The American Archive of Public Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Connection W Will Provide Coveragethe Democraticandrepublican Will Nationalconventions

JULY 2016 Election Connection ith the Republican and Democratic National Conventions taking place this month, and the Presidential elections just a few months away, election season is in full swing. To help guide you along the election trail, we’re pleased to bring you a comprehensive schedule of news, public affairs, documentary, and digital Wprogramming from PBS and local stations. Signature series like PBS NewsHour, PBS NewsHour Weekend, and Charlie Rose, as well as our award-winning local series MetroFocus, will provide thoughtful coverage and investigative reports, news and analysis from multiple perspectives, and stories of local and national interest. One of the unique highlights of PBS Election 2016 is a partnership between PBS and NPR that allows both organizations to share news content on their respective websites. And for the first time, NPR and PBS NewsHour will join forces to report on the Democratic and Republican National Conventions. PBS NewsHour will provide coverage of the 2016 Republican National Convention (Monday, July 18 – Thursday, July 21) in Cleveland and the 2016 Democratic National Convention (Monday, July 25 – Thursday, July 28) in Philadelphia during its normal 6pm weekday timeslot. Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff will co-anchor for PBS NewsHour in partnership with NPR. On the local front, join MetroFocus hosts Rafael Pi Roman, Jenna Flanigan, and Jack Ford for convention reports, interviews with newsmakers, and timely stories on key issues affecting voters in the metropolitan region and across the country, every weeknight at 5pm. As the presidential race continues on, viewers will gain access to America’s most recognizable residence — symbol of national history and icon of democracy — Learn more at thirteen.org/Election2016 in The White House: Inside Story (Sunday July 24 at For free, online educational resources for students 9pm). -

Sonia Renee Jarvis 2 1. EDUCATION Degree Institution Field Dates J.D

Sonia Renee Jarvis 2 1. EDUCATION Degree Institution Field Dates J.D. Yale University Law 1980 B.A., Honors & Distinction Stanford University Political Science 1976 B.A. Stanford University Psychology 1976 2. FULL-TIME ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Institution Rank Field Dates Baruch College, C.U.N.Y. Visiting Professor Public Affairs 9/04-present George Washington University Research Professor Communications 9/94-6/01 Rutgers, The State University of NJ Visiting Professor Public Policy Spring 1997 & Spring 1996 Georgetown University Law Center Visiting Scholar Politics, Law & Media 9/94-6/96 Harvard University Lawrence Lombard Public Policy & Fall 1993 Visiting Professor Communications 3. PART-TIME ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Institution Rank Field Dates Catholic University Lecturer in Law Civil Rights 7/84-8/86 4. NON-ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Place of Employment Title Dates Black Leadership Forum, Wash., DC Consultant/Legal Adviser 1/01-4/07 Black Women’s Agenda, Wash., DC President 10/02-9/06 Joint Center for Political & Economic Studies Consultant 12/97-3/01 Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR) Consultant 11/97 National Coalition on Black Voter Participation Executive Director 10/87-8/94 President’s Initiative on Race, The White House Senior Consultant to the 8/97-9/99 Executive Director The Carnegie Corporation, NY Consultant 8/97 Sonia R. Jarvis, Private Practice Attorney at Law 10/86-present National Security Archive Associate General Counsel 10/86-9/87 Center for National Policy Review Managing Attorney 7/84-8/86 Citizens’ Commission on Civil Rights Project Director 7/84-8/86 Sachs, Greenbaum & Taylor Associate Attorney 10/82-6/84 Hudson, Leftwich & Davenport Associate Attorney 8/81-8/82 U. -

SPRING 2006 3 in the L NEWS

PITZER COLLEGE SPRIN G 2 0 0 6 • MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS pART I c I pANT VOLUME 4 FOR THE FOURTH CONSECUTIVE YEAR AMONG COLLEGES OUR SIZE PITZER COLLEGE FIRST TH INGS MAGA7.1Nl l <>• •'""'" "" rRILNI)\ PA R.T I C I PANT FIRST President Lauro Skondero Trombley Jenniphr Goodman '84 Wins Editor Susan Andrews Managing Editor Third Annual Alumni Award Joy Collier Designer Emily Covolconti he Third Annual Distinguished Alumni Sports Editor Award was presented Catherine Okereke '00 T during Alumni Weekend on Contributing Writers April29 at the All Class Susan Andrews Reunion Dinner. The award, Carol Brandt the highest honor bestowed Richard Chute '84 upon a graduate of Pitzer Joy Collier College, recognizes an alum Pamela David '74 na/us who has brought Tonyo Eveleth honor and distinction to the Alice Jung '0 1 College through her or his Peter Nardi outstanding achievements. Catherine Okereke '00 This year, the College hon Norma Rodriguez ored the creative energy of Shell (Zoe) Someth '83 an alumna and her many Sherri Stiles '87 achievements in film produc linus Yamane tion. Jenniphr Goodman, a 1984 graduate of Pitzer, Contributing Photographers embodies the College's com Emily Covolconti mitment to producing Phil Channing engaged, socially responsi Joy Collier ble, citizens of the world. Robert Hernandez '06 After four amazing years Alice Maple '09 at Pitzer, Jenniphr received Donald A. McFarlane her B.A. in creative writing Catherine Okereke '00 and film making in 1984. She Distinguished Alumni Award recipient Jenniphr Goodman '84 wilh Kirk Reynolds returned to her hometown in Professor of English and the History of Ideas Barry Sanders Cover Des ign Cleveland, Ohio, to teach art Emily Covolconti to preschool children after Award in 1993 at Pitzer College, to graduating. -

A Capitol Fourth Monday, July 4 at 8Pm on WOSU TV Details on Page 3 All Programs Are Subject to Change

July 2016 • wosu.org A Capitol Fourth Monday, July 4 at 8pm on WOSU TV details on page 3 All programs are subject to change. VOLUME 37 • NUMBER 7 Airfare (UPS 372670) is published except for June, July and August by: WOSU Public Media 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 614.292.9678 Copyright 2016 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. No part of this magazine may be reproduced in any form or by any means without express written permission from the publisher. Subscription is by a Columbus on the Record celebrates a Milestone. minimum contribution of $60 to WOSU Public Media, of which $3.25 is allocated to Airfare. Periodicals postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. WOSU Politics – A Landmark Summer POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Airfare, 2400 Olentangy River Road, Columbus, OH 43210 This will be a special summer of political coverage on WOSU TV. Now in its eleventh season, Columbus on the Record will celebrate its 500th episode in July. When it debuted in January, WOSU Public Media 2006, Columbus on the Record was the only local political show on Columbus broadcast TV. General Manager Tom Rieland Hosted by Emmy® award-winning moderator Mike Thompson, Columbus on the Record has Director of Marketing Meredith Hart become must-watch TV for political junkies and civic leaders around Ohio. The show, with & Communications its diverse group of panelists, provides thoughtful and balanced analysis of central Ohio’s Membership Rob Walker top stories. “The key to the show is our panelists, all of them volunteers,” says Thompson Friends of WOSU Board who serves as WOSU’s Chief Content Director for News and Public Affairs. -

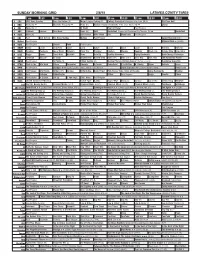

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Read the Full Year in Review for the Gwen Ifill

THE YEAR IN REVIEW ACADEMIC YEAR 2018–2019 I am proud to look back at a successful first year. Our collective task was to begin the work of building a college of media, arts, and humanities that could carry on the legacy of Gwen Ifill, a beloved alumna and American icon, while positioning ourselves to thrive in the twenty-first century. Throughout the year, we reminded ourselves of Simmons’ long history of fostering women’s independence, its strengths at the thoughtful intersection of the liberal arts and preparation for work in the world, and the great gift of a namesake who stands as a model for how we hope all graduates do good work in the world and become leaders, no matter their profession. We also had necessary conversations about the work we have to do to become the most inclusive campus. I am amazed at how much we built together: a new Mission Statement, Community Meetings, an inaugural faculty chair in Public Engagement, a Mentor-in-Residence program, two inaugural Ifill Scholarship recipients, and enhancements to student-driven media. Plus, we settled into a remodeled Communications wing and Dean’s Suite, an inspiring Gwen Ifill Exhibit and Knight Foundation Board Room, and a new home for the Children’s Literature “Book Nook.” All along, we continued so much of what already made Ifill special, from annual lectures, departmental gatherings and traditions, art exhibits, children’s literature institutes, student and faculty research, graduate colloquia, and excursions into Boston and beyond. Every morning, I have the privilege of coming to campus and passing by the Gwen Ifill exhibit where I get to witness students and others meeting her, often for the first time, and thinking about what it means to forge a life of purpose. -

Reportto the Community

REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY Public Broadcasting for Greater Washington FISCAL YEAR 2020 | JULY 1, 2019 – JUNE 30, 2020 Serving WETA reaches 1.6 million adults per week via local content platforms the Public Dear Friends, Now more than ever, WETA is a vital resource to audiences in Greater THE WETA MISSION in a Time Washington and around the nation. This year, with the onset of the Covid-19 is to produce and hours pandemic, our community and our country were in need. As the flagship 1,200 distribute content of of new national WETA programming public media station in the nation’s capital, WETA embraced its critical role, of Need responding with enormous determination and dynamism. We adapted quickly intellectual integrity to reinvent our work and how we achieve it, overcoming myriad challenges as and cultural merit using we pursued our mission of service. a broad range of media 4 billion minutes The American people deserved and expected information they could rely to reach audiences both of watch time on the PBS NewsHour on. WETA delivered a wealth of meaningful content via multiple media in our community and platforms. Amid the unfolding global crisis and roiling U.S. politics, our YouTube channel nationwide. We leverage acclaimed news and public affairs productions provided trusted reporting and essential context to the public. our collective resources to extend our impact. of weekly at-home learning Despite closures of local schools, children needed to keep learning. WETA 30 hours programs for local students delivered critical educational resources to our community. We significantly We will be true to our expanded our content offerings to provide access to a wide array of at-home values; and we respect learning assets — on air and online — in support of students, educators diversity of views, and families. -

SUNDAY – OCTOBER 9 6:00 PT / 7:00 MT: PBS NEWSHOUR DEBATES: a SPECIAL REPORT. “2016 Presidential Debate.” Watch Live Cover

SUNDAY – OCTOBER 9 6:00 PT / 7:00 MT: PBS NEWSHOUR DEBATES: A SPECIAL REPORT. “2016 Presidential Debate.” Watch live coverage (90 minutes) followed by analysis (30 minutes) co-anchored by Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff with David Brooks, Mark Shields, and Amy Walter in studio and NEWSHOUR correspondent Lisa Desjardins on location. (2 Hrs) 8:00 PT / 9:00 MT: COUNT ME IN. At a time when voter frustration is mounting, there's finally a good news story about money and voting: COUNT ME IN highlights an innovative experiment in direct democracy that gives ordinary Chicagoans direct say over local public projects and monies. Pioneered in Chicago, participatory budgeting is rapidly spreading across the country and even the White House recently made it one of its key recommendations for open government. (60 Min) 9:00 PT / 10:00 MT: FRONTLINE “The Choice 2016.” Go behind the headlines generated by Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, two of the most polarizing candidates in modern history, to investigate what has shaped them, where they came from, how they lead and why they want to be president. (2 Hrs) MONDAY – OCTOBER 10 7:00 PT / 8:00 MT: KSPS ELECTION SPECIAL “Washington 5th District Congressional Debate.” (60 Min) 8:00 PT / 9:00 MT: ANTIQUES ROADSHOW “Knoxville, Hour Three.” Highlights of this hour include a third edition of Gone With the Wind with a false inscription; signed Muhammad Ali training shoes that are appraised for $15,000 to $20,000; and a Cartier sapphire and diamond ring that was purchased at a Knoxville estate sale for less than $15, 000 and is now valued at $40,000 to $60,000. -

America in Blackblue Press Release Final (002)

*** TUNE IN ALERT FOR FRIDAY, JULY 15, 2016 *** PBS PRESENTS “AMERICA IN BLACK & BLUE: A PBS NEWSHOUR WEEKEND SPECIAL,” A TIMELY REPORT ON RACE, POLICING AND VIOLENCE THE SPECIAL REPORT WILL AIR TONIGHT – FRIDAY, JULY 15 AT 9:00 P.M. EST News Special Features Interview with White House Cabinet Secretary Broderick Johnson as well as Reports from Upcoming and Recent PBS News, Public Affairs and Documentary Programs ARLINGTON, VA; July 15, 2016 -- In response to recent events that have heightened racial tensions in the U.S., PBS presents AMERICA IN BLACK & BLUE: A PBS NEWSHOUR WEEKEND SPECIAL , a one-hour newsmagazine special report tonight at 9:00 p.m. EST (check local listings). AMERICA IN BLACK & BLUE looks at the tensions between America’s diverse communities and their local police forces, the efforts in many communities to find common ground and healing, and the delicate balance between essential law enforcement and protecting the civil and human rights of all Americans. The special preempts previously scheduled programming. After a week of violence, grief and horror, including the fatal shootings of two African American men by police officers in Minnesota and Louisiana, and five police officers killed in Dallas, AMERICA IN BLACK & BLUE will trace the roots of these events, explore the often competing accounts of responsibility and justice, and help to facilitate the conversation that Americans are having across the country about loss, fear, and whether progress on these issues can be made. Produced by WNET, AMERICA IN BLACK & BLUE will be hosted by journalist Alison Stewart, with reporting from PBS NEWSHOUR WEEKEND anchor Hari Sreenivasan, and special correspondents Chris Bury and Michael Hill. -

INDEPENDENT LENS Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University January 2021

Q2 3 INDEPENDENT LENS Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University January 2021 1 When to watch from A to Z listings for 3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – January 2021 New Mexico Colores – Sundays, 12:00 noon (except 10th, 24th) Amanpour and Company – Tuesdays–Thursdays, 11:00 p.m. New Mexico In Focus – Sundays, 11:00 a.m. (11:30 p.m. on 26th) Nova – Wednesdays, 8:00 p.m.; Saturdays, 10:00 p.m. American Woodshop – Thursdays, 11:00 a.m.; “The Impossible Flight” (2 Hrs.) – 2nd Saturdays, 6:30 a.m. (begins 2nd) “Prediction by the Numbers” – 6th, 9th America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. “Secrets in Our DNA” – 13th, 16th America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 8:00 a.m.; Tuesdays, 11:00 a.m. “Decoding da Vinci” – 20th, 23rd Antiques Roadshow – Mondays, 7:00 p.m./11:00 p.m.; “Forgotten Genius” (2 Hrs.) – 27th, 30th Mondays, 8:00 p.m. (4th only); Sundays, 7:00 a.m. Painting and Travel – Sundays, 6:00 a.m. Antiques Roadshow Recut (30 min. version) – Monday, 25th, 8:00 p.m. Paint This with Jerry Yarnell – Saturdays, 11:00 a.m. Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. P. Allen Smith’s Garden Home – Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. Austin City Limits – Saturdays, 9:00 p.m./12:00 midnight) PBS NewsHour – Weekdays, 6:00 p.m./12:00 midnight BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m. Quilt in a Day – Saturdays, 12:30 p.m. BBC World News America – Weekdays, 5:30 p.m. -

Wpsu.Org PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016

PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016 VOL. 46 NO. 2 PBS Best of Pledge Weekend... Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, February 5–7 Tune in for an entire of weekend of your favorites on WPSU, including these best-loved programs: TICKET OPPORTUNITY! Brit Floyd: Space and Time, Aging Backwards The Carpenters: Close to You Live in Amsterdam with Miranda Esmonde-White (My Music Presents) Brit Floyd pays special tribute to Pink Receive valuable insights on how to Trace the band's career, through the eyes Floyd and the era defining classic rock, combat the physical signs and of bandmates and friends, and favorites during their 2015 Space and Time tour. consequences of aging. such as "Top of the World". Friday, February 5, at 9:30 p.m. Saturday, February 6, at 3:00 p.m. Sunday, February 7, at 6:30 p.m. Make your pledge of support by calling 1-800-245-9779, or go online to wpsu.org. Democratic Presidential Ready Jet Go! Debate 2016: Advance Screening Event Saturday, February 13, at 1:00 p.m. A PBS NewsHour Special Report WPSU Studios, State College Thursday, February 11, at 9:00 p.m. The countdown has begun! Bring your little ones to WPSU for the Broadcast live from Milwaukee, Wisconsin launch of PBS Kids’ newest children’s series, Ready Jet Go! Join us just days after votes are cast in the New for an afternoon of out-of-this-world science activities, followed by Hampshire Primary and the Iowa Caucuses, interplanetary snacks and a preview screening of the first episode this will be the first time the candidates will in our television studio. -

ETV's State House Cameras Provide Worldwide Coverage As The

JULY 2015-JUNE 2016 LOCAL CONTENT AND SERVICE REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY ETV’s State House Cameras Provide Worldwide Coverage as the Confederate Battle Flag is Removed from the Capitol In the aftermath of the Charleston The fiery debate over the international newsmakers, tragedy in which nine members Confederate battle flag on the including the BBC and DW-TV, of the Emanuel AME Church were State House grounds before ETV’s and was seen as far away as gunned down during Bible study, permanent State House cameras Germany and China. South Carolina became a news also became a national broadcast, focus. carried by CNN and excerpted on Because of ETV’s commitment news services worldwide, as was to coverage of the legislature, the Gov. Nikki Haley’s press the subsequent signing of the bill. State House is covered not only by conference calling for the removal ETV cameras but by control rooms of the Confederate battle flag from The ceremony lowering the on site, which allow for coverage the State House grounds was flag, captured by ETV’s cameras, of everyday legislative events as widely covered by national news. was carried by national and well as breaking news. South Carolina ETV and SC Public Radio ETV’s educational web portal, Knowitall.org, provides a collection of free, fun, interactive sites for K-12 students, teachers, and parents. Knowitall Media became Knowitall’s new home for video, now optimized for use on tablets and mobile devices. Educators have incorporated Knowitall.org’s inquiry-based learning interactives, website teacher resources, lesson plans, simulations, image collections, and virtual field trips into their classrooms since its launch in 2000.