San Diego's 1935-1936 Exposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Shady Side: Escape the Heat to San Diego's Coolest Spots by Ondine Brooks Kuraoka

Publication Details: San Diego Family Magazine July 2004 pp. 28-29, 31 Approximately 1,400 words On the Shady Side: Escape the Heat to San Diego's Coolest Spots by Ondine Brooks Kuraoka During the dog days of summer, it’s tempting to hunker down inside until the temperature drops. Cabin fever can hit hard, though, especially with little ones. If we don’t have air conditioning we hit the mall, or stake out a booth at Denny’s, or do time at one of the wild pizza arcades when we’re desperate. Of course, we can always head to the beach. But we yearn for places where energetic little legs can run amok and avoid the burning rays. Luckily, there is a slew of family-friendly, shady glens nestled between the sunny stretches of San Diego. First stop: Balboa Park (www.balboapark.org ). The Secret is Out While you’re huffing a sweaty path to your museum of choice, the smiling folks whizzing by on the jovial red Park Tram are getting a free ride! Park in the lot at Inspiration Point on the east side of Park Blvd., right off of Presidents Way, and wait no longer than 15 minutes at Tram Central, a shady arbor with benches. The Tram goes to the Balboa Park Visitors Center (619-239-0512), where you can get maps and souvenirs, open daily from 9 a.m.. to 4 p.m. Continuing down to Sixth Avenue, the Tram then trundles back to the Pan American Plaza near the Hall of Champions Sports Museum. -

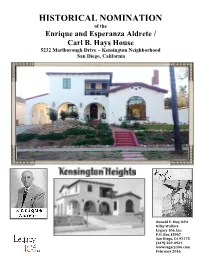

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B

HISTORICAL NOMINATION of the Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House 5232 Marlborough Drive ~ Kensington Neighborhood San Diego, California Ronald V. May, RPA Kiley Wallace Legacy 106, Inc. P.O. Box 15967 San Diego, CA 92175 (619) 269-3924 www.legacy106.com February 2016 1 HISTORIC HOUSE RESEARCH Ronald V. May, RPA, President and Principal Investigator Kiley Wallace, Vice President and Architectural Historian P.O. Box 15967 • San Diego, CA 92175 Phone (619) 269-3924 • http://www.legacy106.com 2 3 State of California – The Resources Agency Primary # ___________________________________ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # ______________________________________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial __________________________________ NRHP Status Code 3S Other Listings ___________________________________________________________ Review Code _____ Reviewer ____________________________ Date __________ Page 3 of 38 *Resource Name or #: The Enrique and Esperanza Aldrete / Carl B. Hays House P1. Other Identifier: 5232 Marlborough Drive, San Diego, CA 92116 *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County: San Diego and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a Location Map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad: La Mesa Date: 1997 Maptech, Inc.T ; R ; ¼ of ¼ of Sec ; M.D. B.M. c. Address: 5232 Marlborough Dr. City: San Diego Zip: 92116 d. UTM: Zone: 11 ; mE/ mN (G.P.S.) e. Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc.) Elevation: 380 feet Legal Description: Lots Three Hundred Twenty-three and Three Hundred Twenty-four of KENSINGTON HEIGHTS UNIT NO. 3, according to Map thereof No. 1948, filed in the Office of the County Recorder, San Diego County, September 28, 1926. It is APN # 440-044-08-00 and 440-044-09-00. -

Cassius Carter Centre Stage Darlene Gould Davies

Cassius Carter Centre Stage Darlene Gould Davies Cassius Carter Centre Stage, that old and trusted friend, is gone. The theatre in the round at The Old Globe complex in Balboa Park had its days, and they were glorious. Who can forget “Charlie’s Aunt” (1970 and 1977), or the hilarious 1986 pro- duction of “Beyond the Fringe”? Was there ever a show in the Carter that enchanted audiences more than “Spoon River Anthology” (1969)? A. R. Gurney’s “The Din- ing Room” (1983) was delightful. Craig Noel’s staging of Alan Ayckbourn’s ultra- comedic trilogy “The Norman Conquests” (1979) still brings chuckles to those who remember. San Diegans will remember the Carter. It was a life well lived. Cassius Carter Centre Stage, built in 1968 and opened in early 1969, was di- rectly linked to the original Old Globe Theatre of the 1935-36 California-Pacific International Exposition in Balboa Park. It was not a new building but a renovation of Falstaff Tavern that sat next to The Old Globe.1 In fact, until Armistead Carter Falstaff Tavern ©SDHS, UT #82:13052, Union-Tribune Collection. Darlene Gould Davies has served on several San Diego City boards and commissions under five San Diego mayors, is Professor Emerita of Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences at San Diego State University, and co-produced videos for the Mingei International Museum. She is currently a member of the Board of Directors of the San Diego Natural History Museum and has served as chair of the Balboa Park Committee. 119 The Journal of San Diego History Falstaff Tavern refreshments. -

Arciiltecture

· BALBOA PARK· CENTRAL MESA PRECISE PLAN Precise Plan • Architecture ARCIIlTECTURE The goal of this section is to rehabilitate and modify the architecture of the Central Mesa ina manner which preserves its historic and aesthetic significance while providing for functional needs. The existing structures built for the 1915 and the 1935 Expositions are both historically and architecturally significant and should be reconstructed or rehabilitated. Not only should the individual structures be preserved, but the entire ensemble in its original composition should be preserved and restored wherever possible. It is the historic relationship between the built and the outdoor environment that is the hallmark of the two Expositions. Because each structure affects its site context to such a great degree, it is vital to the preservation of the historic district that every effort be made to preserve and restore original Exposition building footprints and elevations wherever possible. For this reason, emphasis has been placed on minimizing architectural additions unless they are reconstructions of significant historical features. Five major types of architectural modifications are recommended for the Central Mesa and are briefly described below. 1. Preservation and maintenance of existing structures. In the case of historically significant architecture, this involves preserving the historical significance of the structure and restoring lost historical features wherever possible. Buildings which are not historically significant should be preserved and maintained in good condition. 2. Reconstructions . This type of modification involves the reconstruction of historic buildings that have deteriorated to a point that prevents rehabilitation of the existing structure. This type of modification also includes the reconstruction of historically significant architectural features that have been lost. -

MINUTES City of San Diego Park and Recreation Board BALBOA PARK

MINUTES City of San Diego Park and Recreation Board BALBOA PARK COMMITTEE November 6, 2008 Meeting held at: Mailing address is: Balboa Park Club, Santa Fe Room Balboa Park Administration 2150 Pan American Road 2125 Park Boulevard MS39 San Diego, CA 92101 San Diego, CA 92101-4792 ATTENDANCE: Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Jerelyn Dilno Jennifer Ayala Kathleen Hasenauer Vicki Granowitz Laurie Burgett Susan Lowery-Mendoza Mick Hager Mike Singleton Bruce Martinez Andrew Kahng David Kinney Mike McDowell Donald Steele (Arr. 5:40) CALL TO ORDER Chairperson Granowitz called the meeting to order at 5:37 P.M. APPROVAL OF MINUTES MSC IT WAS MOVED/SECONDED AND CARRIED UNANIMOUSLY TO APPROVE THE MINUTES OF THE OCTOBER 2, 2008 MEETING WITH CORRECTIONS TO REFLECT SINGLTON SECONDING ADOPTION ITEMS 201 AND 202 (KINNEY /DILNO 5-0) ABSTENTION- MCDOWELL REQUESTS FOR CONTINUANCES None NON AGENDA PUBLIC COMMENT Warren Simon, Chairperson of the Balboa Park Decembers Nights Committee, reported that there will be a few changes to this year’s venue. The Restaurant Taste will be located in the Palisades Parking lot adjacent to the Hall of Champions and a synthetic ice skating rink will also be located in the Palisades Parking Lot. The Plaza De Panama will host a spirits garden, and the Moreton Bay Fig Tree will be up-lighted. Shannon Sweeney representing Scott White Contemporary Art reported that the location approved by the Committee for the Bernar Venet sculpture requires a barrier to be placed around it for ADA compliance. Ms. Sweeney stated the barrier would detract from the sculpture and requested that the Committee reconsider placing the sculpture at the original requested location on the turf east of the San Diego Museum of Art. -

Casa Del Prado in Balboa Park

Chapter 19 HISTORY OF THE CASA DEL PRADO IN BALBOA PARK Of buildings remaining from the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, exhibit buildings north of El Prado in the agricultural section survived for many years. They were eventually absorbed by the San Diego Zoo. Buildings south of El Prado were gone by 1933, except for the New Mexico and Kansas Buildings. These survive today as the Balboa Park Club and the House of Italy. This left intact the Spanish-Colonial complex along El Prado, the main east-west avenue that separated north from south sections The Sacramento Valley Building, at the head of the Plaza de Panama in the approximate center of El Prado, was demolished in 1923 to make way for the Fine Arts Gallery. The Southern California Counties Building burned down in 1925. The San Joaquin Valley and the Kern-Tulare Counties Building, on the promenade south of the Plaza de Panama, were torn down in 1933. When the Science and Education and Home Economy buildings were razed in 1962, the only 1915 Exposition buildings on El Prado were the California Building and its annexes, the House of Charm, the House of Hospitality, the Botanical Building, the Electric Building, and the Food and Beverage Building. This paper will describe the ups and downs of the 1915 Varied Industries and Food Products Building (1935 Food and Beverage Building), today the Casa del Prado. When first conceived the Varied Industries and Food Products Building was called the Agriculture and Horticulture Building. The name was changed to conform to exhibits inside the building. -

Balboa Park Facilities

';'fl 0 BalboaPark Cl ub a) Timken MuseumofArt ~ '------___J .__ _________ _J o,"'".__ _____ __, 8 PalisadesBuilding fDLily Pond ,------,r-----,- U.,..p_a_s ..,.t,..._---~ i3.~------ a MarieHitchcock Puppet Theatre G BotanicalBuild ing - D b RecitalHall Q) Casade l Prado \ l::..-=--=--=---:::-- c Parkand Recreation Department a Casadel Prado Patio A Q SanD iegoAutomot iveMuseum b Casadel Prado Pat io B ca 0 SanD iegoAerospace Museum c Casadel Prado Theate r • StarlightBow l G Casade Balboa 0 MunicipalGymnasium a MuseumofPhotograph icArts 0 SanD iegoHall of Champions b MuseumofSan Diego History 0 Houseof PacificRelat ionsInternational Cottages c SanDiego Mode l RailroadMuseum d BalboaArt Conservation Cente r C) UnitedNations Bui lding e Committeeof100 G Hallof Nations u f Cafein the Park SpreckelsOrgan Pavilion 4D g SanDiego Historical Society Research Archives 0 JapaneseFriendship Garden u • G) CommunityChristmas Tree G Zoro Garden ~ fI) ReubenH.Fleet Science Center CDPalm Canyon G) Plaza deBalboa and the Bea Evenson Fountain fl G) HouseofCharm a MingeiInternationa l Museum G) SanDiego Natural History Museum I b SanD iegoArt I nstitute (D RoseGarden j t::::J c:::i C) AlcazarGarden (!) DesertGarden G) MoretonBay Ag T ree •........ ••• . I G) SanDiego Museum ofMan (Ca liforniaTower) !il' . .- . WestGate (D PhotographicArts Bui lding ■ • ■ Cl) 8°I .■ m·■ .. •'---- G) CabrilloBridge G) SpanishVillage Art Center 0 ... ■ .■ :-, ■ ■ BalboaPar kCarouse l ■ ■ LawnBowling Greens G 8 Cl) I f) SeftonPlaza G MiniatureRail road aa a Founders'Plaza Cl)San Diego Zoo Entrance b KateSessions Statue G) War MemorialBuil ding fl) MarstonPoint ~ CentroCu lturalde la Raza 6) FireAlarm Building mWorld Beat Cultura l Center t) BalboaClub e BalboaPark Activ ity Center fl) RedwoodBrid geCl ub 6) Veteran'sMuseum and Memo rial Center G MarstonHouse and Garden e SanDiego American Indian Cultural Center andMuseum $ OldG lobeTheatre Comp lex e) SanDiego Museum ofArt 6) Administration BuildingCo urtyard a MayS. -

St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House: Draft Nomination

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: St. Bartholomew’s Church and Community House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 325 Park Avenue (previous mailing address: 109 East 50th Street) Not for publication: City/Town: New York Vicinity: State: New York County: New York Code: 061 Zip Code: 10022 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival Into Balboa Park

Inspired by Mexico: Architect Bertram Goodhue Introduces Spanish Colonial Revival into Balboa Park By Iris H.W. Engstrand G. Aubrey Davidson’s laudatory address to an excited crowd attending the opening of the Panama-California Exposition on January 1, 1915, gave no inkling that the Spanish Colonial architectural legacy that is so familiar to San Diegans today was ever in doubt. The buildings of this exposition have not been thrown up with the careless unconcern that characterizes a transient pleasure resort. They are part of the surroundings, with the aspect of permanence and far-seeing design...Here is pictured this happy combination of splendid temples, the story of the friars, the thrilling tale of the pioneers, the orderly conquest of commerce, coupled with the hopes of an El Dorado where life 1 can expand in this fragrant land of opportunity. G Aubrey Davidson, ca. 1915. ©SDHC #UT: 9112.1. As early as 1909, Davidson, then president of the Chamber of Commerce, had suggested that San Diego hold an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. When City Park was selected as the site in 1910, it seemed appropriate to rename the park for Spanish explorer Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, who had discovered the Pacific Ocean and claimed the Iris H. W. Engstrand, professor of history at the University of San Diego, is the author of books and articles on local history including San Diego: California’s Cornerstone; Reflections: A History of the San Diego Gas and Electric Company 1881-1991; Harley Knox; San Diego’s Mayor for the People and “The Origins of Balboa Park: A Prelude to the 1915 Exposition,” Journal of San Diego History, Summer 2010. -

Plaza De Panama

WINTER 2010 www.C100.org PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The Balboa Park Alliance The Committee of One Hundred, The Balboa Park Trust at the San Diego Foundation, and Friends of Balboa Park share a common goal: to protect, preserve, and enhance Balboa Park. These three non-profi t organizations have formed Our Annual Appeal Help restore the Plaza de Panama. Make a check The Balboa Park Alliance (BPAL). Functioning to The Committee of One Hundred and mail it to: as an informal umbrella organization for nonprofi t groups committed to the enhancement of the Park, THE COMMITTEE OF ONE HUNDRED BPAL seeks to: Balboa Park Administration Building 2125 Park Boulevard • Leverage public support with private funding San Diego, CA 92103-4753 • Identify new and untapped revenue streams • Cultivate and engage existing donors has great potential. That partnership must have the • Attract new donors and volunteers respect and trust of the community. Will the City • Increase communication about the value of Balboa grant it suffi cient authority? Will the public have the Park to a broader public confi dence to support it fi nancially? • Encourage more streamlined delivery of services to The 2015 Centennial of the Panama-California the Park and effective project management Exposition is only fi ve years away. The legacy of • Advocate with one voice to the City and other that fi rst Exposition remains largely in evidence: authorizing agencies about the needs of the Park the Cabrillo Bridge and El Prado, the wonderful • Provide a forum for other Balboa Park support California Building, reconstructed Spanish Colonial groups to work together and leverage resources buildings, the Spreckels Organ Pavilion, the Botanical Building, and several institutions. -

The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W

The Journal of San Diego History SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Winter 1990, Volume 36, Number 1 Thomas L. Scharf, Editor The Making of the Panama-California Exposition, 1909-1915 by Richard W. Amero Researcher and Writer on the history of Balboa Park Images from this article On July 9, 1901, G. Aubrey Davidson, founder of the Southern Trust and Commerce Bank and Commerce Bank and president of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, said San Diego should stage an exposition in 1915 to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. He told his fellow Chamber of Commerce members that San Diego would be the first American port of call north of the Panama Canal on the Pacific Coast. An exposition would call attention to the city and bolster an economy still shaky from the Wall Street panic of 1907. The Chamber of Commerce authorized Davidson to appoint a committee to look into his idea.1 Because the idea began with him, Davidson is called "the father of the exposition."2 On September 3, 1909, a special Chamber of Commerce committee formed the Panama- California Exposition Company and sent articles of incorporation to the Secretary of State in Sacramento.3 In 1910 San Diego had a population of 39,578, San Diego County 61,665, Los Angeles 319,198 and San Francisco 416,912. San Diego's meager population, the smallest of any city ever to attempt holding an international exposition, testifies to the city's extraordinary pluck and vitality.4 The Board of Directors of the Panama-California Exposition Company, on September 10, 1909, elected Ulysses S. -

Tapestry of Time

Tapestry of Time From the Friends of Balboa Park Updated November 2010 Table of Authors Letter from Our Founder, Betty Peabody 4, 5 Allen, Grace Bentley 93 Amos, Martha f. 28 Anderson, Phyllis D. 91 Atherton, Debra 105 Atherton, May 17 Bennett, Kay Mason 77 Benton, Mariella 30 Borthwick, Georgia 11 Brown, Margaret 70 Butler, Ardith Lundy 47 Butler, Colornel Richard D. 45 Butorac, Kathryn 84 Cardua, Harney M. Jr. 38 Cash, John C. 9 Conlee, Roger 108 Cooper, Barbara 99 Davies, Darlene G. 96 Davies, Vince 66 Dose, Betty Curtis 69 Dr. Rufus Anton Schneiders 56 Earnest, Sue Ph.D 20 Echis, Ellen Renelle 33 Ehrich, Nano Chamblin 75 Engle, Mrs. Margaret 86 Evenson, Bea 106 Faulconer, Thomas P. 13 Fisk, Linda L. 23 Fry, Lewis W. 58 Giddings, Annie & Donald 18 Green, Don 87 Hankins, Thelma Larsen 53 Herms, Bruce F. 63 Hertzman, Sylvia Luce 78 Howard, RADM J.L. 43 Johnson, Cecelia cox 98 Jones, Barbara S. 40 Kenward, Frances Wright 34, 51 Kirk, Sandra Jackson 104 Klauber, Jean R. 6 Klauber, Phil 14, 36 Klees, Bob 89 Kooperman, Evelyn Roy 102 Lathrop, Chester A. 88 Lee, CDR Evelyn L. Schrader 100 Logue, Camille Woods 72 Marston, Hamilton 25 McFall, Gene 31 McKewen, Barbara Davis 90 Meads, Betty 95 Menke, Pat & Bob 94 Minchin, Mrs. Paul 68 Minskall, Jane 35 Mitchell, Alfred R. 29 Moore, Floyd R. 101 Neill, Clarence T. “Chan” 67 Oberg, Cy 74 Pabst, Dick 42 Pabst, Katherine 50 Phair, Patti 92 Porter, Francis J. Jr. 85 Pyle, Cynthia Harris 97 Richardson, Joe 79 Roche, Francis 82 Roche, Merna Phillips 60 Sadler, Mary M.