Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District ANDERSON 396 - XXX D PALESTINE PICNIC AND CAMPING PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $136,086.77 C 8/23/1976 3/1/1979 2 719 - XXX D COMMUNITY FOREST PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $275,500.00 C 8/23/1979 8/31/1985 2 ANDERSON County Total: $411,586.77 County Count: 2 ANDREWS 931 - XXX D ANDREWS MUNICIPAL POOL CITY OF ANDREWS $237,711.00 C 12/6/1984 12/1/1989 19 ANDREWS County Total: $237,711.00 County Count: 1 ANGELINA 19 - XXX C DIBOLL CITY PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $174,500.00 C 10/7/1967 10/1/1971 2 215 - XXX A COUSINS LAND PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $113,406.73 C 8/4/1972 6/1/1973 2 297 - XXX D LUFKIN PARKS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $49,945.00 C 11/29/1973 1/1/1977 2 512 - XXX D MORRIS FRANK PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $236,249.00 C 5/20/1977 1/1/1980 2 669 - XXX D OLD ORCHARD PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $235,066.00 C 12/5/1978 12/15/1983 2 770 - XXX D LUFKIN TENNIS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $51,211.42 C 6/30/1980 6/1/1985 2 879 - XXX D HUNTINGTON CITY PARK CITY OF HUNTINGTON $35,313.56 C 9/26/1983 9/1/1988 2 ANGELINA County Total: $895,691.71 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

GOOSE ISLAND STATE PARK STATE ISLAND GOOSE Concession Building

PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Born out of the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps put young men to work in the 1930s. The jobs involved building parks and conserving natural resources across the country. Many of our state parks here in Texas display the CCC’s handiwork. Texas now has 29 CCC state parks. Some, like Garner and Palo Duro Canyon, are well known to travelers across the state. So here’s a list of some CCC parks you may not have visited … yet. By Dale Blasingame � PHOTO BY EARL NOTTINGHAM / TPWD PHOTO © LAURENCEPHOTO PARENT ABILENE STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions CCC enrollees used native limestone and 150 Park Road 32 red sandstone to build many of the park’s Tuscola, TX 79562 features, including the arched concession building (with observation tower) and the Latitude: 32.240731 water tower. The CCC also constructed the Longitude: -99.879139 swimming pool, with pyramidal poolside pergolas. Online reservations (325) 572-3204 Entrance Fees Adult Day Use: $5 Daily Child 12 and Under: Free Visit park website PHOTO BY TPWD BY PHOTO BONHAM STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions The CCC touch can be seen everywhere – 1363 State Park 24 from the earthen dam used to form the Bonham, TX 75418 65-acre lake to the boathouse and park headquarters. Visit the CCC-constructed Latitude: 33.546727 picnic area first, which houses my favorite Longitude: -96.144758 footbridge in all of Texas. Online reservations (903) 583-5022 Entrance Fees Adult Day Use: $4 Daily Child 12 and Under: Free Visit park website PHOTO BY CHASE FOUNTAIN / TPWD CHASE BY PHOTO FOUNTAIN � MORE � DAVIS MOUNTAINS STATE PARK PARKS TO VIEW CCC WORK Map and directions Indian Lodge, the pueblo-style hotel in PO Box 1707 Davis Mountains State Park, reflects the Fort Davis, TX 79734 history and culture of the region. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

PWD MP P4506-001Fabilene.Ai

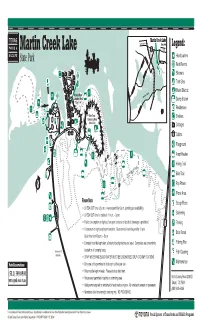

Martin Creek Lake To Henderson State Park Legend: 43 To Tatum Martin Creek Lake TEXAS FM 2144 Headquarters State Park CR 2183 Rest Rooms FM 2148 8 11 10 9 Power Showers 7 FM 2658 Plant 12 6 Tent Sites 13 5 14 4 FM 1251 Water/Electric 15 FM 2658 Broken Bowl k 16 Martin Cree Camping Area 55 54 56 53 Dump Station 17 52 Sites 1-34 57 18 34 51 3 33 32 31 66 67 Residences 19 58 65 68 69 50 22 30 70 FM 3231 20 2 23 64 24 Bee Tree 49 Shelters 59 Camping Area 71 1 25 21 29 Sites 35-81 72 48 60 63 2 47 Cottages 26 28 62 73 61 46 1 2 27 74 45 1 Cabins 81 75 80 35 76 44 36 37 79 Playground 38 78 77 39 43 42 Amphitheater 40 41 Hiking Trail Old Henderson Road Bike Trail Pay Phone Picnic Area Please Note: Group Picnic • CHECK OUT time is 2 p.m. or renew permit by 9 a.m. (pending site availability). • CHECK OUT time for cabins is 11 a.m. – 3 p.m. Swimming 43 • Public consumption or display of an open container of alcoholic beverage is prohibited. TEXAS Parking • A maximum of eight people per campsite. Guests must leave the park by 10 p.m. Boat Ramp Quiet time from 10 p.m. – 6 a.m. • Campsite must be kept clean; all trash picked up before you leave. Dumpsters are conveniently Fishing Pier Harmony Hill located on all camping loops. -

Inland Fisheries Annual Report 2013

INLAND FISHERIES ANNUAL REPORT 2013 IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF FISHING Carter Smith Gary Saul Executive Director Director, Inland Fisheries INLAND FISHERIES ANNUAL REPORT 2013 TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT Commissioners T. Dan Friedkin Chairman, Houston Ralph H. Duggins Vice-Chair, Fort Worth Antonio Falcon, M.D. Rio Grande City James H. Lee Houston Dan Allen Hughes, Jr. Beeville Bill Jones Austin Margaret Martin Boerne S. Reed Morian Houston Dick Scott Wimberley Lee M. Bass Chairman-Emeritus Ft. Worth TABLE OF CONTENTS INLAND FISHERIES OVERVIEW ............................................................. 1 Mission 1 Scope 1 Agency Goals 1 Division Goals 1 Staff 1 Facilities 2 Contact Information 2 Funding and Allocation 3 ADMINISTRATION .................................................................................... 4 HABITAT CONSERVATION ..................................................................... 5 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AND RESEARCH ..................................... 12 FISH HATCHERIES ................................................................................ 18 ANALYTICAL SERVICES ....................................................................... 19 INFORMATION AND REGULATIONS .................................................... 22 TEXAS FRESHWATER FISHERIES CENTER ....................................... 24 APPENDIX ............................................................................................... 26 Organization Charts 27 Surveys Conducted in Public Waters 35 Stocking Reports -

Download The

-Official- FACILITIES MAPS ACTIVITIES Get the Mobile App: texasstateparks.org/app T:10.75" T:8.375" Toyota Tundra Let your sense of adventure be your guide with the Toyota BUILT HERE. LIVES HERE. ASSEMBLED IN TEXAS WITH U.S. AND GLOBALLY SOURCED PARTS. Official Vehicle of Tundra — built to help you explore all that the great state the Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation of Texas has to offer. | toyota.com/trucks F:5.375" F:5.375" Approvals GSTP20041_TPW_State_Park_Guide_Trucks_CampOut_10-875x8-375. Internal Print None CD Saved at 3-4-2020 7:30 PM Studio Artist Rachel Mcentee InDesign 2020 15.0.2 AD Job info Specs Images & Inks Job GSTP200041 Live 10.375" x 8" Images Client Gulf States Toyota Trim 10.75" x 8.375" GSTP20041_TPW_State_Park_Guide_Ad_Trucks_CampOut_Spread_10-75x8-375_v4_4C.tif (CMYK; CW Description TPW State Park Guide "Camp Out" Bleed 11.25" x 8.875" 300 ppi; 100%), toyota_logo_vert_us_White_cmyk.eps (7.12%), TPWF Logo_2015_4C.EPS (10.23%), TPWF_WWNBT_Logo_and_Map_White_CMYK.eps (5.3%), GoTexan_Logo_KO.eps (13.94%), Built_Here_ Component Spread Print Ad Gutter 0.25" Lives_Here.eps (6.43%) Pub TPW State Park Guide Job Colors 4CP Inks AE Media Type Print Ad Production Notes Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date Due 3/5/2020 File Type Due PDFx1a PP Retouching N/A Add’l Info TM T:10.75" T:8.375" Toyota Tundra Let your sense of adventure be your guide with the Toyota BUILT HERE. LIVES HERE. ASSEMBLED IN TEXAS WITH U.S. AND GLOBALLY SOURCED PARTS. Official Vehicle of Tundra — built to help you explore all that the great state the Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation of Texas has to offer. -

Men of Affairs of Houston and Environs : a Newspaper Reference Work

^ 1Xctt)S|japer :ia;jg« '*ri'!iT Pi HMiMlhuCTII MEN OF AFFAIRS ;. AND REPRESEI^TaTIVE INSTITUTIONS OF HOUSTON AND ENVIRONS Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 witii funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/menofaffairsofhoOOhous ^ A Newspaper Reference Work mmm m TIHIE IHIOPSTOM FEESS CLUJE W. H. CoYLE & Company printers and stationers Houston. Texas f 39 H (*) ^ e 5 -^1 3 H fo ^ HE HOUSTON PRESS CLUB " herewith presents a book of photographs and hfe sketches of business and professional men of Houston and environs—men who are performing their share in the world's work. Our purpose, rather than to give any citizen or enterprise an undue amount of publicity, IS to provide for metropolitan newspaper libraries throughout the coun- try a work of reference on Houston citizens. All vital facts in the biographies have been furnished by the subjects themselves; so that this book is as nearly correct as anything of the sort ever published. May 1 St, 1913 (5) r A Newspaper R e f e e n c e Work HARRY T. WARNER PRESIDENT HOUSTON PRESS CLUB ARRY T. WARNER, first and incumbent president _n. of the Houston Press Club, managing editor of the Houston Post, was born at A'lontgomery, Alabama, and at an early age was brought by his parents to Texas; entered the newspaper business at 12 years of age at Austin, Texas, as a galley boy on the Austin States- rnan (1882); served his time as a printer; made a tour of the principal cities of Texas and of the East and then became con- nected with the editorial department of the Houston Post, with which paper he has remained in various managerial capacities for twent>' years. -

Diptera: Asilidae)

Zootaxa 2545: 1–22 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Nearctic species related to Diogmites angustipennis Loew (Diptera: Asilidae) JEFFREY K. BARNES University of Arkansas, Department of Entomology, 319 Agriculture Building, Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Diogmites bilobatus sp. nov. is described from museum specimens collected in the south central and southwestern United States and northern Mexico. Its close resemblance to the widespread D. angustipennis Loew is established. Diogmites grossus Bromley syn. nov., D. pulcher (Back) syn. nov., and D. symmachus Loew syn. nov. are synonymized with D. angustipennis, and lectotypes are designated for D. angustipennis and D. symmachus. Notes on morphological variation, habitat, prey, distribution, and phenology are provided for D. bilobatus sp. nov. and D. angustipennis. Key words: Brachycera, Dasypogoninae, Nearctic, new species, robber flies Introduction In the middle and western United States, some of the most common species of the robber fly genus Diogmites (Diptera: Asilidae: Dasypogoninae) can be recognized by the prominent, oblique, dark, lateral patches subtended by silver or golden pollen on abdominal tergites 2–5 (Fig. 1); the narrow and lightly infuscate wings; and usually a lack of distinct dark markings on the golden brown to dark brown scutum. When the dark abdominal patches are not connected across the surface of the tergites, the abdomen has a bright golden orange appearance. However, the patches in many specimens are connected across the tergites by diffuse brown to nearly black bands, giving the abdomen a dark disposition. -

Wilderness Camping Trips

P R O J E C T S U C C E S S 2019-2020 Impact Report Contents Introduction 2 Phases of Services 3 Wilderness Camping 7 Our Impact 10 Research Partnership 11 The Results of Our Work 12 Demographics 14 From Our Alumni - Testimonials 15 Thank You 16 Donor Partners 17 Our Beginning Every year 1.2 million students drop out of high school. In other words, every twenty-six seconds a student in America loses his or her path to a better future (Miller, 2015). By empowering students to stay in school and achieve in life, we are building a stronger America, where every person is capable of reaching his or her greatest potential. During the 2005 - 2006 school year CIS developed an initiative to bridge the high school to post- secondary education gap for CIS graduates called Project Success. For fourteen years, Project Success has served students who would otherwise have very limited knowledge of the college environment and the admissions process. Project Success strives to understand the first- generation college student, their barriers to success, the uncertainty they face and what is working in the field that propels them into marketable careers. Our Approach Through a dual approach Project Success is able to provide on-going, comprehensive campus-based one-on-one and group counseling services, which include high school, college and career counseling and an intensive summer bridge program – Life Bootcamp - for recent CIS graduates. CIS alumni programming begins at that point and includes mentoring, year round engagement, and wilderness experiences in state and national parks. -

Interpretive Guide |

INTERPRETIVE GUIDE LOCKHART STATE PARK Fun and relaxation await you! Hike one of the meandering WELCOME TO LOCKHART trails, fish in Clear Fork Creek, play a round of golf, or enjoy a night of peace and quiet at one of our campsites. STATE PARK! HERE, THE However you experience the park, please do so responsibly! CLEAR FORK CREEK AND ITS • Trash your trash. LUSH, SHADY FORESTS HAVE • Hike on designated trails and park in designated areas. • ATTRACTED PEOPLE FOR Respect wildlife by keeping your dog on a leash. • Ensure your own safety by not swimming in the creek. THOUSANDS OF YEARS. LARGE BLUFFS OFFER NEARBY ATTRACTIONS REMARKABLE VIEWS OF Palmetto State Park, Gonzales McKinney Falls State Park, Austin NATURAL AND HISTORIC Bastrop State Park, Bastrop BEAUTY, WHILE THE LOW- City of Lockart: the official BBQ capital of Texas! LANDS AND CREEK OFFER A Lockhart State Park NICE RESPITE FROM THE 2012 State Park Road Lockhart, Texas 78644 HOT SUMMER SUN. TEXAS (512) 398-3479 www.tpwd.texas.gov/lockhart NATURE AND CULTURE COME TOGETHER IN THIS LITTLE PIECE OF THE GREAT OUTDOORS. © 2021 TPWD. PWD BR P4505-0047J (7/21) TPWD receives funds from the USFWS. TPWD prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, disability, age, and gender, pursuant to state and federal law. To request an accommodation or obtain information in an alternative format, please contact TPWD on a Text Telephone (TTY) at (512) 389-8915 or by Relay Texas at 7-1-1 or (800) 735-2989 or by email at [email protected]. -

Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation James Cozine

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 31 | Issue 2 Article 10 10-1993 Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation James Cozine Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Cozine, James (1993) "Defining the Big Thicket: Prelude to Preservation," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 31: Iss. 2, Article 10. Available at: http://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol31/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 57 DEFINING THE BIG THICKET: PRELUDE TO PRESERVATION by James Cozine President Gerald Ford signed Public Law 93-439 on October 11, 1974, establishing an 84,550-acre Big Thicket National Preserve scattered over a seven-county area of Southeast Texas. The president's signature ended a forty-seven year dispute between timber firms and preservationists over the future use of that East Texas wilderness. I Part of the reason for the length of the dispute was the difficulty of defining the Big Thicket. What is the Big Thicket, and where is it located are questions which people have tried to answer for years. Indeed, without a consensus definition the timber firms, who owned much of the land slated for preservation, could argue that their land was not part of the Big Thicket and should not be included in any proposed preserve.