Historic Furnishings Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Album of the Week: Descendents’ Hypercaffium

Album Of The Week: Descendents’ Hypercaffium Spazzinate In this crazy year we need punk rock more than ever. We need to listen to some amplified, angst-filled, guitar-driven music that ignites the rambunctiousness in all of us. Seems like the perfect time for the Descendents to put out their first album in 12 years, right? The punk legends from Manhattan Beach, California, have their seventh album, Hypercaffium Spazzinate, out and the fearsome foursome have gone back to what they do best. That’s unleashing feverish riffs, pristine drumming and lyrics that come straight from the heart. The title is an ode to frontman Milo Aukerman’s former career as a research biochemist while the album itself harks back to the Descendents’ earlier material in tone and style. When the band’s previous album Cool To Be You came out in 2004, polished pop punk was all over the place. Being a band that are considered to be pioneers of pop punk (which I find to be weird), the Descendents went with the times with Cool To Be You and put out a clean sounding album. Hypercaffium Spazzinate brings back the band’s edge that they had in the ’80s. The album’s production quality has a little bit of grit and that’s what a punk band should sound like. Pop punk is a bit of an oxymoron in my opinion. Punk started out as a genre that counteracted what pop music was in the ’70s and then punk bands started bringing melody. That’s what makes it pop? Maybe that’s why we have crappy bands like All Time Low and The Maine corrupting the youth, though that’s not the Descendents’ fault. -

Of Oatmeal, Bears, and Npes: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance Evan Mcalpine

Intellectual Property Brief Volume 4 | Issue 3 Article 2 7-10-2013 Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance Evan McAlpine Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation McAlpine, Evan. "Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance." Intellectual Property Brief 4, no. 3 (2013): 19-35. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intellectual Property Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance This article is available in Intellectual Property Brief: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/ipbrief/vol4/iss3/2 Of Oatmeal, Bears, and NPEs: Ensuring Fair, Effective, and Affordable Copyright Enforcement Through Copyright Insurance by Evan McAlpine1 1ABSTRACT link-backs or attribution. Accordingly, he requested the site’s administrator remove the infringing copies via a Increasing copyright infringement and DMCA takedown notice.6 high litigation costs have left many independent After fruitlessly sending -

Descendents All Mp3, Flac, Wma

Descendents All mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: All Country: US Released: 1987 Style: Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1791 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1728 mb WMA version RAR size: 1631 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 365 Other Formats: WMA MP3 ASF MMF DTS MIDI AHX Tracklist Hide Credits All 1 0:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson*, McCuistion* Coolidge 2 2:47 Lyrics By, Music By – Alvarez* No, All! 3 0:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson*, McCuistion* Van 4 3:01 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Alvarez*, Egerton* Cameage 5 3:05 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson* Impressions 6 3:08 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Iceman 7 3:14 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Jealous Of The World 8 4:04 Lyrics By, Music By – Aukerman* Clean Sheets 9 3:15 Lyrics By, Music By – Stevenson* Pep Talk 10 3:06 Lyrics By – Stevenson*, Aukerman*Music By – Aukerman* All-O-Gistics 11 3:04 Lyrics By – Stevenson*, McCuistion*Music By – Egerton* Schizophrenia 12 6:50 Lyrics By – Aukerman*Music By – Egerton* Uranus 13 2:15 Written-By – Descendents Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – SST Records Manufactured By – Laservideo Inc. – CI08141 Recorded At – Radio Tokyo Copyright (c) – Alltudemic Music Credits Bass, Artwork [Drawings] – Karl Alvarez Drums, Producer – Bill Stevenson Engineer – Richard Andrews Guitar – Stephen Egerton Management, Other [Booking] – Matt Rector Vocals – Milo Aukerman Vocals [Gator] – Dez* Notes Similar to Descendents - All except the disc is silver with blue lettering Recorded January 1987 at Radio Tokyo ℗ 1987 SST Records © 1987 Alltudemic Music (BMI) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 18861-0112-2 6 Matrix / Runout: MANUFACTURED IN U.S.A. -

The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau's Political Thought

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Politics School of Arts and Sciences of the Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Joshua James Bowman Washington, D.C. 2016 Arcadian Exile: The Imaginative Tension in Henry David Thoreau’s Political Thought Joshua James Bowman, Ph.D. Director: Claes G. Ryn, Ph.D. Henry David Thoreau‘s writings have achieved a unique status in the history of American literature. His ideas influenced the likes of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and play a significant role in American environmentalism. Despite this influence his larger political vision is often used for purposes he knew nothing about or could not have anticipated. The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze Thoreau’s work and legacy by elucidating a key tension within Thoreau's imagination. Instead of placing Thoreau in a pre-conceived category or worldview, the focus on imagination allows a more incisive reflection on moral and spiritual questions and makes possible a deeper investigation of Thoreau’s sense of reality. Drawing primarily on the work of Claes Ryn, imagination is here conceived as a form of consciousness that is creative and constitutive of our most basic sense of reality. The imagination both shapes and is shaped by will/desire and is capable of a broad and qualitatively diverse range of intuition which varies depending on one’s orientation of will. -

George P. Merrill Collection, Circa 1800-1930 and Undated

George P. Merrill Collection, circa 1800-1930 and undated Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: PHOTOGRAPHS, CORRESPONDENCE AND RELATED MATERIAL CONCERNING INDIVIDUAL GEOLOGISTS AND SCIENTISTS, CIRCA 1800-1920................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: PHOTOGRAPHS OF GROUPS OF GEOLOGISTS, SCIENTISTS AND SMITHSONIAN STAFF, CIRCA 1860-1930........................................................... 30 Series 3: PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE TERRITORIES (HAYDEN SURVEYS), CIRCA 1871-1877.............................................................................................................. -

THE QUINCENTENARY of COLUMBUS's ARRIVAL Editor's Note

HumanitiesNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES • VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 5 • SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 1991 THE QUINCENTENARY OF COLUMBUS'S ARRIVAL Editor's Note The Columbian Quincentenary As happens with important anniversaries, the Columbian Quincentenary is bringing forth a number of historical reappraisals. With that in mind, in this issue of Humanities we look at the quincentenary from a number of perspectives. Even the particular word chosen to describe what went on, says historian James Axtell, carries a particular weight and colora tion, whether that word be colonization or imperialism or settlement or emigration or THE QUINCENTENARY OF COLUMBUS'S ARRIVAL invasion. In attempting to reframe the moral imperatives of 1492 at a distance of five centuries, Axtell cautions: King Ferdinand points to Columbus landing "The parties of the past deserve equal treatment from historians___As judge, in the New World. Woodcut from Guiliano jury, prosecutor, and counsel for the defense of people who can no longer testify Dati's La Lettera Dellisole, 1493. (Library on their own behalf, the historian cannot be any less than impartial in his or of Congress) her judicial review of the past." W. Richard West, Jr., the director of the new National Museum of the American Humanities Indian and himself a Cheyenne, says something succinct and similar: "We have A bimonthly review published by the to be careful that we do not try to remake history into something that it was not." National Endowment for the Humanities One current NEH-supported exhibition called "The Age of the Marvelous" Chairman: Lynne V. Cheney covers the period following Columbus's journey. -

Sierra Club Members Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4j49n7st No online items Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Processed by Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant; machine-readable finding aid created by Brooke Dykman Dockter The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History --History, CaliforniaGeographical (By Place) --CaliforniaSocial Sciences --Urban Planning and EnvironmentBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --ForestryBiological and Medical Sciences --Agriculture --Wildlife ManagementSocial Sciences --Sports and Recreation Guide to the Sierra Club Members BANC MSS 71/295 c 1 Papers Guide to the Sierra Club Members Papers Collection number: BANC MSS 71/295 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Contact Information: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Processed by: Lauren Lassleben, Project Archivist Xiuzhi Zhou, Project Assistant Date Completed: 1992 Encoded by: Brooke Dykman Dockter © 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Sierra Club Members Papers Collection Number: BANC MSS 71/295 c Creator: Sierra Club Extent: Number of containers: 279 cartons, 4 boxes, 3 oversize folders, 8 volumesLinear feet: ca. 354 Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Physical Location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. -

Yosemite: Warming Takes a Toll

Bay Area Style Tuolumne County Gives Celebrating Wealthy renowned A guide to donors’ S.F. retailer autumn’s legacies Wilkes best live on Bashford’s hiking, through Island Style ever-so- climbing their good Unforgettable Hawaiian adventures. K1 stylish and works. N1 career. J1 biking. M1 SFChronicle.com | Sunday, October 18,2015 | Printed on recycled paper | $3.00 xxxxx• Airbnb measure divides neighbors Prop. F’s backers, opponents split come in the middle of the night, CAMPAIGN 2015 source of his income in addition bumping their luggage down to work as a real estate agent over impact on tight housing market the alley. This is not an occa- and renewable-energy consul- sional use when a kid goes to ing and liability issues. tant, Li said. college or someone is away for a But Li, 38, said he urges “I depend on Airbnb to make By Carolyn Said Phil Li, who rents out three week. Along with all the house guests to be respectful, while sure I can meet each month’s suites to travelers via Airbnb. cleaners, it’s an array of com- two other neighbors said that expenses,” he said. “I screen A narrow alley separates “He’s running a hotel next mercial traffic in a residential they are not affected. Vacation guests carefully and educate Libby Noronha’sWest Portal door,” said Noronha, 67,a re- neighborhood,” she said of the rentals helped him after he lost them to come and go quietly.” house from that of her neighbor tired federal employee. “People noise, smoking, garbage, park- his job and remain a major Prop. -

Punk Is Dead” Catalog Includes, the SST Records the Inventory Representing the “Punk Is Collection, C

2016 PUNK IS DEAD Lux Mentis, Booksellers Lux Mentis Booksellers specializes in fine press, artist books, first editions, Punk rock evolved over several and esoterica with a particular emphasis generations and manifestations of youth on challenging and unusual materials. culture beginning in the 1970s. Even after 40 years, punk subculture still We actively collaborate with archives demonstrates the capability to influence and special collections libraries to meet successive contemporary elements of the research and collecting needs of art, music, and fashion regardless of its public learning institutions, private, original intention to lambast conformity. independent libraries and collections with primary sources. Selected inventory in the “Punk is Dead” catalog includes, the SST Records The inventory representing the “Punk is Collection, c. 1979-1996; original Dead” collection is a retrospective artwork from famed punk artist, selection of critical primary source Raymond Pettibon; correspondence materials documenting the punk rock from Gordon Gano, original member of movement of the 1970s-1990s. The the Violent Femmes; and several unique collection illustrates the profound fanzine and alternative publications. subculture of punk from an artistic and politically fueled era from Los Angeles, Lux Mentis regularly features and New York, and London. showcases punk culture related materials at major ABAA book fairs and Please contact us for an appointment or continues to cultivate the acquisition of with questions regarding the inventory. subculture materials for research and collection development purposes. 110 Marginal Way #777 Portland, ME 04101 Member: ILAB/ABAA T. 207.329.1469 Email: [email protected] Front cover image: From the SST [email protected] Records Collection, detail of “Outcry” Web: http://www.luxmentis.com magazine Blog: http://www.asideofbooks.com Cataloged created by Kim Schwenk and edited by Ian Kahn 2 Ginn, Greg, Pettibon, Raymond, et al. -

Dowthwaite, Liz (2018) Crowdfunding Webcomics

CROWDFUNDING WEBCOMICS: THE ROLE OF INCENTIVES AND RECIPROCITY IN MONETISING FREE CONTENT Liz Dowthwaite Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 Liz Dowthwaite Crowdfunding Webcomics: The Role of Incentives and Reciprocity in Monetising Free Content Thesis submitted to the School of Engineering, University of Nottingham, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. © September 2017 Supervisors: Robert J Houghton Alexa Spence Richard Mortier i To my parents, and James. ii Doug Savage, 2007 http://www.savagechickens.com/2007/05/morgan-freeman.html “They’re not paying for the content. They’re paying for the people.” Jack Conte, founder of Patreon “We ascribe to the idealistic notion that audiences don’t pay for things because they’re forced to, but because they care about the stuff that they love and want it to continue to grow.” Hank Green, founder of Subbable iii CROWDFUNDING WEBCOMICS – LIZ DOWTHWAITE – AUGUST 2017 ABSTRACT The recent phenomenon of internet-based crowdfunding has enabled the creators of new products and media to share and finance their work via networks of fans and similarly-minded people instead of having to rely on established corporate intermediaries and traditional business models. This thesis examines how the creators of free content, specifically webcomics, are able to monetise their work and find financial success through crowdfunding and what factors, social and psychological, support this process. Consistent with crowdfunding being both a large-scale social process yet based on the interactions of individuals (albeit en mass), this topic was explored at both micro- and macro-level combining methods from individual interviews through to mass scraping of data and large-scale questionnaires. -

A New Storytelling Era: Digital Work and Professional Identity in the North American Comic Book Industry

A New Storytelling Era: Digital Work and Professional Identity in the North American Comic Book Industry By Troy Mayes Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Media, The University of Adelaide January 2016 Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................. vii Statement ............................................................................................ ix Acknowledgements ............................................................................. x List of Figures ..................................................................................... xi Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background and Context .......................................................... 2 1.3 Theoretical and Analytic Framework ..................................... 13 1.4 Research Questions and Focus ............................................. 15 1.5 Overview of the Methodology ................................................. 17 1.6 Significance .............................................................................. 18 1.7 Conclusion and Thesis Outline .............................................. 20 Chapter 2 Theoretical Framework and Methodology ..................... 21 2.1 Introduction .............................................................................. 21 -

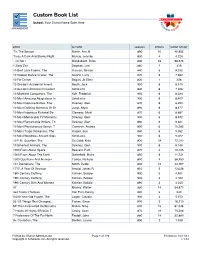

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R.