Turing Machines Read K & S 4.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS 154 NOTES Part 1. Finite Automata

CS 154 NOTES ARUN DEBRAY MARCH 13, 2014 These notes were taken in Stanford’s CS 154 class in Winter 2014, taught by Ryan Williams. I live-TEXed them using vim, and as such there may be typos; please send questions, comments, complaints, and corrections to [email protected]. Thanks to Rebecca Wang for catching a few errors. CONTENTS Part 1. Finite Automata: Very Simple Models 1 1. Deterministic Finite Automata: 1/7/141 2. Nondeterminism, Finite Automata, and Regular Expressions: 1/9/144 3. Finite Automata vs. Regular Expressions, Non-Regular Languages: 1/14/147 4. Minimizing DFAs: 1/16/14 9 5. The Myhill-Nerode Theorem and Streaming Algorithms: 1/21/14 11 6. Streaming Algorithms: 1/23/14 13 Part 2. Computability Theory: Very Powerful Models 15 7. Turing Machines: 1/28/14 15 8. Recognizability, Decidability, and Reductions: 1/30/14 18 9. Reductions, Undecidability, and the Post Correspondence Problem: 2/4/14 21 10. Oracles, Rice’s Theorem, the Recursion Theorem, and the Fixed-Point Theorem: 2/6/14 23 11. Self-Reference and the Foundations of Mathematics: 2/11/14 26 12. A Universal Theory of Data Compression: Kolmogorov Complexity: 2/18/14 28 Part 3. Complexity Theory: The Modern Models 31 13. Time Complexity: 2/20/14 31 14. More on P versus NP and the Cook-Levin Theorem: 2/25/14 33 15. NP-Complete Problems: 2/27/14 36 16. NP-Complete Problems, Part II: 3/4/14 38 17. Polytime and Oracles, Space Complexity: 3/6/14 41 18. -

Computability and Incompleteness Fact Sheets

Computability and Incompleteness Fact Sheets Computability Definition. A Turing machine is given by: A finite set of symbols, s1; : : : ; sm (including a \blank" symbol) • A finite set of states, q1; : : : ; qn (including a special \start" state) • A finite set of instructions, each of the form • If in state qi scanning symbol sj, perform act A and go to state qk where A is either \move right," \move left," or \write symbol sl." The notion of a \computation" of a Turing machine can be described in terms of the data above. From now on, when I write \let f be a function from strings to strings," I mean that there is a finite set of symbols Σ such that f is a function from strings of symbols in Σ to strings of symbols in Σ. I will also adopt the analogous convention for sets. Definition. Let f be a function from strings to strings. Then f is computable (or recursive) if there is a Turing machine M that works as follows: when M is started with its input head at the beginning of the string x (on an otherwise blank tape), it eventually halts with its head at the beginning of the string f(x). Definition. Let S be a set of strings. Then S is computable (or decidable, or recursive) if there is a Turing machine M that works as follows: when M is started with its input head at the beginning of the string x, then if x is in S, then M eventually halts, with its head on a special \yes" • symbol; and if x is not in S, then M eventually halts, with its head on a special • \no" symbol. -

COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Insights on Computability Turing Machines Are a Model of Computation Two (No Longer) Surpris

Insights on Computability Turing machines are a model of computation COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Lecture 11: Turing Machines Two (no longer) surprising facts: Marius Minea Although simple, can describe everything [email protected] a (real) computer can do. University of Massachusetts Amherst Although computers are powerful, not everything is computable! Plus: “play” / program with Turing machines! 13 February 2019 Why should we formally define computation? Must indeed an algorithm exist? Back to 1900: David Hilbert’s 23 open problems Increasingly a realization that sometimes this may not be the case. Tenth problem: “Occasionally it happens that we seek the solution under insufficient Given a Diophantine equation with any number of un- hypotheses or in an incorrect sense, and for this reason do not succeed. known quantities and with rational integral numerical The problem then arises: to show the impossibility of the solution under coefficients: To devise a process according to which the given hypotheses or in the sense contemplated.” it can be determined in a finite number of operations Hilbert, 1900 whether the equation is solvable in rational integers. This asks, in effect, for an algorithm. Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem (1928): Is there an algorithm that And “to devise” suggests there should be one. decides whether a statement in first-order logic is valid? Church and Turing A Turing machine, informally Church and Turing both showed in 1936 that a solution to the Entscheidungsproblem is impossible for the theory of arithmetic. control To make and prove such a statement, one needs to define computability. In a recent paper Alonzo Church has introduced an idea of “effective calculability”, read/write head which is equivalent to my “computability”, but is very differently defined. -

Computability Theory

CSC 438F/2404F Notes (S. Cook and T. Pitassi) Fall, 2019 Computability Theory This section is partly inspired by the material in \A Course in Mathematical Logic" by Bell and Machover, Chap 6, sections 1-10. Other references: \Introduction to the theory of computation" by Michael Sipser, and \Com- putability, Complexity, and Languages" by M. Davis and E. Weyuker. Our first goal is to give a formal definition for what it means for a function on N to be com- putable by an algorithm. Historically the first convincing such definition was given by Alan Turing in 1936, in his paper which introduced what we now call Turing machines. Slightly before Turing, Alonzo Church gave a definition based on his lambda calculus. About the same time G¨odel,Herbrand, and Kleene developed definitions based on recursion schemes. Fortunately all of these definitions are equivalent, and each of many other definitions pro- posed later are also equivalent to Turing's definition. This has lead to the general belief that these definitions have got it right, and this assertion is roughly what we now call \Church's Thesis". A natural definition of computable function f on N allows for the possibility that f(x) may not be defined for all x 2 N, because algorithms do not always halt. Thus we will use the symbol 1 to mean “undefined". Definition: A partial function is a function n f :(N [ f1g) ! N [ f1g; n ≥ 0 such that f(c1; :::; cn) = 1 if some ci = 1. In the context of computability theory, whenever we refer to a function on N, we mean a partial function in the above sense. -

Models of Computation

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 6.004 Computation Structures Spring 2009 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. Models of computation Problem 1. In lecture, we saw an enumeration of FSMs having the property that every FSM that can be built is equivalent to some FSM in that enumeration. A. We didn't deal with FSMs having different numbers of inputs and outputs. Where will we find a 5-input, 3-output FSM in our enumeration? We find a 5-input, 5-output FSM and don't use the extra outputs. B. Can we also enumerate finite combinational logic functions? If so, describe such an enumeration; if not, explain your reasoning. Yes. One approach is to enumerate ROMs, in much the same way as we did for the logic in our FSMs. For single-output functions, we can enumerate 1-input truth tables, 2-input truth tables, etc. This can clearly be extended to multiple outputs, as was done in lecture. An alternative approach is to enumerate (say) all possible acyclic circuits using 2-input NAND gates. C. Why do 6-3s think they own this enumeration trick? Can we come up with a scheme for enumerating functions of continuous variables, e.g. an enumeration that will include things like sin(x), op amps, etc? No. The thing that makes enumeration work is the finite number of combination functions there are for each number of inputs. There are only 16 2-input combinational functions; but there are infinitely many continuous 2-input functions. -

Turing Machines and Separation Logic (Work in Progress)

Turing Machines and Separation Logic (Work in Progress) Jian Xu Xingyuan Zhang PLA University of Science and Technology Christian Urban King's College London Imperial College, 24 November 2013 -- p. 1/26 Why Turing Machines? we wanted to formalise computability theory at the beginning, it was just a student project Computability and Logic (5th. ed) Boolos, Burgess and Jeffrey found an inconsistency in the definition of halting computations (Chap. 3 vs Chap. 8) Imperial College, 24 November 2013 -- p. 2/26 Why Turing Machines? we wanted to formalise computability theory atTMs the beginning, are a fantastic it was model just a of student low-level project code completely unstructured Spaghetti Code good testbed for verification techniques . Can we verify a program with 38 Mio instructions? we can delayComputability implementing and Logic a (5th.concrete ed) machine model (for OS/low-levelBoolos, Burgess code and Jeffrey verification) found an inconsistency in the definition of halting computations (Chap. 3 vs Chap. 8) Imperial College, 24 November 2013 -- p. 2/26 Why Turing Machines? we wanted to formalise computability theory atTMs the beginning, are a fantastic it was model just a of student low-level project code completely unstructured Spaghetti Code good testbed for verification techniques . Can we verify a program with 38 Mio instructions? we can delayComputability implementing and Logic a (5th.concrete ed) machine model (for OS/low-levelBoolos, Burgess code and Jeffrey verification) found an inconsistency in the definition of halting computations -

![Alan Turing and the Unsolvable Problem [8Pt] to Halt Or Not to Halt](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9155/alan-turing-and-the-unsolvable-problem-8pt-to-halt-or-not-to-halt-1379155.webp)

Alan Turing and the Unsolvable Problem [8Pt] to Halt Or Not to Halt

Alan Turing and the Unsolvable Problem To Halt or Not to Halt|That Is the Question Cristian S. Calude 26 April 2012 Alan Turing Alan Mathison Turing was born in a nursing home in Paddington, London, now the Colonnade Town House on 23 June 1912, less than three months after the sinking of the Titanic. He was to become, like Freud, who stayed briefly in the House in 1938, an explorer of the mind. But his life would not make him as famous as Freud, at least for a while. Sherborne School Turing started at Sherborne School, a classic English \public school" in the town of Sherborne, Dorset, in south-west England. Sherborne was a boys boarding school and isolation from family had a life-long affect. With very bad reports he was nearly stopped from taking the School Certificate. Reports English: I can forgive his writing, though it is the worst I have ever seen, and I try to view tolerantly his unswerving inexactitude and slipshod, dirty, work, inconsistent though such inexactitude is in a utilitarian; but I cannot forgive the stupidity of his attitude towards sane discussion on the New Testament. Bottom of the class. Maths and science: His work is dirty. Maths and science In spite of the difficult start, in 1928 he was admitted to enter the sixth form of Sherborne School to study mathematics and science. He read mathematics as an undergraduate stu- dent at King's College, Cambridge, 1931{1934. He read J. von Neumann (quantum physics) and B. Russell (logic). He was elected fellow of King's College, 1935. -

Fsms and Turing Machines

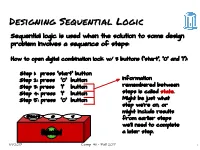

Designing Sequential Logic Sequential logic is used when the solution to some design problem involves a sequence of steps: How to open digital combination lock w/ 3 buttons (“start”, “0” and “1”): Step 1: press “start” button Step 2: press “0” button Information Step 3: press “1” button remembered between Step 4: press “1” button steps is called state. Step 5: press “0” button Might be just what step we’re on, or might include results from earlier steps we’ll need to complete a later step. 11/1/2017 Comp 411 - Fall 2017 1 Implementing a “State Machine” Current State “start” “1” “0” Next State unlock --- 1 --- --- start 0 000 This flavor of “truth-table” is start 000 0 0 1 digit1 0 001 called a start 000 0 1 0 error 0 101 “state-transition start 000 0 0 0 start 0 000 table” digit1 001 0 1 0 digit2 0 010 digit1 001 0 0 1 error 0 101 digit1 001 0 0 0 digit1 0 001 digit2 010 0 1 0 digit3 0 011 This is starting to look like a … PROGRAM digit3 011 0 0 1 unlock 0 100 … unlock 100 0 1 0 error 1 101 unlock 100 0 0 1 error 1 101 unlock 100 0 0 0 unlock 1 100 error 101 0 --- --- error 0 101 6 different states → encode using 3 bits 11/1/2017 Comp 411 - Fall 2017 2 Now, We Do It With Hardware! 6 inputs →26 locations each location supplies 4 bits “start” button “0” button unlock “1” button ROM 64x4 Current state Next state 3 3 Q D Trigger update periodically (“clock”) 11/1/2017 Comp 411 - Fall 2017 3 Abstraction du jour: A Finite State Machine m n Clocked FSM A Finite State Machine has: ● k States S1, S2, … Sk (one is the “initial” state) ● m inputs I1, I2, … Im ● n outputs O1, O2, … On ● Transition Rules, S’(Si,I1, I2, … Im) for each state and input combination ● Output Rules, O(Si) for each state 11/1/2017 Comp 411 - Fall 2017 4 Discrete State, Discrete Time While a ROM is shown here in the feedback path any form of combinational logic inputs outputs can be used to construct a state machine. -

Turing Machines 1

CS1010: Theory of Computation Lecture 8: Turning Machines Lorenzo De Stefani Fall 2020 Outline • What are Turing Machines • Turing Machine Scheme • Formal Definition • Languages of a TM • Decidability From Sipser Chapter 3.1 Theory of Computation - Fall'20 10/8/20 1 Lorenzo De Stefani FA, PDA and Turing Machines • Finite Automata: – Models for devices with finite memory • Pushdown Automata: – Models for devices with unlimited memory (stack) that is accessible only in Last-In-First-Out order • Turing Machines (Turing 1936) – Uses unlimited memory as an infinite tape which can be read/written and moved to left or right – Only model thus far that can model general purpose computers – Church-Turing thesis – Still, TM cannot solve all problems Theory of Computation - Fall'20 10/8/20 2 Lorenzo De Stefani Turing Machine Scheme Control Head Tape – a b a b – – – … Turing machines include an infinite tape – Tape uses its own alphabet Γ, with ⌃<latexit sha1_base64="(null)">(null)</latexit> Γ – Initially contains the input string and blanks⇢ everywhere else – Machine can read and write from tape and move left and right after each action – Much more powerful than FIFO stack of PDAs Theory of Computation - Fall'20 10/8/20 3 Lorenzo De Stefani Turing Machine Scheme Control a b a b – – – … The control operates as a state machine – Starts in an initial state – Proceeds in a series of transitions triggered by the symbols on the tape (one at a time) – The machine continues until it enters an accept or reject state at which point it immediately halts and -

Turing Machines: an Introduction

CIT 596 – Theory of Computation 1 Turing Machines: An Introduction We have seen several abstract models of computing devices: Deterministic Finite Automata, Nondeterministic Finite Automata, Non- deterministic Finite Automata with ²-Transitions, Pushdown Automata, and Deterministic Pushdown Automata. However, none of the above “seem to be” as powerful as a real com- puter, right? We now turn our attention to a much more powerful abstract model of a computing device: a Turing machine. This model is believed to do everything that a real computer can do. °c Marcelo Siqueira — Spring 2005 CIT 596 – Theory of Computation 2 Turing Machines: An Introduction A Turing machine is somewhat similar to a finite automaton, but there are important differences: 1. A Turing machine can both write on the tape and read from it. 2. The read-write head can move both to the left and to the right. 3. The tape is infinite. 4. The special states for rejecting and accepting take immediate effect. °c Marcelo Siqueira — Spring 2005 CIT 596 – Theory of Computation 3 Turing Machines: An Introduction Formally, a Turing machine is a 7-tuple, (Q, Σ, Γ, δ, q0, qaccept, qreject), where Q is the (finite) set of states, Σ is the input alphabet such that Σ does not contain the special blank symbol t, Γ is the tape alphabet such that t∈ Γ and Σ ⊆ Γ, δ : Q × Γ → Q × Γ ×{L, R} is the transition function, q0 ∈ Q is the start state, qaccept ∈ Q is the accept state, and qreject ∈ Q is the reject state, where qaccept 6= qreject. -

Finite Automata

Finite Automata CS 2800: Discrete Structures, Spring 2015 Sid Chaudhuri A simplified model String Machine String A simplified model String Machine String Finite sequence of letters from an alphabet Σ, e.g. {0, 1} A general-purpose computer String #uring String Machine A general-purpose computer We might revisit these later String #uring String Machine A general-purpose computer String #uring String Machine Church$#uring #hesis: An% “effecti(e/mechanical/real-*orld” calculation can be carried out on a #uring machine Alan #uring, 1-12 – 1-5/ A simple &computer” Deterministic Finite String 2es/3o Automaton 0DFA1 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 05inary input) An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6nput: 01001 7utput: 2es8 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 6n general, on what binary strings does this DFA return 2es9 An example 1 0 2es 3o 0 1 Ans: All strings with an e(en number of 1's Deterministic Finite Automaton ● A DFA is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, δ, q0, F) Deterministic Finite Automaton ● A DFA is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, δ, q0, F) – Q is a finite set ofstates 2es 3o Deterministic Finite Automaton ● A DFA is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, δ, q0, F) – Q is a finite set ofstates – Σ is a finite input alphabet (e.g. -

Turing Machines Part Two

Turing Machines Part Two Recap from Last Time Our First Turing Machine qacc ☐ → ☐, R a → ☐, R start q0 q1 a → ☐, R ☐ → ☐, R ThisThis is is the the Turing Turing machine’s machine’s finite state control. It issues finite state control. It issues qrej commandscommands that that drive drive the the operationoperation of of the the machine. machine. Our First Turing Machine qacc ☐ → ☐, R a → ☐, R start q0 q1 a → ☐, R ☐ → ☐, R ThisThis is is the the TM’s TM’s infinite infinite tape tape. Each tape cell holds a tape Each tape cell holds a tape qrej symbolsymbol. .Initially, Initially, all all (infinitely (infinitely many)many) tape tape symbols symbols are are blank. blank. … … Our First Turing Machine qacc ☐ → ☐, R a → ☐, R start q0 q1 a → ☐, R TheThe machine machine is is started started with with the the ☐ → ☐, R inputinput string string written written somewhere somewhere onon the the tape. tape. The The tape tape head head initially points to the first symbol initially points to the first symbol qrej ofof the the input input string. string. … a a a a … Our First Turing Machine qacc ☐ → ☐, R a → ☐, R start q0 q1 a → ☐, R ☐ → ☐, R LikeLike DFAs DFAs and and NFAs,NFAs, TMs TMs begin begin executionexecution in in their their q startstart state state. rej … a a a a … Our First Turing Machine qacc ☐ → ☐, R a → ☐, R start q0 q1 a → ☐, R ☐ → ☐, R AtAt each each step, step, the the TMTM only only looks looks at at thethe symbol symbol q immediatelyimmediately under under rej thethe tape tape head head.