Census of Octocorallia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) of the Azores (NE Atlantic) with a Nomenclature Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Oceanography and Marine Biology - an Annual Review] R. N](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2073/oceanography-and-marine-biology-an-annual-review-r-n-12073.webp)

[Oceanography and Marine Biology - an Annual Review] R. N

OCEANOGRAPHY and MARINE BIOLOGY AN ANNUAL REVIEW Volume 44 7044_C000.fm Page ii Tuesday, April 25, 2006 1:51 PM OCEANOGRAPHY and MARINE BIOLOGY AN ANNUAL REVIEW Volume 44 Editors R.N. Gibson Scottish Association for Marine Science The Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory Oban, Argyll, Scotland [email protected] R.J.A. Atkinson University Marine Biology Station Millport University of London Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland [email protected] J.D.M. Gordon Scottish Association for Marine Science The Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory Oban, Argyll, Scotland [email protected] Founded by Harold Barnes Boca Raton London New York CRC is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2006 by R.N. Gibson, R.J.A. Atkinson and J.D.M. Gordon CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-8493-7044-2 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-8493-7044-1 (Hardcover) International Standard Serial Number: 0078-3218 This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission, and sources are indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the valid- ity of all materials or for the consequences of their use. -

Octocoral Diversity of Balıkçı Island, the Marmara Sea

J. Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment Vol. 19, No. 1: 46-57 (2013) RESEARCH ARTICLE Octocoral diversity of Balıkçı Island, the Marmara Sea Eda Nur Topçu1,2*, Bayram Öztürk1,2 1Faculty of Fisheries, Istanbul University, Ordu St., No. 200, 34470, Laleli, Istanbul, TURKEY 2Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV), P.O. Box: 10, Beykoz, Istanbul, TURKEY *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract We investigated the octocoral diversity of Balıkçı Island in the Marmara Sea. Three sites were sampled by diving, from 20 to 45 m deep. Nine species were found, two of which are first records for Turkish fauna: Alcyonium coralloides and Paralcyonium spinulosum. Scientific identification of Alcyonium acaule in the Turkish seas was also done for the first time in this study. Key words: Octocoral, soft coral, gorgonian, diversity, Marmara Sea. Introduction The Marmara Sea is a semi-enclosed sea connecting the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the Turkish Straits System, with peculiar oceanographic, ecological and geomorphologic characteristics (Öztürk and Öztürk 1996). The benthic fauna consists of Black Sea species until approximately 20 meters around the Prince Islands area, where Mediterranean species take over due to the two layer stratification in the Marmara Sea. The Sea of Marmara, together with the straits of Istanbul and Çanakkale, serves as an ecological barrier, a biological corridor and an acclimatization zone for the biota of Mediterranean and Black Seas (Öztürk and Öztürk 1996). The Islands in the Sea of Marmara constitute habitats particularly for hard bottom communities of Mediterranean origin. Ten Octocoral species were reported by Demir (1954) from the Marmara Sea but amongst them, Gorgonia flabellum was probably reported by mistake and 46 should not be considered as a valid record from the Sea of Marmara. -

Active and Passive Suspension Feeders in a Coralligenous Community

! Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 1 The importance of benthic suspension feeders in the biogeochemical cycles: active and passive suspension feeders in a coralligenous community PhD THESIS Martina Coppari Barcelona, 2015 Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 2 Photos by: Federico Betti, Georgios Tsounis Design: Antonio Secilla Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 3 The importance of benthic suspension feeders in the biogeochemical cycles: active and passive suspension feeders in a coralligenous community PhD THESIS MARTINA COPPARI Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals PhD Programme in Environmental Science and Technology June 2015 Director de la Tesi Director de la Tesi Dr. Sergio Rossi Dr. Andrea Gori Investigador Investigador Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Universitat de Barcelona Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Departament d’Ecologia • 3 • Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 4 . Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 5 Para los que me han acompañado en este viaje • 5 • Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 6 . Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 7 Resumen 11 Abstract 13 Introduction 15 Chapter 1 Size, spatial and bathymetrical distribution of the ascidian Halocynthia papillosa in Mediterranean coastal bottoms: benthic-pelagic implications 29 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................30 2. Materials -

Slow Population Turnover in the Soft Coral Genera Sinularia and Sarcophyton on Mid- and Outer-Shelf Reefs of the Great Barrier Reef

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 126: 145-152,1995 Published October 5 Mar Ecol Prog Ser l Slow population turnover in the soft coral genera Sinularia and Sarcophyton on mid- and outer-shelf reefs of the Great Barrier Reef Katharina E. Fabricius* Australian Institute of Marine Science, PMB 3, Townsville, Queensland 4810, Australia ABSTRACT: Aspects of the life history of the 2 common soft coral genera Sinularja and Sarcophyton were investigated on 360 individually tagged colonies over 3.5 yr. Measurements included rates of growth, colony fission, mortality, sublethal predation and algae infection, and were carried out at 18 sites on 6 mid- and outer-shelf reefs of the Australian Great Barrier Reef. In both Sinularia and Sarco- phyton, average radial growth was around 0.5 cm yr.', and relative growth rates were size-dependent. In Sinularia, populations changed very slowly over time. Their per capita mortality was low (0.014 yr.') and size-independent, and indicated longevity of the colonies. Colonies with extensions of up to 10 X 10 m potentially could be several hundreds of years old. Mortality was more than compensated for by asexual reproduction through colony fission (0.035 yr.'). In Sarcophyton, mortality was low in colonies larger than 5 cm disk diameter (0.064 yr-l), and significantly higher in newly recruited small colonies (0.88 yr-'). Photographic monitoring of about 500 additional colonies from 16 soft coral genera showed that rates of mortality and recruitment In the family Alcyoniidae differed fundamentally from those of the commonly more 'fugitive' families Xeniidae and Nephtheidae. Rates of recruitment by larval set- tlement were very low in a majority of the soft coral taxa. -

SOUTH AFRICAN ASSOCIATION for MARINE BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Investigational Report No. 68 Corals O

SOUTH AFRICAN ASSOCIATION FOR MARINE BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Investigational Report No. 68 Corals of the South-west Indian Ocean II. Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. (Cnidaria, Alcyonacea) from deep reefs on the KwaZulu-Natal Coast, South Africa by Y. Benayahu and M.H. Sch layer Edited by M.H. Schleyer Published by THE OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.0 Box 10712, Manne Parade 4056 DURBAN SOUTH AFRICA October 1995 Copynori ISBN 0 66989 07« 3 ISSN 0078-320X Frontispiece. Colony of Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. in Its natural habitat with its polyps expanded Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. (Cnidaria, Alcyonacea) from deep reefs on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa by Y. Benayahui and M. H. Schleyeri 'Department of Zoology, George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences. Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel. ^Oceanographic Research Institute, P.O. Box 10712, Marine Parade 4056, Durban, South Africa. ABSTRACT Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. is a new octocoral species (family Alcyoniidae) described from material collected on deep reefs along the coast of KwaZulu- Natal, South Africa. The species has spheroid, radiate and double deltoid sclerites, the latter being the most conspicuous sclerites and aiso the most abundant in the interior of the colony. Keywords: Eleutherobia, Cnidaria, Alcyonacea. Octocorallia, coral reefs, South Africa. INTRODUCTION The alcyonacean fauna of southern Africa (Cnidaria, Octocorallia) has been thoroughly examined and revised by Williams (1992). The tropical coastal area of northern KwaZulu-Natal has recently been investigated at Sodwana Bay and yielded 37 species of the families Tubiporidae. Alcyoniidae and Xeniidae (Benayahu, 1993). Further collections conducted on the deeper reef areas of Two-Mile Reef at Sodwana Bay. -

Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands

国立科博専報,(52), pp. 65–94 , 2018 年 3 月 28 日 Mem. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Tokyo, (52), pp. 65–94, March 28, 2018 Preliminary Report on the Octocorals (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Octocorallia) from the Ogasawara Islands Yukimitsu Imahara1* and Hiroshi Namikawa2 1Wakayama Laboratory, Biological Institute on Kuroshio, 300–11 Kire, Wakayama, Wakayama 640–0351, Japan *E-mail: [email protected] 2Showa Memorial Institute, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–0005, Japan Abstract. Approximately 400 octocoral specimens were collected from the Ogasawara Islands by SCUBA diving during 2013–2016 and by dredging surveys by the R/V Koyo of the Tokyo Met- ropolitan Ogasawara Fisheries Center in 2014 as part of the project “Biological Properties of Bio- diversity Hotspots in Japan” at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Here we report on 52 lots of these octocoral specimens that have been identified to 42 species thus far. The specimens include seven species of three genera in two families of Stolonifera, 25 species of ten genera in two families of Alcyoniina, one species of Scleraxonia, and nine species of four genera in three families of Pennatulacea. Among them, three species of Stolonifera: Clavularia cf. durum Hick- son, C. cf. margaritiferae Thomson & Henderson and C. cf. repens Thomson & Henderson, and five species of Alcyoniina: Lobophytum variatum Tixier-Durivault, L. cf. mirabile Tixier- Durivault, Lohowia koosi Alderslade, Sarcophyton cf. boletiforme Tixier-Durivault and Sinularia linnei Ofwegen, are new to Japan. In particular, Lohowia koosi is the first discovery since the orig- inal description from the east coast of Australia. -

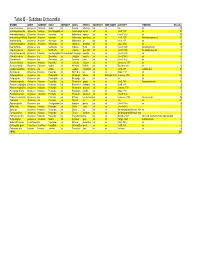

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Author's Accepted Manuscript

Author’s Accepted Manuscript This is the accepted version of the following article: Rakka, M., Bilan, M., Godinho, A., Movilla, J., Orejas, C., & Carreiro-Silva, M. (2019). First description of polyp bailout in cold-water octocorals under aquaria maintenance. Coral Reefs, 38(1), 15-20, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-018-01760- x. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Springer Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions 1 First description of polyp bail-out in cold-water octocorals under aquaria maintenance Maria Rakka1,2,3, Meri Bilan1,2,3, Antonio Godinho1,2,3,Juancho Movilla4,5, Covadonga Orejas4, Marina Carreiro-Silva1,2,3 1 MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre and Centre of the Institute of Marine Research 2 IMAR – University of the Azores, Rua Frederico Machado 4, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal 3 OKEANOS Research Unit, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of the Azores, 9901-862, Horta, Portugal 4 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, Centro Oceanográfico de Baleares, Moll de Ponent s/n, 07015 Palma, Spain 5 Instituto de Ciencias del Mar (ICM-CSIC). Passeig Maritim de la Barceloneta 37-49, 08003 Barcelona, Spain Corresponding author: Maria Rakka, [email protected], +351915407062 2 Abstract Cnidarians, characterized by high levels of plasticity, exhibit remarkable mechanisms to withstand or escape unfavourable conditions including reverse development which describes processes of transformation of adult stages into early developmental stages with higher mobility. Polyp bail-out is a stress-escape response common among scleractinian species, consisting of massive detachment of live polyps and subsequent death of the mother colony. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

Alcyonium Digitatum

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Alcyonium digitatum (Dead Man's Fingers) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Anthozoa (Corals, Sea Pens, Sea Fans, Sea Anemones) Order: Alcyonacea (Soft Corals) Family: Alcyoniidae (Soft Corals) General comments: none No Species Conservation Range Maps Available for Dead Man's Fingers SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: NA High Climate Change Vulnerability: Alcyonium digitatum is highly vulnerable to climate change. Understudied rare taxa: Recently documented or poorly surveyed rare species for which risk of extirpation is potentially high (e.g. few known occurrences) but insufficient data exist to conclusively assess distribution and status. *criteria only qualifies for Priority 3 level SGCN* Notes: Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers: Formation Name Subtidal Macrogroup Name Subtidal Bedrock Bottom Habitat System Name: Erect Epifauna Macrogroup Name Subtidal Coarse Gravel Bottom Habitat System Name: Erect Epifauna Macrogroup Name Subtidal Mud Bottom Habitat System Name: Unvegetated Macrogroup Name Subtidal Sand Bottom Habitat System Name: Unvegetated Stressors Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers: No Stressors Currently Assigned to Dead Man's Fingers or other Priority 3 SGCN. Species Level Conservation Actions Assigned to Dead -

The Genetic Identity of Dinoflagellate Symbionts in Caribbean Octocorals

Coral Reefs (2004) 23: 465-472 DOI 10.1007/S00338-004-0408-8 REPORT Tamar L. Goulet • Mary Alice CofFroth The genetic identity of dinoflagellate symbionts in Caribbean octocorals Received: 2 September 2002 / Accepted: 20 December 2003 / Published online: 29 July 2004 © Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Many cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea Introduction anemones) maintain a symbiosis with dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae). Zooxanthellae are grouped into The cornerstone of the coral reef ecosystem is the sym- clades, with studies focusing on scleractinian corals. biosis between cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea We characterized zooxanthellae in 35 species of Caribbean octocorals. Most Caribbean octocoral spe- anemones) and unicellular dinoñagellates commonly called zooxanthellae. Studies of zooxanthella symbioses cies (88.6%) hosted clade B zooxanthellae, 8.6% have previously been hampered by the difficulty of hosted clade C, and one species (2.9%) hosted clades B and C. Erythropodium caribaeorum harbored clade identifying the algae. Past techniques relied on culturing and/or identifying zooxanthellae based on their free- C and a unique RFLP pattern, which, when se- swimming form (Trench 1997), antigenic features quenced, fell within clade C. Five octocoral species (Kinzie and Chee 1982), and cell architecture (Blank displayed no zooxanthella cladal variation with depth. 1987), among others. These techniques were time-con- Nine of the ten octocoral species sampled throughout suming, required a great deal of expertise, and resulted the Caribbean exhibited no regional zooxanthella cla- in the differentiation of only a small number of zoo- dal differences. The exception, Briareum asbestinum, xanthella species. Molecular techniques amplifying had some colonies from the Dry Tortugas exhibiting zooxanthella DNA encoding for the small and large the E.