1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007

Copyright by Gary Dean Beckman 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Gary Dean Beckman Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism Committee: ____________________________________ Andrew Dell’ Antonio, Supervisor ____________________________________ Susan Jackson ____________________________________ Rebecca Baltzer ____________________________________ Elliot Antokoletz ____________________________________ Susan R. Boettcher The Sacred Lute: Intabulated Chorales from Luther’s Age to the beginnings of Pietism by Gary Dean Beckman, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge Dr. Douglas Dempster, interim Dean, College of Fine Arts, Dr. David Hunter, Fine Arts Music Librarian and Dr. Richard Cherwitz, Professor, Department of Communication Studies Coordinator from The University of Texas at Austin for their help in completing this work. Emeritus Professor, Dr. Keith Polk from the University of New Hampshire, who mentored me during my master’s studies, deserves a special acknowledgement for his belief in my capabilities. Olav Chris Henriksen receives my deepest gratitude for his kindness and generosity during my Boston lute studies; his quite enthusiasm for the lute and its repertoire ignited my interest in German lute music. My sincere and deepest thanks are extended to the members of my dissertation committee. Drs. Rebecca Baltzer, Susan Boettcher and Elliot Antokoletz offered critical assistance with this effort. All three have shaped the way I view music. -

Aj. Orlando Di Lasso's Missa Ad Imitationem Moduli Doulce

379 A/8/J /AJ. ORLANDO DI LASSO'S MISSA AD IMITATIONEM MODULI DOULCE MEMOIRE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE MASS AND ITS MODEL DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By Jan Hanson Denton, Texas August, 1986 d • i Hanson, Jan L., Orlando di Lasso's Missa Doulce Memoire: An Examination of the Mass and Its Model, Doctor of Musical Arts (Conducting), August, 19b6, pp. 33, 3 figures, 10 examples, bibliography, 37 titles. Orlando di Lasso is regarded as one of the great polyphonic masters of the Renaissance. An international composer of both sacred and secular music, his sacred works have always held an important place in the choral repertory. Especially significant are Lasso's Parody Masses, which comprise the majority of settings in this genre. The Missa Ad Imitatiomem Moduli Doulce Memoire and its model, the chanson Doulce Memoire by Sandrin, have been selected as the subject of this lecture recital. In the course of this study, the two works have been compared and analyzed, focusing on the exact material which has been borrowed from the chanson. In addition to the borrowed material, the longer movements, especially the Gloria and the Credo, exhibit considerable free material. This will be considered in light of its relation to the parody sections. Chapter One gives an introduction to the subject of musical parody with definitions of parody by several contemporary authors. In addition, several writers of the sixteenth century, including Vicentino, Zarlino, Ponzio, and Cerone are mentioned. -

Hieronymus Praetorius

Hieronymus Praetorius Maundy Thursday Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum 1 Orlande de Lassus (1532–1594) Tristis est anima mea [4:10] 2 Jacob Handl (Gallus) (1550–1591) Filiae Jerusalem, nolite [4:48] SIGLO DE ORO | PATRICK ALLIES Good Friday 3 Hieronymus Praetorius (1560–1629) O vos omnes [4:05] 4 Hans Leo Hassler (1564–1612) Deus, Deus meus [3:44] Easter Day 5 Hieronymus Praetorius Tulerunt Dominum meum [6:47] 6 Hieronymus Praetorius Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum – Kyrie [3:02] 7 Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum – Gloria [5:35] Delphian Records and Siglo de Oro are grateful to the Friends and Patrons of Siglo de Oro, Steve Brosnan, Jill Franklin and Bob Allies, Fred and Barbara Gable, Sonia Jacobson, Alan Leibowitz, Séamus McGrenera, Felix and 8 Andrea Gabrieli (c.1533–1585) Maria stabat ad monumentum [5:22] Lizzie Meston, Benedict and Anne Singer and Melissa Scott; to Morgan Rousseaux for sponsoring track 5; and to the Gemma Classical Music Trust for their generous contribution towards the production of this recording. Gemma Classical Music Trust is a Registered Charity No 1121090. 9 Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum – Credo [9:39] 10 Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum – Sanctus & Benedictus [4:04] Siglo de Oro are grateful also to Dr Frederick K. Gable for his help and supervision in the preparation for this disc. The Praetorius motets and mass were edited from the original prints by Frederick K. Gable and the Missa Tulerunt Dominum 11 Missa Tulerunt Dominum meum – Agnus Dei [4:35] meum is published by the American Institute of Musicology in Corpus Mensurabilis Musicae, vol. -

English Lute Manuscripts and Scribes 1530-1630

ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 An examination of the place of the lute in 16th- and 17th-century English Society through a study of the English Lute Manuscripts of the so-called 'Golden Age', including a comprehensive catalogue of the sources. JULIA CRAIG-MCFEELY Oxford, 2000 A major part of this book was originally submitted to the University of Oxford in 1993 as a Doctoral thesis ENGLISH LUTE MANUSCRIPTS AND SCRIBES 1530-1630 All text reproduced under this title is © 2000 JULIA CRAIG-McFEELY The following chapters are available as downloadable pdf files. Click in the link boxes to access the files. README......................................................................................................................i EDITORIAL POLICY.......................................................................................................iii ABBREVIATIONS: ........................................................................................................iv General...................................................................................iv Library sigla.............................................................................v Manuscripts ............................................................................vi Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed sources............................ix GLOSSARY OF TERMS: ................................................................................................XII Palaeographical: letters..............................................................xii -

MUSIC in the RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: a Norton History Walter Frisch Series Editor

MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Western Music in Context: A Norton History Walter Frisch series editor Music in the Medieval West, by Margot Fassler Music in the Renaissance, by Richard Freedman Music in the Baroque, by Wendy Heller Music in the Eighteenth Century, by John Rice Music in the Nineteenth Century, by Walter Frisch Music in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries, by Joseph Auner MUSIC IN THE RENAISSANCE Richard Freedman Haverford College n W. W. NORTON AND COMPANY Ƌ ƋĐƋ W. W. Norton & Company has been independent since its founding in 1923, when William Warder Norton and Mary D. Herter Norton first published lectures delivered at the People’s Institute, the adult education division of New York City’s Cooper Union. The firm soon expanded its program beyond the Institute, publishing books by celebrated academics from America and abroad. By midcentury, the two major pillars of Norton’s publishing program—trade books and college texts— were firmly established. In the 1950s, the Norton family transferred control of the company to its employees, and today—with a staff of four hundred and a comparable number of trade, college, and professional titles published each year—W. W. Norton & Company stands as the largest and oldest publishing house owned wholly by its employees. Copyright © 2013 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Editor: Maribeth Payne Associate Editor: Justin Hoffman Assistant Editor: Ariella Foss Developmental Editor: Harry Haskell Manuscript Editor: Bonnie Blackburn Project Editor: Jack Borrebach Electronic Media Editor: Steve Hoge Marketing Manager, Music: Amy Parkin Production Manager: Ashley Horna Photo Editor: Stephanie Romeo Permissions Manager: Megan Jackson Text Design: Jillian Burr Composition: CM Preparé Manufacturing: Quad/Graphics-Fairfield, PA A catalogue record is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-393-92916-4 W. -

The French Connection

French Music from the Renaissance and Baroque Le berger et la bergère Jean Mouton (ca. 1459-1522) S’il est a ma poste Nicolle des Celliers d’Hesdin (? – 1538) Demandes-tu, douce ennemie Nicola de la Grotte (1530 – ca. 1600) Chose commune Anon (text by Francis I) Pour ung plaisir Thomas Crequillon. (ca. 1500 - 1557) Si des haulx cieulx Milles regretz Josquin des Pres (ca. 1450 – 1521) La la la, je ne l’ose dire Pierre Certon (ca. 1520 – 1572) Ce moys de mai Clement Janequin (ca. 1485 – 1558) A ce joli mois Revecy venir dü Printans Claude le Jeune (ca. 1528 - 1600) Susanne un jour Didier Lupi the Second. (mid-16th century) Susanne un jour Alfonso Ferrabosco, Sr. (ca. 1578-1628) Five French dances Michael Praetorius (1571 – 1621) Spagnoletta Bourées I and II Volta Branle Fantasie No. 2 Etienne Moulinié (1599 – 1676) Tombeau “Les Regrets” Sieur de St. Colombe (1640-1700) Quator Michel-Richard de Lalande (1657 – 1726) Three movements from the Suite in A minor Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643 – 1704) Gigue angloise Gigue francoise Passacaille March for the Entry of Turks Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632- 1687) Program Notes The music of 16th century France was influenced by the religious/political, social and technological world in which it was created. Our program of 16th and 17th century French song (chansons) and dances is a case in point. The invention ofthe printing press in the late 15th century had a dramatic effect on the accessibility of music. Publishers such as Pierre Attaingnant in Paris, Tielman Susato and Christopher Plantin in Antwerp, Ottaviano Petrucci in Venice, Jacques Moderne in Lyons and Pierre Phalese in Louvain turned out many collections ofchansons, motets, masses, psalms and dances. -

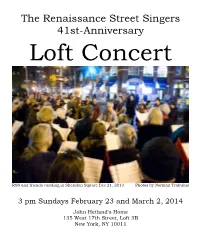

Loft Concert Program

The Renaissance Street Singers 41st-Anniversary Loft Concert RSS and friends caroling in Sheridan Square Dec 21, 2013 Photos by Norman Trabulus 3 pm Sundays February 23 and March 2, 2014 John Hetland's Home 135 West 17th Street, Loft 3B New York, NY 10011 - 2 - Polyphonic Sacred Music In polyphony (meaning “many sounds”), the dominant form of religious music in Europe during the Renaissance, each voice (soprano, alto, etc.) sings an interesting melodic line, with rhythmic complexity, and the voices intertwine to make a complex weaving of sound. The composers, writing for their strong beliefs, put their best efforts into the music. The result is beautiful music that transcends the religious beliefs from which it springs. The Renaissance Street Singers The Renaissance Street Singers, founded in 1973 by John Het- land, perform polyphonic 15th- and 16th-century sacred music a cappella on the sidewalks and in the public spaces of New York. The motivation is a love for this music and the wish to share it with others. Concerts are on Sundays about twice a month, usually from 2 to 4 p.m., always free. Loft Concert We are pleased to perform here in the Loft once a year for your enjoyment. The music is our usual repertoire, mostly unrelated compositions that we like. This year's concert contains works by eleven composers, four of whom are from the vicinity of the Netherlands, three from England, two from France and one each from Germany and Italy. We are doing only one Mass section this time, the Credo from John Sheppard’s glorious Missa “Cantate.” For more information and a performance schedule, visit: www.StreetSingers.org - 3 - Today's Concert Gaudent in caelis Jean Maillard (French; c.1510-c.1570) Salve Regina Orlande de Lassus (Franco-Flemish; c.1532-1594) O altitudo divitiarum Giaches de Wert (Flemish; 1535-1596) Stabat mater dolorosa John Browne (English; late 15th cen.) Ego flos campi Jacobus Clemens non Papa (S. -

Chansons Polyphoniques Françaises

1/23 Data Chansons polyphoniques françaises Thème : Chansons polyphoniques françaises Origine : RAMEAU Domaines : Musique Autre forme du thème : Polyphonies françaises Notices thématiques en relation (2 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Termes reliés (2) Airs de cour Chansons françaises Documents sur ce thème (28 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Livres (26) La chanson de Debussy à , Aix-en-Provence : Bookelis La chanson polyphonique , Marielle Cafafa, Paris : Ravel , 2018 française au temps de l'Harmattan , impr. 2017 (2018) Debussy, Ravel et Poulenc (2017) Songs, scribes, and society , Jane Elise Alden, New Allegorical play in the Old , Sylvia Jean Huot, Stanford (2010) York (N.Y.) : Oxford French motet (Calif.) : Stanford University University Press , 2010 (1997) press , 1997 De Guillaume Dufay à , Ignace Bossuyt, Paris : Hexachord, Mensur und , Christian Berger, Stuttgart Roland de Lassus Cerf ; Bruxelles : Racine , Textstruktur : F. Steiner , 1992 (1996) 1996 (1992) Die Chansons Johannes , Clemens Goldberg, Laaber The Partbooks of a , George Karl Diehl, Ann Ockeghems : Laaber-Verlag , 1992 Renaissance merchant Arbor ; London : University (1992) (1978) microfilms international , 1978 data.bnf.fr 2/23 Data The chanson in the humanist era. - [5] A Chanson rustique of the early Renaissance : Bon (1976) temps. - [21] (1967) Aspects littéraires de la , Georges Dottin, Lille : La Chanson française au XVIe siècle. - [33] chanson musicale à Faculté des lettres et (1960) l'époque de Marot sciences humaines , 1964 (1964) Le "Livre des vers du luth", , André Verchaly A Chanson sequence, by Fevin. - [18] manuscrit d'Aix-en- (1903-1976), Aix-en- (1957) Provence. Préface de Paul Provence : la Pensée Juif universitaire , [1958] (1958) Notes sur quelques chansons normandes du manuscrit Vaudeville, vers mesurés et , Kenneth Jay Levy, [S.l.] : de Bayeux. -

The Madrigal History of Jacques Arcadelt (Ca. 1505-1568)

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 Classicization in the renaissance: the madrigal history of Jacques Arcadelt (ca. 1505-1568) Harris, Kenneth Paul Harris, K. P. (1999). Classicization in the renaissance: the madrigal history of Jacques Arcadelt (ca. 1505-1568) (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/21509 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25051 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca TJMVERSITY OF CALGARY Classicization in the Renaissance: The Madrigal History of Jacques kcadelt (ca. 1505-1568) K. Paul Harris A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Ih PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 1999 0 K. Paul Harris, 1999 National Library Bibliotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON K1AON4 OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada Yaur fib Votre reference Our fib Nutre reterence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant ii la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prster, distribuer ou copies of hsthesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

From Heaven on High" by Michael Caruso, December 2008

Review of "From Heaven on High" by Michael Caruso, December 2008 Chestnut Hill continues to be the center of the region's musical celebration of the Christmas season. Alan Harler conducted the Mendelssohn Club in two performances of its annual Christmas concert last Saturday afternoon and evening, December 13, in St. Paul's Episcopal Church. This past Friday night, Piffaro kicked off its series of four renditions of its Christmas program with the first one presented in the Presbyterian Church of Chestnut Hill. And Valentin Radu led the Camerata Ama Deus in its Christmas program in St. Paul's Church. This year's installment of the Mendelssohn Club's holiday concert was entitled "From Heaven on High." Centering on the German text, "Vom Himmel hoch," used by Bach, Mendelssohn and W.W. Gilchrist (the Mendelssohn Club's founder), and surrounded by complimentary lyrics and music, the concert cemented Alan Harler's reputation as the region's foremost builder of memorable programs. Not only did Harler, his singers, the Mendelssohn Brass and organist Michael Stairs offer a little bit of just about everything in the holiday mode, they did so with such perfect balance and cohesion that I found myself wondering why other music directors can't do the same. The mix of old, recent and new -- with audience participation cleverly interspersed throughout -- couldn't have been improved upon -- except by Harler, himself, next year. The program opened with Felix Mendelssohn's six-movement motet, "Vom Himmel hoch" (From Heaven above to earth I come). Harler and the choir caught the vibrance of the opening chorus with singing that I can only describe as old-fashioned in its fullness of tone and, therefore, exceptionaly expressive in its projection of heart, spirit and soul. -

Orlando Di Lasso Studies

Orlando di Lasso Studies Orlando di Lasso was the most famous and most popular composer of the second half of the 1500s. This book of essays written by leading scholars from Europe and the United States is the first full-length survey in English of a broad spectrum of Lasso’s music. The essays discuss his large and varied output with regard to structure, expressive qualities, liturgical aspects, and its use as a model by other composers, focusing in turn on his Magnificat settings, masses, motets, hymns and madrigals. His relationship to contemporaries and younger composers is the main subject of three essays and is touched on throughout the book, together with the circulation of his music in print and in manuscript. His attitude toward modal theory is explored in one essay, another considers the relationship of verbal and musical stress in Lasso’s music and what this implies both for scholars and for performers. Peter Bergquist is Professor Emeritus of Music at the University of Oregon. He has edited works by Orlando di Lasso for Bärenreiter Verlag and A-R Editions. Orlando di Lasso at the age of thirty-nine, from Moduli quinis vocibus (Paris: Adrian Le Roy and Robert Ballard, RISM 1571a), quinta vox partbook, reproduced by courtesy of the Musikabteilung, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich. Orlando di Lasso Studies edited by peter bergquist CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521593878 © Cambridge University Press 1999 This publication is in copyright. -

Music About Music & Musicians

Music About Music & Musicians RenChorNY Claude Lévy, Artistic Director and Conductor Lassus: Musica Dei Donum optimi Moulu: Mater floreat florescat Compère: Omnium bonorum plena Schuyt: O Leyda gratiosa Senfl:Das Glaut zu Speyer Josquin: Déploration re; Ockeghem Mouton: re:Févin Certon re: Sermisy Lassus: L’Echo Stobäus: Laudent Deum Lassus: In hora ultima Two Concerts OCTOBER 14 & OCTOBER 18, 2017 The “Music about Music and Musicians” Concert Today’s concert offers music from the 16th century Low Countries, featuring compo- sitions which honor music itself or musicians. Apart from the purely liturgical, the music of that milieu expressed the inner reflections of medieval and baroque musicians; in this respect, it reflects the other art forms of that culture. Specifically, structural concepts of polyphonic music (e.g., balance, flow, and contrast) were profoundly influ- enced by the work of Flemish masters and their architecture. Historically, elements of earlier music were retained and transformed in this evolving music. Plainchant was used as cantus firmus. The familiar medieval English thirds (which had crossed the channel with Dunstable and others) found a new home with Du Fay, et al. Their texts acknowledged direct inspiration by the Psalmists, Orphic myths, and classical founders of the art like Pythagoras. More specifically, these pieces from the Franco- Flemish School show how changes in that region encouraged communication and exchange of influences among artists across Europe. Near ports and along transporta- tion routes, as the isolation imposed by feudal political and financial systems began to ease up, the mercantile society of guilds and apprenticeships enabled artists to study and teach in distant regions.