TOPIC 4. COVALENT COMPOUNDS: Bonding, Naming, Polyatomic Ions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transport of Dangerous Goods

ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Recommendations on the TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS Model Regulations Volume I Sixteenth revised edition UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2009 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ST/SG/AC.10/1/Rev.16 (Vol.I) Copyright © United Nations, 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may, for sales purposes, be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the United Nations. UNITED NATIONS Sales No. E.09.VIII.2 ISBN 978-92-1-139136-7 (complete set of two volumes) ISSN 1014-5753 Volumes I and II not to be sold separately FOREWORD The Recommendations on the Transport of Dangerous Goods are addressed to governments and to the international organizations concerned with safety in the transport of dangerous goods. The first version, prepared by the United Nations Economic and Social Council's Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods, was published in 1956 (ST/ECA/43-E/CN.2/170). In response to developments in technology and the changing needs of users, they have been regularly amended and updated at succeeding sessions of the Committee of Experts pursuant to Resolution 645 G (XXIII) of 26 April 1957 of the Economic and Social Council and subsequent resolutions. -

Determination of Aluminium As Oxide

DETERMINATION OF ALUMINIUM AS OXIDE By William Blum CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 515 II. General principles 516 III. Historical 516 IV. Precipitation of aluminium hydroxide. 518 1. Hydrogen electrode studies 518 (a) The method 518 (b) Apparatus and solutions employed 518 (c) Results of hydrogen electrode experiments 519 (d) Conclusions from hydrogen electrode experiments 520 2. Selection of an indicator for denning the conditions of precipita- '. tion . 522 3. Factors affecting the form of the precipitate 524 4. Precipitation in the presence of iron 525 V. Washing the precipitate . 525 VI. Separation from other elements 526 VII. Ignition and weighing of the precipitate 528 1. Hygroscopicity of aluminium oxide 529 2. Temperature and time of ignition 529 3. Effect of ammonium chloride upon the ignition 531 VIII. Procedure recommended 532 IX. Confirmatory experiments 532 X. Conclusions '534 I. INTRODUCTION Although a considerable number of precipitants have been pro- posed for the determination of aluminium, direct precipitation of aluminium hydroxide by means of ammonium hydroxide, fol- lowed by ignition to oxide, is most commonly used, especially if no separation from iron is desired, in which latter case special methods must be employed. While the general principles involved in this determination are extremely simple, it has long been recog- nized that certain precautions in the precipitation, washing, and ignition are necessary if accurate results are to be obtained. While, however, most of these details have been studied and dis- cussed by numerous authors, it is noteworthy that few publica- tions or textbooks have taken account of all the factors. In the 515 ; 516 Bulletin of the Bureau of Standards [Voi.i3 present paper it seems desirable, therefore, to assemble the various recommendations and to consider their basis and their accuracy. -

Multivalent Metals and Polyatomic Ions 1

Name Date Comprehension Section 4.2 Use with textbook pages 189–193. Multivalent metals and polyatomic ions 1. Define the following terms: (a) ionic compound (b) multivalent metal (c) polyatomic ion 2. Write the formulae and names of the compounds with the following combination of ions. The first row is completed to help guide you. Positive ion Negative ion Formula Compound name (a) Pb2+ O2– PbO lead(II) oxide (b) Sb4+ S2– (c) TlCl (d) tin(II) fluoride (e) Mo2S3 (f) Rh4+ Br– (g) copper(I) telluride (h) NbI5 (i) Pd2+ Cl– 3. Write the chemical formula for each of the following compounds. (a) manganese(II) chloride (f) vanadium(V) oxide (b) chromium(III) sulphide (g) rhenium(VII) arsenide (c) titanium(IV) oxide (h) platinum(IV) nitride (d) uranium(VI) fluoride (i) nickel(II) cyanide (e) nickel(II) sulphide (j) bismuth(V) phosphide 68 MHR • Section 4.2 Names and Formulas of Compounds © 2008 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited 0056_080_BCSci10_U2CH04_098461.in6856_080_BCSci10_U2CH04_098461.in68 6688 PDF Pass 77/11/08/11/08 55:25:38:25:38 PPMM Name Date Comprehension Section 4.2 4. Write the formulae for the compounds formed from the following ions. Then name the compounds. Ions Formula Compound name + – (a) K NO3 KNO3 potassium nitrate 2+ 2– (b) Ca CO3 + – (c) Li HSO4 2+ 2– (d) Mg SO3 2+ – (e) Sr CH3COO + 2– (f) NH4 Cr2O7 + – (g) Na MnO4 + – (h) Ag ClO3 (i) Cs+ OH– 2+ 2– (j) Ba CrO4 5. Write the chemical formula for each of the following compounds. (a) barium bisulphate (f) calcium phosphate (b) sodium chlorate (g) aluminum sulphate (c) potassium chromate (h) cadmium carbonate (d) calcium cyanide (i) silver nitrite (e) potassium hydroxide (j) ammonium hydrogen carbonate © 2008 McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited Section 4.2 Names and Formulas of Compounds • MHR 69 0056_080_BCSci10_U2CH04_098461.in6956_080_BCSci10_U2CH04_098461.in69 6699 PDF Pass77/11/08/11/08 55:25:39:25:39 PPMM Name Date Comprehension Section 4.2 Use with textbook pages 186–196. -

Risto Laitinen/August 4, 2016 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Division VIII Chemical Nomenclature and Structur

Approved Minutes, Busan 2015 Risto Laitinen/August 4, 2016 International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry Division VIII Chemical Nomenclature and Structure Representation Approved Minutes of Division Committee Meeting in Busan, Korea, 8–9 August, 2015 1. Welcome, introductory remarks and housekeeping announcements Karl-Heinz Hellwich (KHH) welcomed everybody to the meeting, extending a special welcome to those who were attending the Division Committee meeting for the first time. He described house rules and arrangements during the meeting. KHH also regretfully reported that it has come to his attention that since the Bangor meeting in August 2014, Prof. Derek Horton (Member, Division VIII task groups on Carbohydrate and Flavonoids nomenclature; Associate Member, IUBMB-IUPAC Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature) and Dr. Libuse Goebels, Member of the former Commission on Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry) have passed away. The meeting attendees paid a tribute to their memory by a moment of silence. 2. Attendance and apologies Present: Karl-Heinz Hellwich (president, KHH) , Risto Laitinen (acting secretary, RSL), Richard Hartshorn (past-president, RMH), Michael Beckett (MAB), Alan Hutton (ATH), Gerry P. Moss (GPM), Michelle Rogers (MMR), Jiří Vohlídal (JV), Andrey Yerin (AY) Observers: Leah McEwen (part time, chair of proposed project, LME), Elisabeth Mansfield (task group chair, EM), Johan Scheers (young observer, day 1; JS), Prof. Kazuyuki Tatsumi (past- president of the union, part of day 2) Apologies: Ture Damhus (secretary, TD), Vefa Ahsen, Kirill Degtyarenko, Gernot Eller, Mohammed Abul Hashem, Phil Hodge (PH), Todd Lowary, József Nagy, Ebbe Nordlander (EN), Amélia Pilar Rauter (APR), Hinnerk Rey (HR), John Todd, Lidija Varga-Defterdarović. -

The Effect of Various Hydroxide and Salt Additives on the Reduction of Fluoride Ion Mobility in Industrial Waste

sustainability Article The Effect of Various Hydroxide and Salt Additives on the Reduction of Fluoride Ion Mobility in Industrial Waste Tadas Dambrauskas 1,* , Kestutis Baltakys 1, Agne Grineviciene 1 and Valdas Rudelis 2 1 Department of Silicate Technology, Kaunas University of Technology, LT-50270 Kaunas, Lithuania; [email protected] (K.B.); [email protected] (A.G.) 2 JSC “Lifosa”, LT-57502 Kedainiai, Lithuania; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In this work, the influence of various hydroxide and salt additives on the removal of F− ions from silica gel waste, which is obtained during the production of AlF3, was examined. The leaching of the mentioned ions from silica gel waste to the liquid medium was achieved by the application of different techniques: (1) leaching under static conditions; (2) leaching under dynamic conditions by the use of continuous liquid medium flow; and (3) leaching in cycles under dynamic conditions. It was determined that the efficiency of the fluoride removal from this waste depends on the w/s ratio, the leaching conditions, and the additives used. It was proven that it is possible to reduce the concentration of fluorine ions from 10% to <5% by changing the treatment conditions and by adding alkaline compounds. The silica gel obtained after the leaching is a promising silicon dioxide source. Keywords: fluorine ions; silica gel waste; leaching; hydroxide additives Citation: Dambrauskas, T.; Baltakys, K.; Grineviciene, A.; Rudelis, V. The 1. Introduction Effect of Various Hydroxide and Salt Waste management and the reduction of pollution are the priority areas of environ- Additives on the Reduction of mental protection in the World [1–4]. -

Aluminium Distearate, Aluminium Hydroxide Acetate, Aluminium Phosphate and Aluminium Tristearate

The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products Veterinary Medicines Evaluation Unit EMEA/MRL/393/98-FINAL April 1998 COMMITTEE FOR VETERINARY MEDICINAL PRODUCTS ALUMINIUM DISTEARATE, ALUMINIUM HYDROXIDE ACETATE, ALUMINIUM PHOSPHATE AND ALUMINIUM TRISTEARATE SUMMARY REPORT 1. Aluminium is an ubiquitous element in the environment. It is present in varying concentrations in living organisms and in foods. Aluminium compounds are widely used in veterinary and human medicine. Other uses are as an analytical reagent, food additives (e.g. sodium aluminium phosphate as anticaking agent) and in cosmetic preparations (aluminium chloride). Aluminium distearate is used for thickening lubricating oils. Aluminium hydroxide acetate and phosphate are antacids with common indications in veterinary medicine: gastric hyperacidity, peptic ulcer, gastritis and reflux esophagitis. A major use of antacids in veterinary medicine is in treatment and prevention of ruminal acidosis from grain overload, adsorbent and antidiarrheal. The dosage of aluminium hydroxide is 30 g/animal in cattle and 2 g/animal in calves and foals. Gel preparations contain approximately 4% aluminium hydroxide. Aluminium potassium sulphate is used topically as a antiseptic, astringent (i.e. washes, powders, and ‘leg tighteners’ for horses (30 to 60 g/animal) and antimycotic (1% solution for dipping or spraying sheeps with dermatophilus mycotic dermatitis). In cattle it is occasionally used for stomatitis and vaginal and intrauterine therapy at doses of 30 to 500 g/animal. In human medicine, aluminium hydroxide-based preparations have a widespread use in gastroenterology as antacids (doses of about 1 g/person orally) and as phosphate binders (doses of about 0.8 g/person orally) in patients an impairment of renal function. -

Ep 3106176 B1

(19) TZZ¥_Z__T (11) EP 3 106 176 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 39/12 (2006.01) A61K 39/39 (2006.01) 11.10.2017 Bulletin 2017/41 (21) Application number: 16183076.5 (22) Date of filing: 06.12.2012 (54) ALUMINIUM COMPOUNDS FOR USE IN THERAPEUTICS AND VACCINES ALUMINIUMVERBINDUNGEN ZUR VERWENDUNG FÜR THERAPEUTIKA UND IMPFSTOFFE COMPOSÉS D’ALUMINIUM POUR UTILISATION DANS DES PRODUITS THÉRAPEUTIQUES ET VACCINS (84) Designated Contracting States: (56) References cited: AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB WO-A2-2009/158284 US-A1- 2005 158 334 GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR • SRIVASTAVA A K ET AL: "A purified inactivated Japaneseencephalitis virus vaccine made in vero (30) Priority: 06.12.2011 EP 11192230 cells", VACCINE, vol. 19, no. 31, 14 August 2001 13.03.2012 PCT/EP2012/054387 (2001-08-14), pages 4557-4565, XP027321987, ELSEVIER LTD, GB ISSN: 0264-410X [retrieved (43) Date of publication of application: on 2001-08-14] 21.12.2016 Bulletin 2016/51 • ANONYMOUS: "Rehydragel Adjuvants. Product profile", General Chemical , 2008, pages 1-2, (60) Divisional application: XP002684848, Retrieved from the Internet: 17185526.5 URL:http://www.generalchemical.com/assets/ pdf/Rehydragel_Adjuvants_Product_Profile.p df (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in [retrieved on 2012-10-08] accordance with Art. 76 EPC: • LINDBLAD, EB: "Special feature. Aluminium 12795830.4 / 2 788 023 compoundsfor usein vaccines", IMMUNOL. -

Midas Arsine

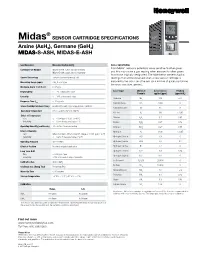

® Midas SENSOR CARTRIDGE SPECIFICATIONS Arsine (AsH3), Germane (GeH4) MIDAS-S-ASH, MIDAS-E-ASH Gas Measured Measured Arsine (AsH3) Cross Sensitivities Each Midas® sensor is potentially cross sensitive to other gases Cartridge Part Number MIDAS-S-ASH 1 year standard warranty MIDAS-E-ASH 2 year extended warranty and this may cause a gas reading when exposed to other gases than those originally designated. The table below presents typical Sensor Technology 3 electrode electrochemical cell readings that will be observed when a new sensor cartridge is Measuring Range (ppm) AsH 0 – 0.2ppm exposed to the cross sensitive gas (or a mixture of gases containing 3 the cross sensitive species). Minimum Alarm 1 Set Point 0.025ppm Gas / Vapor Chemical Concentration Reading Repeatability < ± 2% of measured value Formula applied (ppm) (ppm AsH3) Linearity < ± 10% of measured value Ammonia NH3 108 <0.1 Response Time t62.5 < 15 seconds Carbon Dioxide CO2 5,000 0 Sensor Cartridge Life Expectancy ≥ 24 months under typical application conditions Carbon Monoxide CO 85 0 Operating Temperature 0°C to + 40°C (32°C to 104°F) Chlorine CI2 TBD <-0.05 Effect of Temperature Diborane B2H6 0.1 0.05 Zero < ± 0.004 ppm / °C (0° to 40°C) Sensitivity < ± 0.9% of measured value / °C Disilane Si2H6 0.27 0.12 Operating Humidity (continuous) 10 – 95% rH non-condensing Germane GeH4 0.27 0.05 Effect of Humidity Hydrogen H2 3100 <-0.05 Zero Initial short term drift at abrupt rH change (< 0.001 ppm / % rH) Sensitivity < ± 0.2% of measured value / % rH Hydrogen Chloride HCI 7.9 0 -

Flow Injection Electrochemical Hydride Generation of Hydrogen Selenide on Lead Cathode: Critical Study of the Influence of Experimental Parameters

ANALYTICAL SCIENCES MARCH 2003, VOL. 19 367 2003 © The Japan Society for Analytical Chemistry Flow Injection Electrochemical Hydride Generation of Hydrogen Selenide on Lead Cathode: Critical Study of the Influence of Experimental Parameters Eduardo BOLEA, Francisco LABORDA,† and Juan R. CASTILLO Analytical Spectroscopy and Sensors Group, Department of Analytical Chemistry, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain A flow injection system for the determination of selenium by electrochemical hydride generation and quartz tube atomic absorption spectrometry is described. The generator consists of an electrolytic flow-through cell with a concentric arrangement and a packed cathode made of particulated lead. The influences of sample flow rate, carrier gas flow rate and electrolysis current on the hydrogen selenide generation have been critically studied. Both sample flow rate and electrolysis current play important roles in the efficiency of the hydride generation process. A characteristic mass of 2.4 ng and a concentration detection limit of 17 µg l–1 were obtained for a sample volume of 420 µl. (Received January 22, 2002; Accepted September 25, 2002) The electrochemical generation of different hydrides on lead Introduction cathodes, the material that offers the highest hydrogen overpotential among those commonly used, has been studied by The formation of volatile covalent hydrides of a number of several authors.3–5,7–11 Sand3 and Thompson4,5 obtained elements (As, Bi, Ge, Sn, Sb, Se, Te and Pb) by reaction with generation efficiencies of 100%, whereas efficiencies of 86,11 sodium tetrahydroborate in acidic media has been widely used 928 and 60%11 were obtained for arsine, stibine and hydrogen for sample introduction in atomic spectrometry. -

A Review of the Structural Architecture of Tellurium Oxycompounds

Mineralogical Magazine, May 2016, Vol. 80(3), pp. 415–545 REVIEW OPEN ACCESS A review of the structural architecture of tellurium oxycompounds 1 2,* 3 A. G. CHRISTY ,S.J.MILLS AND A. R. KAMPF 1 Research School of Earth Sciences and Department of Applied Mathematics, Research School of Physics and Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 2 Geosciences, Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666, Melbourne, Victoria 3001, Australia 3 Mineral Sciences Department, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90007, USA [Received 24 November 2015; Accepted 23 February 2016; Associate Editor: Mark Welch] ABSTRACT Relative to its extremely low abundance in the Earth’s crust, tellurium is the most mineralogically diverse chemical element, with over 160 mineral species known that contain essential Te, many of them with unique crystal structures. We review the crystal structures of 703 tellurium oxysalts for which good refinements exist, including 55 that are known to occur as minerals. The dataset is restricted to compounds where oxygen is the only ligand that is strongly bound to Te, but most of the Periodic Table is represented in the compounds that are reviewed. The dataset contains 375 structures that contain only Te4+ cations and 302 with only Te6+, with 26 of the compounds containing Te in both valence states. Te6+ was almost exclusively in rather regular octahedral coordination by oxygen ligands, with only two instances each of 4- and 5-coordination. Conversely, the lone-pair cation Te4+ displayed irregular coordination, with a broad range of coordination numbers and bond distances. -

Standard Thermodynamic Properties of Chemical

STANDARD THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES ∆ ° –1 ∆ ° –1 ° –1 –1 –1 –1 Molecular fH /kJ mol fG /kJ mol S /J mol K Cp/J mol K formula Name Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Ac Actinium 0.0 406.0 366.0 56.5 188.1 27.2 20.8 Ag Silver 0.0 284.9 246.0 42.6 173.0 25.4 20.8 AgBr Silver(I) bromide -100.4 -96.9 107.1 52.4 AgBrO3 Silver(I) bromate -10.5 71.3 151.9 AgCl Silver(I) chloride -127.0 -109.8 96.3 50.8 AgClO3 Silver(I) chlorate -30.3 64.5 142.0 AgClO4 Silver(I) perchlorate -31.1 AgF Silver(I) fluoride -204.6 AgF2 Silver(II) fluoride -360.0 AgI Silver(I) iodide -61.8 -66.2 115.5 56.8 AgIO3 Silver(I) iodate -171.1 -93.7 149.4 102.9 AgNO3 Silver(I) nitrate -124.4 -33.4 140.9 93.1 Ag2 Disilver 410.0 358.8 257.1 37.0 Ag2CrO4 Silver(I) chromate -731.7 -641.8 217.6 142.3 Ag2O Silver(I) oxide -31.1 -11.2 121.3 65.9 Ag2O2 Silver(II) oxide -24.3 27.6 117.0 88.0 Ag2O3 Silver(III) oxide 33.9 121.4 100.0 Ag2O4S Silver(I) sulfate -715.9 -618.4 200.4 131.4 Ag2S Silver(I) sulfide (argentite) -32.6 -40.7 144.0 76.5 Al Aluminum 0.0 330.0 289.4 28.3 164.6 24.4 21.4 AlB3H12 Aluminum borohydride -16.3 13.0 145.0 147.0 289.1 379.2 194.6 AlBr Aluminum monobromide -4.0 -42.0 239.5 35.6 AlBr3 Aluminum tribromide -527.2 -425.1 180.2 100.6 AlCl Aluminum monochloride -47.7 -74.1 228.1 35.0 AlCl2 Aluminum dichloride -331.0 AlCl3 Aluminum trichloride -704.2 -583.2 -628.8 109.3 91.1 AlF Aluminum monofluoride -258.2 -283.7 215.0 31.9 AlF3 Aluminum trifluoride -1510.4 -1204.6 -1431.1 -1188.2 66.5 277.1 75.1 62.6 AlF4Na Sodium tetrafluoroaluminate -

Structural Inorganic Chemistry

Structural Inorganic Chemistry A. F. WELLS FIFTH EDITION \ CLARENDON PRESS • OXFORD Contents ABBREVIATIONS xxix PARTI 1. INTRODUCTION 3 The importance of the solid State 3 Structural formulae of inorganic Compounds 11 Geometrical and topological limitations on the structures of v molecules and crystals 20 The complete structural chemistry of an element or Compound 23 Structure in the solid State 24 Structural changes on melting 24 Structural changes in the liquid State 25 Structural changes on boiling or Sublimation 26 A Classification of crystals 27 Crystals consisting of infinite 3-dimensional complexes 29 Layer structures 30 Chain structures 33 Crystals containing finite complexes 36 Relations between crystal structures 36 2. SYMMETRY 38 Symmetry elements 38 Repeating patterns, unit cells, and lattices 38 One- and two-dimensional lattices; point groups 39 Three-dimensional lattices; space groups 42 Point groups; crystal Systems 47 Equivalent positions in space groups 50 Examples of 'anomalous' symmetry 5 1 Isomerism 52 Structural (topological) isomerism 54 Geometrical isomerism 56 Optical activity 57 3. POLYHEDRA AND NETS 63 Introduction 63 The basic Systems of connected points 65 viii Contents Polyhedra 68 Coordination polyhedra: polyhedral d'omains 68 The regulär solids 69 Semi-regular polyhedra 71 Polyhedra related to the pentagonal dodecahedron and icosahedron 72 Some less-regular polyhedra 74 5-coordination 76 7-coordination 77 8-coordination 78 9-coordination 79 10-and 11-coordination 80 Plane nets 81 Derivation of plane nets