Palmerston North Regional Freight Hub Social Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Year Ended 31 March 2018

2008 Chairpersons Report.pub FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2018 Central Energy Trust PO Box 1242, Palmerston North 4440 32 Amesbury Street, Palmerston North 4410 Ph (06) 358 4163 Fax (06) 356 5196 www.centralenergytrust.org.nz Central Energy Trust are proud to have supported the Hilux New Zealand Rural Games. Photos to the right are from the 2018 Hilux New Zealand Rural Games. Contents Trust directory 1 Chairperson’s report 2 Statement of financial performance 9 Statement of movements in trust funds 10 Statement of financial position 11 Statement of accounting policies 12 Notes to the financial statements 14 Auditor’s report 23 Trust Directory AS AT 31 MARCH 2018 Settlors Messrs H D King and A E Gracie (Deceased) Trustees Mr R J Titcombe (Chair) MNZM, JP, GradDipBusStud appointed 1 October 2012 (Dispute Resolution), AAMINZ Mrs G M C May (Deputy Chair) Dip.Bus Studs, MBA (Dist) appointed 1 October 2009 Mr P T Askey BBS, appointed 1 October 2012 NZ Certificate in Engineering (Civil) Registered Engineering Associate Mr R J Wong BSc, CFInstD appointed 1 October 2012 FNZIFST Mr R M Karaitiana MBA, B.Arts appointed 1 October 2015 Certificate in Company Direction Accountant/Secretary Billie Stanley CA, PGDip (Prof Accounting) BDO Central (NI) Limited 32 Amesbury Street PALMERSTON NORTH Bankers ANZ Bank of New Zealand Limited Rangitikei Street PALMERSTON NORTH ASB Bank 138 The Square PALMERSTON NORTH Auditors Cotton Kelly Chartered Accountants Northcote Park Queen Street PALMERSTON NORTH Solicitors Wadham Goodman M R Wadham PO Box 345 PALMERSTON NORTH Investment Advisors Craigs Investment Partners Vero Centre 48 Shortland Street AUCKLAND 1 CENTRAL ENERGY TRUST Chairperson’s Report It is my pleasure to present the Trust’s report for the 2017-2018 year. -

Youth Directory

YOUTH DIRECTORY The Youth Directory was originally produced by the Youth One Stop Shop (‘YOSS’) in 1995. It is not a complete listing of all the agencies and organisations that work with young people in Palmerston North – but a list of community groups that we use as referral sources. On request from community groups YOSS in co-operation with START, have made this information available and it is important that it is used as a living document, needing amendments and additions. Please feel free to photocopy and hand the Youth Directory on to friends and colleagues. Please contact us with any amendments or additions that can be made in subsequent editions of the Youth Directory. Corner Andrew Young & Cuba Streets PO Box 2074, Palmerston North (06) 355 5143 [email protected] This directory was updated on 30 September 2011. CONTENTS Manawatu Lesbian and Gay Rights Association 24 Hour Help .................................5 (MALGRA) ......................................................... 13 MASH Trust ....................................................... 13 Alcoholics Anonymous .......................................... 5 MUSA Advocacy Service ...................................... 13 Al’Anon ............................................................... 5 Netsafe – The Internet Safety Group.................... 13 ARCS Manawatu Abuse and Rape Crisis Support ..... 5 New Zealand Federation of Disability Information City Doctors ........................................................ 5 Centre’s............................................................ -

Newsletter 2017 - May Volume 23 No 3 2 June 2017

Palmerston North Boys’ High School Newsletter 2017 - May Volume 23 No 3 2 June 2017 (left) RIP Jimmy Croswell. The picture above shows the farewell haka (right) ANZAC address by Denzel Chung and Finlay McRae focussed on four new WWII deaths discov- ered. (right) The school fare- wells Rob Ferreira who has gone to St John’s, Hastings (left) Five new staff gradu- ate: Mr Stevenson, Miss Belcher, Miss Close, Miss Kaandorp, Mr Braddock. Three prefects from PNBHS joined leaders from PNGHS, Awatapu and UCOL to work with the Palmerston North Youth Council to address issues in our community. Language Awards: N. Banerjee, E. Shaji, E.Kwon, S. Jiang, A. Berkahn, T. Ariyaratne, A. Keay- Graham On the initiative of Mr Finn Barnett (Old Boy Congratulations to Year 12 student Pasifika Group visit and per- and teacher at PNINS) prefects held a leader- Jacob Cranston for his back to back form at Takaro School. ship seminar with PNINS senior students. In win in Rounds 5 & 6 of the NZ Rotax picture, Mr Hamish Ruawai, new Principal and Max Challenge (Rotax Light class) in page 1 an Old Boy too Rotorua. We saw it when one of our young men stood up for a stranger who From the Rector was being verbally abused and confronted physically, by a group of Mr David Bovey young people, while trying to do his job – and our young man stood in front of the group and told them to leave. That young man made the right decision and showed real courage. Dear Parents The new term began in the worst possible way with the news that Mr Crosswell had passed away in the last week of the school holidays. -

In Liquidation)

Liquidators’ First Report on the State of Affairs of Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 8 March 2019 Contents Introduction 2 Statement of Affairs 4 Creditors 5 Proposals for Conducting the Liquidation 6 Creditors' Meeting 7 Estimated Date of Completion of Liquidation 8 Appendix A – Statement of Affairs 9 Appendix B – Schedule of known creditors 10 Appendix C – Creditor Claim Form 38 Appendix D - DIRRI 40 Liquidators First Report Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 1 Introduction David Ian Ruscoe and Malcolm Russell Moore, of Grant Thornton New Zealand Limited (Grant Thornton), were appointed joint and several Interim Liquidators of the Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) (the “Trust” or “Taratahi”) by the High Count in Wellington on 19 December 2018. Mr Ruscoe and Mr Moore were then appointed Liquidators of the Trust on 5th February 2019 at 10.50am by Order of the High Court. The Liquidators and Grant Thornton are independent of the Trust. The Liquidators’ Declaration of Independence, Relevant Relationships and Indemnities (“DIRRI”) is attached to this report as Appendix D. The Liquidators set out below our first report on the state of the affairs of the Companies as required by section 255(2)(c)(ii)(A) of the Companies Act 1993 (the “Act”). Restrictions This report has been prepared by us in accordance with and for the purpose of section 255 of the Act. It is prepared for the sole purpose of reporting on the state of affairs with respect to the Trust in liquidation and the conduct of the liquidation. -

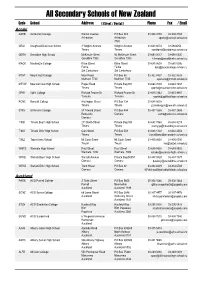

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

A 40 Year History

New Zealand Secondary Schools Athletics Association National Secondary School Cross Country Championships A 40 Year History Introduction The New Zealand Secondary Schools Athletics Association is proud to publish a forty- year history of the New Zealand Secondary Schools Cross Country Championships. Participation in the event between 1974 and 2013 totals well over 10,000 athletes from all but a handful of schools from around the country. With an annual involvement of over 1000 students it has become one of the largest secondary school sporting events in New Zealand. The idea for this document was born during the 1995 NZSSCC Championships in Masterton. At this time (before the internet), results were published in a hard copy booklet. In this particular year the first three place getters in the individual, and three and six person team categories were published for the first twenty-one years of the events history. This accompanied the full set of 1995 results. After this event, the majority of results were published electronically. Unfortunately, many of these results were lost in the mid to late nineties because there was no dedicated NZSSAA website. Sincere thanks need to be given to Don Chadderton for providing the first twenty years’ of results. Without these early results a significant part of athletics New Zealand’s history would have eventually been forgotten. These include the 1974 performance of Alison Rowe, who would later go on to win both the 1981 Boston and New York marathons. As well as Burnside High School’s 1978 performance in the junior boys event where they completed the perfect three-man score of six points. -

Manawatu Region AED Home Fields Location/Nearest AED St Matthews Collegiate Y St Matthews Collegiate St

Manawatu Region AED Home Fields Location/Nearest AED St Matthews Collegiate Y St Matthews Collegiate St. Matthew's Collegiate School - Located in the main reception of Main House (Boarding Hostel) Hokowhitu AFC Y Hokowhitu Park Hokowhitu Bowling Club, white box in a doorway on the outside of the building. Massey FC Y Massey University Rec centre desk and security van Wairarapa College Y Wairarapa College Wairarapa College Hostel which is adjacent to all the school sports fields Longburn Adventist College Y Longburn Adventist College Lonburn Adventist College - Secure Cabinet - Outside Main Reception Nga Tawa Diocesan Y Nga Tawa Diocesan A the school, in the main block in pigeon hole area staff mailings, and then on countdown wall Horowhenua College Y Horowhenua College Horowhenua College main office St Peters College Y St Peters College St Peter's College - Sick Bay PNGHS Y Hokowhitu Park Hokowhitu Bowling Club, white box in a doorway on the outside of the building. Awatapu College Y Awatapu College Awatapu College - Administration Building - Main Office Feilding High School Y Feilding High School Feilding High School Pahiatua FC Y Bush Park Multisports Complex Bush Multisports Complex on Huxley St, Pahiatua Huntley School Y Huntley School Huntley School - Staff Room Tararua College N Tararua College Bush Multisports Complex on Huxley St, Pahiatua Palmerston North Marist N Skoglund Park Freyberg Community Pool Takaro FC N Monrad Bowling club at Takaro club rooms, Z Pioneer Highway for Monrad park Freyberg High School N Freyberg High School -

How Your Child's School Is Performing

A10 The New Zealand Herald ★ Monday, April 18, 2011 NEWS nzherald.co.nz ✔ HOW YOUR CHILD’S SCHOOL IS PERFORMING Pass rates for NCEA Level 1-3 and University Entrance —measured by percentage of students participating. Pass rates for North Island schools only. THE RESULTS ARE FOR: LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 LEVEL 3 U. E. Level 1 – Year 11 Level 2 – Year 12 Upper Hutt College, Upper Hutt 75 +13 70 +1 65 +2 63 +8 Level 3 – Year 13 University Entrance - Year 13 Waiuku College, Waiuku 70 +2 76 -2 67 +9 64 N/C (Figure on the left is 2010 percentage, right next to it is how many percentage points it’s increased/decreased since 2009) ALL DECILE 7 SCHOOLS 79 +2 83 +3 77 +4 69 +2 N/A – result not available N/C – no change since 2009 * School also offers Cambridge Exams DECILE 8 ** School also offers International Baccalaureate Francis Douglas Memorial College, New Plymouth 95 +8 85 -2 88 +11 86 +14 LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 LEVEL 3 U. E. *Hamilton Boys’ High School, Hamilton 82 +8 87 +1 78 +10 73 +3 DECILE 1 Hebron Christian College, Mt Albert 83 +3 95 +3 77 -23 62 -39 Bay of Islands College, Kawakawa 62 +6 73 +17 47 -3 33 -4 *Hillcrest High School, Hamilton 84 +9 85 +12 73 +5 73 +7 Broadwood Area School, Northland 75 -6 91 +24 80 N/A 60 N/A Hutt Valley High School, Lower Hutt 75 +3 77 +8 70 +2 64 +2 De La Salle College, Mangere 74 +12 72 +3 63 +9 46 +10 Kapiti College, Kapiti Coast 89 +14 86 +6 71 +6 66 +7 Flaxmere College, Napier 71 +37 60 +23 50 +33 50 +33 Mahurangi College, Warkworth 75 +2 84 +3 78 -2 73 +2 Hukarere College, Napier 68 -20 100 +10 69 -31 69 -14 Otumoetai -

General Managers Report

SPONSORS AND OFFICIAL PARTNERS FUNDING PARTNERS Table of Contents HMI PARTNERS .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 DIRECTORY ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2017 OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 GENERAL MANAGERS REPORT .................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT MANAGERS REPORT............................................................................................................................................. 14 OPEN COMPETITION REPORT .................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 SECONDARY SCHOOL REPORT ................................................................................................................................................................................... 23 SUMMER -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

Athletic Track Bookings at 02-03-2021

Athletic Track Bookings at 02-03-2021 02/03/2021 Tuesday 4:00 PM 8:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 02/03/2021 Tuesday 4:00 PM 8:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Internal 03/03/2021 Wednesday 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 03/03/2021 Wednesday 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 04/03/2021 Thursday 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 04/03/2021 Thursday 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 04/03/2021 Thursday 6:00 PM 8:00 PM Manawatu Wanganui Masters Athletics - Clubs 05/03/2021 Friday 4:00 PM 5:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 05/03/2021 Friday 4:00 PM 6:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 06/03/2021 Saturday 10:00 AM 12:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 06/03/2021 Saturday 10:00 AM 12:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 07/03/2021 Sunday 10:00 AM 12:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 07/03/2021 Sunday 10:00 AM 12:00 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 08/03/2021 Monday 7:00 AM 4:00 PM Cornerstone Christian School - School 08/03/2021 Monday 4:00 PM 5:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 08/03/2021 Monday 4:00 PM 5:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 08/03/2021 Monday 5:30 PM 6:30 PM Special Olympics Manawatu - Other 09/03/2021 Tuesday 7:00 AM 4:00 PM Palmerston North Girls High School - School 09/03/2021 Tuesday 8:00 AM 4:00 PM Palmerston North Girls High School - School 09/03/2021 Tuesday 4:00 PM 8:30 PM Palmerston North Athletic Club - Clubs 09/03/2021 Tuesday 4:00 -

Manawatu-Whanganui Regional Sports Facility Plan Is to Provide a High Level Strategic Framework for Sport and Recreation Facility Planning Across the Region (Map 1)

MANAWATU - WHANGANUI REGIONAL SPORT FACILITY PLAN REFERENCE REPORT MARCH 2018 Foreword – Sport New Zealand Sport New Zealand aims to get more young people and adults into sport and active recreation and produce more winners on the worlds sporting stage. It does this through its strategic approach for Community Sport and High Performance Sport outcomes. Spaces, places, and facilities for sport is one of five strategic priorities in the Community Sport Strategy with a goal to develop and sustain a world leading community sport system where the need of the participant and athlete is the focus. With leadership from the network of Regional Sports Trusts, Sport NZ is actively supporting better decision making and investment for future sporting spaces and places through a collaborative regional approach with local and regional government, education, Iwi, funders, national and regional sports organisations. The drivers for taking a regional approach to facility planning can be one or more of the following: • The desire of funders to invest wisely in identified priority projects that will make the most impact • An ageing network of facilities needing refurbishment, re-purposing, replacement or removal • Changing demographics within a community, such as an increase in the population. • Changing participation trends nationally and within a region requiring new types of facilities, or a new use of an existing facility • Increasing expectations of users and user groups • A growing acknowledgement that there is a hierarchy of facilities – regional, sub-regional and local – and that regional collaboration is the only fair and reasonable way to build and manage regional and sub-regional facilities.