusing their concertos- -or, in some cases, works that were concertos although they did not bear the name--with idioms of their own rather than radically reinventing the form. If anything, the concerto of the final decades of the twentieth century is slimmer, leaner, more concentrated than its titanic Romantic predecessor. A kind of musical liposuction practiced by composers, perhaps, in reaction to the persistence of the high-fat diet of the Post-Wagnerians? As a format, the concerto has remained rather stable from Vivaldi and Bach onward: The solo instrument is profiled through a series of fast and slow movements against an instrumental group, a chamber ensemble or a full orchestra. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001

FEEL READY LEARN THE ART OF PERFORMANCE, so you can feel an audience rise to its feet. Learn the rules of logic, so you can feel the heat of debate. Learn the discipline of riding, so you can feel the joy of a perfect jump. Stoneleigh-Burnham School. Feel Ready. College Prep Program for Girls, Grades 9-12 Nationally Recognized Riding Program Specializing in the Arts, Debate & Athletics Extensive Science Program STONELEIGH- Including Equine Science Class BURNHAMn SCHOOL Call admissions at 413-774-2711 or visit www.sbschool.org A College Preparatory School for Young Women Since 1 869 Greenfield, Massachusetts MM Table of Contents Prelude Concert of Friday, July 6, at 6 3 Members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra MUSIC OF MOZART AND PONCHIELLI Boston Symphony Orchestra concert of Friday, July 6, at 8:30 13 Seiji Ozawa conducting; Mstislav Rostropovich, cello; Steven Ansell, viola MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN AND STRAUSS Boston Symphony Orchestra concert of Saturday, July 7, at 8:30 25 Rafael Friihbeck de Burgos conducting; Itzhak Perlman, violin MUSIC OF MOZART AND STRAUSS Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra concert of Sunday, July 8, at 2:30 34 Mariss Jansons conducting MUSIC OF MOZART, STRAUSS, AND TCHAIKOVSKY Ozawa Hall concert of Wednesday, July 11, at 8:30 49 Matthias Goerne, baritone; Eric Schneider, piano SCHUBERT "DIE SCHONE MULLERIN" SATURDAY-MORNING OPEN REHEARSAL SPEAKERS, JULY 2001 July 7 and 28 — Robert Kirzinger, BSO Publications Associate July 14 and 21 — Marc Mandel, BSO Director of Program Publications You are invited to take Tanglewood Guided Tours of Tanglewood sponsored by the Tanglewood Association of the Boston Symphony Association of Volunteers. -

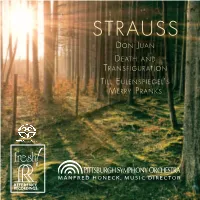

Strauss Don Juan

STRAUSS DON JUAN DEATH AND TRANSFIGURATION TILL EULENSPIEGEL’S MERRY PRANKS fresh! MANFRED HONECK, MUSIC DIRECTOR Richard Strauss from a photograph by Fr. Müller, Munich here are few composers who have such an impressive ability to depict a story together with single existential moments in instrumental music as Richard Strauss in his Tondichtungen (“tone poems”). Despite the clear structure that the music follows, a closer interpretative look reveals many unanswered questions. FTor me, it was the in-depth discovery and exploration of these details that appealed to me, as the answers resulted in surprising nuances that helped to shape the overall sound of the pieces. One such example is the opening of Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) where it is obvious that the person on the deathbed breathes heavily, characterized by the second violins and violas in a syncopated rhythm. What does the following brief interjection of the flutes mean? The answer came to me while thinking about my own dark, shimmering farmhouse parlor where I lived as a child. There, we had only a sofa and a clock on the wall that interrupted the silence. The flutes remind me of the ticking clock hand. This is why it has to sound sober, unemotional, mechanistic and almost metallic. Another such example is the end of Don Juan where the strings seem to tremble. It is here that one can hear the last convulsions of the hero’s dying body. This must sound nervous, dreadful and dramatic. For this reason, I took the liberty to alter the usual sound. I ask the strings to gradually transform the tone into an uncomfortable, convulsing, and shuddering ponticello until the final pizzicato marks the hero’s last heartbeat. -

Pittsburgh Concert Programs at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Use Command F (⌘F) or CTRL + F to search this document ORGANIZATION DATE YEAR PROGRAM VENUE LOCATION John H. Mellor 11/27/1855 1855 Soiree by the pupils of Mrs. Ernest Piano warerooMs Music of John H. Mellor DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #41 Protestant Episcopal Church of 12/29/1856 1856 Concert of Sacred Music Lafayette Hall Music East Liberty DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 St. Andrew’s Church 1858 1858 Festival Concert by choral society at St. St. Andrew’s Music Andrew’s Church Church DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Lafayette Hall 2/9/1858 1858 Soiree Musicale in Lafayette Hall Lafayette Hall Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 2/21/1859 1859 Mlle. PiccoloMini Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Grand Concert 186- 1860 The Grand Vocal & InstruMental concert of unknown Music the world-faMed Vienna Lady Orchestra DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 4 Presbyterian Church, East 5/20/186- 1860 Concert in the Presbyterian Church, East Presbyterian Churc Music Liberty Liberty, Charles C. Mellor, conductor h, East Liberty DepartMent: Pittsburgh Music Archive, #41 St. Peter’s Church 6/18/1860 1860 Oratorios - benefit perforMance for St. Peter’s Church Music purchase of organ for St. Mark’s Church in on Grant Street DepartMent: East BirMinghaM Pittsburgh Music Archive, #46 Returned Soldier Boys 1863 1863 Three PrograMs ChathaM and Wylie Music Ministrels Ave. DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 1 Green FaMily Minstrels 12/11/1865 1865 Benefit PrograM AcadeMy of Music Music DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. 1 St. John's Choir 12/30/1865 1865 Benefit PrograM BirMinghaM Town Music Hall, South Side DepartMent: Pittsburgh Concert PrograMs, v. -

Pittsburgh Symphony History

A History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra For more than 120 years, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra has been an essential part of Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape. The symphony, known for its artistic excellence, is credited with a rich history of the world’s finest conductors and musicians, and a strong commitment to the Pittsburgh region and its citizens. This tradition was furthered in fall 2008, when Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck assumed the position of music director with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Honeck will celebrate his 10th anniversary season with the Pittsburgh Symphony in the 2017-2018 season. Heading the list of internationally recognized conductors to have led the Pittsburgh Symphony is Victor Herbert, music director between 1898 and 1904, who influenced the early development of the symphony. Preceding Herbert was Frederic Archer (1896-1899), the first Pittsburgh Orchestra conductor. The orchestra’s solidification as an American institution took place in the late 1930s under the direction of Maestro Otto Klemperer. Conductors prior to Klemperer were Emil Paur (1904-1910), Elias Breeskin (1926-1930) and Antonio Modarelli (1930-1937). From 1938 to 1948, under the dynamic directorship of Fritz Reiner, the Orchestra embarked on a new phase of its history, making its first international tour and its first commercial recording. The orchestra’s standard of excellence was maintained and enhanced through the inspired leadership of William Steinberg during his quarter century as music director between 1952 and 1976. André Previn (1976-1984) led the Orchestra to new heights through tours, recordings and television, including the PBS series, “Previn and the Pittsburgh.” Lorin Maazel began his relationship with the Pittsburgh Symphony in 1984 as music consultant but later served as a highly regarded music director from 1988 to 1996. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1994

Boston Symphony Orchestr S E I J I O Z A W A MUSIC DIRECTOR Tangtewrod THE INTERIOR § ALTERNATIVE The Home Furnishing Center Come Visit The Berkshires Newest Attraction We've QUADRUPLED Our Selling Space BROADENED Our Product Line INCREASED Our Stock Levels But We've Kept The Same LOW PRICES We're Famous For! Fabric, Bedding, Wallpaper, Oriental Carpets, Area Rugs On site sewing for small projects We Feature FAMOUS BRAND Seconds At Tremendous Savings! Mon - Sat 10 - 5 5 Hoosac St. Adams, Ma. (413) 743 - 1986 * 2MI V I j? Seiji Ozawa, Music Director One Hundred and Thirteenth Season, 1993-94 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Nicholas T Zervas, Vice-Chairman and President-elect Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and David B.Arnold, Jr. Deborah B. Davis Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Nina L. Doggett Allen Z. Kluchman Molly Beals Millman James F. Cleary Dean Freed Harvey Chet Mrs. Robert B. Newman - John F. Cogan,Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Krentzman Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Thelma E. Goldberg George Krupp Richard A. Smith William F Connell Julian T Houston R. Willis Leith, Jr. Ray Stata . William M. Crozier, Jr. Trustees Emeriti Veron R. Alden Nelson J. Darling, Jr. Mrs. George I. Mrs. George Lee Philip K.Allen Archie C. Epps Kaplan Sargent Allen G. Barry Mrs. Harris Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Fahnestock Thomas D. Perry, Jr. -

A History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

A History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra For more than 120 years, the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra has been an essential part of Pittsburgh’s cultural landscape. The symphony, known for its artistic excellence, is credited with a rich history of the world’s finest conductors and musicians, and a strong commitment to the Pittsburgh region and its citizens. This tradition was furthered in fall 2008, when Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck assumed the position of Music Director with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Heading the list of internationally recognized conductors to have led the Pittsburgh Symphony is Victor Herbert, music director between 1898 and 1904, who influenced the early development of the symphony. Preceding Herbert was Frederic Archer (1896-1899), the first Pittsburgh Orchestra conductor. The orchestra’s solidification as an American institution took place in the late 1930s under the direction of Maestro Otto Klemperer. Conductors prior to Klemperer were Emil Paur (1904-1910), Elias Breeskin (1926-1930) and Antonio Modarelli (1930-1937). From 1938 to 1948, under the dynamic directorship of Fritz Reiner, the Orchestra embarked on a new phase of its history, making its first international tour and its first commercial recording. The orchestra’s standard of excellence was maintained and enhanced through the inspired leadership of William Steinberg during his quarter century as music director between 1952 and 1976. André Previn (1976-1984) led the Orchestra to new heights through tours, recordings and television, including the PBS series, Previn and the Pittsburgh. Lorin Maazel began his relationship with the Pittsburgh Symphony in 1984 as music consultant but later served as a highly regarded music director from 1988 to 1996.