Money Laundering and Tax Evasion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tackling Tax Avoidance, Evasion and Other Forms of Non-Compliance

Tackling tax avoidance, evasion, and other forms of non- compliance March 2019 Tackling tax avoidance, evasion, and other forms of non-compliance Presented to Parliament pursuant to sections 92 and 93 of the Finance Act 2019 March 2019 © Crown copyright 2019 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-912809-45-5 PU2245 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter 1 HM Revenue and Customs’ strategic approach 4 Chapter 2 The government’s approach to addressing tax 11 avoidance, evasion and other forms of non-compliance Chapter 3 Investment in HM Revenue and Customs and a 20 commitment to further action Annex A List of measures to tackle tax avoidance, evasion and 22 non-compliance announced since 2010 Annex B Reports fulfilling the obligations of the Chancellor of 53 the Exchequer under sections 93 and 92 of Finance Act 2019 1 Introduction The vast majority of taxpayers, from individuals and the smallest businesses to the largest companies, already pay their fair share toward our vital public services. This government recognises its duty to that compliant majority to build a fair tax system, and through that system to make sure that those who try to cheat the Exchequer, through whatever means, are caught and forced to pay what they owe. -

Tanzania the Panama Papers in Africa

Tanzania The Panama Papers in Africa: Tax Avoidance, Money Laundering or Illicit Financial Flows? Olwethu Majola-Kinyunyu LLB, LLM PhD Candidate, Centre of Criminology, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa Email: [email protected] Abstract Early in 2016 the international community was shaken by the news of the biggest data leak in history. Political figures, prominent business people, sportstars and even criminals were the topic of discussion in news outlets across the globe. Following the release of the Panama Papers, many called for the leaders who were implicated to resign from their positions and for business executives to be investigated. There were reports of offshore accounts and companies operating in tax havens and accusations of money laundering, terrorism financing and tax avoidance. What do the Panama Papers mean for Africa? This paper assesses the effects of the Panama Papers on the African continent and evaluates whether the responses by African states are sufficient. What are the Panama Papers? tax haven jurisdictions in the facilitation of tax evasion, money laundering, organised crime, illicit The ?Panama Papers? is the colloquial term referring to the leak of client documents belonging to financial flows and other issues of grave concern to Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca. Details of the the international community. Panama documents were leaked by German newspaper, The Legality of Offshore Accounts and Companies in Süddeutsche Zeitung, in conjunction with the African Jurisdictions International Consortium of Investigative Journalists Holding ownership of a shell company or an offshore (ICIJ), consisting of over 100 media partners in 82 account, in most cases, is not unlawful. -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

Schwellenwert: Außenprüfung Bei Einkunftsmillionären Panama

KURZ INFORMIERT PStR ▶▶Finanzgericht Schleswig-Holstein Schwellenwert: Außenprüfung bei Einkunftsmillionären | Das FG Schleswig-Holstein (22.5.17, 2 V 22/17, Abruf-Nr. 195598) hat ent- schieden, dass Kapital einkünfte, für die eine Günstigerprüfung nach § 32d Abs. 6 EStG beantragt wurde, bei der Berechnung des Schwellenwerts von 500.000 EUR (§ 193 Abs. 1 AO i.V. mit § 147a AO) mitzählen. | Aufgrund der Günstigerprüfung werden die Kapitaleinkünfte nicht mehr der Günstigerprüfung: Abgeltungsteuer unterworfen, sondern als tarifbesteuerte Überschuss ein- Kapitaleinkünfte künfte gemäß § 2 Abs. 1 Nr. 5 EStG erfasst. Als solche sind sie beim Schwellen- werden der wert i.S. des § 193 Abs. 1 AO i.V. mit § 147a AO zu berücksichtigen. Dass zuvor tariflichen ESt Abgeltungsteuer einbehalten wurde, sei unerheblich. unterworfen Auch eine Saldierung mit negativen Einkünften aus anderen Jahren finde nicht statt. Auf den AEAO zu § 147a AO (BMF 31.1.14, BStBl I 14, 290), nach dem der Abgeltungsteuer unterfallende Einkünfte beim Schwellenwert nicht mit- zählen, konnte sich der Steuerpflichtige nicht berufen. Diese Regelung gilt nur für Fälle des § 32d Abs. 1 EStG, nicht aber für § 32d Abs. 6 EStG. Gegen den Beschluss wurde Beschwerde eingelegt (BFH VIII B 67/17). (DR) ▶▶Oberlandesgericht Stuttgart Panama Papers: Besitzer von Briefkastenfirmen kann identifizierende Medienberichte nicht verhindern | Das Phänomen der in Steuerparadiesen unterhaltenen Briefkastenfirmen stellt für die Allgemeinheit einen Missstand von erheblichem Gewicht dar, der nach höchstrichterlicher Rechtsprechung ein überragendes öffentliches Informationsinteresse begründet. | Dieses öffentliche Informationsinteresse rechtfertigt nach Ansicht des OLG Name der Person Stuttgart (8.2.17, 4 U 166/16, Abruf-Nr. 197543) sogar eine identifizierende darf in der Presse Zeitungs-Bericht erstattung über eine prominente Person, die derartige genannt werden Briefkastenfirmen im Zuge ihrer Agententätigkeit genutzt hat. -

Following the Money: Lessons from the Panama Papers Part 1

ARTICLE 3.4 - TRAUTMAN (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/2017 6:57 AM Following the Money: Lessons from the Panama Papers Part 1: Tip of the Iceberg Lawrence J. Trautman* ABSTRACT Widely known as the “Panama Papers,” the world’s largest whistleblower case to date consists of 11.5 million documents and involves a year-long effort by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists to expose a global pattern of crime and corruption where millions of documents capture heads of state, criminals, and celebrities using secret hideaways in tax havens. Involving the scrutiny of over 400 journalists worldwide, these documents reveal the offshore holdings of at least hundreds of politicians and public officials in over 200 countries. Since these disclosures became public, national security implications already include abrupt regime change and probable future political instability. It appears likely that important revelations obtained from these data will continue to be forthcoming for years to come. Presented here is Part 1 of what may ultimately constitute numerous- installment coverage of this important inquiry into the illicit wealth derived from bribery, corruption, and tax evasion. This article proceeds as follows. First, disclosures regarding the treasure trove of documents * BA, The American University; MBA, The George Washington University; JD, Oklahoma City Univ. School of Law. Mr. Trautman is Assistant Professor of Business Law and Ethics at Western Carolina University, and a past president of the New York and Metropolitan Washington/Baltimore Chapters of the National Association of Corporate Directors. He may be contacted at [email protected]. The author wishes to extend thanks to those at the Winter Conference of the Anti-Corruption Law Interest Group (ASIL) in Miami, January 13–14, 2017 who provided constructive comments to the manuscript, in particular: Eva Anderson; Bruce Bean; Ashleigh Buckett; Anita Cava; Shirleen Chin; Stuart H. -

Paradise Papers: a Global Investigation | Pulitzer Center 5/6/20, 11:36 AM

Paradise Papers: A Global Investigation | Pulitzer Center 5/6/20, 11:36 AM ACCESS OUR LATEST REPORTING AND RESOURCES ON COVID-19 → (https://pulitzercenter.org/covid-19) × PROJECT Paradise Papers The Paradise Papers is a global investigation that reveals the offshore activities of ICIJ's global investigation that reveals the some of the world’s most powerful people and companies. offshore activities of some of the world’s most powerful people and companies. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and more than 95 media AUTHOR partners explored 13.4 million leaked files from a combination of offshore law firms and company registries of some of the world’s most secretive countries. The files were obtained by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. ALVARO ORTIZ As a whole, the Paradise Papers expose offshore holdings of political leaders and their financiers as well as household-name companies that slash taxes and operate (https://pulitzercenter.org/people/alvaro- in secret. Financial deals of billionaires, celebrities and sports stars are also ortiz) revealed in the documents. Grantee The leak details the offshore activities of 13 advisers, donors and members of Álvaro Ortiz is the founder of Populate, a product design studio focused on civic engagement. Among President Donald J. Trump’s administration, including Commerce Secretary Wilbur other projects, Populate created the Panama Papers Ross’s interests in a shipping company that makes millions of dollars from an website and Offshore Leaks searchable database... energy firm whose owners include Russian President Vladimir Putin’s son-in-law and a sanctioned Russian tycoon. ROCCO FAZZARI President Donald Trump vowed to fight the power of global elites and told voters he would put “America First.” But surrounding Trump are a number of close (https://pulitzercenter.org/people/rocco- associates who have used offshore tax havens to conduct business. -

Panama Papers Law Firm Mossack Fonseca 'To Close'

Panama Papers Leak Panama Papers law firm Mossack Fonseca ‘to close’ Scandal over use of offshore financial centres by global wealthy hits business Cat Rutter Pooley and Barney Thompson in London YESTERDAY Mossack Fonseca, the law firm at the centre of the Panama Papers scandal, will close at the end of March, according to a statement from the firm obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. “The reputational deterioration, the media campaign, the financial siege and the irregular actions of some Panamanian authorities, have caused irreparable damage,” the statement said. As a result there would be a “total cessation of operations to the public at the end of this month after 40 years”. The ICIJ reported that Mossack Fonseca had told clients in November that it had had to “significantly reduce” its staff due to changes to the laws and an “adverse business environment”. The firm said it had previously had a presence in more than 40 countries, with “more than 600 collaborators around the world” before the data leak that exposed the widespread use of offshore financial centres by the global wealthy. By the time of its demise, it had fewer than 50 employees. The Panama Papers scandal, which erupted in April 2016, centred on the leak of 11.5m files from Mossack Fonseca, one of the largest offshore law firms, to the ICIJ and a range of news organisations. Among the stories were revelations about offshore accounts linked to the father of David Cameron, former UK prime minister; a close friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin; and Iceland’s Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, who later resigned as prime minister. -

The Panama Papers and Investigative Journalism in Africa Lessons Learned from and About the Data

3. The role of open data THE PANAMA PAPERS AND INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM IN AFRICA LESSONS LEARNED FROM AND ABOUT THE DATA LESSONS LEARNED PAPER Summary Governments are tasked to raise and spend tax revenues wisely to improve the lives of all citizens. However, all too often resources are allocated to the few and away from the many who are most in need. Such discrimination needs to be documented and made transparent. Opening up data can help to facilitate the process. Data can often tell us the basics: the who, what, where, when and why of financial transactions. And investigative reporters can use data to provide answers to these crucial questions, and to mobilise citizens and institutions to hold the offenders to account. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), together with the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 other media partners, spent a year sifting through 11.5 million leaked files from the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca to expose the reported offshore holdings of world leadersand details of hidden financial dealings. The leaked data was commonly referred to as the Panama Papers. The African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR), supported by funders such as the World Wide Web Foundation and Open Society Initiative of West Africa, coordinated and developed investigations in Africa. The Panama Papers project was the first time a major transnational investigation was coherently and collectively represented by journalists within the African countries being written about. This paper summarises the lessons learned from the African investigations of the Panama Papers, both in terms of what we learned about doing investigative data journalism in Africa and in terms of what those investigations revealed about the reported offshore holdings of the powerful and the deliberately complex governance structures allegedly set up to conceal the flow of money. -

The Panama Papers Prove: It Is Time for Action!

Herausgegeben von The Panama Papers prove: It is time for action! The Panama Papers constitute a massive leak of 11.5 million documents which are related to the law firm Mossack Fonseca based in Panama. Reports on the Panama Papers were first published on 3 April 2016; a large part of the data set has now been made publicly accessible. The volume of the Panama Papers exceeds the combined total of the Wikileaks Cablegate, Offshore Leaks, Lux Leaks, and Swiss Leaks, and has important implications for development cooperation. A holistic approach is needed to address the various dimensions of IFF. By Johannes Köckeis & Dr. Christiane Schuppert The Panama Papers have brought the issue of illicit financial linked with the revelations. In the case of Peru, both run-off flows (IFF) to the heart of public and political debate. The docu- presidential candidates were specified in the documents. ments reveal how the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca facilitated the creation of about 214.000 anonymous shelf com- The role of secrecy jurisdictions panies. 140 of these companies are connected to politicians or Financial centers that offer far reaching private protection rules public officials, such as Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson who was and allow the creation of shelf companies and similar legal enti- forced to resign as Prime Minister of Iceland due to the revela- ties are frequently referred to as secrecy jurisdiction. The benefi- tions of the Panama Papers. cial owner, that is the individual or entity that actually benefits from the funds, remains unknown. Many secrecy jurisdictions Within the context of the Panama Papers, several connections offer little or no tax liability to foreign individuals and businesses between partner countries of German development cooperation and are accordingly also referred to as tax havens. -

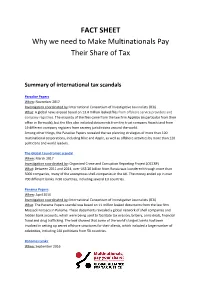

FACT SHEET Why We Need to Make Multinationals Pay Their Share Of

FACT SHEET Why we need to Make Multinationals Pay Their Share of Tax Summary of international tax scandals Paradise Papers When: November 2017 Investigation coordinated by: International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) What: A global news exposé based on 13.4 million leaked files from offshore serviCe providers and company registries. The majority of the files came from the law firm Appleby (in particular from their office in Bermuda), but the files also included documents from the trust company Asiaciti and from 19 different company registers from secrecy jurisdictions around the world. Among other things, the Paradise Papers revealed the tax planning strategies of more than 100 multinational Corporations, inCluding Nike and Apple, as well as offshore aCtivities by more than 120 politicians and world leaders. The Global Laundromat scandal When: March 2017 Investigation coordinated by: Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) What: Between 2011 and 2014, over US$ 20 billion from Russia was laundered through more than 5000 companies, many of the anonymous shell-companies in the UK. The money ended up in over 700 different banks in 96 countries, including several EU countries. Panama Papers: When: April 2016 Investigation coordinated by: International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) What: The Panama Papers scandal was based on 11 million leaked documents from the law firm MossaCk FonseCa in Panama. These doCuments revealed a global network of shell companies and hidden bank accounts, which were being used to facilitate tax evasion, bribery, arms deals, financial fraud and drug traffiCking. The leak showed that some of the world’s largest banks had been involved in setting up seCret offshore struCtures for their clients, which inCluded a large number of celebrities, including 140 politicians from 50 countries. -

Impact of the Panama Papers in Nigeria on Detection, Investigation

Impact of the Panama/Paradise Papers Leak in Developing Countries on Detection, Investigation and Recovery of the Illegally Gain Assets. By Rev. David Ugolor, Executive Director, Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice(ANEEJ) Phone: 234 70 35718577 Email: [email protected] UNCAC and London Anti-Corruption Summit,2016: Key Highlights • The United Nations Convention Against Corruption provides a global framework for tackling grand corruption • From London to Vienna: The Panama/Paradise Papers Leak have raised the number of issues • Civil Society and media active participation in the Asset Recovery debate through massive disclosure of grand corruption: The case of Malabo oil Scandal • The misuse of companies, legal entities and legal arrangement • Using Collective Action to disrupt illicit financial flows • Using FATF Recommendations on Transparency and Beneficial Ownership of Legal Persons and Arrangements • Making Beneficial Ownership accessible to civil society and the media • Establish Public Register/Egmont Group of FIUs Impact of Panama/Paradise Papers on Anti- Corruption Commitments • Increase media and civil society demands for transparency and accountability in the management public resources • Several developing Countries initiated investigation on these mentioned in the Panama Papers Leak • Local Media that participated in the Panama/Paradise Papers Leak through the International Consortium of Investigating Journalism(ICIJ) increased their visibility • Civil Society and Trade Union launched public protest calling on -

Lessons from the Panama Papers

The Chinese Journal of Global Governance 5 (2019) 176–196 brill.com/cjgg Do Corporate Governance Practices in One Jurisdiction Affect Another One? Lessons from the Panama Papers Bryane Michael University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong [email protected] Say Goo University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract To what extent do corporate governance practices in one jurisdiction affect another? In this paper, we look at the way that Hong Kong’s and the Mainland’s corporate gover- nance practices have co-evolved, along with offshore incorporations from both places. Drawing on empirical illustrations of the data using analytical techniques like differen- tial equations and Fourier Spectral Analysis, we find a strong relationship across time between changes in corporate governance practices in both jurisdictions as well as off- shore incorporations. Our data also support the idea of a theory-free equilibrium level of corporate governance (determined by market participants’ own behaviour rather than by a theory-laden econometric model). We show that lethargy likely explains the persistence of corporate governance practices in both places, with innovations in one place correlating with innovations in the other. Such work clearly implies that corpo- rate governance improvements in one place can help encourage such improvements in other markets which have not adopted laws aimed at improving corporate governance. Keywords Chinese corporate governance – Panama Papers – corporate governance spillovers – differential equations – Fourier spectral analysis © Bryane Michael and Say Goo, 2019 | doi:10.1163/23525207-12340043 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NCDownloaded 4.0 License.