Mckittrick, Casey. "Notes." Hitchcock's Appetites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Democracy Movement Comm 130F San Jose State U Dr

Case Study: Media Democracy Movement Comm 130F San Jose State U Dr. T.M. Coopman Okay for non-commercial use with attribution This Case Study This case study is a brief overview of a specific social movement and is designed to familiarize students with major large scale social movements. Media Democracy The Media Democracy Movement is not quite as significant as other movements we have examined, but it is important because it has grown along side and as a part of movements. Movements always create or try to influence or utilize the media. Media Democracy recognizes the pivotal role of media in the political process and recognizes that a commercial or state run media system will always side with incumbent power. Media democracy has two broad areas of focus (1) to reform and regulate existing media and (2) create viable alternative media. Media Democracy An central tenant of Media Democracy American mainstream media has an is corporate ownership and commercial investment in the status quo and tends demands influence media content, to vilify, mock, or ignore people and limiting the range of news, opinions, and organizations that fall outside its entertainment. definitions of what is legitimate. Jim Kuyper’s argues that most media The media is comprised of individuals operates with a narrow “liberal” and organizations that are self- comfort zone that cuts out discourse interested - the primary goal is most on the left and right. often profit - not fostering democracy. It is also notorious blind to this self- Advocates agitate for a more equal interest. distribution of economic, social, cultural, and information capital. -

LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: a Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and VS Naipaul

EnterText 1.3 LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: A Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul At first glance, the subjects under scrutiny may appear to have little in common with each other. A great deal has been written separately about the works of both Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul, but the objective of this article is to show how numerous parallels can be drawn between many of the recurrent ideas and issues that occur within their respective works. Whilst Naipaul refers to the cinema in many of his novels and short stories, his most sustained usage of the filmic medium is to be found in the 1971 work In a Free State. In this particular book, the films to which Naipaul makes repeated, explicit reference are primarily those of the film director Alfred Hitchcock. Furthermore, a detailed textual analysis shows that similarities exist between the thematic preoccupations that have informed the output of both men throughout much of their lengthy careers. As this article will demonstrate, the decision to contrast the works of these two men has, therefore, been far from arbitrary. Naipaul’s attraction to the world of cinema can be traced back to his childhood in Trinidad, an island where Hollywood films remained the predominant viewing fare throughout most of his formative years.1 The writer’s own comments in the “Trinidad” section of The Middle Passage bear this out: “Nearly all the films shown, apart from those in the first-run cinemas, are American and old. Favourites were shown again and Lynne Macedo: Alfred Hitchcock and V. -

Introduction to Carla Wilson's Curious Impossibilies: Ten Cinematic Riffs

Introduction to Curious Impossibilities: Ten Cinematic Riffs by Carla M. Wilson by James R. Hugunin The concealed essence of a phenomenon [herein, film] is often given by the past events that have happened to it, so that a concealed force continues to operate upon a phenomenon [film] as a kind of transcendental memory. — Philip Goodchild, Deleuze and Guattari (1996) True aesthetic innovation can only come from reworking and trans-forming existing imagery, ripping it from its original context and feeding it into new circuits of analogy. —Andrew V. Uroskie, “Between the Black Box and the White Cube” (2014) I remember the ashtrays. God, the number of cigarettes they burned up in the movies in those days. — “Don’t Even Try, Sam,” William H. Gass in Cinema Lingua, Writers Respond to Film (2004) I have been totally spellbound by cinema. Hitchcock, Max Ophuls, Bergman, Godard, Truffaut, Marker, Fellini, all have enriched my imagination. I take photographs. I’ve tried my hand at films. I’ve worked on the special effects in Hollywood films. I study the history of photography and film. I dig film noir. I write criticism. During its heyday, I read Screen, Screen Education, and Cahiers du cinema, relig- iously; carried Christian Metz’s The Imaginary Signifier (1977) around like some people do the Bible. Now I write fiction, fiction influenced by film. Early on, I noticed that the interaction between film and literature has been a rich one — writing influencing film, film influencing writing. An example of the latter I encoun- tered in college was American writer John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. -

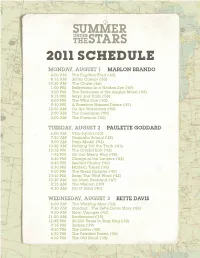

2011 Schedule

2011 SCHEDULE MONDAY, AUGUST 1 • MARLON BRANDO 6:00 AM The Fugitive Kind (’60) 8:15 AM Julius Caesar (’53) 10:30 AM The Chase (’66) 1:00 PM Reflections in a Golden Eye (’67) 3:00 PM The Teahouse of the August Moon (’56) 5:15 PM Guys and Dolls (’55) 8:00 PM The Wild One (’53) 9:30 PM A Streetcar Named Desire (’51) 12:00 AM On the Waterfront (’54) 2:00 AM The Freshman (’90) 4:00 AM The Formula (’80) TUESDAY, AUGUST 2 • PAULETTE GODDARD 6:00 AM Vice Squad (’53) 7:30 AM Dramatic School (’38) 9:00 AM Paris Model (’53) 10:30 AM Nothing But the Truth (’41) 12:15 PM The Crystal Ball (’43) 1:45 PM On Our Merry Way (’48) 3:30 PM Charge of the Lancers (’53) 4:45 PM Second Chorus (’40) 6:30 PM Modern Times (’36) 8:00 PM The Great Dictator (’40) 10:15 PM Reap The Wild Wind (’42) 12:30 AM An Ideal Husband (’47) 2:15 AM The Women (’39) 4:30 AM Pot O’ Gold (’41) WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 3 • BETTE davis 6:00 AM The Working Man (’33) 7:30 AM Stardust: The Bette Davis Story (’05) 9:00 AM Now, Voyager (’42) 11:00 AM Bordertown (’35) 12:45 PM 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (’32) 2:15 PM Juarez (’39) 4:30 PM The Letter (’40) 6:30 PM The Petrified Forest (’36) 8:00 PM The Old Maid (’39) 10:00 PM Jezebel (’38) 12:00 AM The Corn is Green (’45) 2:00 AM The Catered Affair (“56) 3:45 AM John Paul Jones (’59) 10:15 PM Bullitt (’68) 12:15 AM Junior Bonner (’72) 2:00 AM The Reivers (’69) 4:00 AM The Cincinnati Kid (’65) THURSDAY, AUGUST 4 • RONALD COLMAN 6:00 AM Lucky Partners (’40) 7:45 AM My Life with Caroline (’41) 9:15 AM The White Sister (’23) 11:30 AM Kiki (’26) 1:30 PM Raffles -

"Sounds Like a Spy Story": the Espionage Thrillers of Alfred

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions 4-29-2016 "Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969) Kimberly M. Humphries Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Humphries, Kimberly M., ""Sounds Like a Spy Story": The Espionage Thrillers of Alfred Hitchcock in Twentieth-Century English and American Society, from The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) to Topaz (1969)" (2016). Student Research Submissions. 47. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/47 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SOUNDS LIKE A SPY STORY": THE ESPIONAGE THRILLERS OF ALFRED HITCHCOCK IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND AMERICAN SOCIETY, FROM THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934) TO TOPAZ (1969) An honors paper submitted to the Department of History and American Studies of the University of Mary Washington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors Kimberly M Humphries April 2016 By signing your name below, you affirm that this work is the complete and final version of your paper submitted in partial fulfillment of a degree from the University of Mary Washington. You affirm the University of Mary Washington honor pledge: "I hereby declare upon my word of honor that I have neither given nor received unauthorized help on this work." Kimberly M. -

Annual Report, FY 2013

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING SEPTEMBER 30, 2013 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN OF CONGRESS for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2013 Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 CONTENTS Letter from the Librarian of Congress ......................... 5 Organizational Reports ............................................... 47 Organization Chart ............................................... 48 Library of Congress Officers ........................................ 6 Congressional Research Service ............................ 50 Library of Congress Committees ................................. 7 U.S. Copyright Office ............................................ 52 Office of the Librarian .......................................... 54 Facts at a Glance ......................................................... 10 Law Library ........................................................... 56 Library Services .................................................... 58 Mission Statement. ...................................................... 11 Office of Strategic Initiatives ................................. 60 Serving the Congress................................................... 12 Office of Support Operations ............................... 62 Legislative Support ................................................ 13 Office of the Inspector General ............................ 63 Copyright Matters ................................................. 14 Copyright Royalty Board ..................................... -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "Epilogue." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 159–163. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 08:18 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Epilogue itchcock and his works continue to experience life among generation Y Hand beyond, though it is admittedly disconcerting to walk into an undergraduate lecture hall and see few, if any, lights go on at the mention of his name. Disconcerting as it may be, all ill feelings are forgotten when I watch an auditorium of eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds transported by the emotions, the humor, and the compulsions of his cinema. But certainly the college classroom is not the only guardian of Hitchcock ’ s fl ame. His fi lms still play at retrospectives, in fi lm festivals, in the rising number of fi lm studies classes in high schools, on Turner Classic Movies, and other networks devoted to the “ oldies. ” The wonderful Bates Motel has emerged as a TV serial prequel to Psycho , illustrating the formative years of Norman Bates; it will see a second season in the coming months. Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour are still in strong syndication. Both his fi lms and television shows do very well in collections and singly on Amazon and other e-commerce sites. -

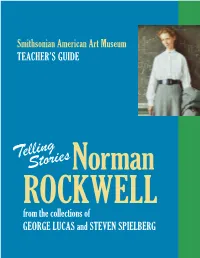

Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg

Smithsonian American Art Museum TEACHER’S GUIDE from the collections of GEORGE LUCAS and STEVEN SPIELBERG 1 ABOUT THIS RESOURCE PLANNING YOUR TRIP TO THE MUSEUM This teacher’s guide was developed to accompany the exhibition Telling The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 8th and G Streets, NW, Stories: Norman Rockwell from the Collections of George Lucas and above the Gallery Place Metro stop and near the Verizon Center. The museum Steven Spielberg, on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in is open from 11:30 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Admission is free. Washington, D.C., from July 2, 2010 through January 2, 2011. The show Visit the exhibition online at http://AmericanArt.si.edu/rockwell explores the connections between Norman Rockwell’s iconic images of American life and the movies. Two of America’s best-known modern GUIDED SCHOOL TOURS filmmakers—George Lucas and Steven Spielberg—recognized a kindred Tours of the exhibition with American Art Museum docents are available spirit in Rockwell and formed in-depth collections of his work. Tuesday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., September through Rockwell was a masterful storyteller who could distill a narrative into December. To schedule a tour contact the tour scheduler at (202) 633-8550 a single moment. His images contain characters, settings, and situations that or [email protected]. viewers recognize immediately. However, he devised his compositional The docent will contact you in advance of your visit. Please let the details in a painstaking process. Rockwell selected locations, lit sets, chose docent know if you would like to use materials from this guide or any you props and costumes, and directed his models in much the same way that design yourself during the visit. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 65–99. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 16:41 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The pleasures and pangs of Hitchcockian consumption People say, “ Why don ’ t you make more costume pictures? ” Nobody in a costume picture ever goes to the toilet. That means, it ’ s not possible to get any detail into it. People say, “ Why don ’ t you make a western? ” My answer is, I don ’ t know how much a loaf of bread costs in a western. I ’ ve never seen anybody buy chaps or being measured or buying a 10 gallon hat. This is sometimes where the drama comes from for me. 1 y 1942, Hitchcock had acquired his legendary moniker the “ Master of BSuspense. ” The nickname proved more accurate and durable than the title David O. Selznick had tried to confer on him— “ the Master of Melodrama ” — a year earlier, after Rebecca ’ s release. In a fi fty-four-feature career, he deviated only occasionally from his tried and true suspense fi lm, with the exceptions of his early British assignments, the horror fi lms Psycho and The Birds , the splendid, darkly comic The Trouble with Harry , and the romantic comedy Mr. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations.