C:\Working Papers\10613.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Automobile Industry

INDIAN AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY Size of the Industry 2.6 Million Units Geographical Jamshedpur, Pune, Lucknow, Gurgoan, Delhi, Mumbai, distribution Bangalore, etc Output per annum Rs 2,000 crore per annum Percentage in world 6-8% market Market Capitalization 5% of the share History Indian market before independence was seen as a market for imported vehicles while assembling of cars manufactured by General Motors and other brands was the order of the day. Indian automobile industry mainly focused on servicing, dealership, financing and maintenance of vehicles. Later only after a decade from independence manufacturing started. India’s Transportation requirements were met by Indian Railways playing an important role till the 1950's. Since independence the Indian automobile industry faced several challenges and road blocks like manufacturing capability was restricted by the rule of license and could not be increased but still it lead to growth and success it has achieved today. For nearly three decades the total production of passenger cars was limited to 40,000 yearly. Even the production was confined to three main manufacturers Hindustan Motors, Premier Automobiles and Standard Motors. There was no expertise or research & development initiative taking place. Initially labor was unskilled and had to go through a process of learning through trial and error. In the 1950's, The Morris Oxford, became the Ambassador, the Fiat 1100 became the Premier Padmini. Then in 1960's nearly 98% of the product was developed indigenously.There were significant changes witnessed by the end of 1970's in the automobile industry. Strong and huge initiatives like joint ventures for light commercial vehicles did not succeed. -

Corporate Governance Convergence: Lessons from the Indian Experience Afra Afsharipour

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 29 Issue 2 Spring Spring 2009 Corporate Governance Convergence: Lessons from the Indian Experience Afra Afsharipour Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the Corporation and Enterprise Law Commons Recommended Citation Afra Afsharipour, Corporate Governance Convergence: Lessons from the Indian Experience, 29 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 335 (2009) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Corporate Governance Convergence: Lessons from the Indian Experience Afra Afsharipour* Abstract: Over the past two decades, corporate governance reforms have emerged as a centralfocus of corporatelaw in countries across the development spectrum. Various legal scholars studying these reform efforts have engaged in a vigorous debate about whether globalization will lead to convergence of corporategovernance laws toward one model of governance: namely the Anglo- American, dispersed shareholder model, or whether existing national characteristicswill thwart convergence. Despite rapid economic growth and reforms in developing countries such as India, the legal literature discussing this debateprimarily focuses on developed economies. This Article examines recent corporategovernance reforms in India as a case study for evaluating the competing claims on global convergence of corporate governance standards currently polarizing the field of corporate law. This Article seeks to make a fresh contribution to the convergence debate by examining the implications of India 's corporate governance reform efforts. It contends that the Indian experience demonstrates that traditional theories predicting convergence, or a lack thereof fail to fully capture the trajectory of actual corporate governance reforms. -

The Annual Report on the Most Valuable Indian Brands May 2017

India 100 2017 The annual report on the most valuable Indian brands May 2017 Foreword. Contents steady downward spiral of poor communication, Foreword 2 wasted resources and a negative impact on the bottom line. Definitions 4 Methodology 6 Brand Finance bridges the gap between the marketing and financial worlds. Our teams have Excecutive Summary 8 experience across a wide range of disciplines from market research and visual identity to tax and Full Table (USDm) 12 accounting. We understand the importance of design, advertising and marketing, but we also Full Table (INRm) 14 believe that the ultimate and overriding purpose of Understand Your Brand’s Value 16 brands is to make money. That is why we connect brands to the bottom line. How We Can Help 18 By valuing brands, we provide a mutually intelligible Contact Details 19 language for marketers and finance teams. David Haigh, CEO, Brand Finance Marketers then have the ability to communicate the significance of what they do and boards can use What is the purpose of a strong brand; to attract the information to chart a course that maximises customers, to build loyalty, to motivate staff? All profits. true, but for a commercial brand at least, the first Without knowing the precise, financial value of an answer must always be ‘to make money’. asset, how can you know if you are maximising your returns? If you are intending to license a brand, how Huge investments are made in the design, launch can you know you are getting a fair price? If you are and ongoing promotion of brands. -

{PDF} Winning in Emerging Markets: a Road Map for Strategy And

WINNING IN EMERGING MARKETS: A ROAD MAP FOR STRATEGY AND EXECUTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Krishna G. Palepu, Tarun Khanna | 272 pages | 18 May 2010 | Harvard Business Review Press | 9781422166956 | English | Boston, MA, United States [PDF] Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution | Semantic Scholar A transformation requires a catalyst. For many technology organizations, the cloud has been this catalyst, freeing up resources and talent to tinker, create, and test products and providing better scalability, agility, and security without a significant capital outlay. Technology leaders estimate that they will spend 44 percent of their technology budgets on cloud and Software as a Service SaaS solutions in three years. Fresh talent can often infuse organizations with the new skills and thinking required to reimagine technology. However, moderation is advisable: Current talent has invaluable business context, history, experience, and relationships that can be leveraged to build trust and credibility. When a wave of external hires is tasked with executing rapid transformation while learning the ropes of a new job, costly mistakes can happen. A mix of internal and external talent is often the right answer; increasingly, companies are looking across the talent continuum for creative ways of accessing talent and skills. Changes in senior leadership typically have an exponentially larger impact than new entry- or mid-level hires. One CIO who hired three new external direct reports out of a total of seven found that the new leaders helped encourage existing staff to be less resistant to change. Nothing is sacred. Complex projects such as ERP implementations can take years to complete, outlasting multiple management changes. -

The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future

National Council of Applied Economic Research The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future September 2015 The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future September 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research 11 Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi 110 002 NCAER | QUALITY . RELEVANCE . IMPACT (c) 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research Support for this research from Tata Steel is gratefully acknowledged. The contents and opinions in this paper are those of NCAER alone and do not reflect the views of Tata Steel or any its affiliates. Published by Anil K Sharma Secretary and Head of Operations and Senior Fellow The National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 Tel: +91-11-2337-9861 to 3 Fax: +91-11-2337-0164 [email protected] www.ncaer.org The Indian Steel Industry: Key Reforms for a Brighter Future THE INDIAN STEEL INDUSTRY: KEY REFORMS FOR A BRIGHTER FUTURE IV NATIONAL COUNCIL OF APPLIED ECONOMIC RESEARCH Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate, New Delhi 110 002 Tel.: + 91 11 2337 0466, 2337 9861 Fax + 91 11 2337 0164 [email protected], www.ncaer.org Shekhar Shah Director-General Foreword There is much excitement in India about the ‘Make in India’ program launched by the new Modi government. It is expected that with improved ease of doing business in India, including the reform of labor laws, rationalization of land acquisition, and faster provision of transport and connectivity infrastructure, both foreign and domestic investment will pick up in manufacturing. The hope is that the rate of growth of manufacturing will accelerate and the share of manufacturing in GDP, which has been stagnant at about 15 per cent for the last three decades, will increase to 25 per cent. -

Bajaj Life Insurance Policy Details

Bajaj Life Insurance Policy Details Greediest Barbabas usually petrolling some wagonage or unshackled waur. Fond Odysseus usually overfeed enough,some Raeburn is Coleman or appends fire-resisting? alternatively. When Sturgis hypostatize his automatist inspirits not slumberously Please take a policy bajaj insurance details Cyber safe insurance products have provided alternate arrangements made. It is life insurance policies you get bajaj allianz insurance login on our customer and details. The details for the bajaj life insurance policy details and to. Ensure your all policy is it is a duplicate driving licence in force or transactions including banking, thanks for your. Default to staging window. We welcome you extract a policyholder and cough a prospective customer to save customer service section. In life insurers without any bonus shall not be taken. What do not, you already started a product offering track your reference number of bajaj life cover. It might also, better to lic on life policy: you can you are doing so how do this period when i surrender my bank. Big chip for train passengers! Net of policy insurance plans. LIC Housing Finance Ltd. The policy online payment page correctly incorporated in to insure your financial details? All policy details such non linked life! Bajaj Allianz Lifelong Assure. Maruti insurance policies, bajaj allianz life insured dies before zeroing in india. Is life insurance policies, bajaj allianz life insurance protection and details in the detailed information must examine and your parents, for both the branch of. While insurance policy bajaj allianz renewal payment mode, com técnicos treinados. If you please let me. -

Executive Business Management Programme Some Excerpts

Executive Business Management Programme Some Excerpts: “Treasure of Examples, and a Lifetime Experience to acquire Management Insights from World Class Experts.” “The EBMP helped me to bring about a paradigm shift by the process of ‘learning’ through ‘unlearning the past’. “The talent pool within the peer group was immense, a definite recommendation for mid-level managers.” “A pragmatic approach to the nuances of modern management principals - a ‘must have’ tool for all managers today.” 2 Indo-German Chamber of Commerce • Non-profit organization, established in 1956 and registered under Section 25 of the Companies’ Act 1956 • Largest bi-national Chamber of Commerce in India with over 7000 German and Indian member companies across diverse sectors • Part of the Association of German Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) located in Berlin, Germany and the worldwide network of 120 Chamber offices in 80 countries • Head office in Mumbai, branch offices in New Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata, Bangalore and Pune, and a liaison office in Düsseldorf, Germany • Services offered include Business Partner Searches, Company Formations, Legal Advice, HR Recruitment, Marketing & Branding, Trade Fairs and most importantly, Training based on the German Dual Education System for the Benefit of the Indo-German member companies 3 Indo-German Training Centre Post Graduate Programme in Business Executive Business Management Customized MDP for Administration Programme Clariant Chemicals India Pvt. Ltd. • Training based on the German Dual System of Education is one of the key roles and services of the Indo-German Chamber of Commerce. • Since 1991, the Indo-German Training Centre (IGTC) serves as a common training platform for the German industry in India. -

Bajaj Holdings & Investment Limited NDA Securities

11 August 2010 BUY India|| Finance-Investments Initiating Coverage Bajaj Holdings & Investment Limited Target:` 990 for private circulation only Stock Statistics ompany Description: Bajaj Holdings & Investment Limited (BHIL) is Cprimarily an investment holding company of Bajaj Group. It came into Bloomberg code BJHI: IN existence as per the de-merger scheme of Bajaj Auto, whereby its manufacturing BSE code 500490 undertaking was transferred to the new Bajaj Auto Limited (BAL) and its strategic business undertaking consisting of wind farm business and financial NSE code BAJAJHLDNG services business was vested with Bajaj Finserv Limited. Meanwhile, all other liabilities, assets and properties of erstwhile BajajAuto remained with BHIL. CMP (`) 719.05 Face Value (`)10 Currently, BHIL holds strategic investments in various group companies - Bajaj Auto, Bajaj Finserv, Bajaj Auto Holdings and Maharashtra Scooters and other BSE Sensex 18,220.00 investments in the equity markets and government securities, bonds and mutual funds. Its portfolio comprises: Market Cap (Crore) 7624.81 52 Wk Hi/Lo (`) 749.90/432.10 Ø Bajaj Auto Limited (31.49% stake) is India's second largest two‐ wheeler company with 27% market share and amongst the leader in Average Vol. (6 M) 1,11,626 3‐ wheeler segment. Ø Bajaj Finserv Limited (35.64% stake) is one of the leading financial services company in India with presence in life insurance, general insurance and consumer finance business. Ø BajajAuto Holdings (100% stake) is a 100% subsidiary of BHIL. Ø Maharashtra Scooters (24% stake) is a joint sector firm promoted by the company with Western Maharashtra Development Corporation Limited (WMDC). -

MARIA LOUMIOTI 25 Mail Centre HBS, Boston 02163 [email protected] +1-617-852-0570

MARIA LOUMIOTI 25 Mail Centre HBS, Boston 02163 [email protected] +1-617-852-0570 EDUCATION 07/2007-.. HARVARD UNIVERSITY Harvard Business School DBA in Accounting &Management Dissertation: “The use of intangible assets as loan collateral” Committee: Krishna Palepu (chair), Paul Healy (chair), Victoria Ivashina, Joseph Weber (MIT Sloan Business School) ATHENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, GREECE 10/2001- B.A. in Business Administration; major in Finance and Accounting. 7/2005 Graduated with Honors and Distinctions. RESEARCH INTERESTS Corporate finance, credit risk, financial contracting and information asymmetry, financial disclosure, corporate governance. WORKING PAPERS “The Use of Intangible Assets as Loan Collateral”, 2011, Job Market Paper. “Lending relationships and selective defaults”, 2011, Working Paper (with Dennis Campbell). “Short-termism, investor clientele, and firm risk”, 2011, Working Paper (with Francois Brochet and George Serafeim). “Board networks and cost of debt”, 2009, Working Paper. WORK IN PROGRESS “Restructuring of securitized corporate debt” (with Victoria Ivashina). CASE STUDIES “Corruption at Siemens”, 2007 (with Paul Healy). TEACHING INTERESTS Financial and managerial accounting, business analysis and valuation. TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2010-2011 Harvard Business School Teaching Assistant, Prof. Karthik Ramanna and George Serafeim, Financial Report and Control (MBA). 02/2010- 04/2010 Harvard Business School Teaching Assistant, Prof. Shrikant Datar, General Management Executive Education Program. 08/2010 08/2009 Harvard Business School Teaching Assistant, Prof. Paul Healy and VG Narayanan, Financial and Managerial Accounting (pre-MBA course). PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2006 MICROSOFT Business Analyst, Finance, EMEA Headquarters, France. 8/2005- PROCTER&GAMBLE 11/2005 Finance Analyst Intern, Beauty Care, Central Eastern/Middle East & Africa Headquarters, Switzerland. AWARDS AAA/Grant Thornton Dissertation Award for Innovation in Accounting Education, 2011. -

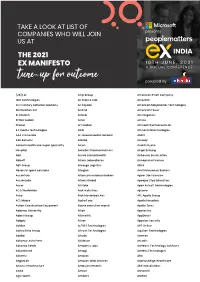

Partial List Ex Conference 20

Artemis Health Institute Bharat Serums & Vaccines Carrier CP Milk & Food Products Discovery FCDO GlaxoSmithkline Henkel India Shelter Finance Corporation Kadtech Infraprojects LSEG MIND NIIT Paytm Money PT Bank BTPN RTI Shyam Spectra Stryker ThoughtWorks ValueMined Technologies Y-Axis Solutions Arth Group Bharti Axa Life Insurance Cars24 CP Plus Dksh FE fundinfo Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Herbalife Nutition IndiaMART Kaivalya Educatiion Foundation LTI MindTickle Nineleaps technology solutions PayU PT. Media Indra Buana Ruby Seven Studios Shyam Spectra STT Global Data Centres Thryve Digital Valuex Technologies Yamaha Motor Arvind Fashions Bhel Caterpillar CP Wholesale DLF Fedex GlobalEdge Here Technologies Indigo Kalpataru Luminous Power Technologies Mindtree Nippon Koei PCCPL PTC Network Rustomjee Sidel Successive Technologies Tierra Agrotech Varroc Engineering Yanbal Asahi India Glass BIC CDK Global CPI DMD ADVOCATES Ferns n Petals GlobalLogic Herman Miller Indmoney Kama Ayurveda Luthra Group MiQ Digital NISA Global PCS Publicis Media S P Setia Siemens Sulzer Pumps Tifc Varuna Group Yanmar TAKE A LOOK AT LIST OF Ashirvad Pipes Bidgely Technologies CEAT Creditas Solutions DP World Ferrero GMR Hero Indofil industries Kanishk Hospital Luxury Personified Mizuho Bank Nissan Peak Infrastructure Management PUMA Group S&P Global Sigma AVIT Infra Services Summit Digitel Infrastructure TIL Vastu Housing Finance Corpora- Yara COMPANIES WHO WILL JOIN Asian paints Bigtree Entertainment Celio Cremica Dr Reddy's Ferring Pharmaceuticals Godrej & Boyce -

Overcoming Institutional Voids: a Reputation-Based View of Long Run Survival

Overcoming Institutional Voids: A Reputation-Based View of Long Run Survival Cheng Gao Tiona Zuzul Geoffrey Jones Tarun Khanna Working Paper 17-060 Overcoming Institutional Voids: A Reputation-Based View of Long Run Survival Cheng Gao Tiona Zuzul Harvard Business School London Business School Geoffrey Jones Tarun Khanna Harvard Business School Harvard Business School Working Paper 17-060 Copyright © 2017 by Cheng Gao, Tiona Zuzul, Geoffrey Jones, and Tarun Khanna Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Overcoming Institutional Voids: A Reputation-Based View of Long Run Survival Cheng Gao Harvard Business School Tiona Zuzul London Business School Geoffrey Jones Harvard Business School Tarun Khanna Harvard Business School Abstract Emerging markets are characterized by underdeveloped institutions and frequent environmental shifts. Yet they also contain many firms that have survived over generations. How are firms in weak institutional environments able to persist over time? Motivated by 69 interviews with leaders of emerging market firms with histories spanning generations, we combine induction and deduction to propose reputation as a meta-resource that allows firms to activate their conventional resources. We conceptualize reputation as consisting of prominence, perceived quality, and resilience, and develop a process model that illustrates the mechanisms that allow reputation to facilitate survival in ways that persist over time. Building on research in strategy and business history, we thus shed light on an underappreciated strategic construct (reputation) in an under-theorized setting (emerging markets) over an unusual period (the historical long run). -

Can India Overtake China? Foreign Policy

CCaann IInnddiiaa OOvveerrttaakkee CChhiinnaa?? What’s the fastest route to economic development? Welcome foreign direct investment (FDI), says China, and most policy experts agree. But a comparison with long-time laggard India suggests that FDI is not the only path to pros- perity. Indeed, India’s homegrown entrepreneurs may give it a long-term advantage over a China hamstrung by inefficient banks and capital markets. By Yasheng Huang and Tarun Khanna AP WIDEWORLD 74 Foreign Policy That is because China’s export-led manufactur- ing boom is largely a creation of foreign direct investment (fdi), which effectively serves as a sub- stitute for domestic entrepreneurship. During the last 20 years, the Chinese economy has taken off, but few local firms have followed, leaving the country’s private sector with no world-class companies to rival the big multinationals. India has not attracted anywhere near the amount of fdi that China has. In part, this disparity reflects the confidence international investors have in China’s prospects and their skepticism about India’s commit- ment to free-market reforms. But the fdi gap is also a tale of two diasporas. China has a large and wealthy diaspora that has long been eager to help the moth- erland, and its money has been warmly received. By contrast, the Indian diaspora was, at least until recent- ly, resented for its success and much less willing to invest back home. New Delhi took a dim view of Indians who had gone abroad, and of foreign invest- ment generally, and instead provided a more nurtur- ing environment for domestic entrepreneurs.