Here He Handled the Counter-Terrorism and Regional Security Desks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Aviation Aircraft Propulsion: Power and Energy Requirements

UNCLASSIFIED General Aviation Aircraft Propulsion: Power and Energy Requirements • Tim Watkins • BEng MRAeS MSFTE • Instructor and Flight Test Engineer • QinetiQ – Empire Test Pilots’ School • Boscombe Down QINETIQ/EMEA/EO/CP191341 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Contents • Benefits of electrifying GA aircraft propulsion • A review of the underlying physics • GA Aircraft power requirements • A brief look at electrifying different GA aircraft types • Relationship between battery specific energy and range • Conclusions 2 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Benefits of electrifying GA aircraft propulsion • Environmental: – Greatly reduced aircraft emissions at the point of use – Reduced use of fossil fuels – Reduced noise • Cost: – Electric aircraft are forecast to be much cheaper to operate – Even with increased acquisition cost (due to batteries), whole-life cost will be reduced dramatically – Large reduction in light aircraft operating costs (e.g. for pilot training) – Potential to re-invigorate the GA sector • Opportunities: – Makes highly distributed propulsion possible – Makes hybrid propulsion possible – Key to new designs for emerging urban air mobility and eVTOL sectors 3 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Energy conversion efficiency Brushless electric motor and controller: • Conversion efficiency ~ 95% for motor, ~ 90% for controller • Variable pitch propeller efficiency -

Apis Contest Taurus(Electro)

Welcome NASA PAV Apis contest The CAFÉ Foundation’s With the addition of Inaugural NASA PAV Apis/Bee to the product Centennial Challenge line, Pipistrel is now concluded on August 11 in the most complex small Santa Rosa, California, and aircraft producer IN THE brought forth remarkable WORLD, the ONLY AIRCRAFT performances by several PRODUCER offering both Personal Air Vehicles (PAVs). single-seat and two- This great event was made seater side-by-side self- possible by support from launching gliders, two-seat NASA and Boeing Phantom motorgliders, UL two-seat INDEX Works. Winning teams go-the-distance aircraft, Electric Powered shared cash prizes from trikes and propellers. 1 Welcome Apis NASA totaling $250,000. We are excited about Taurus (Electro) Prizes were awarded for welcoming all existing and Electric Powered Taurus Shortest Runway, Lowest new Apis/Bee family owners Nasa PAV Contest Noise, Highest Top Speed, and we are confident to In 1995, Pipistrel d.o.o. Ajdovščina glide ratio of Best Handling Qualities, provide them with the best Our Dealers around the World were the first in the World to present at least 1:40; and Most Efficient, with possible service! a two-seat ultralight aircraft with a make gliding the grand Vantage Prize of From its beginnings, Apis/ 2 Project Hydrogenus wing-span of 15 meters, aimed also at cheap; provide $100,000 going to the best Bee was developed as a glider pilots. The aircraft was the Sinus, a fully equipped aircraft, including a Pipistrel Factory: combination of performance sister-ship to the Pipistrel’s still going strong in production. -

Narendra Modi and President Trump Are Not Just Similar but They Need Each Other at This Juncture

OPINION Narendra Modi and President Trump are not just similar but they need each other at this juncture The US President’s visit is aimed at boosting his own and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s political prole. The duo get on like a house on re and are mirror images of each other Engagement: Manish Madan 1.64 K Updated: 24 Feb 2020, 9:52 AM While President Donald Trump arrives in India after his acquittal on the charges of abuse of power and obstruction of Congress — having the dubious distinction of being only the third president in the US history to be impeached by the House — PM Modi is battling an uprising of millions of Indians demonstrating and protesting against a fundamentally discriminatory and religiously bigotedReach legislation, your goals Citizenship your Amendment way Act, 2019 (CAA) passed by his Hindu-Nationalist starts at government.$ 95 99 Shop now + FREE SHIPPING Versa 2 features may change, be discontinued, or require payment in future. It is also for the rst time that India’s most powerful Prime Minister has faced an unexpected real opposition, albeit outside the Parliament, from people of India including women protestors. It is therefore critical that despite the bromance and the hoopla of this historic visit, we must not lose sight of the current political environment that has beleaguered the two embattled leaders of the world’s largest and the oldest democracies. How To Easily Clean Earwax Earwax can cause hearing loss and memory loss. Try this simple x to remove earwax. ‘Namaste Trump’ or ‘Kem Chho Trump,’ brings a full circle to the ‘Howdy! Modi’ event that attracted nearly 50,000 Indian-Americans in Houston in September 2019, also attended by Trump. -

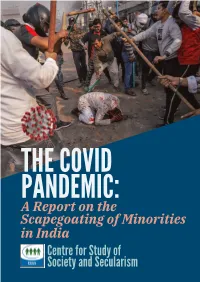

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

India-U.S. Relations

India-U.S. Relations July 19, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46845 SUMMARY R46845 India-U.S. Relations July 19, 2021 India is expected to become the world’s most populous country, home to about one of every six people. Many factors combine to infuse India’s government and people with “great power” K. Alan Kronstadt, aspirations: its rich civilization and history; expanding strategic horizons; energetic global and Coordinator international engagement; critical geography (with more than 9,000 miles of land borders, many Specialist in South Asian of them disputed) astride vital sea and energy lanes; major economy (at times the world’s fastest Affairs growing) with a rising middle class and an attendant boost in defense and power projection capabilities (replete with a nuclear weapons arsenal and triad of delivery systems); and vigorous Shayerah I. Akhtar science and technology sectors, among others. Specialist in International Trade and Finance In recognition of India’s increasingly central role and ability to influence world affairs—and with a widely held assumption that a stronger and more prosperous democratic India is good for the United States—the U.S. Congress and three successive U.S. Administrations have acted both to William A. Kandel broaden and deepen America’s engagement with New Delhi. Such engagement follows decades Analyst in Immigration of Cold War-era estrangement. Washington and New Delhi launched a “strategic partnership” in Policy 2005, along with a framework for long-term defense cooperation that now includes large-scale joint military exercises and significant defense trade. In concert with Japan and Australia, the Liana W. -

PM Modi's New Year's Address

Newsletter for the month of February 2020 India Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, the Visit of US President Donald Trump: home to Mahatma Gandhi during India’s freedom struggle. This was followed by the visit to Taj Mahal in Agra and bilateral meetings in New Delhi. Being leaders of sovereign and vibrant democracies recognizing the importance of freedom, equal treatment of all citizens, human rights and a commitment to rule of law, President Trump and PM Modi vowed to strengthen an India-US Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership. President Trump and PM Modi pledged to deepen bilateral US President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi defence and security cooperation, and agreed to promptly conclude ongoing trade At the invitation of India’s Prime Minister talks which could become phase one of a Shri Narendra Modi, US President Donald comprehensive bilateral trade agreement. Trump paid his first State Visit to India on February 24-25, 2020. He was Presentation of Union Budget 2020-21: accompanied by his wife First Lady Melania Trump, daughter Ivanka Trump and son-in-law Jared Kushner, as well as a high-level delegation. The visit began with the “Namaste Trump” event in Ahmedabad where President Trump inaugurated the world’s largest cricket stadium, the Sardar Patel Stadium and addressed a crowd of more than 100,000 Indians. President Trump and the First Finance Minister Smt. Nirmala Sitharaman Lady paid tribute to Mahatma Gandhi at presenting the Union Budget 2020-21 __________________________________________________________ Embassy of India, Niels Juels gate 30, 0244 Oslo Newsletter for February 2020 Tel. -

Comrade Krishna Chakraborty Is No More Veteran Member of SUCI(C) West Bengal Contd

ELECTRONIC VERSION PRINT COPY NOT AVAILABLE Volume 54 No. 19 Organ of the SOCIALIST UNITY CENTRE OF INDIA (COMMUNIST) Subscription Free May 15, 2021 Founder Editor-in-Chief : COMRADE SHIBDAS GHOSH Distributed via Internet Let the 63 billionaires who own Comrade Krishna Chakraborty Rs. 29 lakh crores donate is no more handsomely to Covid Relief Fund — demand people [Comrade Provash Ghosh, General Secretary, SUCI (Communist), urges people of India to sign the following memorandum to the Prime Minister asking for some urgent steps to combat the Covid menace.] To Shri Narendra Damodardas Modi The Hon’ble Prime Minister Government of India New Delhi Dear Sir, With grave concern, pain and shock we want to draw your attention to the grim fact that before the country could overcome the disastrous impact of the first corona wave, it has again been gripped by the second wave. First wave claimed thousands of lives and made millions of workers jobless, when your government miserably failed to give due attention to adopting necessary measures as you were engaged in ‘Namaste Trump festival’. Meanwhile, signal of second wave was given by the Western countries and you got some time to prepare for preventive measures. But again you did nothing as you became busy in construction of Ram Mandir, Central Vista and electoral scramble for power in some states by spending hundreds of crores of rupees. Now, the country is witnessing procession of human deaths and nobody knows where it will end. There is acute shortage of number of hospitals, beds, ICUs, oxygen, Comrade Krishna Chakraborty, former member of the Polit Bureau ventilators, medicines, doctors, nurses, medical persons etc. -

Research Article

s z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 12, Issue, 10, pp. 14421-14430, October, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24941/ijcr.39970.10.2020 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE ASSESSING INDO-US RELATIONS IN THE MODI’S ADMINISTRATION: EMERGENCE OF A NEW STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP *Mukti Sahu Lecturer in Political Science, Boudh Panchayat College, Boudh, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: This current paper is an attempt to explore & makes an assessment of the new dimensions of Indo-US Received 20th July, 2020 foreign policy and to advocate India’s influential role in international politics under the Prime Received in revised form Ministership of Narendra Modi. However, since 2014, after perceiving official designation, Modi 04th August, 2020 vehemently has sought to transform India’s queries to be an outstanding global leader in terms of Accepted 19th September, 2020 versatility and by profound active initiatives. As yet, the reform of Indian foreign policy ground-work Published online 30th October, 2020 after Nehru is extensively based on Modified doctrine to project and make India’s foreign policy as a superlative. The orientation of ‘political capital’ is as much as a new paradigm to bridge with other Key Words: foreign countries under the Narendra Modi. Similarly, the Indo-US proximity is much finest to Foreign Policy, Global Power, India- address and underling the various understanding in between their foreign relations. From day one of USA Relations, Narendra Modi, Modi’s administration, continual reflection during the Indo-US connectivity has deeply relied on Diplomacy, Strategy Partnership]. -

Impact of Non-Verbal Communication of Narendra Modi in International Communication (Special Reference Howdy Modi and Namaste Trump)

© 2020 JETIR April 2020, Volume 7, Issue 4 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Impact of Non-verbal communication of Narendra Modi in International Communication (Special reference Howdy Modi and Namaste Trump) Dr. Renu Singh Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Communication, Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya, Wardha, Maharashtra- 442001, Ram Sunder Kumar Research Scholar, Department of Mass Communication, Mahatma Gandhi Antarrashtriya Hindi Vishwavidyalaya. The international relations and foreign visits of the present prime minister has been the attraction of the Indian as well as the foreign media. The prime minister Narendra Modi has managed to be the focus of attraction in all his communication among the most powerful and famous political leaders of the world. The body language, handshakes, facial expression and eye contact of Narendra Modi with his foreign counterparts has added special meaning to his meetings. Moreover, the non-verbal behavior like handshakes and smiles between two political leaders also communicate their relations to their countrymen as well as to the rest of the world. India has always given special focus on its international relations. It has always tried to establish a friendly and equality-based relation with its international counterparts. But the non-verbal communication of the present prime minister Narendra Modi has a magical effect on the international platforms and communication. The present research proposes to study the non-verbal communication of the prime minister in his two famous international meetings with President Trump and particularly two events- Howdy Modi and Namaste Trump. Keywords- Non-verbal communication, Howdy Modi, Namaste Trump. The importance of the study remains in the fact that it tries to explore the image of an Indian Prime minister in the media and thus try to understand the feeling of pride among the millions of Indians when their leader is treated with love, respect and equality by the most powerful nation of the world. -

Indo-Us Strategic Relations: Modi's Road Map for Future

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 INDO-US STRATEGIC RELATIONS: MODI’S ROAD MAP FOR FUTURE PROSPECTS Roshan Ekka Ph.D Research Scholar, P.G Department of Political Science & Public Administration, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India Abstract creation of interaction between the states. Moreover, the Foreign policy is a dynamic concept. Thus the term establishment of the United Nations and the process of foreign policy or foreign relation is a broad concept on decolonization, liberated many states to sovereignty and which a country’s polices are determined and a nation’s further gave them the impetus of relationship between foreign policy is reflected by its realistic, ambitions, states. This led to the formation of “foreign policy” to state interest and domestic politics. So, foreign policy identify and define goals, strategies and objectives for always attempts to influence others in accordance with interaction with one state to another states.1 The term its own end. Foreign Policy is just like the wheels where Foreign Policy or Foreign Relation is broad concept on all the political systems of the world work together. A which a Nation’s policies are determined. Moreover, the nation’s foreign policy is concerned with the mind-set of country’s foreign policy is reflected by its realistic, a nation to the other nations. Foreign policy is the road ambitions, state interest and domestic politics. India as map where the governments of the sovereign states no doughty the creator of many international engage themselves in the world system for organizations such as Bretton Woods Institution, League accomplishing different aims and objectives. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Tanvi Madan EDUCATION the Lyndon B

CURRICULUM VITAE Tanvi Madan EDUCATION The Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin Ph.D., Public Policy (May 2012) Title: With an Eye to the East: The China Factor and the U.S.-India Relationship, 1949-1979 Yale University, New Haven, CT Master of Arts, International Relations (May 2003) Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University, New Delhi, India Bachelor of Arts with Honors, History (May 1999) SELECT EMPLOYMENT The Brookings Institution, Washington DC Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy and Director, The India Project (July 2019 – ) Fellow, Foreign Policy and Director, The India Project (June 2012 – June 2019) The Brookings Institution, Washington DC Research Analyst for Stephen P. Cohen and James B. Steinberg (July 2003 – July 2006) Embassy of India, Washington DC Intern, Political Wing (June 2002 – August 2002) Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut Member, WebTeam, Information Technology Services (September 2001 – May 2003) AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS Lyndon B. Johnson Library • Harry Middleton Fellowship in Presidential Studies (2009) The University of Texas at Austin • J.J. ‘Jake’ Pickle Scholarship (2009 – 2011) • Churchill Scholarship (2007 – 2010) • Donald D. Harrington Doctoral Fellowship (2006 – 2009) Yale University • University Fellowship (2002 – 03) • International Relations Summer Travel Grant (2002) Tanvi Madan Curriculum Vitae | INTERNAL ONLY Lady Shri Ram College • Faculty Prize for All-Round Contribution (1999) • Merit Scholarship (1996 – 1999) TEACHING EXPERIENCE The Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs, The University of Texas at Austin Instructor • Policy Orientation for International Students (Summer 2009) • Policy Orientation for International Students (Summer 2008) Teaching Assistant • Intelligence, Information and the Challenges of Globalization – James Steinberg (Fall 2008) • America and the World since 1947: Ideas and Practice – Elspeth Rostow and James Steinberg (Fall 2007) • The East Asian Century? Opportunities and Challenges for the Region and for the U.S. -

Celebrating Friendship US President Donald Trump’S Immensely Successful Maiden Visit to India Potpourri

SANITATION FOR ALL Success of the Swachh Bharat Mission LESSONS IN SUSTAINABILITY 34 01 2020 Volume | Issue | Ancient step wells and water conservation PICTURESQUE DELIGHTS The pristine lakes of Northeast India CELEBRATING FRIENDSHIP US President Donald Trump’s immensely successful maiden visit to India POTPOURRI Potpourri Events of the season MARCH, 2020 ATTUKAL PONGALA Each year, Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala, witnesses the arrival of millions of devotees who come to celebrate one of the oldest Pongala festivals in the state. Festivities last for 10 days at the 9 Attukal temple in Thiruvananthapuram. On the ninth day, millions of women gather to prepare a special rice meal to be offered to the temple deity. In 2009, a Guinness book record was set when 2.5 million women gathered at the temple for the festival. WHERE: Thiruvanathapuram, Kerala 1-7MARCH, 2020 INTERNATIONAL YOGA FESTIVAL Rishikesh, popularly known as the yoga capital of the world, 10 MARCH, 2020 hosts practitioners, conscious yogis and paradigm-shifting philosophers from over 80 countries for this event each year. The seven-day festival offers the ideal opportunity to learn and embrace every major style of yoga WHERE: Rishikesh, Uttarakhand HOLI One of the biggest highlights of the Indian festival calender, Holi celebrates the advent of spring. Over the years, this vibrant festival has been celebrated in many different hues across the country. Be it the playful celebrations in Mathura, the musical renditions in Varanasi or the royal processions across Rajasthan, Holi has correctly been called India’s very own cultural fiesta. WHERE: Across India INDIA PERSPECTIVES | 2 | 14-20 APRIL, 2020 APRIL, 2020 12 RONGALI BIHU EASTER The biggest agrarian festival in the state of Assam, Rongali Bihu is celebrated to commemorate the One of the largest celebrations amongst Christian advent of spring and the Assamese new year.