Regreening the Sahel a Quiet Agroecological Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGREENING: SIX STEPS to SUCCESS a Practical Approach to Forest and Landscape Restoration

SCALING UP REGREENING: SIX STEPS TO SUCCESS A Practical Approach to Forest and Landscape Restoration CHRIS REIJ AND ROBERT WINTERBOTTOM WRI.ORG Scaling Up Regreening i Design and layout by: Carni Klirs [email protected] Bill Dugan [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword 3 Executive Summary 9 Part I. Introduction 13 Part II. How and Where is Regreening Happening? 21 Part III. The Impacts Of Regreening 33 Part IV. The Six Steps of Scaling Up Regreening 35 Step 1. Identify and Analyze Existing Regreening Successes 36 Step 2. Build a Grassroots Movement for Regreening 40 Step 3. Address Policy and Legal Issues and Improve Enabling Conditions for Regreening 45 Step 4. Develop and Implement a Communication Strategy 49 Step 5. Develop or Strengthen Agroforestry Value Chains And Capitalize on the Role of the Market in Scaling Up Regreening 51 Step 6. Expand Research Activities to Fill Gaps in Knowledge About Regreening 53 Part V. Concluding Thoughts 63 References 65 Endnotes iv WRI.org FOREWORD In September 2014, the New York Declaration farmers to facilitate and accelerate their regreening on Forests was formulated and signed during the practices at scale and identifies barriers that need to UN Climate Summit. Signatories—governments, be overcome. It provides guidance for development corporations, indigenous peoples’ groups, and practitioners seeking to scale up regreening through CSOs—pledged to restore 350 million hectares targeted and cost-effective interventions, and to of degraded forestland by 2030. This historic policymakers and others in a position to mobilize commitment can be achieved only if the pace of resources and improve the enabling conditions for forest regeneration is sharply accelerated. -

The Interaction Between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso - an Example from Yaho

The Interaction between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso - An example from Yaho Malin Gustafsson Lina Norman Lunds universitet Lunds tekniska högskola Fastighetsvetenskap Lund University Lund Institute of Technology Real Estate Science The Interaction between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso ___________________________________________________________ The Interaction between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso - An example from Yaho Master of Science Thesis by: Malin Gustafsson Lina Norman Supervisor: Klas Ernald Borges Local Supervisor: Zounkata Tuina Examiner: Ulf Jensen Department of Real Estate Science Lund Institute of Technology Lund University Hämtställe 7 Box 118 221 00 LUND Sweden ISRN/LUTVDG/TVLM 08/5167 SE 1 The Interaction between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso ___________________________________________________________ 2 The Interaction between National Forest Management and Rural Life in Burkina Faso ___________________________________________________________ Preface The ideas for this thesis started over a year ago and we would not have come this far without all the assistance we got from our supervisor Klas Ernald Borges, PhD in Real Estate Planning. A lot of the contacts, information about Burkina Faso and support were given to us by Anders Andén and Olle Wendt who are friends with our supervisor in Yaho. The major part of the work on this thesis has been performed in Burkina Faso and in the village Yaho. We are very grateful that we were given the opportunity to combine studies with getting to know the friendly and generous Burkinabé and their country. The Mayor of Yaho as well our local supervisor Zounkata Tuina has been encouraging in our work and arranged all practicalities whenever needed. -

The Great Green Wall

THE GREATGREAT GREENGREEN WALL WALL HOPE FOR FOR THE THE SAHARA SAHARA AND AND THE THE SAHEL SAHEL 1 FOREWORD BY HER EXCELLENCY TUMUSIIME Rhoda Peace (MS.), COMMISSIONER, DEpartMENT OF RURAL EconoMY AND AGRICUltURE OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION The Great Green Wall for the Sahara and the Sahel Initiative, launched in June 2005 in Ouagadougou, during the 7th summit of the leaders and Heads of State of CEN-SAD (Community of Sahel-Saharan States) by former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, strongly supported by the Senegalese President, was formally adopted at the Conference of Heads of State and Government of the African Union in January 2007. This huge African initiative carries a real message of hope for improving the living conditions of local populations on the long term to live on their land thanks to their own labor, by increasing their incomes and ensuring their food security. Initially, designed around a mosaic of sustainable land management interventions and uses, from Dakar to Djibouti, the Great Green Wall is today recognized internationally as a huge African initiative, supported by all the international institutions working to preserve the environment. Much has been done and much remains to be done! In total, since the launch of the initiative, more than 8 billion dollars have been mobilized and/or promised to support the Great Green Wall. Delivering on all of the Great Green Wall promises requires significant investment such as continued political commitment in all countries, resource mobilization, capacity building and support to local communities. It is also to monitor and coordinate, in the Great Green Wall area, all current and future activities in terms of sustainable land management, adaptation to climate change, sustainable and resilient agriculture.. -

Dryland Restoration Successes in the Sahel and Greater Horn of Africa

Dryland restoration successes in the Sahel and Greater Horn of Africa show how to increase scale and impact Chris Reij, Nick Pasiecznik, Salima Mahamoudou, Habtemariam Kassa, Robert Winterbottom & John Livingstone Farmer managed natural regeneration around Rissiam village, Burkina Faso. Photo: Gray Tappan Introduction Drylands occupy more than 40% of the world’s land area and are home to some two billion people. This includes a disproportionate number of the world’s poorest people, who live in degraded and severely degraded landscapes. The United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification states on its website that 12 million hectares are lost annually to desertification and drought, and that more than 1.5 billion people are directly dependent on land that is being degraded, leading to US$42 billion in lost earnings each year. In Africa, three million hectares of forest are lost annually, along with an estimated 3% of GDP, through depleted soils. The result is that two-thirds of Africa’s forests, farmlands and pastures are now degraded. This means that millions of Africans have to live with malnutrition and poverty, and in the absence of options this further forces the poor to overexploit their natural resources to survive. This in turn intensifies the effects of climate change and hinders economic devel- opment, threatening ecological functions that are vital to national economies. Chris Reij, Senior fellow, World Resources Institute (WRI), Washington DC, USA; Nick Pasiecznik, Dryland restoration coordi- nator, Tropenbos International (TBI), Wageningen, the Netherlands; Salima Mahamoudou, Research associate, World Re- sources Institute (WRI), Washington DC, USA, Habtemariam Kassa, Senior scientist, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Robert Winterbottom, Fellow, Global EverGreening Alliance (GEA), Stoddard, USA; and John Livingstone, Regional policy and research officer, Pastoral and Environmental Network in the Horn of Africa (PENHA), Hargeisa, Somaliland. -

The Best Strategy for Using Trees to Improve Climate and Ecosystems?

NEWS FEATURE NEWS FEATURE The best strategy for using trees to improve climate and ecosystems? Go natural Despite big headlines and big money devoted to massive tree-planting projects that pledge to stave off desertification, the most effective method may be nurturing native seeds, rootstocks, and trees. John Carey, Science Writer Near the start of the rainy season in June 1983, Tony A man of deep faith, Rinaudo asked God for Rinaudo hauled a load of trees in his truck to be guidance. In a moment of clarity, his eye caught sight planted in remote villages in the Maradi region of of one of the bushes. At closer look, he realized that Niger. Driving onto sandy soil, Rinaudo stopped to let it was no mere bush or weed; instead, it was a poten- air out of his tires to get better traction, and was hit by tially valuable native tree—if permitted to grow. There a sense of futility. For years, the Australian missionary was no need to plant trees; they were already there. had been working to improve the lives of people in one “At that moment everything changed,” he says. Even of the poorest countries in Africa by planting trees. But it a seeming desert harbors tree stumps, roots, and wasn’t working. Most of the trees died or were pulled out seeds that can be encouraged and nurtured—“a trea- by farmers. Standing beside his truck, all he could see sure chest waiting to be released,” says Rinaudo. “And was dusty barren plain, broken by a few scraggly bushes. -

Vegetable Gardening in Burkina Faso: Drip Irrigation And

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 12 | Issue 1 Gross, B. and Jaubert, R. 2019. Vegetable gardening in Burkina Faso: Drip irrigation, agroecological farming and the diversity of smallholders. Water Alternatives 12(1): 46-67 Vegetable Gardening in Burkina Faso: Drip Irrigation, Agroecological Farming and the Diversity of Smallholders Basile Gross Institute of Geography and Sustainability, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] Ronald Jaubert Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Small-scale irrigated vegetable production has expanded dramatically in Burkina Faso. Its development can be divided into four periods: the colonial period with the construction of small dams; the boom in reservoir development as a response to drought and famine; the period during which private irrigation was supported; and the current period of new irrigation technologies such as drip irrigation and, to a lesser extent, agroecological vegetable gardening. Since the 1990s, vegetable gardening projects have had a limited impact and irrigation development has been led and financed mainly by farmers. This situation still prevails with current projects, which throws into question their capacity to respond to the needs of family farms. This issue is addressed in the Réo area, where an in-depth survey of family farms revealed a large diversity of situations and livelihood strategies. It became evident from the study that drip irrigation or agroecological gardening can only be adopted by a very small number of family farms. In addressing the problems of smallholders in this regard, development organisations and public policies need to consider their diversity, and adapt accordingly to farming families’ needs and capacities. -

Improving Land and Water Management

Working Paper Installment 4 of “Creating a Sustainable Food Future” IMPROVING LAND AND WATER MANAGEMENT ROBERT WINTERBOTTOM, CHRIS REIJ, DENNIS GARRITY, JERRY GLOVER, DEBBIE HELLUMS, MIKE MCGAHUEY, AND SARA SCHERR SUMMARY The world’s food production systems face enormous CONTENTS challenges. Millions of farmers in developing countries Summary ......................................................................1 are struggling to feed their families as they contend Land, Water, and Food ..................................................3 with land degradation, land use pressures, and climate change. Many smallholder farmers must deal with low and Land Degradation Challenges .......................................6 unpredictable crop yields and incomes, as well as chronic Improved Land and Water food insecurity. These challenges are particularly acute in Management Practices ................................................11 Sub-Saharan Africa’s drylands, where land degradation, Opportunities for Scaling Up .......................................25 depleted soil fertility, water stress, and high costs for Recommended Approaches fertilizers contribute to low crop yields and associated poverty and hunger. to Accelerate Scaling Up .............................................27 A Call to Action ...........................................................34 Farmers and scientists have identified a wide range of Endnotes .....................................................................36 land and water management practices that can address -

Bottom-Up Perspectives on the Re-Greening of the Sahel

land Article Bottom-Up Perspectives on the Re-Greening of the Sahel: An Evaluation of the Spatial Relationship between Soil and Water Conservation (SWC) and Tree-Cover in Burkina Faso Colin Thor West 1,*, Sarah Benecky 2, Cassandra Karlsson 3, Bella Reiss 4 and Aaron J. Moody 5 1 Department of Anthropology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 3115, USA 2 Law School, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 3380, USA; [email protected] 3 Botany Department, Lund University, 221 00 Lund, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Annunciation House, El Paso, TX 79901, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Geography, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 3220, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 May 2020; Accepted: 23 June 2020; Published: 26 June 2020 Abstract: The Re-Greening of the West African Sahel has attracted great interdisciplinary interest since it was originally detected in the mid-2000s. Studies have investigated vegetation patterns at regional scales using a time series of coarse resolution remote sensing analyses. Fewer have attempted to explain the processes behind these patterns at local scales. This research investigates bottom-up processes driving Sahelian greening in the northern Central Plateau of Burkina Faso—a region recognized as a greening hot spot. The objective was to understand the relationship between soil and water conservation (SWC) measures and the presence of trees through a comparative case study of three village terroirs, which have been the site of long-term human ecology fieldwork. Research specifically tests the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between SWC and tree cover. -

Agroenvironmental Transformation in the Sahel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics IFPRI Discussion Paper 00914 November 2009 Agroenvironmental Transformation in the Sahel Another Kind of “Green Revolution” Chris Reij Gray Tappan Melinda Smale 2020 Vision Initiative This paper has been prepared for the project on Millions Fed: Proven Successes in Agricultural Development (www.ifpri.org/millionsfed) INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) was established in 1975. IFPRI is one of 15 agricultural research centers that receive principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). FINANCIAL CONTRIBUTORS AND PARTNERS IFPRI’s research, capacity strengthening, and communications work is made possible by its financial contributors and partners. IFPRI receives its principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). IFPRI gratefully acknowledges the generous unrestricted funding from Australia, Canada, China, Finland, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, and World Bank. MILLIONS FED “Millions Fed: Proven Successes in Agricultural Development” is a project led by IFPRI and its 2020 Vision Initiative to identify interventions in agricultural development that have substantially reduced hunger and poverty; to document evidence about where, when, and why these interventions succeeded; to learn about the key drivers and factors underlying success; and to share lessons to help inform better policy and investment decisions in the future. -

2018 Annual Report

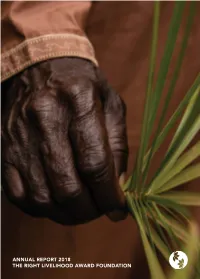

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 THE RIGHT LIVELIHOOD AWARD FOUNDATION Santa Cruz Córdoba Contents Valdivia ABOUT THE FOUNDATION 04 The Right Livelihood Award Foundation 06 The Year at a Glance 08 Governance HONOUR EDUCATE 09 Selecting the Laureates 32 Right Livelihood College 10 2018 Laureates 18 Award Presentation INFORM 20 Award Week: Stockholm & Beyond SUPPORT 34 Increasing Media Visibility 24 Our Promise: Long-term Support FINANCES 26 Protection & Advocacy 28 Synergies for Impact 36 Financial Report 30 North American Laureates’ Conference 38 Expenditure in 2018 Cover: Close-up of Yacouba Sawadogo’s hand, photo © Sophie Garcia 3 Lund Stockholm London Berlin Bonn Zurich Geneva Mumbai Bangkok Port Harcourt Addis Ababa Right Livelihood Offices Press Consultants Right Livelihood College Campuses Swiss Support Foundation ABOUT THE FOUNDATION About the Right Livelihood Award Foundation The Right Livelihood Award Foundation is a non-profit organisation registered in Sweden. Its head office is located in Stockholm, with a branch office in Geneva. The Right Livelihood Award, established in 1980 and widely known as ‘the Alternative Nobel Prize’, is annually presented in Stockholm to four Laureates. Unlike most other international prizes, it has no categories. The Foundation recognises that, in striving to meet the human challenges of today’s world, the most inspiring and remarkable work often defies standard classification. The total prize money in 2018 was SEK 3 million. Anyone can propose candidates to be considered for the Award. After careful investigation by the Foundation’s research team, an international Jury meets to select the recipients. The Foundation provides its Laureates with long-term support and helps them amplify the impact of their work. -

Dirt Dialogues – an Exercise in Transdisciplinary Integration

Andrea von Braun Stiftung voneinander wissen Dirt Dialogues – An Exercise in Transdisciplinary Integration Autorin: Alexandra R. Toland, Institute for Ecology, Technische Universität Berlin / Projekt: Dirt Dialogues – An Exercise in Transdisciplinary Integration / Art des Projektes: Dissertation 1 Andrea von Braun Stiftung voneinander wissen A poster exhibition of artists’ works and a film program was realized from June 8 to June 13, 2014 at the 20th World Congress of Soil Science, (20WCSS) in Jeju, Korea as an empirical exercise in transdisciplinary integration. By integrating the arts into one of the largest and most prominent scientific conferences on soils, the aim was to bring different areas of exper- tise together to inspire new opportunities for sci-art collaboration, and to expand the hori- zons of soil protection and communication. The scientific poster session served as a site of communication that was logistically, conceptually, and visually well situated for the integra- tion of a broad range of artworks with and about soil, while a makeshift cinema served to deepen aesthetic and emotional experience in an immersive, atypical conference gathering space. Images and descriptions of selected projects as well as a complete list of participating artists and scientific session topics is documented on www.soilarts.org. 2 Andrea von Braun Stiftung voneinander wissen 1. Introduction: Integrated Art and Film Program at the 20th World Congress of Soil Science From June 8 to June 13, 2014 I co-curated a poster exhibition of artists’ works and a film pro- gram at the 20th World Congress of Soil Science, (20WCSS) in Jeju, Korea with Prof. Dr. Gerd Wessolek, chair of the Department for Soil Protection, Institute for Ecology ate th Technische Universität Berlin. -

ANNALES ANGLAIS Terminales Séries C Et D

BURKINA FASO --------- Unité – Progrès – Justice MINISTERE DE L’EDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L’ALPHABETISATION ET DE LA PROMOTION DES LANGUES NATIONALES ANNALES ANGLAIS Terminales séries C et D 1 Auteurs : Christian Paulin ZOURE, IES Salam ZOROM, IES Tendouindé Bruno NIKIEMA , IES Maquette et mise en page : Salifou OUEDRAOGO ISBN : Tous droits réservés : © Ministre de l’Education nationale, de l’Alphabétisation Et de la Promotion des Langues nationales Edition : Direction générale de la Recherche en Education et de l’Innovation pédagogique 2 PREFACE 3 4 RAPPEL DE COURS 5 Généralités Ces annales ont été rédigées par une équipe d’encadreurs pédagogiques d’anglais du Burkina Faso. • Objectifs du document Ce document vise à : contribuer à assurer la continuité des apprentissages en dehors de la classe ; mettre à la disposition des élèves des sujets de préparation à l’examen du baccalauréat séries C et D ; donner des orientations pour réussir l’épreuve écrite du baccalauréat séries C et D. • Structure du document Ce document est constitué de deux parties. La première partie comporte onze (11) sujets proposés aux examens du baccalauréat séries C et D des années antérieures et la seconde les propositions de corrigés. • Description de l’épreuve d’anglais au baccalauréat séries C et D L’épreuve d’anglais au baccalauréat séries C et D dure deux (2) heures. Elle comporte deux parties essentielles : un texte ; un guided commentary constitué: − d’une série de quatre (4) questions de compréhension du texte et − d’une question de rédaction personnelle sur un thème donné ayant un lien avec la thématique développée dans le texte.