Exploring Development in Relation to Terrain: 3D Skeletal Analysis of the Femoral Neck-Shaft Angle by Celia Mason Bachelor of Ar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO BE DONE in BOOK} A

CLASS6 DATE: 16.05.2020 CHAPTER 2. LANDFORMS EXERCISE WITH QUESTION ANSWERS AND MAP WORK. 1. TICK THE RIGHT OPTION {TO BE DONE IN BOOK} a. Aravallis. b. Intermontane plateau. c. Faulting. d. Deposition. 2. FILL IN THE BLANKS {TO BE DONE IN BOOK} a. Pointed. b. Minerals. c. Fault zone. d. Old fold. 3. Differentiate between: {TO BE DONE IN NOTEBOOK} a. Old Fold Mountain Young Fold Mountain These mountains have been subjected to the They are newly formed and having forces of denudation for a long geological heights higher than old fold mountain. period. They are much lower with rounded peaks They have pointed peaks, steeper and and gentle slopes. deeper slopes. Eg: Aravalli in India. Eg: The Himalayas in India. b. Rift Valley Block mountain The lowland mass remaining after the The uplifted land mass remaining after faulting are known as Rift valley. the faulting are known as Block mountains It is bordered by fault zones and separated Block mountains are steep sided and flat by land masses. topped. Eg: Great Rift Valley of Africa. Eg: Vindhyas in India. c. Erosional Plains Depositional Plains This type of plains are formed as result of It is formed as a result of deposition of erosion and weathering. sediments. These plains have been flattened by the These plains are made by depositing the erosion of soil and rocks away from a soil and rocks on a lower surface. higher feature. Eg:- Upper Mississippi valley of USA. Eg:- The Indo-Gangetic Plains in India. d. Intermontane Plateaus Piedmont Plateaus They are the highest and the most extensive They are relatively low rolling hills with type. -

Mountains Block Mountains

Mountains Block Mountains • Block mountains are created when large areas or blocks of earth are broken and displaced vertically. • The uplifted blocks are termed as horsts and the lowered blocks are called graben. • Block mountains are also called fault block mountains since they are formed due to faulting as a result of tensile and compressive forces. • Block mountains are surrounded by faults on either side of rift valleys or grabens. • The Great African Rift Valley (valley floor is graben), The Rhine Valley and the Vosges mountain in Europe are examples. Compression and Tension • When the earth’s crust bends folding occurs, but when it cracks, faulting takes place. • The faulted edges are very steep, e.g. the Vosges and Black Forest of the Rhineland. • Tension may also cause the central portion to be let down between two adjacent fault blocks forming a graben or rift valley, which will have steep walls. • The East African Rift Valley system is the best example. It is 3,000 miles long, stretching from East Africa through the Red Sea to Syria. • Compressional forces set up by earth movements may produce a thrust or reverse fault and shorten the crust. A block may be raised or lowered in relation to surrounding areas. • In general large-scale block mountains and rift valleys are due to tension rather than compression. • The faults may occur in series and be further complicated by tilting and other irregularities. • Denudation through the ages modifies faulted landforms. • Block mountains may originate when the middle block moves downward and becomes a rift valley while the surrounding blocks stand higher as block mountains. -

South African Great Escarpment

Sentinel Vision EVT-227 South African Great Escarpment 19 April 2018 Sentinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 30 August 2017 from 17:17:27 to 17:18:42 UTC Sentinel-2 MSI acquired on 03 September 2017 at 08:19:59 UTC ... Se ntinel-1 CSAR IW acquired on 08 September 2017 from 16:53:05 to 16:53:30 UTC Sentinel-3 SLSTR RBT acquired from 04 January 2018 to 07:59:47 UTC Author(s): Sentinel Vision team, VisioTerra, France - [email protected] 2D Layerstack Keyword(s): Land, mountains, geology, faults, subduction, plateau, orogeny, South Africa Fig. 1 - S2 (03.09.2017) - 11,8,2 colour composite - Zoom on Cape Town region evidencing Table Mountain. 3D view 2D view Table Mountain, Sandstone layers form the ramparts overlying a basement of Precambrian slates and granite - source: Cape Town University Department of Geological Sciences of Cape Town University describes the Geology of the Cape Peninsula: "The late-Precambrian age Malmesbury Group is the oldest rock formation in the area, consisting of alternating layers of dark grey fine-grained greywacke sandstone and slate, seen along the rocky Sea Point and Bloubergstrand shorelines. These sediments were originally deposited on an ancient continental slope by submarine slumping and turbidity currents. The sequence was subsequently metamorphosed by heat and pressure and folded tightly in a NW direction so that the rock layers are now almost vertical. The Peninsula Granite is a huge batholith that was intruded into the Malmesbury Group about 630 million years ago as molten rock (magma) and crystallized deep in the earth, but has since then been exposed by prolonged erosion. -

Spatial Characteristics and Controlling Factors of the Strike-Slip Fault Zones in the Northern Slope of Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Ba

Spatial Characteristics and Controlling Factors of the Strike-slip Fault Zones in the Northern Slope of Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Basin: Insight from 3D Seismic Data Xiaoying Han 1, 2, 3, Liangjie Tang 1, 2 *, Shang Deng 4, Zicheng Cao 5 1. State Key Laboratory of Petroleum Resource and Prospecting, China University of Petroleum, Beijing 102249, China 2. Basin & Reservoir Research Center, China University of Petroleum, Beijing 102249, China 3. College of Mining Engineering, North China University of Science and Technology, Tangshan, 063009, China 4. Petroleum Exploration and Production Research Institute, SINOPEC, Beijing 100083, China 5. Exploration and Production Research Institute of Northwest Oilfield Branch Company, SINOPEC, Urumqi 830000, China *Corresponding author: Liangjie Tang E-mail address: [email protected] Telephone: +86 13701288636 Postal address: No18 Fuxue Road, Changping District, Beijing China University of Petroleum-Beijing, Beijing 102249, China Abstract: The detailed characteristics of the Paleozoic strike-slip fault zones developed in the northern slope of Tazhong uplift are closely related to hydrocarbon explorations. In this study, five major strike-slip fault zones that cut through the Cambrian-Middle Devonian units are identified, by using 3D seismic data. Each of the strike-slip fault zones is characterized by two styles of deformation, namely deeper strike-slip faults and shallower en-echelon faults. By counting the reverse separation of the horizon along the deeper faults, activity intensity on the deeper strike-slip faults in the south is stronger than that on the northern ones. The angle between the strike of the shallower en-echelon normal faults and the principal displacement zone (PDZ) below them is likely to have a tendency to decrease slightly from the south to the north, which may indicate that activity intensity on the shallower southern en-echelon faults is stronger than that on the northern ones. -

The Role of Subducting Plate Rheology in Outer-Rise Seismicity: Implications for Japan and South American Subduction Systems

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2015 The role of subducting plate rheology in outer-rise seismicity: Implications for Japan and South American subduction systems Karolina Lubecka Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Geology Commons, Geophysics and Seismology Commons, and the Tectonics and Structure Commons Recommended Citation Lubecka, Karolina, "The role of subducting plate rheology in outer-rise seismicity: Implications for Japan and South American subduction systems" (2015). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 830. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/830 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The role of subducting plate rheology in outer-rise seismicity: Implications for Japan and South American subduction systems A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Renée Crown University Honors Program at Syracuse University Karolina Lubecka Candidate for B.S. Degree and Renée Crown University Honors May 2015 Honors Capstone Project in Earth Science Capstone Project Advisor: _______________________ Dr. Robert Moucha Capstone Project Reader: _______________________ Dr. Gregory Hoke Honors Director: _______________________ Stephen Kuusisto, Director Date: May 5, 2015 i Abstract The outer rise is a subtle ridge on the seafloor located near an oceanic trench where a down-going lithospheric plate begins to bend and thus fault prior to subducting at the subduction zone. -

Earth and Plate Tectonics Online Workshop Booklet

Dynamic Earth Science The Earth and plate tectonics Workshop prepared by: Paul Baggaley, Susan Beale, Dee Edwards, Peter Kennett, Phillip Murphy, Dave Turner, Royanne Wilding Edited by: Chris King, Susie Lydon, Cally Oldershaw, Peter Kennett and Hazel Benson © The Earth Science Education Unit Copyright is waived for original material contained in this booklet if it is required for use within the laboratory or classroom. Copyright material contained herein from other publishers rests with them. Every effort has been made to locate and contact copyright holders of materials included in this document in order to obtain their permission to publish them. Please contact us if, however, you believe your copyright is being infringed: we welcome any information that will help us to update our records. If you have any difficulty with the readability of these documents, please contact the Earth Science Education Unit for further help. The Earth Science Education Unit email: [email protected] ESEU KS4 Workshops: The Earth and Plate Tectonics Contents Workshop outcomes ....................................................................................................................... 2 The Story for Teachers: Plate Tectonics ......................................................................................... 3 The big picture and the ‘facts’ of plate tectonics .............................................................................. 4 Continental Jigsaws ....................................................................................................................... -

The Youngest Fold Mountains of the World – the Himalayas

The Youngest Fold Mountains of the world – The Himalayas Millions of years ago the continents on the earth formed a single large landmass that was known Pangaea. The water body that surrounded Pangaea was called Panthalassa. When Pangaea was split first it formed two parts. The part to the north or the northern continent was known as Angaraland. The land to the south or the southern continent was termed as Gondwanaland. The sea lying between these two landmasses was known as the Sea of Tethys. The stretch of this sea was in the east-west direction. Further both these continents got divided into more parts and that is how different continents came into existence. The part of the land that had the Indian sub-continent was located in the southern hemisphere. Over the period a lot of erosion of the Angaraland and the Gondwanaland took place and the sediments got deposited on the bed of the Sea of Tethys. Slowly the Indian landmass started moving northwards towards the Eurasian landmass. The pressure on the compressed sediments deposited on the floor of the Tethys and the push of the Indian landmass resulted in folding of this material. As a result the uplifted material gave rise to different mountain ranges. These were the Himalayan ranges. The upward movement of the Indian plate continues even today which is causing an increase in the height of the Himalayas. As the Himalayas were getting formed the land between the southern peninsular plateau and the Himalayas formed a huge depression. Geologists term this depression as a geosyncline. -

THE INDIAN OCEAN the GEOLOGY of ITS BORDERING LANDS and the CONFIGURATION of ITS FLOOR by James F

0 CX) !'f) I a. <( ~ DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE INDIAN OCEAN THE GEOLOGY OF ITS BORDERING LANDS AND THE CONFIGURATION OF ITS FLOOR By James F. Pepper and Gail M. Everhart MISCELLANEOUS GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS MAP I-380 0 CX) !'f) PUBLISHED BY THE U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY I - ], WASHINGTON, D. C. a. 1963 <( :E DEPARTMEI'fr OF THE ltfrERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP J-S80 UNITED STATES OEOLOOICAL SURVEY THE lliDIAN OCEAN THE GEOLOGY OF ITS BORDERING LANDS AND THE CONFIGURATION OF ITS FLOOR By James F. Pepper and Gail M. Everhart INTRODUCTION The ocean realm, which covers more than 70percent of ancient crustal forces. The patterns of trend of the earth's surface, contains vast areas that have lines or "grain" in the shield areas are closely re scarcely been touched by exploration. The best'known lated to the ancient "ground blocks" of the continent parts of the sea floor lie close to the borders of the and ocean bottoms as outlined by Cloos (1948), who continents, where numerous soundings have been states: "It seems from early geological time the charted as an aid to navigation. Yet, within this part crust has been divided into polygonal fields or blocks of the sea floQr, which constitutes a border zone be of considerable thickness and solidarity and that this tween the toast and the ocean deeps, much more de primary division formed and orientated later move tailed information is needed about the character of ments." the topography and geology. At many places, strati graphic and structural features on the coast extend Block structures of this kind were noted by Krenke! offshore, but their relationships to the rocks of the (1925-38, fig. -

Grade 10 Geography Folding Week 5 Lesson 7

GEOGRAPHY Grade 10 Week 5 Lesson 7 FOLDING You must know: Source: • Characteristic of folds • The information on page 2 • Types of folds • Your textbook • How folding occurs • Scan the QR code or use the link • 1 What is folding? 2. Study the figure below and answer the questions by choosing the correct answer and providing a reason. 2.1 A is called the a (syncline /anticline) … Answer: Reason: 2.2 B is called the a (syncline /anticline) … Answer: Reason: 2.3 C is an (overfold/ recumbent fold) … Answer: How did it occur? 2.4 D is a (recumbent fold / overthrust fold) … Answer: How did it occur? 2.5 A stronger force can be found at E or F? Answer: Reason: You need to know from previous knowledge: Once you have completed the lesson you must • Different types of rock FOLDING be able to: Identify the different types of folds; • Plate tectonics describe how folding occur and to appreciate the • Types of plate boundaries magnitude of the Cape fold mountains. Week 4 Lesson 1 What is When tectonic forces are working and plates are pushed What are fold They are mountain ranges formed along a section of the folding? together, the rock layers are put under great pressure and get mountains? continents. In the Western Cape is the Cederberg, compressed. This pressure may make the rocks to bend into Drakenstein, Langeberg, Swartberg and Langkloof all part of folds. the Cape Fold Mountains. The highest peak- Seweweekspoortpiek is 2 325 m above sea level. Activity with Take a closed book -with a soft cover-(textbook) in two hands How are fold Fold mountains are formed when textbook and press evenly from each side. -

Mountain Formation

Mountain formation 2 Listen and read the text about mountains. Which type of mountains are formed when: a magma erupts from under the Earth? b magma pushes up under the Earth, but doesn’t erupt? c two tectonic plates push together? d water or wind cut away the land? e rock is pushed up through a crack in the Earth? The top layer of the Earth (the crust) is divided into seven large, independent sections, called tectonic plates. Below the Earth’s crust is the mantle – a layer of very hot, solid rock with some semi-molten rock called magma. Most mountains are formed by the movement of tectonic plates and rising magma. 1 Fold mountains are created when two tectonic plates collide. Their edges push together and up, causing mountains to be formed where they meet. Example: the Himalayas in Asia, the Alps in Europe Venture Level 2 . Mountain formation, p.255 © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE 2 Fault-block mountains are formed when rock is forced up a crack in the Earth’s crust. They usually have a steep front and a sloping back. Example: the Sierra Nevada Mountains in North America 3 Volcanic mountains are created when magma pushes through the Earth’s crust and erupts. The material that erupts falls on the ground and becomes solid. With each future eruption, this material gradually builds into a mountain. Example: Mount Fuji in Japan 4 Dome mountains occur when magma pushes up under the Earth’s crust without erupting. The magma then cools and hardens, leaving a dome-shaped mountain. -

Alphabetical Glossary of Geomorphology

International Association of Geomorphologists Association Internationale des Géomorphologues ALPHABETICAL GLOSSARY OF GEOMORPHOLOGY Version 1.0 Prepared for the IAG by Andrew Goudie, July 2014 Suggestions for corrections and additions should be sent to [email protected] Abime A vertical shaft in karstic (limestone) areas Ablation The wasting and removal of material from a rock surface by weathering and erosion, or more specifically from a glacier surface by melting, erosion or calving Ablation till Glacial debris deposited when a glacier melts away Abrasion The mechanical wearing down, scraping, or grinding away of a rock surface by friction, ensuing from collision between particles during their transport in wind, ice, running water, waves or gravity. It is sometimes termed corrosion Abrasion notch An elongated cliff-base hollow (typically 1-2 m high and up to 3m recessed) cut out by abrasion, usually where breaking waves are armed with rock fragments Abrasion platform A smooth, seaward-sloping surface formed by abrasion, extending across a rocky shore and often continuing below low tide level as a broad, very gently sloping surface (plain of marine erosion) formed by long-continued abrasion Abrasion ramp A smooth, seaward-sloping segment formed by abrasion on a rocky shore, usually a few meters wide, close to the cliff base Abyss Either a deep part of the ocean or a ravine or deep gorge Abyssal hill A small hill that rises from the floor of an abyssal plain. They are the most abundant geomorphic structures on the planet Earth, covering more than 30% of the ocean floors Abyssal plain An underwater plain on the deep ocean floor, usually found at depths between 3000 and 6000 m. -

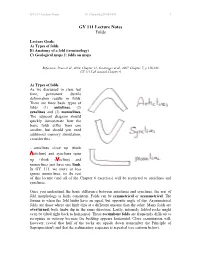

GY 111 Lecture Notes Folds

GY 111 Lecture Notes D. Haywick (2008-097) 1 GY 111 Lecture Notes Folds Lecture Goals: A) Types of folds B) Anatomy of a fold (terminology) C) Geological maps 2: folds on maps Reference: Press et al., 2004, Chapter 11; Grotzinger et al., 2007, Chapter 7; p 158-160 GY 111 Lab manual Chapter 6 A) Types of folds As we discussed in class last time, permanent ductile deformation results in folds. There are three basic types of folds (1) anticlines, (2) synclines and (3) monoclines. The adjacent diagram should quickly demonstrate how the basic folds differ from one another, but should you need additional memory stimulation, consider this… …anticlines close up (think vnticline) and synclines open up (think swncline) and monoclines just have one limb. In GY 111, we more or less ignore monoclines, so the rest of this lecture (and all of the Chapter 6 exercises) will be restricted to anticlines and synclines. Once you understand the basic difference between anticlines and synclines, the rest of fold morphology is fairly consistent. Folds can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. The former is when the fold limbs have an equal, but opposite angle of dip. Asymmetrical folds are those where one limb dips at a different amount than the other. Many folds are overturned; both limbs dip in the same direction. Lastly, intensely folded rocks might even be tilted right back to horizontal. These recumbent folds are frequently difficult to recognize in outcrop because the bedding appears horizontal. Close examination will, however, reveal that half of the rocks are upside down (remember the Principle of Superposition!) and that the sedimentary sequence is repeated (see cartoon below).