World Heritage Papers 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First Name Surname

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 20/02/20 you will not appear on this list, an updated version will be put online on or around the 28/02/20. Runners cannot move into an earlier wave, but you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. If you have any problems, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950. COLOUR RACE APPROX TO THE START WAVE NO. START TIME 1 BLUE A 09:10 2 RED A 09:10 3 PINK A 09:15 4 GREEN A 09:20 5 BLUE B 09:32 6 RED B 09:36 7 PINK B 09:40 8 GREEN B 09:44 9 BLUE C 09:48 10 RED C 09:52 11 PINK C 09:56 12 GREEN C 10:00 VIP BLACK Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First name Surname 11 Pink 1889 Rebecca Aarons Any Black 1890 Jakob Abada 2 Red 4 Susannah Abayomi 3 Pink 1891 Yassen Abbas 6 Red 1892 Nick Abbey 10 Red 1823 Hannah Abblitt 10 Red 1893 Clare Abbott 4 Green 1894 Jon Abbott 8 Green 1895 Jonny Abbott 12 Green 11043 Pamela Abbott 6 Red 11044 Rebecca Abbott 11 Pink 1896 Leanne Abbott-Jones 9 Blue 1897 Emilie Abby Any Black 1898 Jennifer Abecina 6 Red 1899 Philip Abel 7 Pink 1900 Jon Abell 10 Red 600 Kirsty Aberdein 6 Red 11045 Andrew Abery Any Black 1901 Erwann ABIVEN 11 Pink 1902 marie joan ablat 8 Green 1903 Teresa Ablewhite 9 Blue 1904 Ahid Abood 6 Red 1905 Alvin Abraham 9 Blue 1906 Deborah Abraham 6 Red 1907 Sophie Abraham 1 Blue 11046 Mitchell Abrams 4 Green 1908 David Abreu 11 Pink 11047 Kathleen Abuda 10 Red 11048 Annalisa Accascina 4 Green 1909 Luis Acedo 10 Red 11049 Vikas Acharya 11 Pink 11050 Catriona Ackermann -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)»

MINISTERE DE LA CULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI *********** Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi DIRECTION NATIONALE DU ********** PATRIMOINE CULTUREL ********** RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT DE CONSERVATION DU SITE «FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (Pays Dogon)» Janvier 2020 RAPPORT SUR L’ETAT ACTUEL DE CONSERVATION FALAISES DE BANDIAGARA (PAYS DOGON) (MALI) (C/N 516) Introduction Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est inscrit sur la Liste du Patrimoine Mondial de l’UNESCO en 1989 pour ses paysages exceptionnels intégrant de belles architectures, et ses nombreuses pratiques et traditions culturelles encore vivaces. Ce Bien Mixte du Pays dogon a été inscrit au double titre des critères V et VII relatif à l’inscription des biens: V pour la valeur culturelle et VII pour la valeur naturelle. La gestion du site est assurée par une structure déconcentrée de proximité créée en 1993, relevant de la Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel (DNPC) du Département de la Culture. 1. Résumé analytique du rapport Le site « Falaises de Bandiagara » (Pays dogon) est soumis à une rude épreuve occasionnée par la crise sociopolitique et sécuritaire du Mali enclenchée depuis 2012. Cette crise a pris une ampleur particulière dans la Région de Mopti et sur ledit site marqué par des tensions et des conflits armés intercommunautaires entre les Dogons et les Peuls. Un des faits marquants de la crise au Pays dogon est l’attaque du village d’Ogossagou le 23 mars 2019, un village situé à environ 15 km de Bankass, qui a causé la mort de plus de 150 personnes et endommagé, voire détruit des biens mobiliers et immobiliers. -

Cultural Impacts of Tourism: the Ac Se of the “Dogon Country” in Mali Mamadou Ballo

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 2010 Cultural impacts of tourism: The ac se of the “Dogon Country” in Mali Mamadou Ballo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Ballo, Mamadou, "Cultural impacts of tourism: The case of the “Dogon Country” in Mali" (2010). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM: The case of the “Dogon Country” in Mali A Thesis presented to the faculty in the College of Applied Science and Technology School of Hospitality and Service Management at Rochester Institute of Technology By Mamadou Ballo Thesis Supervisor Richard Rick Lagiewski Date approved:______/_______/_______ February 2010 VâÄàâÜtÄ \ÅÑtvàá Éy gÉâÜ|áÅM vtáx Éy WÉzÉÇá |Ç `tÄ| TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Abstract…………………………………………………..……….………………………………7 Introduction…………………………………………………………..……………………………9 1.1. Background: overview of tourism in Mali…………………….….…..………………………9 1.2. Purpose of the study…………………………………………………...………….…………13 1.3. Significance of the study………………………..……………………...……………………13 1.4. Definition of key terms…………………………………………………...…………………14 CHAPTER 2 Literature Review…………………………………….……….………….………………………15 CHAPTER 3 Methodology……………………………….……………………………………………………28 3.1. Description of the sample………………………...…………………………………………29 3.2. Language…………….…………………………...………………………….………………30 3.3. Scope and limitations……………………...……………………………...…………………30 3.4. Weakness of the study………………………..…………………………….………………30 3.5. Research questions …………………………………..……………………..………………30 CHAPTER 4 Results analysis…………………………………………………………………………………..31 CHAPTER 5 Conclusions and Recommendations …………….………………………………………………56 5.1. Major findings …………………………...….………………………………………………56 5.2. -

Inventaire Des Aménagements Hydro-Agricoles Existants Et Du Potentiel Amenageable Au Pays Dogon

INVENTAIRE DES AMÉNAGEMENTS HYDRO-AGRICOLES EXISTANTS ET DU POTENTIEL AMENAGEABLE AU PAYS DOGON Rapport de mission et capitalisation d’expérienCe Financement : Projet d’Appui de l’Irrigation de Proximité (PAIP) Réalisation : cellule SIG DNGR/PASSIP avec la DRGR et les SLGR de la région de Mopti Bamako, avril 2015 Table des matières I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 II. Méthodologie appliquée ................................................................................................................ 3 III. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Bandiagara .......... 4 1. Déroulement des activités dans le cercle de Bandiagara ................................................................................... 7 2. Bilan de l’inventaire du cercle de Bandiagara .................................................................................................... 9 IV. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans les cercles de Bankass et Koro 9 1. Déroulement des activités dans les deux cercles ............................................................................................... 9 2. Bilan de l’inventaire pour le cercle de Koro et Bankass ................................................................................... 11 Gelöscht: 10 V. Inventaire des AHA existants et du potentiel aménageable dans le cercle de Douentza ............. 12 VI. Récapitulatif de l’inventaire -

WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History

WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History Introduced by BRIJ LAL Working Paper Series Pacific Islands Studies Program Centers for Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa EDITOR'S OOTE Brij Lal's introduction discusses both the history of the teaching of Pacific Islands history at the University of Hawaii and the origins and background of this particular working paper. Lal's comments on this working paper are quite complete and further elaboration is not warranted. Lal notes that in the fall semester of 1983, both he and David Hanlon were appointed to permanent positions in Pacific history in the Department of History. What Lal does not say is that this represented a monumental shift of priorities at this University. Previously, as Lal notes, Pacific history was taught by one individual and was deemed more or less unimportant. The sole representative maintained a constant struggle to keep Pacific history alive, but the battle was always uphill. The year 1983 was a major, if belated, turning point. Coinciding with a national recognition that the Pacific Islands could no longer be ignored, the Department of History appointed both Lal and Hanlon as assistant professors. The two have brought a new life to Pacific history at this university. New courses and seminars have been added, and both men have attracted a number of new students. The University of Hawaii is the only American university that devotes serious attention to Pacific history. Robert,C. Kiste Director Center for Pacific Islands Studies WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History Introduced by BRIJ V. LAL 1987 " TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Photos & Text : Huib Blom Sketches : Arian & Anneke Blom

www.dogon-lobi.ch photos & text : Huib Blom sketches : Arian & Anneke Blom Table of contents Introduction 01 Toloy 02 Tellem 02 Nongo 03 Dogon Country 05 Niongono (Pignari) 06 Kargue (Lowel-Gueou) 07 Dani Sare & Bounou (Lowel-Gueou) 08 Bara (Lowel-Gueou) 09 Borko (Bondum) 10 Tintam & Samari (Bondum) 11 Saoura Koum (plateau central) 12 Sangha 13 Pegue Toulou 14 Yougo Dogorou 15 The plain of Seno-Gondo 18 Architecture and traditional religion 20 Ginna (associated with the Wagem cult) 20 House of the Hogon (associated with the Lebe cult) 24 House of the Hogon of Arou 25 Binu shrine 26 Togu Na 29 Menstrual hut 31 Smithy 32 Altars 34 Mosque 35 The society of the masks 40 Funerary rites 40 Burial 40 Funeral 41 Funeral of the Hogon in Sangha - 1985 44 Masks 46 Mask Satimbe 47 Great Mask 48 Mask Sirige 50 Mask Kanaga 51 Various masks 52 Bibliography 57 www.dogon-lobi.ch is a travel journal. Photos presented were taken during some twenty trips spread over as many years. All these journeys were made on foot in the company of my friends Ana and Serou Dolo, sons of Diangouno Dolo, the late chief of Sangha. Today Ana is the owner of Hôtel Campement Gir-Yam in Sangha and Serou specializes in the building of wells and other water retention structures. Apart from some personal observations, the text that follows is based on the numerous ethnographic studies that have been conducted in Dogon country. It is an attempt to put a selection of photos in its cultural and historical context. -

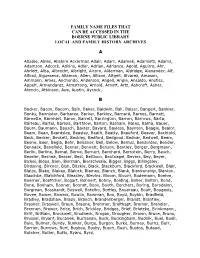

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

Obituaries Buffalo News 2010 by Name

Obituaries as found in the Buffalo News: 2010 Date of Place of Date, Page of Last Name/Maiden First Name M.I. Age Death Death/Birth/Residence Date, Page detailed obit Abbarno Vincent "Lolly" A. 9/26/2010 Kenmore, NY 9-30-2010: C4 Abbatte/Saunders Murielle A. 87 1/11/2010 1-13-2010: B4 Abbo Joseph D. 57 5/31/2010 Lewiston, NY 6-3-2010: B4 Brooksville, FL; formerly of Abbott Casimer "Casey" 12/19/22009 Cheektowaga, NY 4-18-2010: C6 Abbott Phillip C. 3/31/2010 4-3-2010: B4 Abbott Stephen E. 7/6/2010 7-8-2010: B4 Abbott/Pfoetsch Barbara J. 4/20/2010 5-2-2010: B4 Abeles Esther 95 1/31/2010 2-4-2010: C4 Abelson Gerald A. 82 2/1/2010 Buffalo, NY 2-3-2010: B4 Abraham Frank J. 94 3/21/2010 3-23-2010: B4 Abrahams/Gichtin Sonia 2/10/2010 died in California 2-14-2010: C4 Abramo Rafeala 93 12/16/2010 12-19-2010: C4 Abrams Charlotte 4/6/2010 4-8-2010: B4 Abrams S. "Michelle" M. 37 5/21/2010 Salamanca, NY 5-23-2010: B4 Abrams Walter I. 5/15/2010 Basom, NY 5-19-2010: B4 Abrosette/Aksterowicz Sister Mary 6/18/2010 6-19-2010: C4 Refer to BEN 2-21-2010: B6/7/8 for more possible Abshagen Charles, Jr. L. 73 2/19/2010 North Tonawanda, NY 2-22-2010: B8 information Acevedo Miguel A. 10/6/2010 Buffalo, NY 10-27-2010: B4 Achkar John E.