The Ice Shelf of Petermann Gletscher, North Greenland, and Its Connection to the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty-First Century Response of Petermann Glacier, Northwest Greenland to Ice Shelf Loss

Journal of Glaciology Twenty-first century response of Petermann Glacier, northwest Greenland to ice shelf loss Emily A. Hill1* , G. Hilmar Gudmundsson2 , J. Rachel Carr1, Chris R. Stokes3 2 Article and Helen M. King 1 *Present address: Department of Geography School of Geography, Politics, and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK; and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria 2Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 8ST, University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 8ST, UK. UK and 3Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK Cite this article: Hill EA, Gudmundsson GH, Carr JR, Stokes CR, King HM (2021). Twenty- Abstract first century response of Petermann Glacier, Ice shelves restrain flow from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Climate-ocean warming northwest Greenland to ice shelf loss. Journal could force thinning or collapse of floating ice shelves and subsequently accelerate flow, increase of Glaciology 67(261), 147–157. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/jog.2020.97 ice discharge and raise global mean sea levels. Petermann Glacier (PG), northwest Greenland, recently lost large sections of its ice shelf, but its response to total ice shelf loss in the future Received: 16 June 2020 remains uncertain. Here, we use the ice flow model Úa to assess the sensitivity of PG to changes Revised: 13 October 2020 in ice shelf extent, and to estimate the resultant loss of grounded ice and contribution to sea level Accepted: 14 October 2020 First published online: 2 December 2020 rise. Our results have shown that under several scenarios of ice shelf thinning and retreat, removal of the shelf will not contribute substantially to global mean sea level (<1 mm). -

Seasonal Evolution of Supraglacial Lakes on a Floating Ice Tongue, Petermann Glacier, Greenland

Annals of Glaciology 59(76pt1) 2018 doi: 10.1017/aog.2018.9 56 © The Author(s) 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Seasonal evolution of supraglacial lakes on a floating ice tongue, Petermann Glacier, Greenland Grant J. MACDONALD,1 Alison F. BANWELL,2 Douglas R. MacAYEAL1 1Department of the Geophysical Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, CB2 1ER, UK ABSTRACT. Supraglacial lakes are known to trigger Antarctic ice-shelf instability and break-up. However, to date, no study has focused on lakes on Greenland’s floating termini. Here, we apply lake boundary/area and depth algorithms to Landsat 8 imagery to analyse the inter- and intraseasonal evolu- tion of supraglacial lakes across Petermann Glacier’s (81°N) floating tongue from 2014 to 2016, while also comparing these lakes to those on the grounded ice. Lakes start to fill in June and quickly peak in total number, volume and area in late June/early July in response to increases in air temperatures. However, through July and August, total lake number, volume and area all decline, despite sustained high temperatures. These observations may be explained by the transportation of meltwater into the ocean by a river, and by lake drainage events on the floating tongue. Further, as mean lake depth remains relatively constant during this time, we suggest that a large proportion of the lakes that drain, do so completely, likely by rapid hydrofracture. -

Research Cruise Report: Mission HLY031

Research Cruise Report: Mission HLY031 Conducted aboard USCGC Healy In Northern Baffi n Bay and Nares Strait 21 July –16 August 2003 Project Title: Variability and Forcing of Fluxes through Nares Strait and Jones Sound: A Freshwater Emphasis Sponsored by the US National Science Foundation, Offi ce of Polar Programs, Arctic Division Table of Contents Introduction by Chief Scientist . 4 Science Program Summary . 6 Science Party List . 7 Crew List . 8 Science Component Reports CTD-Rosette Hydrography . 9 Internally recording CTD . 29 Kennedy Channel Moorings . 33 Pressure Array . 41 Shipboard ADCP . 47 Bi-valve Retrieval . 51 Coring . 55 Seabeam Mapping . 65 Aviation Science Report . 71 Ice Report . 79 Weather Summary . 91 Inuit Perspective . 95 Photojournalist Perspective . 101. Website Log . 105 Chief Scientist Log . 111 Recommendations . .125 Introduction Dr. Kelly Kenison Falkner Chief Scientist Oregon State University In the very early hours of July 17, 2003, I arrived at collected via the ship’s Seabeam system and the underway the USCGC Healy moored at the fueling pier in St. John’s thermosalinograph system was put to good use throughout Newfoundland, Canada to assume my role as chief scientist much of the cruise. for an ambitious interdisciplinary mission to Northern Part of our success can be attributed to luck with Mother Baffi n Bay and Nares St. This research cruise constitutes Nature. Winds and ice worked largely in our favor as we the inaugural fi eld program of a fi ve year collaborative wound our way northward. Our winds were generally research program entitled Variability and Forcing of moderate and out of the south and the ice normal to light. -

The Shrinking Greenland Ice Sheet the Increasing Rate of Sea-Level Rise

The increasing rate of sea-level rise is one of the major pressing concerns associated with climate change. It has potentially severe consequences for over 200 million people who live on coastal flood plains around the world, as well as for the trillion dollars’ worth of assets lying less than one metre above current sea level. Reliable predictions of sea-level rise are essential for adaptation and mitigation; the largest uncertainty in these predictions currently comes from our lack of understanding of likely future change in the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. The shrinking Greenland ice Sheet four major outlet glaciers have grounding lines significantly below sea level, and only The Greenland Ice Sheet presently accounts for two of these (Petermann Glacier and 79°N about a quarter (0.5 mm yr−1) of global mean sea- Glacier) now flow out over the water in the level rise each year, and its contribution has more fjord to form a substantial floating tongue or than doubled in the past decade. Much of this shelf of ice. A third such glacier (Jakobshavn change has been due to increased ice discharge Isbræ) has recently lost its ice shelf, rapidly associated with the acceleration of outlet glaciers retreating back to its grounding line over the flowing into fjords in western and south-east- past decade. This is thought to have been ern Greenland. Higher ocean temperatures are due to an increase in ocean temperatures thought to have played a role. However, the beneath the floating portion of the glacier, circulation within Greenland’s fjords is not well and has resulted in a significant speeding up known, and the interaction between glacial ice of the glacial ice flux over land. -

Spatial Variation in Arctic Hare (Lepus Arcticus) Populations Around the Hall Basin

Spatial variation in Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) populations around the Hall Basin Fredrik Dalerum1,2,3, Love Dalén2,4, Christina Fröjd5, Nicolas Lecomte6, Åsa Lindgren5, Tomas Meijer2,7, Patricia Pecnerova2,4, Anders Angerbjörn2 1 Research Unit of Biodiversity, Department of Biology of Organisms and Systems, University of Oviedo, Spain 2 Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, Sweden 3 Mammal Research Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Pretoria, South Africa 4 Department of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Sweden 5 Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, Sweden 6 Canada Research Chair in Polar and Boreal Ecology and Centre d’Études Nordiques, Department of Biology, University of Moncton, Canada 7 Section for Wildlife Diseases, Swedish National Veterinary Institute, Travvägen 12A, 756 51 Uppsala, Sweden Published in Polar Biology, October 2017, Volume 40, Issue 10, pp 2113–2118 1 Abstract Arctic environments have relatively simple ecosystems. Yet, we still lack knowledge of the spatio- temporal dynamics of many Arctic organisms and how they are affected by local and regional processes. The Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) is a large lagomorph endemic to high Arctic environments in Canada and Greenland. Current knowledge about this herbivore is scarce and the temporal and spatial dynamics of their populations are poorly understood. Here we present observations on Arctic hares in two sites on north Greenland (Hall and Washington lands) and one adjacent site on Ellesmere Island (Judge Daly Promontory). We recorded a large range of group sizes from 1 to 135 individuals, as well as a substantial variation in hare densities among the three sites (Hall land: 0 animals / 100 km2, Washington land 14.5-186.7 animals / 100 km2, Judge Daly Promontory 0.18-2.95 animals / 100 km2). -

Download Download

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P. 334 – 348 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4735 Seal Occurrence and Habitat Use during Summer in Petermann Fjord, Northwestern Greenland Kate Lomac-MacNair,1,2 Martin Jakobsson,3 Alan Mix,4 Francis Freire,3 Kelly Hogan,5 Larry Mayer6 and Mari A. Smultea2 (Received 29 June 2017; accepted in revised form 30 May 2018) ABSTRACT. Ice-associated seals are considered especially susceptible and are potentially the first to modify distribution and habitat use in response to physical changes associated with the changing climate. Petermann Glacier, part of a unique ice-tongue fjord environment in a rarely studied region of northwestern Greenland, lost substantial sections of its ice tongue during major 2010 and 2012 calving events. As a result, changes in seal habitat may have occurred. Seal occurrence and distribution data were collected in Petermann Fjord and adjacent Nares Strait region over 27 days (2 to 28 August) during the multidisciplinary scientific Petermann 2015 Expedition on the icebreaker Oden. During 239.4 hours of dedicated observation effort, a total of 312 individuals were recorded, representing four species: bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus), hooded seal (Crystophora cristata), harp seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus), and ringed seal (Pusa hispida). Ringed seals were recorded significantly more than the other species (χ2 = 347.4, df = 3, p < 0.001, n = 307). We found significant differences between species in haul-out (resting on ice) behavior (χ2 = 133.1, df = 3, p < 0.001, n = 307). Bearded seals were more frequently hauled out (73.1% n = 49), whereas ringed seals were almost exclusively in water (93.9%, n = 200). -

Twenty-First Century Response of Petermann Glacier, Northwest Greenland to Ice Shelf Loss

Journal of Glaciology Twenty-first century response of Petermann Glacier, northwest Greenland to ice shelf loss Emily A. Hill1* , G. Hilmar Gudmundsson2 , J. Rachel Carr1, Chris R. Stokes3 2 Article and Helen M. King 1 *Present address: Department of Geography School of Geography, Politics, and Sociology, Newcastle University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK; and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria 2Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 8ST, University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE1 8ST, UK. UK and 3Department of Geography, Durham University, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK Cite this article: Hill EA, Gudmundsson GH, Carr JR, Stokes CR, King HM (2021). Twenty- Abstract first century response of Petermann Glacier, Ice shelves restrain flow from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Climate-ocean warming northwest Greenland to ice shelf loss. Journal could force thinning or collapse of floating ice shelves and subsequently accelerate flow, increase of Glaciology 67(261), 147–157. https://doi.org/ 10.1017/jog.2020.97 ice discharge and raise global mean sea levels. Petermann Glacier (PG), northwest Greenland, recently lost large sections of its ice shelf, but its response to total ice shelf loss in the future Received: 16 June 2020 remains uncertain. Here, we use the ice flow model Úa to assess the sensitivity of PG to changes Revised: 13 October 2020 in ice shelf extent, and to estimate the resultant loss of grounded ice and contribution to sea level Accepted: 14 October 2020 First published online: 2 December 2020 rise. Our results have shown that under several scenarios of ice shelf thinning and retreat, removal of the shelf will not contribute substantially to global mean sea level (<1 mm). -

The Morris Bugt Group (Middle Ordovician - Silurian) of North Greenland and Its Correlatives

The Morris Bugt Group (Middle Ordovician - Silurian) of North Greenland and its correlatives M. Paul Smith, Martin Sønderholm and Simon J. Tul! The Morris Bugt Group, originally proposed in western North Greenland, is now extendcd across the whole of North Greenland. One new formation, the Kap Jackson Formation, is described; it includes two members, the Gonioceras Bay and Troedsson Cliff Members, which correspond to earlier formations of the same names. In the Washington Land - western Peary Land region the group comprises the Kap Jackson, Cape Calhoun and Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formations. The Børglum River and Turesø Formations of the Peary Land - Kronprins Christian Land region are here added to the group. New data on the age of the formations based on conodont biostratigraphy are given, and correlations with Arctic Canada, East Greenland and Svalbard are discussed. M. P. S., Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, Cambridge CB23EQ, England. Present address: Geologisk Museum, øster Voldgade 5-7, DK-1350 København K, Denmark. M. S., Grønlands Geologiske Undersøgelse, øster Voldgade 10, DK-1350 København K, Denmark. S. J. T., Department ofGeology, University ofNoccingham, University Park, Notting ham NG72RD, England. Present address: Chapman & Hall, Il New Felter Lane, London EC4P 4EE, England. The Monis Bugt Group was erected by Peel & Hurst three members by Sønderholm & Harland (in prep.) (1980) to encompass the Gonioceras Bay, Troedsson who give full formal descriptions af these members. The Cliff, Cape Calhoun and Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formations. lower member of the Aleqatsiaq Fjord Formation cone These formations were originally described from Wash lates with the upper part of the Børglum River Forma ington Land (Troedsson, 1926, 1928; Koch, 1929a,b; tion. -

Terra Spies a Major Glacier Break-Up 23

Terra Spies a Major Glacier Break-up 23 On Aug. 5, 2010, an enormous chunk of ice broke off the Petermann Glacier along the northwestern coast of Greenland. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite captured these natural-color images of Petermann Glacier 18:05 UTC on August 5, 2010 (left), and 17:15 UTC on July 28, 2010 (right). The Terra image of the Petermann Glacier on August 5 was acquired almost 10 hours after the Aqua observation that first recorded the calving event. By the time Terra took this image, the oblong iceberg had broken free of the glacier and moved a short distance down the fjord. Problem 1 - From the scale of the two images, what is the approximate surface area of the portion of the glacier that broke-off in A) square kilometers? B) square miles if 1 km = 0.62 miles? Problem 2 - From the width of the break line in the August image, what was the speed of drift of the glacier fragment in kilometers/hour? Problem 3 - Assuming that the fragment is 1000 meters thick, what is the total volume of the fragment in cubic meters? Problem 4 - If one cubic meter of ice = 917 kilograms 1 gallon of water = 3.8 kg, what is the total amount of fresh water, in gallons, that will eventually be added to the ocean after it melts? Space Math http://spacemath.gsfc.nasa.gov Answer Key 26 Problem 1 - From the scale of the two images, what is the approximate surface area of the portion of the glacier that broke-off in A) square kilometers? B) square miles if 1 km = 0.62 miles? Answer: The length of the '25 km' line is about 17 mm so the scale is 1.5 km/mm. -

Possible Impacts of a 1000 Km Long Hypothetical Subglacial River Valley

Possible impacts of a 1000 km long hypothetical subglacial river valley towards Petermann Glacier in northern Greenland Christopher Chambers1, Ralf Greve1,2, Bas Altena3,4, and Pierre-Marie Lefeuvre3 1Institute of Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan 2Arctic Research Center, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan 3Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Norway 4Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research Utrecht, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands Correspondence: Christopher Chambers ([email protected]) Abstract. Greenland basal topographic data shows a segmented valley extending from Petermann Fjord into the centre of Greenland, however the locations of radar scan lines, used to create the bedrock topography data, indicate that valley seg- mentation is due to data interpolation. Therefore, as a thought experiment, simulations where the valley is opened are used to investigate its effects on basal water movement and distribution. The simulations indicate that the opening of this valley can 5 result in an uninterrupted water pathway from the interior to Petermann Fjord. Along its length, the path of the valley pro- gresses gradually down an ice surface slope causing a lowering of ice overburden pressure that could enable water flow along its path. The fact that the valley base appears to be relatively flat and follows a path near the interior ice divide that roughly intersects the east and west basal hydrological basins, is presented as evidence that its present day form may have developed in conjunction with an overlying ice sheet. Experiments where basal melting is increased solely within the deep interior near the 10 known large area of basal melting, result in an increase in the flux of water northwards along the entire valley. -

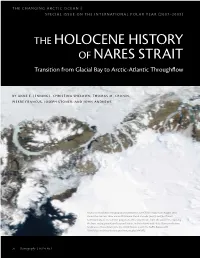

The Holocene History of Nares Strait Transition from Glacial Bay to Arctic-Atlantic Throughflow

THE CHANGING ARCTIC OCEAN | SpECIAL ISSUE ON THE IntERNATIONAL POLAR YEAr (2007–2009) THE HOLOCENE HISTORY OF NARES STRAIT Transition from Glacial Bay to Arctic-Atlantic Throughflow BY AnnE E. JEnnINGS, CHRISTINA SHELDON, THOMAS M. CRONIN, PIERRE FRANCUS, JOSEPH StONER, AND JOHN AnDREWS Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) image from August 2002 shows the summer thaw around Ellesmere Island, Canada (west), and Northwest Greenland (east). As summer progresses, the snow retreats from the coastlines, exposing the bare, rocky ground, and seasonal sea ice melts in fjords and inlets. Between the two landmasses, Nares Strait joins the Arctic Ocean (north) to Baffin Bay (south). From http://visibleearth.nasa.gov/view_rec.php?id=3975 26 Oceanography | Vol.24, No.3 ABSTRACT. Retreat of glacier ice from Nares Strait and other straits in the Nares Strait and the subsequent evolu- Canadian Arctic Archipelago after the end of the last Ice Age initiated an important tion of Holocene environments. In connection between the Arctic and the North Atlantic Oceans, allowing development August 2003, the scientific party aboard of modern ocean circulation in Baffin Bay and the Labrador Sea. As low-salinity, USCGC Healy collected a sediment nutrient-rich Arctic Water began to enter Baffin Bay, it contributed to the Baffin and core, HLY03-05GC, from Hall Basin, Labrador currents flowing southward. This enhanced freshwater inflow must have northern Nares Strait, as part of a study influenced the sea ice regime and likely is responsible for poor -

Curriculum Vitae: Anne E

CURRICULUM VITAE: ANNE E. JENNINGS Research Scientist III; INSTAAR Fellow Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research University of Colorado Boulder, CO 80309-450 Phone: 303-492-7621 Fax: 303-492-6388 Email: [email protected] Education 1989 PhD., Geology, University of Colorado, Boulder. 1986 M.Sc., Geology, University of Colorado, Boulder. 1980 B.S., Geology, Duke University. Professional and Educational Experience January 1, 2000- Present: Fellow, INSTAAR, University of Colorado, Boulder. Editor, Arctic, Antarctic and Alpine Research, October 2004 to present Research Interests Research interests include; 1) Holocene paleoceanography and sea-ice history of Greenland and Iceland shelves 2) glacial-marine sedimentation: stratigraphy, paleoenvironments, and glacial history on high latitude shelves (East Greenland, West Greenland, and Iceland); and 3) Modern foraminiferal distributions and ecology on high latitude shelves (Greenland, and Iceland). 4) Sub-ice shelf sedimentation and sub-ice shelf foraminifera in the Petermann Fjord, NW Greenland. 5) Baffin Bay and Labrador Sea LGM and deglaciation. Recent and Current International Collaboration Aslaug Geirsdóttir, Univ. of Iceland Colm O’Cofaigh, Durham University, UK Paul Knutz, GEUS, Denmark Marit-Solveig Seidenkrantz, Aarhus Univ., Claude Hillaire-Marcel, GEOTOP, CA DK Christof Pearce, Stockholm University, SW Guillaume St-Onge, Laval University, Quebec Karen Luise Knudsen, Aarhus Univ. DK Canada Alix Cage, Keele Univ. UK Anna Pienkowski, UNIS, Norway Teaching and Thesis Committees: 2017: Honors thesis committee for Blythe Befus. Geological Sciences. 2016: Honors thesis committee for Anna Klein, Geological Sciences. 2014: Member of Dissertation committee for Whitney Doss and member of MS committee for Hannah Grist, Geological Sciences. 2012-2014: Member of Disstertation committee for Ursula Quillmann.