Family Law 240-001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Divorce Act Changes Explained

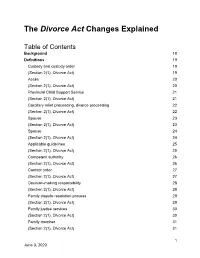

The Divorce Act Changes Explained Table of Contents Background 18 Definitions 19 Custody and custody order 19 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 19 Accès 20 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 20 Provincial Child Support Service 21 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 21 Corollary relief proceeding, divorce proceeding 22 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 22 Spouse 23 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 23 Spouse 24 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 24 Applicable guidelines 25 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 25 Competent authority 26 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 26 Contact order 27 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 27 Decision-making responsibility 28 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 28 Family dispute resolution process 29 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 29 Family justice services 30 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 30 Family member 31 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 31 1 June 3, 2020 Family violence 32 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 32 Legal adviser 35 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 35 Order assignee 36 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 36 Parenting order 37 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 37 Parenting time 38 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 38 Relocation 39 (Section 2(1), Divorce Act) 39 Jurisdiction 40 Two proceedings commenced on different days 40 (Sections 3(2), 4(2), 5(2) Divorce Act) 40 Two proceedings commenced on same day 43 (Sections 3(3), 4(3), 5(3) Divorce Act) 43 Transfer of proceeding if parenting order applied for 47 (Section 6(1) and (2) Divorce Act) 47 Jurisdiction – application for contact order 49 (Section 6.1(1), Divorce Act) 49 Jurisdiction — no pending variation proceeding 50 (Section 6.1(2), Divorce Act) -

OP 2 Processing Members of the Family Class

OP 2 Processing Members of the Family Class Updates to chapter ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1. What this chapter is about ...................................................................................................................... 6 2. Program objectives ................................................................................................................................. 6 3. The Act and Regulations ........................................................................................................................ 6 3.1. The forms required are shown in the following table. ..................................................................... 7 4. Instruments and delegations .................................................................................................................. 7 4.1. Delegated powers ........................................................................................................................... 7 4.2. Delegates/designated officers ......................................................................................................... 7 5. Departmental policy ................................................................................................................................ 8 5.1. Family class requirements .............................................................................................................. 8 5.2. Who must complete an IMM 0008? ............................................................................................... -

Chapter Five Spouses, Common-Law Partners and Conjugal Partners

Chapter Five Spouses, Common-Law Partners and Conjugal Partners Introduction The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (“IRPA”)1 and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (“IRP Regulations”)2 expanded the family class to include common-law partners and conjugal partners as well as spouses.3 In addition, common-law partners are family members of members of the family class.4 These changes, brought about by the implementation of the IRPA in 2002, are part of a legislative framework which sets out, for the first time, specific rules concerning the sponsorship of common-law partners and conjugal partners of the same or opposite sex as the sponsor.5 Modifications were also brought to the definition of “marriage.”6 The IRP Regulations now require that a foreign marriage be valid under Canadian law. Furthermore, contrary to the former Immigration Regulations, 1978, the IRPA and IRP Regulations do not define “spouse.” The discussion that follows addresses the definitions of “common-law partner,” “conjugal partner,” and “marriage.” It also deals with excluded and bad faith relationships which disqualify 1 S.C. 2001, c. 27, entered into force on June 28, 2002 as amended. 2 SOR/202-227, June 11, 2002 as amended. 3 S. 12(1) of the IRPA and s. 116 and s. 117(1)(a) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (“IRP Regulations”). “Common-law partner” is defined at s. 1(1) of the IRP Regulations as: “…in relation to a person, an individual who is cohabiting with the person in a conjugal relationship, having so cohabited for a period of at least one year.” “Conjugal partner” is defined at s. -

Private Law As Constitutional Context for Same-Sex Marriage

Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage Private Law as Constitutional Context for Same-sex Marriage ROBERT LECKEY * While scholars of gay and lesbian activism have long eyed developments in Canada, the leading Canadian judgment on same-sex marriage has recently been catapulted into the field of vision of comparative constitutionalists indifferent to gay rights and matrimonial matters more generally. In his irate dissent in the case striking down a state sodomy law as unconstitutional, Scalia J of the United States Supreme Court mentions Halpern v Canada (Attorney General).1 Admittedly, he casts it in an unfavourable light, presenting it as a caution against the recklessness of taking constitutional protection of homosexuals too far.2 Still, one senses from at least the American literature that there can be no higher honour for a provincial judgment from Canada — if only in the jurisdictional sense — than such lofty acknowledgement that it exists. It seems fair, then, to scrutinise academic responses to the case for broader insights. And it will instantly be recognised that the Canadian judgment emerged against a backdrop of rapid change in the legislative and judicial treatment of same-sex couples in most Western jurisdictions. Following such scrutiny, this paper detects a lesson for comparative constitutional law in the scholarly treatment of the recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada. Its case study reveals a worrisome inclination to regard constitutional law, especially the judicial interpretation of entrenched rights, as an enterprise autonomous from a jurisdiction’s private law. Due respect accorded to calls for comparative constitutionalism to become interdisciplinary, comparatists would do well to attend,intra disciplinarily, to private law’s effects upon constitutional interpretation. -

CHILD SUPPORT: by JUDICIAL DECISION by LEGISLATION? (Pt

REFORM OF THE LAW CHILD SUPPORT: BY JUDICIAL DECISION BY LEGISLATION? (Pt. I) Alastair Dissett-Johnson* Dundee This isa two-partarticle. Partone analyses the recent Supreme Court ofCanada decision in Willick and the Provincial Appeal Court decisions in L6vesque and Edwards on the issue ofassessing child support. Part two examines the British Child Support Acts 1991-5, which introduced an administrative formula driven method ofassessing child support, and the Canadian Federal/Provincial Family Law Committees Report Recommendations on Child Support. The merits and problems associated with administrative andjudicial methods ofassessing child support are examined and contrasted. Il s'agit d'un article en deux parties. La première partie analyse la décision récente de la Cour suprême du Canada dans l'affaire Willick, ainsi que les décisions de la Cour d'appelprovinciale dans les affaires Lévesque etEdward qui évaluent laprotection sociale de l'enfant. La secondepartie examine, d'unepart, les Child Support Acts britanniques (Lois sur la protection sociale de l'enfant) votées de 1991 à 1995 et quiontintroduit des moyens administratifs, basés surune formule, permettant d'évaluer laprotection sociale de l'enfant et, d'autre part, le Rapport des comités sur la législationfamilialefédérale/provinciale canadienne et les recommandations concernant la protection sociale de l'enfant. Les aspects positifs et négatifsliésaux méthodesadministratives etjudiciairesd'évaluation de la protection sociale de l'enfant sont examinés. I. Introduction .... ........ -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

Exception to Or Exemplar of Canada's Family Policy?

CANADIAN SAME-SEX MARRIAGE LAW Canada’s Same-Sex Marriage Law; Exception to or Exemplar of Canada’s Family Policy? Hilary A. Rose H. A. Rose Concordia University Dept. of Applied Human Sciences, VE-321.02 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West, Montreal, QC Canada H3G 1M8 CANADIAN SAME-SEX MARRIAGE LAW 2 Abstract Family policy in Canada is primarily concerned with assisting parents raise their children. This fairly singular approach to family policy is ironic given that Canada does not have a nationally- coordinated family policy. The development of a national family policy has been hampered by Canada’s decentralized governmental structure (i.e., federal and provincial, as well as territorial, governments) and other factors such as diverse geography and different traditions (e.g., a tradition of common law in English Canada, and civil law in Quebec). A recent addition to Canada’s family policy is Bill C-38, The Civil Marriage Act (2005), the law legalizing same-sex marriage. To put Canada’s same-sex marriage law into context, this article presents some preliminary statistics about same-sex marriage in Canada, and considers whether same-sex marriage legislation is a good example of Canadian family policy, or an exception to the rule that Canadian family policy focuses primarily on helping parents socialize their children. Key words: same-sex marriage, legislation, family policy, parenting, children CANADIAN SAME-SEX MARRIAGE LAW 3 Introduction Family policy is largely a 20th century invention. It developed first in Europe and spread over the course of the century to North America and other parts of the world (e.g., Australia, China, Japan). -

Familysource®

FamilySource® What’s in FamilySource® CASE LAW • Western Weekly Reports (W.W.R.) 1911- report series of other commercial • Historical Report Series publishers, including Quebec cases of FamilySource contains all full text cases dealing national importance. These law report • Alberta Law Reports (Alta. L.R.) 1908-33 with family law from the Westlaw Canada case series include: Decisions published law collection. This collection includes: • Canadian Cases on the Law of in major law report series of other Securities (C.C.L.S.) 1994-1998 commercial publishers, including • Complete coverage of reported • Canadian Intellectual Property Quebec cases of national importance. Canadian court decisions from the Reports (C.I.P.R.) 1984-90 These law report series include: common law provinces and Quebec cases of national importance, from • Canadian Reports, Appeal Cases • A.R. Alberta Reports 1986 and continuing forward (C.R.A.C.) 1871-78; 1912-13 • Alta. L.R.B.R. Alberta Labour Relations • Complete coverage of reported Supreme • Coutlee’s Canada Supreme Court Board Reports Court of Canada and Privy Council Cases (Cout. S.C.) 1875-1906 • B.C.A.C. British Columbia Appeal Cases decisions originating in any province • Eastern Law Reporter (E.L.R.) 1906-14 • C.C.C. Canadian Criminal Cases or territory from 1876 forward • Fox Patent Cases (Fox Pat.C.) 1940-71 • C.H.R.R. Canadian Human Rights Reporter • Complete coverage of Federal Court • Maritime Provinces Reports • C.I.R.B. Canada Industrial Relations Board decisions reported in the Federal Court (M.P.R.) 1929-68 • C.L.L.C. Canadian Labour Law Cases Reports from 1971 forward, and of the • New Brunswick Reports (N.B.R.) 1867-1929 Exchequer Court from 1875 through • C.L.R.B.R. -

Interacting with Separating, Divorcing, Never-Married Parents and Their Children

Association of Family and Conciliation Courts An Educator’s Guide: Interacting with Separating, Divorcing, Never-Married Parents and Their Children © 2009 Association of Family and Conciliation Courts AN EDUCATOR’S GUIDE: INTERACTING WITH SEPARATING, DIVORCING, NEVER- MARRIED PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN AFCC work group: Barbara Steinberg, Ph.D., Chair Nancy Olesen, Ph.D., Reporter Deborah Datz, LPC, NCSP Jake Jacobson, LCSW Naomi Kauffman, J.D. Hon. Emile Kruzick Shelley Probber, Psy.D. Gary Rick, Ph.D. With special thanks for contributed materials to Marsha Kline Pruett, PH.D., M.S.L. and The Smith Richardson Foundation, Inc. This guide was developed by the Association of Family and Conciliation Courts to help educators address the needs of separating, divorcing and never-married families and their children. AFCC is an international, multi- disciplinary organization comprised of attorneys, judges, mediators and mental health care providers who are dedicated to improving the lives of children and families through the resolution of family conflict. © 2009 Association of Family and Conciliation Courts TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction................................................................................................ 4 Children: Recognizing Their Challenges ................................................ 5 Parents: Facilitating Their Involvement ................................................. 7 Teachers: Staying Out of the Middle....................................................... 12 Family Court Professionals: Who Wants What -

Domestic Contracts

5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 1 FAMILY LAW FOR WOMEN IN ONTARIO Domestic Contracts All Women. One Family Law. Know your Rights. 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 2 Canadian Council of Muslim Women (CCMW) has prepared this information to provide Muslim women with basic information about family law in Ontario as it applies to Muslim communities. We hope to give answers to key questions about whether Muslim family laws can be used to resolve family law disputes in Canada. 2 DOMESTIC CONTRACTS 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 3 Domestic Contracts This booklet is meant to give you a basic understanding of legal issues. It is not a substitute for individual legal advice and assistance. If you are dealing with family law issues, get legal advice as soon as possible to protect your rights. For more information about how to find and pay for a family law lawyer, see FLEW’s booklet on “Finding Help with your Family Law Problem” on FLEW’s website at www.onefamilylaw.ca. Domestic contracts are legal agreements about intimate relationships. Marriage contracts, cohabitation agreements and separation agreements are different kinds of domestic contracts. You can use domestic contracts to set out certain terms for your relationship. You can also use a domestic contract to agree on your and your spouse’s rights and responsibilities in case your relationship ends. CANADIAN COUNCIL OF MUSLIM WOMEN (CCMW) 3 5020_CCMW_DC_v5.qxd:FLEW 4/17/09 3:54 PM Page 4 Domestic contracts are not legal unless they are in writing. -

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Family Service Delivery: Disease

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Family Service Delivery: Disease, Prevention, and TTreatment Noel Semple Law Commission of Ontario Family Law Process Projjectt Final Paper June 23, 2010 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction, Outline and Methodology ......................................................................... 3 I. A. Subject Matter: the Families and the Challenges Under Examination Here ......... 4 I. B. Unit of Analysis: Individual or Family? .................................................................. 5 I. C. The role of choice in the formation of family ......................................................... 6 I. D. Evaluative Tool: Cost-Benefit Analysis ................................................................. 9 I.D.1. Applying CBA Methodology to Family Challenges: Limitations ..................... 11 I.D.2. Applying CBA to Family Challenges: Potential ............................................. 13 II. Family Challenges ..................................................................................................... 14 II. A. Economic Vulnerability of Canadian Families.................................................... 16 II. B. Sacrifices in Earning Potential Undertaken in Intact Families............................ 19 II. B. 1. How Family Life can Lead to Sacrifices in Individual Earning Potential ..... 19 II. B. 2. Quantifying Parenting ................................................................................ 21 II. B. 3. Persistence of Gender Patterns ................................................................ -

Family Law and Immigrants a HANDBOOK on FAMILY LAW ISSUES in NEW BRUNSWICK

30 30 25 20 20 20 20 15 15 10 10 10 0 2014 2015 2016 Family Law and Immigrants A HANDBOOK ON FAMILY LAW ISSUES IN NEW BRUNSWICK PUBLIC LEGAL EDUCATION AND INFORMATION SERVICE OF NEW BRUNSWICK Public Legal Education and Information Service of New Brunswick (PLEIS-NB) is a non-profit charitable organization. Our mission is to provide plain language law information to people in New Brunswick. PLEIS-NB receives funding and in-kind support from Department of Justice Canada, the New Brunswick Law Foundation and the New Brunswick Office of the Attorney General. Project funding for the development of this booklet was provided by the Supporting Families Fund, Justice Canada. We wish to thank the many organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this handbook. We appreciate the suggestions for content that were shared by members of the Law Society of New Brunswick. We also thank the community agencies who work with newcomers and immigrants who helped us identify some unique issues that immigrants may face when dealing with family law matters. A special thanks as well to the individuals who participated in the professional review of the content, both from the perspective of legal accuracy, as well as relevance and cultural sensitivity. PLEIS-NB wishes to acknowledge the following agencies for giving permission to make use of, or adapt their existing information on family law and immigration status for this handbook: • Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO) • Family Law Education for Women (FLEW) • METRAC – Action on Violence • Government of Canada, Global Affairs Canada • Government of Canada, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship • Justice Education Society of BC • Legal Services Society British Columbia • Luke’s Place • Springtide Resources We have flagged this assistance throughout and the full list of agencies cited can be found on our Resources Cited section.