The Regulation of Investment Funds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Companies That Made a Full-Time O Er to One Or More MSOR/IE Students

Companies that made a full-time oer to one or more MSOR/IE students who graduated in October 2019 or February 2020 26% Data Science & Business Analytics Firms include: Amazon, Wayfair, 360i, AccrueMe LLC, Amadeus, American Express, Amherst Holdings, Aretove Technologies, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Capgemini, Cubesmart, DIA Associates, Expedia, Goldenberry, LLC, Intellinum Analytics Inc, Jellysmack, Kalo Inc, LGO Markets, Ly, Mediacom, NBCUniversal Media, LLC, Neuberger Berman, PepsiCo, Amazon, Robinhood, Shareablee, State Administration of Foreign Exchange, Swiss Re, Two Sigma, Whiterock AI Titles include: Big Data Analyst, Business Analyst, Business Intelligence Analyst, Credit Risk Analyst, Data Analyst, Data Engineer, Data Scientist, Insight Analyst, Investment Analytics Analyst, Quant Researcher/Developer, Quantitative Analytics Associate, Research Analyst and Solutions Engineer 20% Quantitative Research Firms include: Citi, Goldman Sachs, Aflac Global Investments, American Express, Arrowstreet Capital, CME Group, Credit Agricole, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, Global A.I., Jp Morgan Chase, Krane Funds Advisors, New York International Capital, PingAn Technology Inc., Puissance Capital, Rayens Capital, SG Americas Securities LLC, Shanghai Kingstar Soware Technology Co., Ltd., Vidrio FInancial, Wolfe Research Titles include: Analyst, Applied Quantitative Research & Development, Associate Vice President, CFR Senior Analyst, Consumer & Investment Management Senior Analyst, Data Modeling Analyst, FICC Strategic Analyst, Investment Analyst, Markets Quantitative Analyst, Post Trade & Optimization Services Quant Risk Manager, Quantitative Analyst, Quantitative Associate, Quantitative Strategist, Quantitative Strategist Associate, Quantitative Strategy & Modeling, Risk Appetite Model & Methodology Analyst, Securitization Quant, Sell Side M&A Investment Banking Analyst and Treasury/CIO Senior Associate 19% Engineering & Technology Firms include: Alibaba, Amazon, Anheuser-Busch InBev, AntX LLC, Baco SA,Beijing Huahui Shengshi Energy Technology Co. -

Capital Markets

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Capital Markets OCTOBER 2017 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Capital Markets Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Brian Smith and Amyn Moolji, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, John Dolan, Rebekah Goshorn, Alexander Jackson, W. Moses Kim, John McGrail, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bill Pelton, Fred Pietrangeli, Frank Ragusa, Jessica Renier, Lori Santamorena, Christopher Siderys, James Sonne, Nicholas Steele, Mark Uyeda, and Darren Vieira. iii A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities • Capital Markets Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Scope of This Report 3 Review of the Process for This Report 4 The U.S. Capital Markets 4 Summary of Issues and Recommendations 6 Capital Markets Overview 11 Introduction 13 Key Asset Classes 13 Key Regulators 18 Access to Capital 19 Overview and Regulatory Landscape 21 Issues and Recommendations 25 Equity Market Structure 47 Overview and Regulatory Landscape 49 Issues and Recommendations 59 The Treasury Market 69 Overview and Regulatory Landscape 71 Issues and Recommendations 79 -

Phi Beta Kappa Number

Phi Beta Kappa Number ~ DECEMRER, 1918 I 3 --/ Sigtna Kappa Triangle VOL. XIII DECEMBER, 1918 NO. 1 ... , ~' • 'Ev KTJP p.ta ooo~.. OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF SIGMA KAPPA SORORITY PHI BETA KAPPA NUMBER GEORGE BANTA, Official Printer and Publisher 450 to 454 Ahnaip St., Menasha, Wlsconein. TRIANGLE DIRECTORY Editor-in-chief MRS. FRANCIS MARSHALL WIGMORE c!o The Orland Register, Orland, Cal. Chapter Editor FRITZI NEUMANN 701 A St. S. E., Washington, D. C. Alumnm Editor FLORENCE SARGENT CARLL South China, Maine . Exchange Editor MABEL GERTRUDE MATTOON 127 N. Malabar St., Huntington Park, Cal. Contributing Editor GRACE COBURN SMITH 2137 Bancroft St., Washington, D. C. Circulation Manager HATTIE MAY BAKER 24 Sunset Road, West Somerville, Mass. All communications r egarding subscriptions should be sent direct to Miss Baker. SIGMA KAPPA TRIANGLE is issued m December, March, June, and September. All chapters, active and alumnre, must send all manuscript to their respective editors (at the addresses given above) on or before the Fifteenth of October, J anuary, April, and July. Price $1.25 per annum. Single copies 35 cents. Entered as second-cia s matter October 15, 1910, at the postoffice at Menasha, Wis., under the act of March 3, 1879. Acceptance for mailing at special rate of postage provided f or in section 1103, Act of October 3, 1917, authorized, .July 31, 1918. SIGMA KAPPA SORORITY Founded at Colby College in 1874 FOUNDERS MRS. L. D. CARVER, nee Mary Caffrey Lowe, 26 Gurney St., Cam bridge, Mass. ELIZABETH GORHAM HOAG (deceased). MRS. J. B. PIERCE, nee Ida M. Fuller, 201 Linwood Blvd., Kansas City, Mo. -

The Quants Run Wall Street Now - WSJ 5/24/17, 11:08 AM

The QuantsTHE Run Wall Street Now - WSJ QUANTS RUN5/24/17, 11:08 AM WALL STREET SHARE NOW For decades, investors imagined a time when data-driven traders would dominate financial markets. That day has arrived. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-quants-run-wall-street-now-1495389108 Page 1 of 14 The Quants Run Wall Street Now - WSJ 5/24/17, 11:08 AM BY GREGORY ZUCKERMAN AND BRADLEY HOPE Alexey Poyarkov, a former gold-medal winner of the International Mathematical Olympiad for high-school students, spent most of his early career honing algorithms ? at technology companies such as Microsoft Corp. , where he helped make the Bing search engine smarter at ferreting out pornography. Last year, a bidding war for Mr. Poyarkov broke out among hedge-fund heavyweights Renaissance Technologies LLC, Citadel LLC and TGS Management Co. When it was over, he went to work at TGS in Irvine, Calif., and could earn as much as $700,000 in his first year, say people familiar with the contract. The Russian-born software engineer, who declined to comment, as did the hedge funds, had almost no financial experience. What TGS wanted was his wizardry at designing algorithms, sets of rules used to power calculations and problem- solving, which in the investment world can quickly parse data and decide what to buy and sell, often with little human involvement. Up and down Wall Street, algorithmic-driven trading WSJ PODCAST and the quants who use sophisticated statistical models to find attractive trades are taking over the The Quants: Today’s Kings investment world. -

Skin Or Skim? Inside Investment and Hedge Fund Performance

Skin or Skim?Inside Investment and Hedge Fund Performance∗ Arpit Guptay Kunal Sachdevaz September 7, 2017 Abstract Using a comprehensive and survivor bias-free dataset of US hedge funds, we docu- ment the role that inside investment plays in managerial compensation and fund per- formance. We find that funds with greater investment by insiders outperform funds with less “skin in the game” on a factor-adjusted basis, exhibit greater return persis- tence, and feature lower fund flow-performance sensitivities. These results suggest that managers earn outsize rents by operating trading strategies further from their capac- ity constraints when managing their own money. Our findings have implications for optimal portfolio allocations of institutional investors and models of delegated asset management. JEL classification: G23,G32,J33,J54 Keywords: hedge funds, ownership, managerial skill, alpha, compensation ∗We are grateful to our discussant Quinn Curtis and for comments from Yakov Amihud, Charles Calomiris, Kent Daniel, Colleen Honigsberg, Sabrina Howell, Wei Jiang, Ralph Koijen, Anthony Lynch, Tarun Ramado- rai, Matthew Richardson, Paul Tetlock, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Jeffrey Wurgler, and seminar participants at Columbia University (GSB), New York University (Stern), the NASDAQ DRP Research Day, the Thirteenth Annual Penn/NYU Conference on Law and Finance, Two Sigma, IRMC 2017, the CEPR ESSFM conference in Gerzensee, and the Junior Entrepreneurial Finance and Innovation Workshop. We thank HFR, CISDM, eVestment, BarclaysHedge, and Eurekahedge for data that contributed to this research. We gratefully acknowl- edge generous research support from the NYU Stern Center for Global Economy and Business and Columbia University. yNYU Stern School of Business, Email: [email protected] zColumbia Business School, Email: [email protected] 1 IIntroduction Delegated asset managers are commonly seen as being compensated through fees imposed on outside investors. -

Staff Report on Algorithmic Trading in U.S. Capital Markets

Staff Report on Algorithmic Trading in U.S. Capital Markets As Required by Section 502 of the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act of 2018 This is a report by the Staff of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The Commission has expressed no view regarding the analysis, findings, or conclusions contained herein. August 5, 2020 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Congressional Mandate ......................................................................................................................... 3 B. Overview ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 C. Algorithmic Trading and Markets ..................................................................................................... 5 II. Overview of Equity Market Structure .................................................................................................. 7 A. Trading Centers ........................................................................................................................................ 9 B. Market Data ............................................................................................................................................. 19 III. Overview of Debt Market Structure ................................................................................................. -

Skin Or Skim? Inside Investment and Hedge Fund Performance

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SKIN OR SKIM? INSIDE INVESTMENT AND HEDGE FUND PERFORMANCE Arpit Gupta Kunal Sachdeva Working Paper 26113 http://www.nber.org/papers/w26113 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 July 2019 We would like to thank Jules Van Binsbergen, Maria Chaderina, Quinn Curtis, Nickolay Gantchev, Qiping Huang, Clemens Sialm, Lin Sun, and Sumudu Watugala (discussants). We have also benefited from discussions with Simona Abis, Yakov Amihud, Charles Calomiris, Alan Crane, Kent Daniel, Colleen Honigsberg, Sabrina Howell, Wei Jiang, Ralph Koijen, Anthony Lynch, Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, Tarun Ramadorai, Matthew Richardson, Paul Tetlock, James Weston, and Jeffrey Wurgler, as well as seminar participants at Berkeley (Haas), Columbia University (GSB), New York University (Stern), University of Pennsylvania (Wharton), Rice University (Jones), Yale University (SOM), NBER Long-Term Asset Management, the NASDAQ DRP Research Day, the 13th Annual Penn/NYU Conference on Law and Finance, IRMC, the CEPR ESSFM conference in Gerzensee, the Junior Entrepreneurial Finance and Innovation Workshop, the Hedge Fund Research Symposium, the 10th Hedge Fund and Private Equity Conference, the University of Kentucky Finance Conference, FIRS, MFA, NFA, SFS Cavalcade, Two Sigma, Q Group. We thank HFR, CISDM, eVestment, BarclayHedge, and Eurekahedge for data that contributed to this research. We gratefully acknowledge generous research support from the NYU Stern Center for Global Economy and Business and Columbia University. We thank Billy Xu for excellent research assistance. See https://www.skinorskim.org for Form ADV data used in this paper. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

The $1Bn Club: Largest Hedge Fund Managers Download Data

View the full edition of Spotlight at: https://www.preqin.com/docs/newsletters/hf/Preqin-Hedge-Fund-Spotlight-May-2016.pdf ê Feature Article The $1bn Club: Largest Hedge Fund Managers Download Data The $1bn Club: Largest Hedge Fund Managers This month, Janet Chambers takes a look at the ‘$1bn Club’, a group of the world’s largest hedge fund managers. In the 12 months since Preqin’s last $1bn Club report, there have been significant changes to the make-up of the group, not least the 170 hedge fund managers entering the club. Following an underwhelming 2015 managers that have experienced a Inside the $1bn Club and a slow start to 2016 in terms of steady growth in AUM. This article looks performance, hedge fund managers at the current make-up of the $1bn Club Managers with $20bn or more in AUM have experienced two consecutive and how it has changed over the past have seen their assets decline by 15% quarters of net outfl ows to Q1 2016 year. since May 2015, implying that even (see page 6). However, one group of the elite have not been immune to managers that continues to dominate Preqin’s Hedge Fund Online currently redemptions from institutional investors the assets of the hedge fund industry is details 668 managers with at least $1bn over the past 12 months. Bridgewater the $1bn Club – hedge fund managers in AUM, with the club increasing by Associates maintains its position as the with at least $1bn in assets under a net 98 members over the past year. -

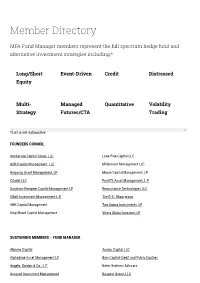

Member Directory

Member Directory MFA Fund Manager members represent the full spectrum hedge fund and alternative investment strategies including:* Long/Short Event-Driven Credit Distressed Equity Multi- Managed Quantitative Volatility Strategy Futures/CTA Trading *List is not exhaustive FOUNDERS COUNCIL Anchorage Capital Group, LLC Lone Pine Capital LLC AQR Capital Management, LLC Millennium Management LLC Balyasny Asset Management, LP Moore Capital Management, LP Citadel LLC Point72 Asset Management, L.P. Davidson Kempner Capital Management LP Renaissance Technologies LLC Elliott Investment Management L.P. The D. E. Shaw group HBK Capital Management Two Sigma Investments, LP King Street Capital Management Viking Global Investors LP SUSTAINING MEMBERS – FUND MANAGER Abrams Capital Axonic Capital LLC Alphadyne Asset Management LP Bain Capital Credit and Public Equities Angelo, Gordon & Co., L.P. Baker Brothers Advisors Assured Investment Management Baupost Group, LLC BlackRock Alternative Investors IONIC Capital Management LLC Bracebridge Capital, LLC Junto Capital Management LP Bridgewater Associates, LP. Kensico Capital Management Brigade Capital Management, LP Kepos Capital LP Cadian Capital Management Kingdon Capital Management, LLC Campbell & Company, LP Laurion Capital Management LP Capula Investment Management LLP Magnetar Capital LLC CarVal Investors Man Group Casdin Capital Marathon Asset Management, L.P. Castle Hook Partners LP Marshall Wace North America LP Centerbridge Partners, L.P. Melvin Capital CIFC Asset Management Meritage Group LP Coatue Management LLC Millburn Ridgeeld Corporation D1 Capital Partners MKP Capital Management Diameter Capital Partners LP Monarch Alternative Capital LP EJF Capital, LLC Napier Park Global Capital Element Capital Management LLC One William Street Capital Management LP Eminence Capital, LP P. Schoenfeld Asset Management LP Empyrean Capital Partners, LP Palestra Capital Management LLC Emso Asset Management Limited Paloma Partners Management Company ExodusPoint Capital Management, LP PAR Capital Management, Inc. -

What We Learned from Kaggle Two-Sigma News Sentiment Competition?

What we learned from Kaggle Two Sigma News Competition Ernie Chan, Ph.D. and Roger Hunter, Ph.D. QTS Capital Management, LLC. The Competition • Kaggle hosts many data science competitions – Usual input is big data with many features. – Usual tool is machine learning (but not required). • Two Sigma Investments is a quantitative hedge fund with AUM > $42B. – Sponsored Kaggle news competition starting Sept, 2018, ending July, 2019. – Price, volume, and residual returns data for about 2,000 US stocks starting 2007. – Thomson-Reuters news sentiment data starting 2007. – Evaluation criterion: Sharpe ratio of a user-constructed market (beta)-neutral portfolio*. Our Objectives • Does news sentiment generate alpha? – Find out using normally expensive, high quality data. • Does machine learning work out-of-sample? • Does successful ML == successful trading strategy? • How best to collaborate in a financial data science project? • Educational: example lifecycle of trading strategies development using data science and ML. Constraints • All research must be done in cloud-based Kaggle kernel using Jupyter Notebook. – Only 4 CPU’s, limited memory and slow. – Kernel killed after a few idle hours. – Cannot download data for efficient analysis. – Cannot upload any supplementary data to kernel (E.g. ETF prices). – Poor debugging environment (it is Jupyter Notebook!) – Lack of “securities master database” for linking stocks data. Features • Unadjusted open, close, volume, 1- and 10- day raw and residual returns. – Jonathan Larkin[1] designed PCA to show that residual returns = raw returns - β* market returns = CAPM residual returns [1] www.kaggle.com/marketneutral/eda-what-does-mktres-mean • News sentiment, relevance, novelty, subjects, audiences, headline, etc. -

Here Are 5 Questions from the Momath Masters Contest

Are You Smarter Than a Quant? Here Are 5 Questions from the MoMath Masters Contest Two Sigma Investments co- founder John Overdeck competes in the 2016 MoMath Masters competition PHOTO: NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MATHEMATICS By BRADLEY HOPE Mar 4, 2016 11:02 am ET The quants have been performing especially well in this year’s choppy markets. How do they do it? You won’t hear any of the brainiacs at firms such as Renaissance Technologies and Two Sigma Investments giving away any secrets. Hedge funds that use largely quantitative strategies are notoriously secretive about their algorithms. But a few times a year, the top quants get together to compete over math puzzles for the good of charity or the National Museum of Mathematics in Manhattan. Last week, the museum held its 2016 MoMath Masters competition. The overall winner was Po-Shen Loh, a Carnegie Mellon math professor. In second place was Two Sigma’s Daniel Stronger, a quantitative analyst with a Ph.D. in computer science, and in third was Ken Perlin, a computer science professor at New York University who invented something called “Perlin noise” that makes textures look realistic in computer games. Winner of the Math Classics category – which has famous, old puzzles – was Geva Patz, co-founder of an automated options trading firm called Android Alpha Fund LLC (and a part-time “pyrotechnician” for Grucci fireworks, according to his Linkedin page). Patrick Huggins, a quantitative researcher at Citadel Investment Group, won the “Gardner Greats” category – named after the famous math puzzler Martin Gardner. And the winner of the Math Pulse category, which has math questions from popular culture, was Satish Ramakrishna, global head of prime finance risk and pricing at Deutsche Bank. -

Haoxiang Zhu

Haoxiang Zhu MIT Sloan School of Management Email: [email protected] 100 Main Street, E62-623 Web: www.mit.edu/~zhuh Cambridge, MA 02142 Telephone: +1 617-253-2478 Education 2012 PhD in Finance, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University 2006 B.A. Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Oxford (First Class Honors) Academic Appointments 2012| MIT Sloan School of Management { Gordon Y Billard Professor of Management and Finance, 2020| { Associate Professor of Finance (with tenure), 2019| { Associate Professor of Finance (without tenure), 2017{19 { Sarofim Family Career Development Professor, 2016{20 { Assistant Professor of Finance, 2012{17 2014| National Bureau of Economic Research { Research Associate, 2019| { Faculty Research Fellow, 2014{19 2020| Faculty Affiliate, MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering 2020| Faculty Affiliate, MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy Research Interests Asset Pricing, Market Structure, Market Design Editorial Positions 2019| Finance Department Editor, Management Science (Associate Editor, 2018-19) 2018| Associate Editor, Journal of Finance Honors and Awards 2017 Amundi Smith Breeden Prize (First Prize), Journal of Finance 2016 First Prize, AQR Insight Award Poets and Quants Best 40 Under 40 Business School Professors Special Mention, Federation of European Securities Exchanges Joseph de la Vega Prize Best Discussant, University of Washington Summer Finance Conference 2015 Kepos Capital Award for Best Paper on Investments, Western Finance Association TCW Best Paper Award, China International Conference in Finance Best Paper Award, Finance Down Under conference 1 2013 Review of Financial Studies Young Researcher Prize Yihong Xia Best Paper Award, China International Conference in Finance 2012 Michael Brennan Best Paper Award, Review of Asset Pricing Studies 2011 First Prize, Morgan Stanley Prize for Excellence in Financial Markets Research Publications (in reverse chronological order) 17.