The End of an Era in Dutch Shipping – P&O Nedlloyd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shipbreaking Bulletin of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition # 60, from April 1 to June 30, 2020

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 60, from April 1 to June 30, 2020 August 4, 2020 On the Don River (Russia), January 2019. © Nautic/Fleetphoto Maritime acts like a wizzard. Otherwise, how could a Renaissance, built in the ex Tchecoslovakia, committed to Tanzania, ambassador of the Italian and French culture, carrying carefully general cargo on the icy Russian waters, have ended up one year later, under the watch of an Ukrainian classification society, in a Turkish scrapyard to be recycled in saucepans or in containers ? Content Wanted 2 General cargo carrier 12 Car carrier 36 Another river barge on the sea bottom 4 Container ship 18 Dreger / stone carrier 39 The VLOCs' ex VLCCs Flop 5 Ro Ro 26 Offshore service vessel 40 The one that escaped scrapping 6 Heavy load carrier 27 Research vessel 42 Derelict ships (continued) 7 Oil tanker 28 The END: 44 2nd quarter 2020 overview 8 Gas carrier 30 Have your handkerchiefs ready! Ferry 10 Chemical tanker 31 Sources 55 Cruise ship 11 Bulker 32 Robin des Bois - 1 - Shipbreaking # 60 – August 2020 Despina Andrianna. © OD/MarineTraffic Received on June 29, 2020 from Hong Kong (...) Our firm, (...) provides senior secured loans to shipowners across the globe. We are writing to enquire about vessel details in your shipbreaking publication #58 available online: http://robindesbois.org/wp-content/uploads/shipbreaking58.pdf. In particular we had questions on two vessels: Despinna Adrianna (Page 41) · We understand it was renamed to ZARA and re-flagged to Comoros · According -

Post 9/11 Maritime Security Measures : Global Maritime Security Versus Facilitation of Global Maritime Trade Norhasliza Mat Salleh World Maritime University

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 2006 Post 9/11 maritime security measures : global maritime security versus facilitation of global maritime trade Norhasliza Mat Salleh World Maritime University Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mat Salleh, Norhasliza, "Post 9/11 maritime security measures : global maritime security versus facilitation of global maritime trade" (2006). World Maritime University Dissertations. 98. http://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/98 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden POST 9/11 MARITIME SECURITY MEASURES: Global Maritime Security versus the Facilitation of Global Maritime Trade By NORHASLIZA MAT SALLEH Malaysia A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of MASTERS OF SCIENCE in MARITIME AFFAIRS (MARITIME ADMINISTRATION) 2006 © Copyright Norhasliza MAT SALLEH, 2006 DECLARATION I certify that all material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me. The content of this dissertation reflect my own personal views, and are not necessarily endorsed by the University. Signature : …………………………… Date : ……………………………. Supervised by: Cdr. -

P&O Nedlloyd Genoa

Report on the investigation of the loss of cargo containers overboard from P&O Nedlloyd Genoa North Atlantic Ocean on 27 January 2006 Marine Accident Investigation Branch Carlton House Carlton Place Southampton United Kingdom SO15 2DZ Report No 20/2006 August 2006 Extract from The United Kingdom Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 – Regulation 5: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident under the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005 shall be the prevention of future accidents through the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances. It shall not be the purpose of an investigation to determine liability nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve its objective, to apportion blame.” NOTE This report is not written with litigation in mind and, pursuant to Regulation 13(9) of the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2005, shall be inadmissible in any judicial proceedings whose purpose, or one of whose purposes is to attribute or apportion li ability or blame. Further printed copies can be obtained via our postal address, or alternatively by: Email: [email protected] Tel: 023 8039 5500 Fax: 023 8023 2459 All reports can also be found at our website: www.maib.gov.uk CONTENTS Page GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS SYNOPSIS 1 SECTION 1 - FACTUAL INFORMATION 3 1.1 Particulars of P&O Nedlloyd Genoa and accident 3 1.2 Narrative 5 1.2.1 Time zones 5 1.2.2 Schedule 5 1.2.3 Passage plan 5 1.2.4 The passage 6 1.2.5 Post -

INDONESIA NEW ACQUISITIONS Additions to Our Catalogues

GERT JAN BESTEBREURTJE Rare Books Langendijk 8, 4132 AK Vianen The Netherlands Telephone +31 - (0)347 - 322548 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our Web-page at http://www.gertjanbestebreurtje.com LIST 70 – INDONESIA NEW ACQUISITIONS Additions to our catalogues 173: INDONESIA - Including books from the library of professor Teuku Iskandar - please click HERE 175: Urban culture in S.E. Asia – Batavia, Singapore, Hong Kong. - please click HERE 1 ATLAS VAN TROPISCH NEDERLAND. Uitgegeven door het Nederlandsch Aardrijkskundig Genootschap in samenwerking met den Topografischen Dienst in Nederlandsch-Indië. (Batavia, Amsterdam), 1938. Large folio. Original green cloth with gilt lettering. With 31 double-page coloured maps, and register (17) pp. € 95,00 First edition. - Still the best and only scientific atlas of the Dutch East Indies and the Dutch territories of the Antilles and Suriname. 'For its time, an unparelleled atlas of a colonial empire, highly praised for its cartographic standard. The maps were drawn by the cartographers of the Topographical Survey at Batavia. In its final stage of preparation, the supervision was with Dr. A.J. Pannekoek' (Koeman VI, p.189). 2 BOROBUDUR. Kunst en religie in het oude Java. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, 1977. Folio. Wrappers. With many illustrations (several in colours). 194 pp. € 20,00 3 BUDAYA INDONESIA. Arts and crafts in Indonesia. Kunst en cultuur in Indonesië. Amsterdam, Tropenmuseum, 1987. 4to. Wrappers. With many illustrations (several in colours). 284 pp. € 35,00 € 35,00 Deals with the various cultural influences on Indonesian crafts from prehistoric times to the present, based on the Tropenmuseum`s collection. 4 CORPUS DIPLOMATICUM NEERLANDA-INDICUM. -

SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date Examplesshsa Line

Brochure Inventory - SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date ExampleSSHSA line A1 Adelaide S.S. Co. Moonta Admiral, Azure Seas, Emerald Seas, A1 Admiral Cruises, Inc. Stardancer 1960-1992 Enotria, Illiria, San Giorgio, San Marco, Ausonia, Esperia, Bernina,Stelvio, Brennero, Barletta, Messsapia, Grimani,Abbazia, S.S. Campidoglio, Espresso Cagliari, Espresso A1 Adriatica Livorno, corriere del est,del sud,del ovest 1949-1985 A1 Afroessa Lines Paloma, Silver Paloma 1989-1990 Alberni Marine A1 Transportation Lady Rose 1982 A1 Airline: Alitalia Navarino 1981 Airline: American A1 Airlines (AA) Volendam, Fairsea, Ambassador, Adventurer 1974 Bahama Star, Emerald Seas, Flavia, Stweard, Skyward, Southward, Federico C, Carla C, Boheme, Italia, Angelina Lauro, Sea A1 Airline: Delta Venture, Mardi Gras 1974 Michelangelo, Raffaello, Andrea, Franca C, Illiria, Fiorita, Romanza, Regina Prima, Ausonia, San Marco, San Giorgio, Olympia, Messapia, Enotria, Enricco C, Dana Corona, A1 Airline: Pan Am Dana Sirena, Regina Magna, Andrea C 1974 A1 Alaska Cruises Glacier Queen, Yukon Star, Coquitlam 1957-1962 Aleutian, Alaska, Yukon, Northwestern, A1 Alaska Steamship Co. Victoria, Alameda 1930-1941 A1 Alaska Ferry Malaspina, Taku, Matanuska, Wickersham 1963-1989 Cavalier, Clipper, Corsair, Leader, Sentinel, Prospector, Birgitte, Hanne, Rikke, Susanne, Partner, Pegasus, Pilgrim, Pointer, Polaris, Patriot, Pennant, Pioneer, Planter, Puritan, Ranger, Roamer, Runner Acadia, Saint John, Kirsten, Elin Horn, Mette Skou, Sygna, A1 Alcoa Steamship Co. Ferncape, -

Merger Decision IV/M.831 of 19.12.1996

EN Case No IV/M.831 - P&O / ROYAL NEDLLOYD Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 19/12/1996 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 396M0831 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 19.12.1996 PUBLIC VERSION MERGER PROCEDURE ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION To the notifying parties Dear Sirs, Subject : Case No IV/M.831 - P&O/Nedlloyd Notification of 19 November 1996 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation N 4064/89 1. On 19 November 1996 the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Co (United Kingdom) ("P&O") and Royal Nedlloyd NV (Netherlands) ("Nedlloyd") notified to the Commission an intended operation whereby they acquire within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of Council Regulation (EEC) N 4064/89 (the "Merger Regulation") joint control of P&O Nedlloyd Container Line Ltd (United Kingdom) ("P&O Nedlloyd"). I THE PARTIES 2. P&O engages in a broad range of activities, including passenger and cargo shipping, integrated transportation and warehousing. 3. Nedlloyd is an international logistics services company whose core activities are container logistics through a network of global shipping links; and transport, forwarding, stock management and distribution, primarily in Europe. 4. The activities of both P&O and Nedlloyd include ocean container shipping and related landside activities. Rue de la Loi 200 - B-1049 Brussels - Belgium Telephone: exchange (+32-2)299.11.11 Telex: COMEU B 21877 - Telegraphic address: COMEUR Brussels - 2 - II THE OPERATION (i) Introduction 5. -

Shipbreaking Bulletin of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition # 44, from April 1 to June 30, 2016

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 44, from April 1 to June 30, 2016 July 29, 2016 Content Panama Papers in the troubled waters 1 Offshore (platforms, research, 15 Container ship 44 of shipbreaking drilling, supply vessel) Ro Ro 59 Brest : it is no more fun for the sea 3 Tug 20 Car carrier 60 Defense Secret aboard the Colbert 3 Dredger 21 Bulk carrier 62 A not-protected species threatened 4 Ferry 23 Reefer 86 by extinction in Canada Passenger ship 25 The End : Kapetan Christos, 87 Military and auxiliary vessels 6 Tanker 26 ex Marie Aude, a star leaves News from the severely injured ones 10 Chemical tanker 28 the sea Overview: April-May-June 2016 12 Gas carrier 28 Post 2000 are to be scrapped 14 General cargo 32 Sources 90 Panama Papers in the troubled waters of shipbreaking Shipbreaking goes through the from now on celebrated Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. To go from beaching’s hell to a tax haven you have to pass through the Urizen Shipping box, care of Mossack Fonseca & Co (Bvi) Ltd, Road Town, Tortola, capital city of the British Virgin Islands. Moved in the Caribbean, money is on the whole secure from curious inquisiters and tax collectors. 5 ships to be broken up by European and Russian owners were beached in Alang or Chittagong under the title of Urizen Shipping, the subsidiary of Mossack Fonseca. For the last voyage, the 5 merchant ships have been deflagged and were under the protection of Tuvalu and Niue, two Pacific micro-States. -

P&O Nedlloyd Los Angeles

P&O NEDLLOYD LOS ANGELES IMO No: 7811484 CONTAINER 1980 / 30175 GT COMPANY: YARD INFORMATION: SCRAPPING INFORMATION: P&O Nedlloyd B.V., Van Der Giessen-de Noord 917 Alang 22/7/2009 Netherlands Krimpen a/d Ijssel (Netherlands) © A. Calvert GENERAL INFORMATION: OWNER & FLAG HISTORY: IMO number: 7811484 MSC TOGO 23-10-2006 LRF 1st name: ZEELANDIA VUNGTAU 02-10-2006 LRF flag / nationality: Netherlands MAERSK VUNGTAU 05-12-2005 LRF owner: Costamare Shipping P&O NEDLLOYD LOS ANGELES 12-05-2000 LRF operator: MSC Flag Date of record Source completion year: 1980 Liberia 02-10-2006 LRF shipyard: Van Der Giessen-de Noord N.V., Netherlands Netherlands 06-11-2003 LRF yard / hull number: 917 Bahamas 04-09-2001 LRF engine design: SUL Netherlands 12-05-2000 LRF engine type: 10RND90M Registered owner Date of record Source power output (KW): 22169 RONDA SHIPPING CO since 05-07-2008 LRF maximum speed (Kn): 21,3 PRINCIPE NAVIGATION SA 02-10-2006 LRF overall length (m): 209,00 P&O NEDLLOYD BV 01-02-2005 LRF overall beam (m): 31,00 P&O NEDLLOYD LIJNEN 04-09-2001 LRF maximum draught (m): 10,20 P&O NEDLLOYD BV 01-01-1998 LRF maximum TEU capacity: 1460 Ship manager Date of record Source container capacity at 14t (TEU): CIEL SHIPMANAGEMENT 02-10-2006 LRF reefer containers (TEU): 366 BLUE STAR SHIP MANAGEMENT BV 07-02-2005 LRF deadweight (ton): 23.678 P&O NEDLLOYD BV 01-01-1997 LRF gross tonnage (ton): 30.175 handling gear: None http://www.containership-info.com SALES, TRANSFERS & RENAMINGS: ZEELANDIA 1980-80 name when launched BENATTOW 1980-82 NEDLLOYD ZEELANDIA 1982-83 JAVA WINDS 1983-84 ZEELANDIA 1984-86 NEDLLOYD ZEELANDIA 1986-98 KHL-Lijnen B.V., Netherlands P&O NEDLLOYD LOS ANGELES 1998-05 P&O Nedlloyd B.V., Netherlands MAERSK VUNGTAU 2005-06 P&O Nedlloyd B.V., Netherlands VUNGTAU 2006-06 Principe Navigation S.A., Liberia MSC TOGO 2006-09 Ronda Shg. -

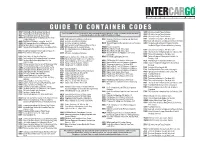

GUIDE to CONTAINER CODES ACTU P&O Nedlloyd BV, Rotterdam

GUIDE TO CONTAINER CODES ACTU P&O Nedlloyd BV, Rotterdam. Netherlands SCDU GE SeaCo, George Town, Barbados AJCU P&O Nedlloyd BV, Rotterdam, Netherlands The following list is not intended to be comprehensive but relates to those containers which are most SCXU GE SeaCo, George Town, Barbados frequently mentioned in the LLDCN Container listings. South East & AKLU Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd, Tokyo, Japan SCZU GE SeaCo, George Town, Barbados AMSU Malaysian International Shipping Corp Bhd, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia GCDU P&O Nedlloyd BV, Rotterdam, Netherlands MISU Malaysian International Shipping Corp Bhd, Kuala SISU Transmaerica Leasing Inc, Purchase, USA AMZU Amphibious Container Leasing Ltd, Fleet, UK GCEU GE SeaCo, Georgetown, Barbados Lumpur, Malaysia SNTU Stolt Tank Containers Leasing Ltd, Hamilton, Bermuda ANNU ANL Container Line Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia GESU GE Seaco, Georgetown, Barbados MLCU Textainer Equipment Management Ltd, San Francisco, SUDU Hamburg-Sudamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts- APMU Ap Moller Maersk, Copenhagen, Denmark GLDU Gold Container Corp, Puteaux La Defense, France USA Gesellschaft Eggert & Amsinck, Hamburg, Germany AZLU Australia New Zealand Direct Line, Long Beach, USA GMEU Wilhelmsen Lines AS, Lysaker, Norway MMMU Fesco Lines Australia GSLU Zim Israel Navigation Co (as lease-holder), Tel MOGU Mitsui-OSK Lines Ltd, Tokyo, Japan TCSU Transamerica Leasing Inc, Purchase, USA BHCU Bridgehead Container Services Ltd, Liverpool, UK MOLU Mitsui-OSK Lines Ltd, Tokyo, Japan Aviv, Israel TCKU Triton Container International -

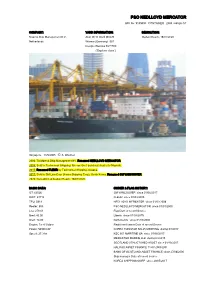

P&O Nedlloyd Mercator

P&O NEDLLOYD MERCATOR IMO No: 9189495 CONTAINER 2000 / 66526 GT COMPANY: YARD INFORMATION: DEMOLITION: Maersk Ship Management B.V., Aker MTW Werft GmbH Gadani Beach, 16/07/2020 Netherlands Wismar (Germany) 001 Design: Warnow CV 5500 (“Explorer class“) Singapore 13/9/2005 S. Wiedner 2006: To Maersk Ship Management BV. Renamed NEDLLOYD MERCATOR. 2008: Sold to Technomar Shipping, Greece (incl. bareboat charter to Maersk). 2015: Renamed FLEUR by Technomar Shipping, Greece. 2017: Sold to SM Line Corp (Korea Shipping Corp), South Korea. Renamed SM VANCOUVER. 2020: Demolition at Gadani Beach, 16/07/2020. BASIC DATA: OWNER & FLAG HISTORY: GT: 66526 SM VANCOUVER since 01/06/2017 DWT: 67712 FLEUR since 01/03/2015 TEU: 5618 NEDLLOYD MERCATOR since 01/02/2006 Reefer: 500 P&O NEDLLOYD MERCATOR since 01/01/2000 Loa: 278.01 Flag Date of record Source Bmd: 40.00 Liberia since 01/03/2015 Draft: 14.00 Netherlands since 01/03/2000 Engine: 1x oil Sulzer Registered owner Date of record Source Power: 54900 kW KOREA TONNAGE NO 25 SHIPPING during 07/2017 Speed: 25.3 kn KSC 601 MARITIME SA since 01/06/2017 MERCATOR MARINE LLC during 03/2015 SCOTLAND STRUCTURED ASSET since 01/10/2007 HALIFAX ASSET FINANCE 11-07-2000 LRF BANK OF SCOTLAND ASSET FINANCE since 27/06/2000 Ship manager Date of record Source KOREA SHIPPING CORP since 29/05/2017 KLC SM CO LTD since 29/05/2017 TECHNOMAR SHIPPING INC during 03/2015 MAERSK LINE A/S since 01/02/2015 MAERSK CO LTD during 08/2010 MOLLER-MAERSK A/S since 20/09/2008 MAERSK SHIP MANAGEMENT BV since 02/02/2005 P&O NEDLLOYD BV 11-07-2000 LRF EX-NAMES: P&O NEDLLOYD MERCATOR 2000-06 Bank of Scotland Structural Asset Finance Ltd, Netherlands NEDLLOYD MERCATOR 2006-15 Bank of Scotland Structured Asset Finance Ltd, Netherlands FLEUR 2015-17 Mercator Marine LLC, Liberia SM VANCOUVER 2017-17 KSC 601 Maritime SA, Liberia SM VANCOUVER 2017-20 Korea Tonnage No. -

Blue Denmark Versus the Dutch Maritime Network

Paper prepared for the 12th Annual Conference of the European Business History Association on TRANSACTIONS AND INTERACTIONS - THE FLOW OF GOODS, SERVICES, AND INFORMATION Bergen, Norway, August 20-23, 2008 THE BLUE DENMARK VERSUS THE DUTCH MARITIME CLUSTER: A FRAMEWORK FOR COMPARING (SIMILAR) CLUSTERS IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES Henrik Sornn-Friese Associate Professor, Department for Innovation and Organizational Economics, DRUID Copenhagen Business School, Kilevej 14A, DK-2000 Frederiksberg, DENMARK Phone: (+ 45) 3815 2932, Fax: (+ 45) 3815 2540, [email protected] 25 June 2008 FIRST DRAFT, PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE Abstract The industry cluster approach has become the cornerstone in European maritime policy, with important work being carried out by the European Commission, national governments, maritime authorities, key maritime organizations and even individual firms. It has become the main maritime policy tool in many member states and an important part of maritime policies in other parts of the world. Recently, there have been enquiries to promote a “continent wide cluster” view on the European maritime industry and efforts at defining a “European Maritime Cluster”, which is seen as important for economic development (competitiveness, innovation and growth) as well as for encountering the potential social and environmental hazards related to the maritime industry. Through a comparative-historical case study of the maritime clusters in Denmark and the Netherlands the present paper argues that a focus on a “continent wide” or “European” maritime cluster is problematic, since with overly broad conceptualizations we miss out on a range of important subtleties and dynamics taking place at less aggregate spatial levels. As such, “the European maritime cluster” might be an analytically useful umbrella concept at best. -

P&O Nedlloyd Southampton

P&O NEDLLOYD SOUTHAMPTON IMO No: 9153850 CONTAINER 1998 / 80942 GT COMPANY: YARD INFORMATION: SCRAPPING INFORMATION: P&O Nedlloyd B.V., Ishikawajima H.I. 3088 Netherlands Kure (Japan) Hamburg 1/9/1998 © S. Wiedner North Sea 15/5/2009 © S. Wiedner collection GENERAL INFORMATION: OWNER & FLAG HISTORY: IMO number: 9153850 MAERSK KIEL 27-02-2006 LRF yard: Ishikawajima Heavy Industries, Kure P&O NEDLLOYD SOUTHAMPTON 12-05-2000 LRF yard number: 3088 Flag Date of record Source year of building: 1998 United Kingdom 12-05-2000 LRF Length: 299.90 m Registered owner Date of record Source Width: 42.83 m CARAVANS INTERNATIONAL 17-05-2004 LRF Depth: 24.40 m CAPITAL BANK LEASING 3 31-03-1998 LRF gross tonnage: 80942 Ship manager Date of record Source deadweight: 88699 BLUE STAR SHIP MANAGEMENT BV 07-02-2005 LRF Capacity: 6690 teu P&O NEDLLOYD BV 25-04-2000 LRF Reefer capacity: 710 teu P&O NEDLLOYD LTD 31-03-1998 LRF max. speed: 24.5 knots SALES, TRANSFERS & RENAMINGS: P&O NEDLLOYD SOUTHAMPTON 1998-06 Capital Bank Leasing 3 Ltd., U.K. MAERSK KIEL 2006- Caravans International Finance Ltd., U.K. GENERAL VESSEL INFORMATION: The P&O NEDLLOYD SOUTHAMPTON class employ the worlds most powerful marine diesel engines to give a loaded service speed of 24.5 knots. The vessels are 80942 GT and their container capacity is 6690 teu. They are capable of making the Japan- Europe voyage in about 24 days. Report by Marine News Sailing route 2005 on P&O Nedlloyd Loop7 Service Rotterdam - Hamburg - Gioia Tauro - Singapore - Kaohsiung - Pusan - Dalian - Tjanjin -Qingang - Qingdao - Pusan - Ningbo - Kaohsiung - Singapore - Port Kelang - Southampton - Rotterdam www.containershipregister.nl - 15 February 2005 P&O NEDLLOYD SOUTHAMPTON 9153850, 4-1998 opgeleverd door Ishikawajima Harima Heavy Industries Co.