Mini Golf Course at Comedy Clubs, Even Though I Did Stand-Up for Twelve Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

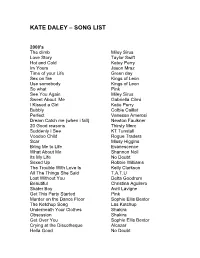

Kate Daley – Song List

KATE DALEY – SONG LIST 2000's The climb Miley Sirus Love Story Taylor Swift Hot and Cold Katey Perry Im Yours Jason Mraz Time of your Life Green day Sex on fire Kings of Leon Use somebody Kings of Leon So what Pink See You Again Miley Sirus Sweet About Me Gabriella Cilmi I Kissed a Girl Katie Perry Bubbly Colbie Caillat Perfect Vanessa Amerosi Dream Catch me (when i fall) Newton Faulkner 20 Good reasons Thirsty Merc Suddenly I See KT Tunstall Voodoo Child Rogue Traders Scar Missy Higgins Bring Me to Life Evanescence What About Me Shannon Noll Its My Life No Doubt Sexed Up Robbie Williams The Trouble With Love Is Kelly Clarkson All The Things She Said T.A.T.U Lost Without You Delta Goodrem Beautiful Christina Aguilero Skater Boy Avril Lavigne Get This Party Started Pink Murder on the Dance Floor Sophie Ellis Bextor The Ketchup Song Las Ketchup Underneath Your Clothes Shakira Obsession Shakira Get Over You Sophie Ellis Bextor Crying at the Discotheque Alcazar Hella Good No Doubt Lets Get Loud Jennifer Lopez Don’t Stop Moving S Club 7 Cant Get you Out of My Head Kylie Minogue I’m Like a Bird Nelly Fertado Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi Fallin’ Alicia Keys I Need Somebody Bardot Lady marmalade Moulin Rouge Drops of Jupiter Train Out of Reach Gabrielle (Bridgett Jones Dairy) Hit em up in Style Blu Cantrell Breathless The Corrs Buses and trains Bachelor Girl Shine Vanessa Amorosi What took you so long Emma B Overload Sugarbabes Cant Fight the Moonlight Leeann Rhymes (Coyote Ugly) Sunshine on a Rainy Day Christine Anu On a Night Like This -

1998 Literary Review (No

Whittier College Poet Commons Greenleaf Review Student Scholarship & Research 4-1998 1998 Literary Review (no. 12) Sigma Tau Delta Follow this and additional works at: https://poetcommons.whittier.edu/greenleafreview Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons A SIGMA TAU DELTA PUBLICATION Number 12 00 A SIGMA TAU DELTA PUBLICATION 1998 Literary Review NUMBER 12 APRIL, 1998 Table of Contents Fiction Cherry Pink & Apple Blossom White 8 Dimas Diaz A Story About What Happened to Jezebel Flatch 14 Nicole Coates Burton Disclaimer 22 Salvador Plascencia Sunkist Days 30 Salvador Plascencia Placental Pleasures 31 Krista Whyte Play 35 Adain Pava, Seventy-Three Seconds 44 Devlin Grunloh Poetry POETRY BY JEFF CAIN Thursday, 8:30 50 Bicycle Ride 51 POETRY BY TONI PANETTA He cries the tears that I cannot 52 POETRY BY DAWN FINLEY Walking Home From a 54 Friend's House II 54 I Have My Own Bathroom Now 54 Whitman Smokes a Marlboro Red 55 -2- POETRY BY ART RICH Who Cares? 56 The Rock 57 potential 57 First Prize 58 Cemetery Clock 59 Beyond Reflection 60 POETRY BY LUCY LOZANO Incubation 61 My Son Is Four Today 62 Spasm 63 POETRY BY DAGOBERTO LOPEZ Evening 64 POETRY BY ELIZABETH FREUDENTHAL Ambition 65 My Tenth Rosh Hashannah 66 EPIC 67 POETRY BY ALISON OUTSCHOORN Existentialism 68 Non-Fiction Le Problème Philosophique de l'Inferno de Dante 72 Demian Marienthal Roots 79 Michael Sariniento A Blameless Genocide 84 Sean Riordan Relativity: A Relative Perspective on the Relativity of Relating -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Columbia Poetry Review Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Poetry Review Publications Spring 4-1-2014 Columbia Poetry Review Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr Part of the Poetry Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Poetry Review" (2014). Columbia Poetry Review. 27. https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cpr/27 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Poetry Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. For more information, please contact [email protected]. review• columbiapoetryreview no. 27 Columbia Poetry Review is published in the spring of each year by the Department of Creative Writing, Columbia College Chicago, 600 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, 60605. SUBMISSIONS Our reading period extends from July 1 to November 1. Please submit up to 5 pages of poetry (one poem per page) during our reading period via Submittable: http://columbiapoetry. submittable.com/submit. The cost of the submission through Submittable is $3.00. PURCHASE INFORMATION Single copies are available for $10.00, $13.00 outside the U.S. but within North America, and $16.00 outside North America. Please send personal checks or money orders made out to Columbia Poetry Review to the above address. You may also purchase online at http://english.colum.edu/cpr. WEBSITE INFORMATION Columbia Poetry Review’s website is at http://english.colum.edu/cpr. -

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited by Nicholas Dovellos A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor (Deceased): Martin Schönfeld, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Alex Levine, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Govindan Parayil, Ph.D. Michael Morris, Ph.D. George Philippides, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 7, 2020 Key Words: Climate Ethics, Actionability, Psychoanalysis, Econo-Philosophy, Productive Orientation, Biophilia, Necrophilia, Pathology, Narcissism, Alienation, Interiority Copyright © 2020 Nicholas Dovellos Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Part I: The Current Climate Conversation: Work and Analysis of Contemporary Ethicists ........ 13 Chapter 1: Preliminaries ............................................................................................................ 16 Section I: Cape Town and Totalizing Systems ............................................................... 17 Section II: A Lack in Step Two: Actionability ............................................................... 25 Section III: Gardiner’s Analysis .................................................................................... -

Melania's Pith Helmet

Volume 10 (2019): Melania’s Pith Helmet: A Critical View of Her African Safari Relevant Rhetoric, Vol. 10 (2019): “Melania’s Pith Helmet” Terry Ownby Associate Professor Department of Communication, Media, and Persuasion Idaho State University [email protected] 2 Relevant Rhetoric, Vol. 10 (2019): “Melania’s Pith Helmet” Matt A.J. https://www.flickr.com/photos/cornstalker/ Barely entering the eighth month of his tumultuous and questionable presidency, Donald Trump found himself facing his amoral ambiguity on a televised global platform. After more than forty-eight hours had elapsed since the khaki-clad, tiki-torch wielding white nationalists marched across the University of Virginia campus and participated deadly violence the following day, Trump finally stepped in front of the cameras only to blame both sides of the racial conflict occurring in the rural hamlet of Charlottesville. His ambivalence and refusal to denounce overt racism perpetrated by his white populist base reinforced his public perception as being racist himself. Although Trump claims to be “the least racist person,” his words and actions over the decades speak for themselves.1 In a 2018 New York Times opinion article, David Leonhardt and Ian Prasad Philbrick assembled a conclusive list of his known racist comments.2 Thus, it could be that this notion of perception is really an actuality. Whether reality of “perception,” this aspect of the president taints those individuals within his orbits of influence, whether they are advisors, friends, or family. For some individuals and some news media outlets, assumptions might be made regarding those closest to the president, namely his family members. -

Romantic Comedy-A Critical and Creative Enactment 15Oct19

Romantic comedy: a critical and creative enactment by Toni Leigh Jordan B.Sc., Dip. A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University June, 2019 Table of Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgements iii Dedication iv Exegesis 1 Introduction 2 The Denier 15 Trysts and Turbulence 41 You’ve Got Influences 73 Conclusion 109 Works cited 112 Creative Artefact 123 Addition 124 Fall Girl 177 Our Tiny, Useless Hearts 259 Abstract For this thesis, I have written an exegetic complement to my published novels using innovative methodologies involving parody and fictocriticism to creatively engage with three iconic writers in order to explore issues of genre participation. Despite their different forms and eras, my subjects—the French playwright Molière (1622-1673), the English novelist Jane Austen (1775-1817), and the American screenwriter Nora Ephron (1941-2012)—arguably participate in the romantic comedy genre, and my analysis of their work seeks to reveal both genre mechanics and the nature of sociocultural evaluation. I suggest that Molière did indeed participate in the romantic comedy genre, and it is both gender politics and the high cultural prestige of his work (and the low cultural prestige of romantic comedy) that prevents this classification. I also suggest that popular interpretations of Austen’s work are driven by romanticised analysis (inseparable from popular culture), rather than the values implicit in the work, and that Ephron’s clever and conscious use of postmodern techniques is frequently overlooked. Further, my exegesis shows how parody provides a productive methodology for critically exploring genre, and an appropriate one, given that genre involves repetition—or parody—of conventions and their relationship to form. -

Racer Bible 2020

MARCH 12-14 Gravel/Mountain/Stage Racing EVENT DESCRIPTIONS A LITTLE HISTORY TRUE GRIT GRAVEL EPIC TRUE GRIT MOUNTAIN EPIC As with most great events, this race has humble beginnings. This gravel course is worthy of the True Grit title. Inspired by the Congratulations for taking on one of the toughest The course was concieved by The Race Director, Cimarron new True Grit Lauf Gravel Bike, the course is 80% off-road, 84 mountain bike races in North America. The tag line Long Chacon, back in 2008 as a way to link up the great trails in the miles, and 9000 ft of climbing. Pure Gravel Bliss! . Tough and Technical is no joke. St George area. Cimarron is trained as a landscape architect and You will be challenged at every turn and treated to amazing For 2020 we are able to offer 3 distance of this course - 100 Epic, worked for the BLM establishing the area trails before heading backcountry landscapes seldom seen, even by locals. This course 50 Epic , & 15 Challange . The main loop is our Epic 50. into private practice. She wanted to create an event that would is no “Grinder.” Out the gate you will be navigating a rough dry showcase the amazing terrain and bring people from all over The race will start and finish in downtown Santa Clara. wash, step burst hills and a bit of single track. Once you get to the country. The first race launched, after years of envirnmental The first mile will be on pavement past tree lined shops Curly Hollow rd, expect to cllimb. -

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality

Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 Thursday 12 April 2012 10:00 Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers St Georges Road St Annes on Sea Lancashire FY8 2AE Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers (Fine Art, Antiques, Jewellery, Gold & Silver, Porcelain and Quality Collectables Day 1 ) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 14 A Russian Silver And Cloisonne 9ct Gold Diamond & Iolite Cluster Enamel Salt. Unusual angled Ring, Fully Hallmarked, Ring Size shape. Finely enamelled in two T. tone blue, green red & white and Estimate: £80.00 - £90.00 with silver gilt interior. Moscow 84 Kokoshnik mark. (1908-1917). Maker probably Henrik Blootenkleper. Also French import mark. Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 Lot: 15 9ct White Gold Diamond Tennis Lot: 2D Bracelet, Set With Three Rows A Russian 14ct Gold Eastern Of Round Cut Diamonds, Fully Shaped Pendant Cross. 56 mark Hallmarked. & Assay Master RK (in cyrillic). Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Maker P.B. Circa 1900. 2" in length. 4 grams. Estimate: £80.00 - £120.00 Lot: 16 9ct Gold Opal And Diamond Stud Lot: 8D Earrings. Pear Shaped Opal With Three Elegant Venetian Glass Diamond Chips. Vases Overlaid In Silver With Estimate: £35.00 - £45.00 Scenes Of Gondolas And Floral Designs. Two in taupe colour and a larger one in green. Estimate: £30.00 - £40.00 Lot: 17 Simulated Pearl Necklace, White Lot: 10 Metal Clasp. Platinum Diamond Stud Earrings, Estimate: £25.00 - £30.00 Cushion Shaped Mounts Set With Princess Cut Diamonds, Fully Hallmarked, As New Condition. Estimate: £350.00 - £400.00 Lot: 18 9ct Gold Sapphire Ring, The Lot: 12 Central Oval Sapphire Between Large 18ct Gold Diamond Cross, Diamond Set Shoulders, Ring Mounted With 41 Round Modern Size M, Unmarked Tests 9ct. -

Sebastopol E-Edition

Follow us on Sebastopol December 11, 2020 12 Pages Sign up for the FREE e-Edition Sebastopol and get the latest local news Established delivered to your mailbox Quote of the week: 2020 Christmas is a necessity. Friedman’s Home Improvement There has to be at least one day of the year to remind us that we’re here for something else besides ourselves. Senior center keeps seniors safe and connected -Eric Severide Guess Who? I am an actress born in Georgia on December 10, 1985. I gained fame as a child star on a popular family sitcom and also as a child model. I went on to be the headliner in a Disney series and its spin-off. My name is a type of bird. Answer: Raven-Symoné Answer: Inside this issue Teachable moments 2 Mudflow losses 2 Climate activists summit 2 Stay at home order 2 The Power of Adversity 3 Family Justice Center 3 Spread holiday cheer 3 Know the facts 4 PG&E uses helicopter saw 4 Virtual poetry slam 4 Sebastopol History 7 Military ways 7 Bell ringers needed 7 Top-Volunteers at the Sebastopol Senior Center load their cars with meals to be delivered to area sen- Reduce wildfire risk 10 iors. The center delivers 800 meals per week. Rural well-owners 12 Right-Steve Annala leaves the Sebastopol Senior Center on his way to deliver meals to area seniors. Slam 2020 12 Photos courtesy of Sebastopol Senior Center Café Espresso By Brandon McCapes With over 200 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Sonoma County each day, staff and volunteers at the Feature of the week Sebastopol Senior Center have been working to keep the most vulnerable safe and connected to services throughout the pandemic. -

Two Day Fine Arts, Antiques, Jewellery, Silver, and Quality Collectables Sale - Day One Thursday 09 February 2012 10:00

Two Day Fine Arts, Antiques, Jewellery, Silver, and Quality Collectables Sale - Day One Thursday 09 February 2012 10:00 Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers St Georges Road St Annes on Sea Lancashire FY8 2AE Gerrards Auctioneers & Valuers (Two Day Fine Arts, Antiques, Jewellery, Silver, and Quality Collectables Sale - Day One) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Lot: 9 A Quality Japanese Cloisonne 18ct Gold Single Stone Diamond Enamel on White Metal Serving Ring, Illusion Set Round Cut Dish, white metal tests silver, Diamond, Stamped 18ct, Ring square shape with gently sloping Size M. inward sides, nicely enamelled in Estimate: £200.00 - £250.00 pink and green with a flowering Chrysanthemum on a white background, the reverse enamelled in black, makers label to the reverse for the 'Ando Cloisonne Co. of Tokyo, measuring 7 inches square. Lot: 9D An Oriental Green Jade and Estimate: £60.00 - £80.00 Sterling Silver Pendant. Oval shape decorated with a silver lily leaf and tendrils on which sits a Lot: 3 silver frog. The ring suspension A Highly Desirable German Silver marked '925'. 2 inches long. and Enamel Brooch, of stylish Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 concave triangular shape, the main body enamelled in a spectrum of colour (navy blue, pink, green, white and lemon), marked to the reverse '935, K Lot: 10 and L', for Kordes and Lichtenfels 9ct Gold Rope Chain, fully of Pforzheim hallmarked, measuring 28 inches Estimate: £40.00 - £60.00 long and weighing 21.9 grams. Estimate: £200.00 - £300.00 Lot: 4 An Unusual and Very Well Made Walnut and Silver Moneybox, in the realistic shape of a post box, the base unscrewing, vacant silver plaque below the post box Lot: 11 opening, hallmarked for A Quality Silver Bookmark, Birmingham 1993, for Douglas featuring a realistically modelled Pell, measuring 4½ inches owl perched on top of an oval high.