The Assignment of Cases to Judges Petra Butler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dinner Speech at the Conclusion of The

1085 DINNER SPEECH George Barton QC* This conference, now ending, has provided a special opportunity for those who have long admired Sir Ivor Richardson to celebrate his outstanding contribution to New Zealand, over many decades. All of those who have taken an active part in the Conference will have been honoured to co-operate in such wonderful festschrift. It has been like basking in reflected glory! On occasions like this, it has become almost traditional practice to recapitulate the biographical data of the guest of honour. The temptation to follow the standard practice should be resisted. Sir Ivor needs no reminding that he was born in Ashburton, was a pupil at Timaru Boys' High School, graduated in 1953 with an LLB degree from Canterbury University College of the University of New Zealand - and so on! Indeed, being constantly reminded of the basic facts in dinner-speech after dinner-speech, Sir Ivor might well be justified in drawing the inference that doubts are held about his ability to recall the most elementary facts about his own life. It is sometimes said that a mandatory age of retirement is explained as a kind of statutory presumption of senility. There is no room for such a rationalisation in Sir Ivor's case. But it must be acknowledged that mandatory retirement does avoid the kind of problems that seem to have arisen in the past when some Judges were able to remain on the Bench until their 80s, or even their 90s. One remarkable example was Salathiel Lovell, who was on the verge of 90 years of age when, in 1708, he was appointed a Baron of the Court of Exchequer in England. -

The Effectiveness of Tax Reviews in New Zealand: an Evaluation and Proposal for Improvement

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF TAX REVIEWS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EVALUATION AND PROPOSAL FOR IMPROVEMENT The Centre for Commercial and Corporate Law Inc 2020 i The Effectiveness of Tax Reviews in New Zealand: An Evaluation and Proposal for Improvement Published in Christchurch by The Centre for Commercial & Corporate Law Inc School of Law, University of Canterbury Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-473-52769-3 This publication is copyright. Other than for the purposes of and on the conditions prescribed by the Copyright Act no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means whether electronic, mechanical, microcopying, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner(s). The publisher, authors and editors expressly disclaim any and all liability to any person whether a purchaser of this publication or not in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted in reliance in whole or part. Published by the University of Canterbury ii Foreword FOREWORD This book proposes the establishment of a New Zealand Taxation Review Commission (NZTRC). It develops its argument for this in two ways. First, there is a survey of ad hoc tax reviews between 1922 and 2019. This survey ends with an analysis of the learnings that can be drawn from these reviews and draws together some thoughts on the characteristics of ‘best practice’ for review committees. Secondly, lessons are sought from a selection of permanent bodies that consider aspects of tax policy in a number of other countries. -

V.Alum 2012Pdf3mb

FACULTYFACULTY OFOF LAWLAW A YEARYEAR ININ REVIEWREVIEW 20122012 Welcome to another edition of V.Alum ACH YEAR FOR THE PAST FIVE YEARS it has been my privilege to E introduce you to our year’s work and the many achievements of our staff and students. I am always compelled to state how proud I am of those achievements and you, as readers, are within your rights to think ‘He would say that, wouldn’t he?’ (as Mandy Rice Davies said of a witness to the judge of her trial). This year is a little different. The work and talent of this Faculty has been judged in the QS World University Rankings by Subject, a global ranking that compares universities across 29 individual disciplines. The ranking features over 600 universities from 27 countries in the world, using more than 50,000 responses from academics and employers, and is the largest survey of its kind to date. The Faculty of Law at Victoria ranked highest in law for a New Zealand university, in the top five of law faculties in Australasia and 23rd in the world. It is wonderfully satisfying to have all the hard work, persistence and sheer talent of my colleagues recognised. On a more domestic note, our students feel the same way. In a survey of “Student Experience” conducted by Victoria University, we scored 89% in terms of satisfaction with their experience of this Faculty. This result is also rewarding in a different way. Our students are our ambassadors and a reflection of our core values and abilities. James G. -

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence

Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence Editor Dr Richard A Benton Editor: Dr Richard Benton The Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence is published annually by the University of Waikato, Te Piringa – Faculty of Law. Subscription to the Yearbook costs NZ$40 (incl gst) per year in New Zealand and US$45 (including postage) overseas. Advertising space is available at a cost of NZ$200 for a full page and NZ$100 for a half page. Communications should be addressed to: The Editor Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence School of Law The University of Waikato Private Bag 3105 Hamilton 3240 New Zealand North American readers should obtain subscriptions directly from the North American agents: Gaunt Inc Gaunt Building 3011 Gulf Drive Holmes Beach, Florida 34217-2199 Telephone: 941-778-5211, Fax: 941-778-5252, Email: [email protected] This issue may be cited as (2010) Vol 13 Yearbook of New Zealand Jurisprudence. All rights reserved ©. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1994, no part may be reproduced by any process without permission of the publisher. ISSN No. 1174-4243 Yearbook of New ZealaNd JurisprudeNce Volume 13 2010 Contents foreword The Hon Sir Anand Satyanand i preface – of The Hon Justice Sir David Baragwanath v editor’s iNtroductioN ix Dr Alex Frame, Wayne Rumbles and Dr Richard Benton 1 Dr Alex Frame 20 Wayne Rumbles 29 Dr Richard A Benton 38 Professor John Farrar 51 Helen Aikman QC 66 certaiNtY Dr Tamasailau Suaalii-Sauni 70 Dr Claire Slatter 89 Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie 112 The Hon Justice Sir Edward Taihakurei Durie 152 Robert Joseph 160 a uNitarY state The Hon Justice Paul Heath 194 Dr Grant Young 213 The Hon Deputy Chief Judge Caren Fox 224 Dr Guy Powles 238 Notes oN coNtributors 254 foreword 1 University, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, I greet you in the Niuean, Tokelauan and Sign Language. -

Tribute to Rt Hon Sir Ivor Richardson, Pcnzm

1 TRIBUTE TO RT HON SIR IVOR RICHARDSON, PCNZM Hon Justice John McGrath* The following is a tribute to the late Sir Ivor Richardson. It was delivered by Justice John McGrath at a memorial service held at Old St Paul's in Wellington on 29 January 2015. I INTRODUCTION When the news came, over the Christmas–New Year holiday period, that Sir Ivor Richardson had died, there was an immediate sense of awareness that New Zealand had lost an extraordinary man. The Chief Justice of New Zealand paid tribute to his "unparalleled influence on New Zealand law as a judge, law teacher and adviser".1 The Attorney-General said that he could think of no one who had made a more substantive contribution to law and social policy than Sir Ivor, adding that his was "a career marked by excellence in everything he did".2 In private emails responding to the news, a former Secretary to the Treasury spoke of Sir Ivor's "easy manner and intelligence" and his "massive contribution to taxation policy and administration". The present Secretary for Justice recalled working with Sir Ivor when a young departmental lawyer on a project for televising courts and said how progressive he was, with a constantly open mind. All present will have knowledge of some of the circumstances and events in the life of Ivor Lloyd Morgan Richardson. My task today is to give each of you a fuller picture of who he was, what he did and the outstanding and lasting contributions he made to New Zealand. II EARLY DAYS Ivor Richardson was born in Ashburton in 1930. -

Dames in New Zealand: Gender, Representation And

Dames in New Zealand: Gender, Representation and the Royal Honours System, 1917-2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by Karen Fox University of Canterbury 2005 Contents Abstract List of Figures ii Abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One: 28 An elite male institution: reproducing British honours in New Zealand Chapter Two: 58 In her own right: feminism, ideas of femininity and titles for women Chapter Three: 89 The work of dames and knights: exceptional women and traditional images of the feminine Chapter Four: 119 The work of dames and knights: traditional patterns in honours and non traditional work for women Conclusion 148 Appendix One: 166 Honours awarded in New Zealand, 1917-2000 Appendix Two: 174 Database of titular honours, 1917-2000 Bibliography 210 19 MAY Z005 Abstract The New Zealand royal honours system, as a colonial reproduction of an elite British system with a white male norm, has been largely overlooked in all fields of scholarship. Yet, as a state expression of what is valued in society, honours provide a window into shifts in society. This study of dames and knights is undertaken in the context of the changes in the lives of New Zealand women in the twentieth century. Situated in a changing and shifting environment, the honours system has itself changed, influenced by the ebb and flow of the feminist movement, the decline of imperial and aristocratic forces, and New Zealand's evolving independence and identity. At the same time, the system has been in some respects static, slow to respond to charges of being an imperial anachronism, and, despite some change in what areas of service titles were granted for, remaining a gendered space focused on the traditionally male-dominated fields of politics, law and commerce. -

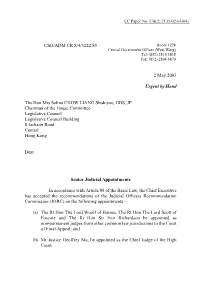

Cb(2)2135/02-03(04)

LC Paper No. CB(2) 2135/02-03(04) CSO/ADM CR 8/4/3222/85 Room 1228 Central Government Offices (West Wing) Tel: (852) 2810 3838 Fax: (852) 2804 6870 2 May 2003 Urgent by Hand The Hon Mrs Selina CHOW LIANG Shuk-yee, GBS, JP Chairman of the House Committee Legislative Council Legislative Council Building 8 Jackson Road Central Hong Kong Dear Senior Judicial Appointments In accordance with Article 88 of the Basic Law, the Chief Executive has accepted the recommendations of the Judicial Officers Recommendation Commission (JORC) on the following appointments - (a) The Rt Hon The Lord Woolf of Barnes, The Rt Hon The Lord Scott of Foscote and The Rt Hon Sir Ivor Richardson be appointed as non-permanent judges from other common law jurisdictions to the Court of Final Appeal; and (b) Mr Justice Geoffrey Ma, be appointed as the Chief Judge of the High Court. - 2 - The Chief Executive will announce his acceptance of the above recommendations of JORC this afternoon. An advance copy of the press statement is at Annex A for Members’ information. I should be grateful if Members would respect the confidentiality of the issue, pending the Chief Executive’s public announcement. Pursuant to Article 90 of the Basic Law, the Chief Executive shall obtain the endorsement of the Legislative Council of the appointments. Matters relating to the appointments are detailed in the papers at Annex B and Annex C. Representatives of the Administration and the Secretary of JORC would be happy to provide additional information and/or meet with Members to answer questions Members may have. -

Report on the Tax History Conference Held at Lucy Cavendish College

ATTA News February 2015 https://www.business.unsw.edu.au/about/schools/taxation-business-law/australasian-tax- teachers-association/newsletters Editor: Colin Fong, Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Sydney [email protected] ATTA website https://www.business.unsw.edu.au/about/schools/taxation-business- law/australasian-tax-teachers-association Contents 1 Presidential column 1 2 ATTA 2015 Conference wrap-up 2 3 ATTA Annual General Meeting minutes 3 4 ATTA medal presentation 6 5 Call for Articles: 2015 edition of JATTA 7 6 Impresssions of my first ATTA Conference 8 7 The Right Honourable Sir Ivor Richardson: Obituary 9 8 Arrivals, departures and honours 11 9 CCH transfer of academic textbooks to OUP 12 11 New Zealand developments 14 12 Recent Federal Court of Australia tax cases 14 13 The Right Honourable Sir Ivor Richardson: Scholarship available to download 16 14 Critical tax studies 17 15 Master of Laws in international tax law scholarship 17 16 Call for papers 17 17 Tax, accounting, economics and law related meetings 19 18 ATTA people in the media 22 19 Recent publications 23 20 Quotable quotes 27 1 Presidential column After such a great conference in Adelaide, if you are like me, the year is now in full swing with classes commencing and large numbers of students on campus. While the realities of teaching and administration take centre stage, I have many fond memories of the conference hosted by the University of Adelaide. On behalf of all ATTA members, a big Thank You to Domenic Carbone, John Tretola, Sylvia Villios and their team of volunteers for organising a great conference. -

Address at Memorial Sitting for the Rt Hon Sir Ivor Richardson, Pcnzm

15 ADDRESS AT MEMORIAL SITTING FOR THE RT HON SIR IVOR RICHARDSON, PCNZM Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias* The address was given at No 1 Court, Court of Appeal, Wellington, on Friday 1 May 2015. Te whare e tū nei, E ngā mate, haere atu rā. E ngā kanohi ora o rātou mā Nau mai, haere mai ki tēnei hui a Te Kooti Pira. It is my privilege to welcome you to this special sitting of Te Kooti Pira, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand. It is held to mark the service to law and to New Zealand of Ivor Lloyd Morgan Richardson – Judge of this Court for 25 years and its President for the last six years of his service as a Judge. I have greeted this courthouse, in which Sir Ivor sat from its opening in 1980. I have acknowledged those who have gone before, who are always with us on occasions such as this. I have greeted you, the living faces of those who have passed through this place, Te Kooti Pira, the Court of Appeal. On the bench with me are as many serving Judges as can fit and retired Judges of this Court and the High Court who sat with Sir Ivor and who have come, a number from a distance, because of their affection and deep respect for this leader of judges. Many others have written with their regrets at not being able to be here. I welcome in particular the family of Sir Ivor: Jane, Helen, Megan, and Sarah. We are grateful to you for allowing us this opportunity to pay tribute to the Judge. -

Faculty of Law

HANDBOOK 2017 This handbook is a guide for law students at the University of Otago. It describes the degrees offered, gives outline descriptions of the papers available in 2017, and notifies students of teaching arrangements and important dates. It also contains general information about the Faculty and the University that may be of use. Courses, examinations and other similar matters are governed by the regulations contained in the University Calendar, which should be consulted in cases of doubt. For ease of reference the regulations particularly concerning the Law Faculty are also reprinted in this handbook. If you need further help or advice, at any time during your studies, members of staff will always be available to assist you. Do not hesitate to approach us. Postal address: Street address: P O Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th Floors Telephone: 64 3 479 8857 Richardson Building Fax: 64 3 479 8855 85 Albany Street Email: [email protected] Dunedin, New Zealand Web Site: http://www.otago.ac.nz/law CONTENTS Introduction by Faculty Dean, Mark Henaghan .............................................................. 3 Historical note ....................................................................................................................... 6 Law Faculty Staff ................................................................................................................... 8 Law Faculty Staff Administrative Responsibilities .......................................................... 10 Law Staff Research Interests