ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: CULTURAL INTERVENTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

A General Survey of Religious Concepts and Art of North, East, South, and West Africa

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 369 692 SO 023 792 AUTHOR Stewart, Rohn TITLE A General Survey of Religious Concepts and Art of North, East, South, and West Africa. PUB DATE Jun 92 NOTE llp.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Art Education Association (Kansas City, KS, 1990). AVAILABLE FROMRohn Stewart, 3533 Pleasant Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN 55408 ($3). PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Art; *Art Education; *Cultural Background; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Interdisciplinary Approach; Multicultural Education; *Religion; *Religious Cultural Groups IDENTIFIERS *Africa ABSTRACT This paper, a summary of a multi-carousel slide presentation, reviews literature on the cultures, religions, and art of African people. Before focusing on West Africa, highlights of the lifestyles, religions, and icons of non-maskmaking cultures of North, West and South African people are presented. Clarification of West African religious concepts of God, spirits, and magic and an examination of the forms and functions of ceremonial headgear (masks, helmets, and headpieces) and religious statues (ancestral figures, reliquaries, shrine figures, spirit statues, and fetishes) are made. An explanation of subject matter, styles, design principles, aesthetic concepts and criteria for criticism are presented in cultural context. Numerous examples illustrated similarities and differences in the world views of West African people and European Americans. The paper -

American Society

AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared By Ner Le’Elef AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared by Ner LeElef Publication date 04 November 2007 Permission is granted to reproduce in part or in whole. Profits may not be gained from any such reproductions. This book is updated with each edition and is produced several times a year. Other Ner LeElef Booklets currently available: BOOK OF QUOTATIONS EVOLUTION HILCHOS MASHPIAH HOLOCAUST JEWISH MEDICAL ETHICS JEWISH RESOURCES LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT ORAL LAW PROOFS QUESTION & ANSWERS SCIENCE AND JUDAISM SOURCES SUFFERING THE CHOSEN PEOPLE THIS WORLD & THE NEXT WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book One) WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book Two) For information on how to order additional booklets, please contact: Ner Le’Elef P.O. Box 14503 Jewish quarter, Old City, Jerusalem, 91145 E-mail: [email protected] Fax #: 972-02-653-6229 Tel #: 972-02-651-0825 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: PRINCIPLES AND CORE VALUES 5 i- Introduction 6 ii- Underlying ethical principles 10 iii- Do not do what is hateful – The Harm Principle 12 iv- Basic human rights; democracy 14 v- Equality 16 vi- Absolute equality is discriminatory 18 vii- Rights and duties 20 viii- Tolerance – relative morality 22 ix- Freedom and immaturity 32 x- Capitalism – The Great American Dream 38 a- Globalization 40 b- The Great American Dream 40 xi- Protection, litigation and victimization 42 xii- Secular Humanism/reason/Western intellectuals 44 CHAPTER TWO: SOCIETY AND LIFESTYLE 54 i- Materialism 55 ii- Religion 63 a- How religious is America? 63 b- Separation of church and state: government -

In 1981, the Artist David Hammons and the Photographer Dawoud Bey Found Themselves at Richard Serra's T.W.U., a Hulking Corten

Lakin, Chadd. “When Dawoud Bey Met David Hammons.” The New York Times. May 2, 2019. Bliz-aard Ball Sale I” (1983), a street action or performance by David Hammons that was captured on camera by Dawoud Bey, shows the artist with his neatly arranged rows of snowballs for sale in the East Village. Credit Dawoud Bey, Stephen Daiter Gallery In 1981, the artist David Hammons and the photographer Dawoud Bey found themselves at Richard Serra’s T.W.U., a hulking Corten steel monolith installed just the year before in a pregentrified and sparsely populated TriBeCa. No one really knows the details of what happened next, or if there were even details to know aside from what Mr. Bey’s images show: Mr. Hammons, wearing Pumas and a dashiki, standing near the interior of the sculpture, its walls graffitied and pasted over with fliers, urinating on it. Another image shows Mr. Hammons presenting identification to a mostly bemused police officer. Mr. Bey’s images are funny and mysterious and offer proof of something that came to be known as “Pissed Off” and spoken about like a fable — not exactly photojournalism, but documentation of a certain Hammons mystique. It wasn’t Mr. Hammons’ only act at the site, either. Another Bey image shows a dozen pairs of sneakers Mr. Hammons lobbed over the Serra sculpture’s steel lip, turning it into something resolutely his own. Soon after he arrived in New York, from Los Angeles, in 1974, Mr. Hammons began his practice of creating work whose simplicity belied its conceptual weight: sculptures rendered from the flotsam of the black experience — barbershop clippings and chicken wing bones and bottle caps bent to resemble cowrie shells — dense with symbolism and the freight of history. -

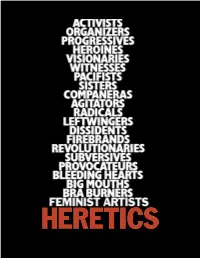

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

Feminist Art, the Women's Movement, and History

Working Women’s Menu, Women in Their Workplaces Conference, Los Angeles, CA. Pictured l to r: Anne Mavor, Jerri Allyn, Chutney Gunderson, Arlene Raven; photo credit: The Waitresses 70 THE WAITRESSES UNPEELED In the Name of Love: Feminist Art, the Women’s Movement and History By Michelle Moravec This linking of past and future, through the mediation of an artist/historian striving for change in the name of love, is one sort of “radical limit” for history. 1 The above quote comes from an exchange between the documentary videomaker, film producer, and professor Alexandra Juhasz and the critic Antoinette Burton. This incredibly poignant article, itself a collaboration in the form of a conversation about the idea of women’s collaborative art, neatly joins the strands I want to braid together in this piece about The Waitresses. Juhasz and Burton’s conversation is at once a meditation of the function of political art, the role of history in documenting, sustaining and perhaps transforming those movements, and the influence gender has on these constructions. Both women are acutely aware of the limitations of a socially engaged history, particularly one that seeks to create change both in the writing of history, but also in society itself. In the case of Juhasz’s work on communities around AIDS, the limitation she references in the above quote is that the movement cannot forestall the inevitable death of many of its members. In this piece, I want to explore the “radical limit” that exists within the historiography of the women’s movement, although in its case it is a moribund narrative that threatens to trap the women’s movement, fixed forever like an insect under amber. -

Season 8 Screening Guide-09.09.16

8 ART IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SCREENING GUIDE TO THE EIGHTH SEASON © ART21 2016. All Rights Reserved. art21.org | pbs.org/art21 GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE Through in-depth profiles and interviews, the four- This Screening Guide is designed to help you plan an part series reveals the inspiration, vision, and event using Season Eight of Art in the Twenty-First techniques behind the creative works of some of Century. For each of the four episodes in Season today’s most accomplished contemporary artists. Eight, this guide includes: ART21 travels across the country and abroad to film contemporary artists, from painters and ■ Episode Synopsis photographers to installation and video artists, in ■ Artist Biographies their own spaces and in their own words. The result ■ Screening Resources is a unique opportunity to experience first-hand the Ideas for Screening-Based Events complex artistic process—from inception to finished Screening-Based Activities product—behind today’s most thought-provoking art. Discussion Questions Links to Resources Online Season Eight marks a shift in the award-winning series. For the first time in the show’s history, the Educators’ Guide episodes are not organized around an artistic theme The 62-page color manual ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS includes infomation on artists, such as Fantasy or Fiction. Instead the 16 featured before-viewing, while-viewing, Public screenings of the Art in the Twenty-First artists are grouped according to the cities where and after-viewing discussion Century series illuminate the creative process of questions, as well as classroom they live and work, revealing unique and powerful activities and curriculum today’s visual artists in order to deepen audience’s relationships—artistic and otherwise—to place. -

Eleanor ANTIN B. 1935, the Bronx, NY Lives and Works in San Diego, CA, US

Eleanor ANTIN b. 1935, The Bronx, NY Lives and works in San Diego, CA, US EDUCATION 1958 BA Creative Writing and Art, City College of New York, NY 1956 Studied theatre at Tamara Dayarhanova School, New York, NY 1956 Graduate Studies in Philosophy, New School of Social Research, New York, NY SELECTED AWARDS 2011 Anonymous Was a Women Foundation, New York, NY 2009 Honorary Doctorate, School of the Arts Institute of Chicago, IL 2006 Honour Awards for Lifetime Achievements in the Visual Art, Women’s Caucus for Art, New York, NY 1996 UCSD Chancellor’s Associates Award for Excellence in Art, San Diego, CA 1984 VESTA Award for performance presented by the Women’s Building, Los Angeles, CA 1979 NEA Individual Artist Grant, Washington D.C. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Eleanor Antin: Romans & Kings, Richard Saltoun Gallery, London, UK 2016 CARVING: A Traditional Sculpture, (one work exhibition), Henry Moore Foundation, Leeds, UK I wish I had a paper doll I could call my own…, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY What time is it?, Diane Rosenstein Fine Arts, Los Angeles, CA 2014 Eleanor Antin: The Passengers, Diane Rosenstein Fine Arts, Los Angeles, CA Multiple Occupancy: Eleanor Antin’s “Selves”, ICA, Boston, MA. This exhibition travelled to: The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, NY 2009 Classical Frieze, Galerie Erna Hecey, Brussels, Belgium Classical Frieze, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA 2008 Eleanor Antin: Historical Takes, San Diego Art Museum, San Diego, CA Helen’s Odyssey, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY 2007 The Empire of Signs, Galerie Erna Hecey, Brussels, Belgium 2006 100 Boots, Erna Hecey Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2005 Roman Allegories, 2005 & 100 Boots, 1971 – 73, Marella Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy Roman Allegories, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, NY 2004 The Last Days of Pompeii, Mandeville Art Gallery, San Diego, CA 2002 The Last Days of Pompeii, Marella Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy. -

Newsletter 2009

NEWSLETTER 2009 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS 2 Letter from the Chair and President, Board of Trustees Skowhegan, an intensive 3 Letter from the Chair, Board of Governors nine-week summer 4 Trustee Spotlight: Ann Gund residency program for 7 Governor Spotlight: David Reed 11 Alumni Remember Skowhegan emerging visual artists, 14 Letters from the Executive Directors seeks each year to bring 16 Campus Connection 18 2009 Awards Dinner together a gifted and 20 2010 Faculty diverse group of individuals 26 Skowhegan Council & Alliance 28 Alumni News to create the most stimulating and rigorous environment possible for a concentrated period of artistic creation, interaction, and growth. FROM THE CHAIR & PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS ANN L. GUND Chair / GREGORY K. PALM President BYRON KIM (’86) We write to you following another wonderful Trustees’/ featuring a talk by the artist and in June for a visit leadership. We will miss her, but know she will bring Many years ago, the founders of the Skowhegan great food for thought as we think about the shape a Governors’ Weekend on Skowhegan’s Maine campus, to Skowhegan Trustee George Ahl’s eclectic and her wisdom and experience to bear in the New York School of Painting & Sculpture formed two distinct new media lab should take. where we always welcome the opportunity to see beautiful collection which includes several Skowhegan Arts Program of Ohio Wesleyan University, where governing bodies that have worked strongly together to As with our participants, we are committed to diversity the School’s program in action and to meet the artists.